- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

The inferior vena cava (IVC) is the largest vein in the body. It runs alongside the abdominal aorta, but there are several important differences between their branches and tributaries.

Overview of the inferior vena cava

The IVC is formed by the union of the right and left common iliac veins. It conveys systemic venous blood from the lower limbs and pelvis, the undersurface of the diaphragm and parts of the abdominal wall. The IVC does not drain blood from the gut.

Course of the IVC

The IVC begins in the abdomen at L5 and ends in the thorax at T8, where it enters the pericardial sac and drains directly into the right atrium of the heart.

It enters the abdomen through the caval opening of the diaphragm, which is located in its central tendon at vertebral level T8.

It is accompanied through the caval opening by the terminal branches of the right phrenic nerve.

The caval opening increases in size during inspiration, which encourages the venous return of blood to the heart through the IVC.

It is located on the posterior abdominal wall in the retroperitoneal space of the abdomen.

It descends to the right of the abdominal aorta and the vertebral column.

Because it is situated to the right of the midline, left-sided veins are longer than their equivalents coming from the right, as they have further to travel. This means that, for example, the left renal vein is longer than the right.

Anatomical relationships

Running parallel to the IVC on its left-hand side is the aorta and the cisterna chyli.

Running on its right-hand side is the right sympathetic trunk and right ureter.

Organs sitting directly in front of the IVC include the liver, duodenum and pancreas.

It is also crossed anteriorly by the portal triad within the lower free edge of the lesser omentum, the right gonadal artery, and the right common iliac artery.

Important structures passing behind the IVC include the right renal artery and the azygos vein.

Clinical relevance

The normal diameter of the IVC is 1.5 – 2.5cm – this varies depending on inspiration and expiration and also with the patient’s volume status. A diameter of <1cm indicates hypovolaemia, whereas >2.5cm suggests fluid overload.

As the central venous pressure is normally very low (5-10mmHg), IVC aneurysms are exceptionally rare. The low pressure instead makes it vulnerable to obstruction, which can be due to internal occlusion by thrombosis or spreading cancer (“tumour thrombus”), or external compression by an aortic aneurysm, intra-abdominal malignancies, or a heavily pregnant uterus.

As with the abdominal aorta, trauma to the IVC tends to be catastrophic with rapid exsanguination.

Tributaries of the inferior vena cava

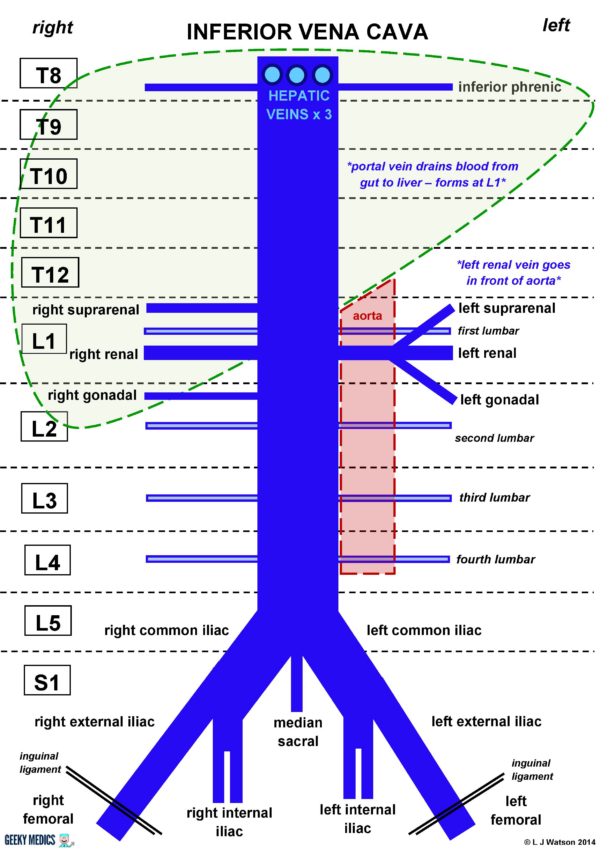

Figure 1 summarises the arrangement of the tributaries of the IVC.

The IVC has:

- Three anterior visceral tributaries (three hepatic)

- Three lateral visceral tributaries (suprarenal, renal, gonadal)

- Five lateral abdominal wall tributaries (inferior phrenic and four lumbar)

- Three veins of origin (two common iliac and the median sacral)

The IVC does not drain blood from the gut. This has to pass through the portal vein into the liver, to allow removal of any contaminants and processing of the nutrients.

The portal vein is formed by the union of the splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein behind the neck of the pancreas. It travels into the liver as part of the portal triad in the lower free edge of the lesser omentum. Once processed, venous blood passes back into the systemic circulation via the three hepatic veins.

The upper retrohepatic part of the IVC runs directly behind the liver and is firmly bound to its posterior surface by strong connective tissue attachments.

The lower part of the IVC runs parallel to the aorta on its right-hand side.

Unlike the three suprarenal arteries, there is only one suprarenal vein on each side.

Because the aorta is in the way, the left renal vein has to pass in front of it to get to the IVC. Other veins such as the left suprarenal vein and left gonadal vein also need to get across to the other side, so they join with the left renal vein and get a lift with it across the front of the aorta.

The right suprarenal vein and right gonadal vein are already on the correct side of the body, so they can drain directly into the IVC as separate tributaries.

The left renal vein is a useful landmark to find if you are given a posterior abdominal wall prosection to label. It is easy to identify, as it is the only large vein that crosses over the front of the aorta. Once you’ve found it, you have identified vertebral level L1. The coeliac artery and superior mesenteric artery will emerge from the front of the aorta above this point. The gonadal arteries will emerge just below it, and the inferior mesenteric artery will be a little further down.

The gonadal veins (testicular in men and ovarian in women) are situated surprisingly high up in the abdomen. This is because, during early fetal life, the gonads begin to develop up next to the kidneys before migrating downwards to their proper positions. They get their blood supply from where they started, not from where they end up.

The lumbar veins arise posteriorly and will not be easily visible on most anatomical prosections.

The fifth lumbar veins on either side drain into the iliolumbar vein, which is a tributary of the internal iliac vein.

Radiology

Figure 2 shows an anatomically normal IVC affected by an IVC thrombosis, you should be able to appreciate the overall arrangement of its branches and its relationships to the other structures in the retroperitoneal space.

Reviewer

Mr Avinash Sewpaul

ST8 in HPB & Transplant Surgery

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Images

- Case courtesy of Dr Ian Bickle, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 23860

References

- Larsen TR, Essad K, Jain SKA, et al; An incidental mass in the inferior vena cava discovered on echocardiogram, International Journal of Case Reports and Images 2012;3(12):58–61.

- Netter FH. Atlas of Human Anatomy, 5th Edition. Published in 2010.

- Santise G, D’Ancona G, Baglini R et al; Hybrid treatment of inferior vena cava obstruction after orthotopic heart transplantation, Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery 2010;11:817-819

Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg 2010;11:817-819 - Sinnatamby CS. Last’s Anatomy, 12th Edition. Published in 2011

- Snell RS. Clinical Anatomy by Regions, 9th Edition. Published in 2011

- Xiao L, Tong J, Shen J. Endoluminal treatment for venous vascular complications of malignant tumors, Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2012;4(2):323-328