- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

An allergy refers to an inappropriate, exaggerated immune response against ordinarily harmless substances present in the environment.1

Anaphylaxis marks the most extreme endpoint of the spectrum of allergy. It is defined as a “serious systemic hypersensitivity reaction that is usually rapid in onset and may lead to death if not recognised and treated promptly”.2,3

Anaphylaxis has a global incidence of approximately 50-112 episodes per 100,000 person-years. The estimated lifetime prevalence is between 0.3-5.1%.2

Aetiology

Anaphylaxis is a type I hypersensitivity reaction, meaning it is mediated by IgE antibodies.4,5

On first exposure to an allergen, the individual produces IgE antibodies specific to the antigen. This does not cause symptoms of allergy. These antibodies then remain attached to receptors on basophils and mast cells.

On a subsequent exposure, binding of the antigen (the allergen) to IgE antibodies triggers basophils and mast cells to degranulate, releasing their contents, including histamine, tryptase, and chymase.

These inflammatory mediators cause vasodilation, increase vascular permeability, stimulate smooth muscle contraction and increase mucus secretion, which contributes to the clinical manifestations of anaphylaxis.

Anaphylaxis vs anaphylactoid reactions

Anaphylaxis should not be confused with anaphylactoid reaction, also called non-immunological anaphylaxis. Anaphylactoid reactions produce a similar presentation as anaphylaxis but are caused by non-IgE-mediated triggering events.4,6

Triggers for anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis can be induced by a variety of triggers including:3,7

- Food: any food could be a trigger but peanut, tree nuts and cow’s milk are the most common ones.

- Medication: antibiotics (especially penicillin), neuromuscular blocking agents, chlorhexidine

- Insect sting: particularly bees and wasps.

- Latex: found in some medical and dental supplies

- Exercise: rare (2%)

- Idiopathic: cause of anaphylaxis can remain unknown despite extensive investigations.

The most common triggers of anaphylaxis are food in children and medication in adults.

Risk factors

Some risk factors that increase the chance of anaphylaxis include:4,8

- Previous episodes of anaphylaxis: the risk of another episode in the future is approximately 1 in 12 per year

- Known allergies of any kind

- Concurrent allergic conditions such as allergic asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis (eczema)

- Regular exposure to allergens

Furthermore, the presence of the following factors can predispose an individual to develop a more severe anaphylactic reaction:9,10,11

- Advancing age

- Asthma and other chronic lung diseases

- Cardiovascular diseases

- Mast cell disease

- Previous biphasic anaphylaxis

- Individuals who take beta-blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

Clinical features

History

A key suggestive feature of anaphylaxis is the sudden onset and rapid progression of symptoms after exposure to the allergen. Typical symptoms predominately result from airway and cardiorespiratory issues:

- A feeling of the throat closing up

- Dyspnoea

- Chest tightness

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abdominal pain (especially if caused by food allergies)

If patients present late, they may be confused and obtunded because of cerebral hypoxia.

Clinical examination

Clinical features of anaphylaxis can be classified into the following, per the definition outlined by the Resuscitation Council UK.7

Airway problems

- Difficulty in breathing and/or swallowing

- Hoarse voice

- Stridor

- Swollen tongue and lips +/- saliva drooling

Breathing problems

- Dyspnoea and tachypnoea

- Wheeze (widespread)

- Cyanosis

Circulation problems

- Tachycardia, typically a rapid, weak, thready peripheral pulse

- Hypotension

- Cold, clammy skin with prolonged capillary refill time

Skin and/or mucosal changes

- Widespread urticarial/erythematous rash

- Generalised pruritus

- Angioedema

- Flushing

Differences in presentation according to the trigger

The onset and the primarily affected organ system can vary depending on the trigger of anaphylaxis:7

- Food: less rapid onset and breathing problems typically predominate

- Medication: rapid onset and circulation problems typically predominate

- Insect sting: rapid onset and circulation problems typically predominate

Differential diagnosis

The top differential diagnoses of anaphylaxis include simple allergy and other causes of sudden onset shortness of breath.

In a simple allergic reaction, skin changes like a widespread pruritic urticarial rash are often present, which can also be seen in anaphylaxis. The key differentiating factor from anaphylaxis is the absence of airway, breathing, and circulation problems.

Common causes of sudden onset shortness of breath include:3,4

- Foreign body aspiration

- Acute epiglottitis in a child

- Acute exacerbation of asthma or COPD

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pneumothorax

- Panic attack

Oral allergy syndrome is also a potential mimic of anaphylaxis. It is also a type I hypersensitivity reaction initiated by cross-reaction with a non-food allergen, such as pollen or latex, involving plant-based foods only.

Unlike anaphylaxis, it usually only causes oropharyngeal symptoms like itching and a tingling sensation, with or without mild swelling of the lips and tongue. Symptoms tend to fully resolve within one hour post-contact and rarely develop into anaphylaxis, although it is sometimes possible.

Other causes of skin rashes or cutaneous flushing should also be considered as differential diagnoses of anaphylaxis, such as:3,4

- Carcinoid syndrome

- Red neck syndrome (from rapid vancomycin infusion)

- Scombroid food poisoning (from contaminated fish)

- Monosodium glutamate poisoning

Investigations

Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening medical emergency. All patients with suspected anaphylaxis should be assessed and managed with the ABCDE approach, but some investigations may be useful. However, performing investigations should not delay the emergency management of anaphylaxis.

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Routine observations: particularly heart rate, blood pressure and pulse oximetry

- 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) to exclude potential cardiac causes or involvement

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Routine bloods: full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U&Es), CRP, liver function tests (LFTs), and coagulation can be useful if the diagnosis remains uncertain

- Arterial blood gas (ABG) if patient is hypoxic (SpO2 <94%)

- Serum mast cell tryptase level (tryptase is the major component of mast cell secretory granules)

Serum mast cell tryptase in anaphylaxis

This is recommended in all patients with suspected anaphylaxis where the diagnosis is uncertain and in children <16 years old if the cause is thought to be venom-related, drug-related, or idiopathic. However, it should never delay life-saving treatments.3,12

At least one sample should be taken within 2 hours of symptom onset and no longer than 4 hours later.3,7

Although an elevated serum mast cell tryptase level confirms the diagnosis of anaphylaxis, a normal result does not rule out anaphylaxis.

Imaging

A chest X-ray can be performed to rule out respiratory pathologies. Similar to other investigations, it should only be requested after time-critical interventions have been administered and if the diagnosis remains uncertain.4

Diagnosis

There is no single diagnostic criterion that correctly identifies anaphylaxis. A range of signs and symptoms may occur; none is entirely specific for anaphylaxis.

The Resuscitation Council UK suggests that anaphylaxis is likely when all the following three are present:7

- Sudden onset and rapid progression of symptoms

- Life-threatening airway and/or breathing and/or circulation problems

- Skin and/or mucosal changes

Additional points:2

- Diagnosis of anaphylaxis is supported by the person’s exposure to a known allergen

- Skin and/or mucosal changes alone are not a sign of anaphylaxis and can be subtle or absent in up to 20% of reactions

- Strictly speaking, if the patient does not have airway or breathing or circulation problems, that is not anaphylaxis

- Some definitions of anaphylaxis imply the need for multiple organ involvement, however symptoms can affect only one organ system

As per Resuscitation Council UK’s recommendation, give IM adrenaline and seek help if ever in doubt.7

Management

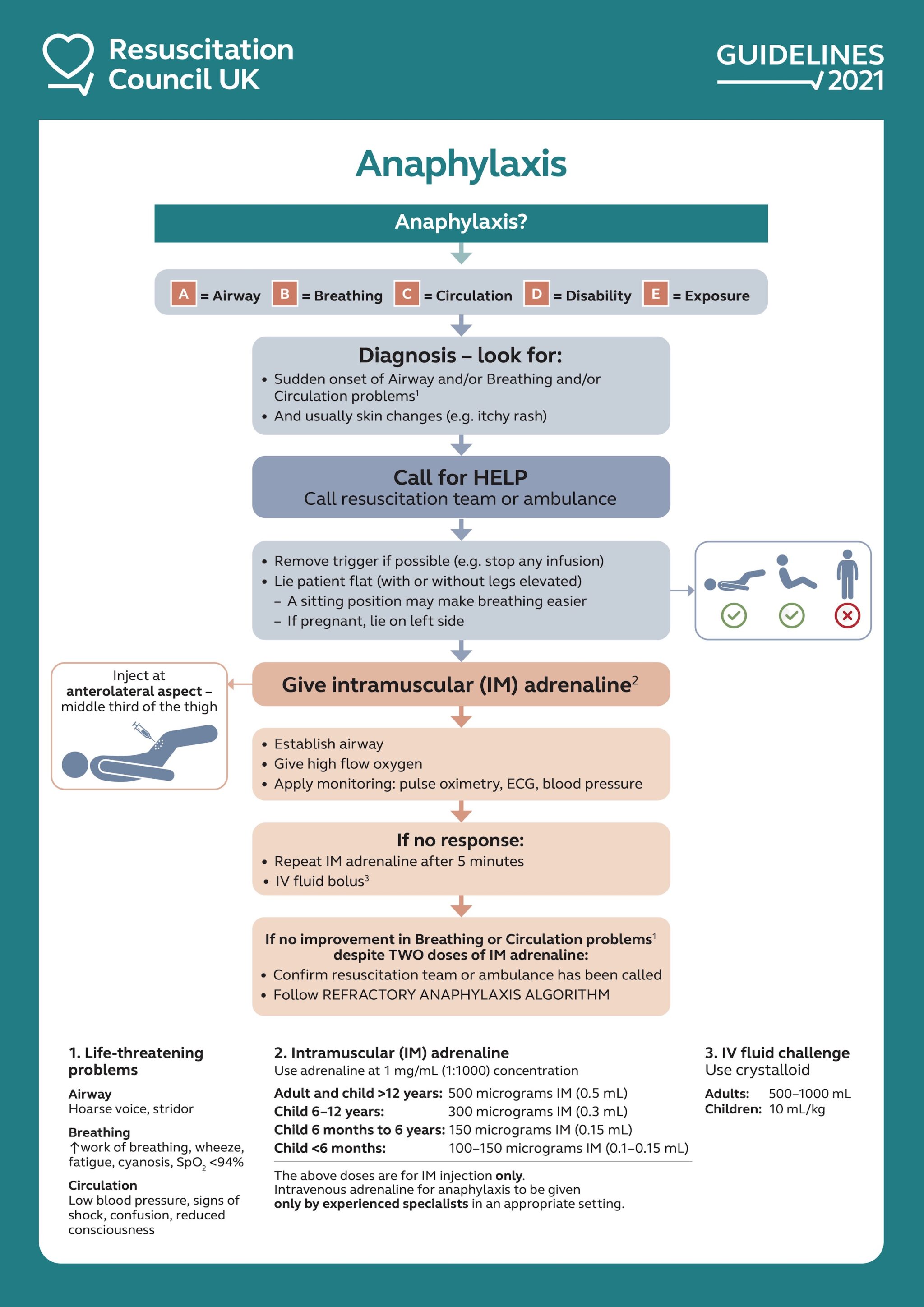

Initial emergency treatment for anaphylaxis

The patient should be assessed with an ABCDE approach, and the following should be done once anaphylaxis is suspected:7

- Call for help, involve critical care team and anaesthetists early as patients may require intubation and inotropic support

- Remove trigger if possible, e.g. stop any infusions, remove the stinger after an insect sting

- Place patient in a comfortable position: sitting position for airway and breathing problems, lying flat +/- leg elevation for circulation problems, patients must not walk or stand

The first line treatment for anaphylaxis is intramuscular (IM) adrenaline. Adrenaline is the single most important treatment; it should be given as soon as possible, and no other drug should be given preferentially to adrenaline.

If there is no response following the first IM adrenaline dose:7

- Repeat IM adrenaline after five minutes

- Give IV fluid challenge with crystalloid (adults: 500-1000 mL, children: 10 mL/kg)

Adrenaline in cardiac arrest

The dosing of adrenaline used in anaphylaxis must not be confused with the ones used in ALS (advanced life support). In ALS, 1mg (10mL) of 1:10,000 adrenaline is used instead, and it should be given via the intravenous or intraosseous route.

If there is no improvement in breathing or circulation problems despite two doses of IM adrenaline, this is refractory anaphylaxis. Subsequent management should follow a different algorithm that is described below.

Adrenaline in anaphylaxis

Adrenaline is a non-selective alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor agonist, its effect include:7

- Alpha receptor agonism mediates peripheral vasoconstriction and reduces tissue oedema

- Beta receptor agonism mediates bronchodilation, positive inotropic effects, and suppresses inflammatory mediator release

Route of administration: inject at a 90-degree angle at the anterolateral aspect of the middle-third thigh (intramuscular)

Table 1. IM adrenaline doses in anaphylaxis (Adrenaline dilution: 1:1,000 or 1 mg/mL).7

| Age | Dose |

| Adult and child > 12 years old | 500 micrograms (0.5 mL) |

| 6 years – 12 years | 300 micrograms (0.3 mL) |

| 6 months – 6 years | 150 micrograms (0.15 mL) |

| < 6 months | 100-150 micrograms (0.1-0.15 mL) |

IM vs IV adrenaline administration in anaphylaxis

The Resuscitation Council UK guidelines recommend adrenaline to be given via the IM route, even if IV access is readily available. This is due to the greater risk of adverse effects from dilution error or incorrect dosing, which could lead to tachyarrhythmias, severe hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, and even cardiac arrest7.

Only clinicians with experience in the use and titration of vasopressors, such as anaesthetists and critical care practitioners, may choose to administer adrenaline by the IV route to manage anaphylaxis.

Resuscitation Council UK

Adjunct therapy for anaphylaxis

Antihistamines

Antihistamines do not form part of the initial emergency treatment for anaphylaxis. They have no role in treating the life-threatening respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms of anaphylaxis.

Once the patient has been stabilised, non-sedating oral antihistamines can treat the skin symptoms.

Corticosteroids

Intravenous hydrocortisone was previously included in the initial management of anaphylaxis but is no longer included in the latest guidelines (2021).

The routine use of corticosteroids to treat anaphylaxis is also no longer recommended. It should only be considered after initial resuscitation for refractory reactions or ongoing asthma/shock.7

Refractory anaphylaxis

Refractory anaphylaxis refers to the persisting respiratory or cardiovascular symptoms despite two appropriate doses of IM adrenaline.7,12

Management of refractory anaphylaxis includes:7

- ABCDE approacvh

- Seek expert input early

- Maintenance adrenaline therapy with low-dose IV adrenaline infusion

- Rapid IV fluid challenge with crystalloids

IV adrenaline infusion should only be given by an experienced specialist in an appropriate setting. Before adrenaline infusion can be started or if it is deemed inappropriate to do so, IM adrenaline should be given every five minutes instead.

Anaphylaxis during pregnancy

The management of anaphylaxis in a pregnant patient is similar to that of those who are not pregnant.

The primary distinction involves the positioning of the patient to reduce compression on the inferior vena cava and abdominal aorta from the uterus:7

- Pregnant patients should always lie on their left side.

- If placed in the recovery position with normal breathing, a head-down tilt can be performed instead of leg elevation.

If >20 weeks of gestation, when the patient is placed in the supine position for airway management or to perform CPR, the uterus must be displaced manually to the left.

Cardiorespiratory arrest during anaphylaxis

If cardiorespiratory arrest happens during anaphylaxis, adrenaline should no longer be given via the intramuscular route due to impaired absorption. Additionally, attempts to give IM adrenaline may interrupt or distract the delivery of high-quality CPR.

The advanced life support (ALS) algorithm should be followed. Adrenaline should be given via the intravenous or intraosseous route and at doses as per the ALS guidelines.

Post-emergency treatment

Before discharge

For patients who received emergency treatment for suspected anaphylaxis, the following should be taken into consideration prior to being considered for discharge7,12:

- Consider keeping patients nil-by-mouth (NBM) for the first few hours following anaphylaxis due to risk deterioration and requiring intubation

- All patients with anaphylactic shock require hospital admission due to the risk of symptom recurrence

- All patients should be kept for in-hospital observation

The Resuscitation Council UK recommends a risk-stratified approach to help decide the length of in-hospital observation following anaphylaxis.

Discharge and follow-up

Before discharge, all patients should be offered the following:7,12

- Referral to a specialist allergy service

- Information about anaphylaxis, including how to recognise anaphylaxis and how to avoid the suspected trigger (if known)

- Educate on the self-management of anaphylaxis, including a prescription of 2 adrenaline auto-injectors, with appropriate training

- Information on the risk of biphasic anaphylaxis

- Information about patient support groups

Complications

Complications of anaphylaxis include:3,4,7

- Anaphylactic shock: leading cause of death

- Respiratory failure: leading cause of death

- Refractory anaphylaxis

- Biphasic anaphylaxis: recurrence of symptoms within 72 hours after complete recovery of anaphylaxis, in the absence of further exposure to the trigger

- Myocardial infarction: cardiac ischaemia may occur from hypotension associated with anaphylaxis, or from hypertension and tachycardia following adrenaline administration

- Death: usually occurs shortly after contact with the trigger

Key points

- Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening medical emergency caused by a severe systemic type I hypersensitivity reaction

- Anaphylaxis is characterised by airway and/or breathing and/or circulation problems, with or without skin and mucosal changes

- The diagnosis should be made clinically, and prompt recognition is important. If ever in doubt, give IM adrenaline and seek help from senior clinicians

- All patients should be managed using the ABCDE approach. The single most important treatment involves intramuscular injection of 1:1,000 adrenaline. (adult dose: 500 micrograms / 0.5 mL)

- Following acute management, in-hospital observation, patient education and follow up is key to avoid further episodes

Reviewer

Dr Godfrey Azzopardi

Consultant anaesthetist

Editor

Dr Jess Speller

References

- Aldakheel FM. Allergic Diseases: A Comprehensive Review on Risk Factors, Immunological Mechanisms, Link with COVID-19, Potential Treatments, and Role of Allergen Bioinformatics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021 Nov;18(22):12105.

- Cardona V, Ansotegui IJ, Ebisawa M. World Allergy Organization Anaphylaxis Guidance 2020. World Allergy Organization Journal 2020 Oct;13(10):10042.

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Angio-oedema and anaphylaxis. Revised 2022 Oct. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Anaphylaxis. Reviewed 2023 Dec; updated 2023 Jan. Available from: [LINK]

- Reber LL, Hernandez JD, Galli SJ. The pathophysiology of anaphylaxis. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2017 Aug;140(2):335-348.

- Summary statements. Definitions of anaphylaxis and anaphylactoid events. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical immunology 1998 June;101(6):481.

- Resuscitation Council UK. 2021 Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis: Guidelines for healthcare providers.

- Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan DP, Anderson HR. Burden of allergic disease in the UK: secondary analyses of national databases. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2004 Apr;34(4):520-6.

- Sampson HA. Anaphylaxis and emergency treatment. Pediatrics 2003;111(6 Pt3):1601-9

- Campbell RL, Li JTC, Nicklas RA, Sadosty AT. Emergency department diagnosis and treatment of anaphylaxis: a practice parameter. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2014 Dec;113(6):599-608.

- Kelso JM. Patient education: Anaphylaxis symptoms and diagnosis (Beyond the Basics). UpToDate. Reviewed 2023 Dec; updated 2023 Mar. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Anaphylaxis: assessment and referral after emergency treatment (Clinical guideline [CG134]). NICE 2020. Updated 202 Aug. Available from: [LINK]