- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Plastic surgery originates from the Greek word ‘plastikos’ meaning to mould. Plastic surgeons treat burns, skin cancers, hand trauma, congenital malformations, head and neck cancers, cleft lip and palate, aesthetic surgery and many more areas.

Plastic surgery combines three essential elements: form, function, and cosmesis.

The reconstructive ladder

The reconstructive ladder is a scheme that frames a plastic surgeon’s surgical decision making.

The ideal closure of a defect is immediate. This is only possible if the skin has sufficient laxity, the wound is not contaminated or dirty, and the resulting appearance of the skin does not disturb surrounding structures. For example, when closing a defect around the eye, care must be taken not to cause depression of the lower eyelid which can result in issues with eye closure.

If the skin cannot be closed primarily, another option is to let it heal by secondary intention. This gives sufficient time for the base of the wound to heal by granulation. If immediate closure is required (for example in a cosmetically sensitive area such as the face), then a skin graft can be utilised.

If the recipient wound bed has sufficient blood supply, a full-thickness skin graft can be utilised. This can be harvested from any region with sufficient skin laxity (e.g. supraclavicular fossa). If the blood supply is more tenuous or the defect is large, then a split-thickness skin graft can be utilised. This is typically harvested from the lateral thigh using a dermatome blade.

Grafts and flaps

Skin grafts

A graft is a section of tissue that is moved from one part of the body to another and relies on the recipient bed for its blood supply. Grafts can be further divided according to their composition or shape.

Skin grafts are commonly used for soft tissue cover following skin cancer excision or burns debridement. When the area is smaller and has a good blood supply (e.g. the face), a full-thickness skin graft is commonly utilised.

When the blood supply is not as good (e.g. the lower legs), or there is a large defect, a split-thickness skin graft is utilised.

A dermatome is used to obtain a split-thickness skin graft. This is a bladed mechanical instrument which takes a thin shaving of the skin. This includes the epidermis and a small section of the dermis.

Skin flaps

A flap is a section of tissue that is moved from one area to another and relies on its own intrinsic blood supply. If the flap is divided at its vascular pedicle and moved to a different area it is termed a ‘free flap’.

Common examples include a radial artery forearm flap, which relies on the radial artery perforating arteries for its blood supply. Flaps are typically described by shape, or by the surgeon who first described the flap.

Local flaps are utilised where the defect that requires coverage is adjacent to the flap, and the flap is simply raised and moved to cover the defect without dividing at the vascular pedicle.

If the flap is moved within the same region but is not immediately adjacent to the defect, it is termed a regional flap. If the flap is moved to a completely different area of the body, it is termed a distant flap.

A second method of classifying flaps is how the flap is moved to cover the defect. A pedicled flap is moved with the vessels remaining in place, acting as a bridge of support. An islanded flap is a type of local flap where a circular section of skin is removed with the defect, and the flap is advanced to cover the defect.

An interpolation flap is where the vascular pedicle of the flap remains intact, but the flap is advanced under or over a section of intervening skin. If the vascular pedicle is divided, it is termed a non-pedicled flap.

A type of non-pedicled flap is a free flap. This is where the vessels and other structures have been cut, and the skin is transplanted to another part of the body, and the vessels anastomosed to the vessels of the recipient area. An example includes a radial forearm free flap, where a section of skin is raised from the radial forearm, and a perforating branch of the radial artery is utilised as the blood supply.

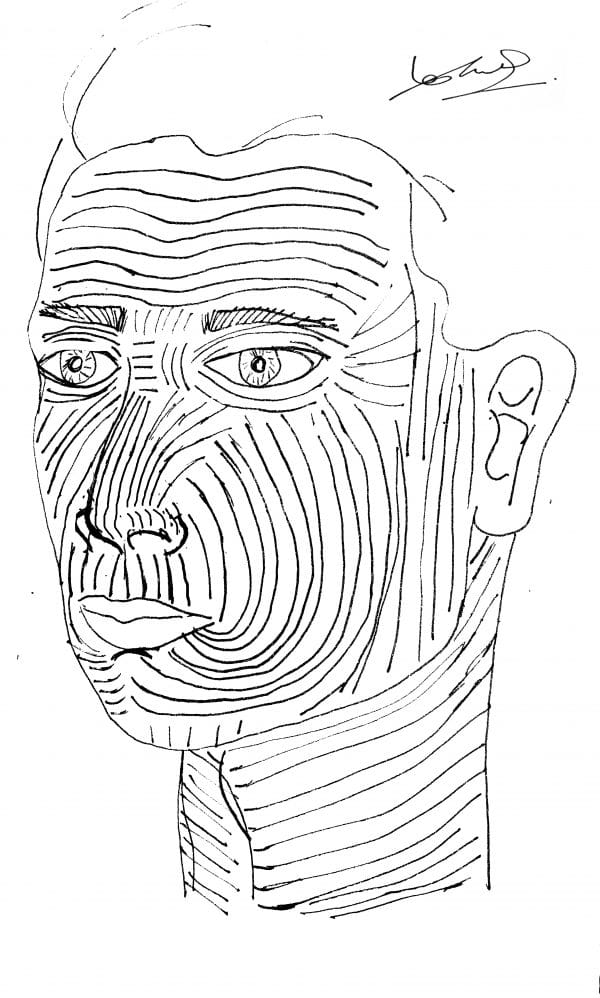

Langer’s lines are the lines across which there is the minimum amount of tension if incisions are made. It is an important surgical principle when making incisions in any part of the body, but in the context of facial surgery it is particularly important for aesthetics.

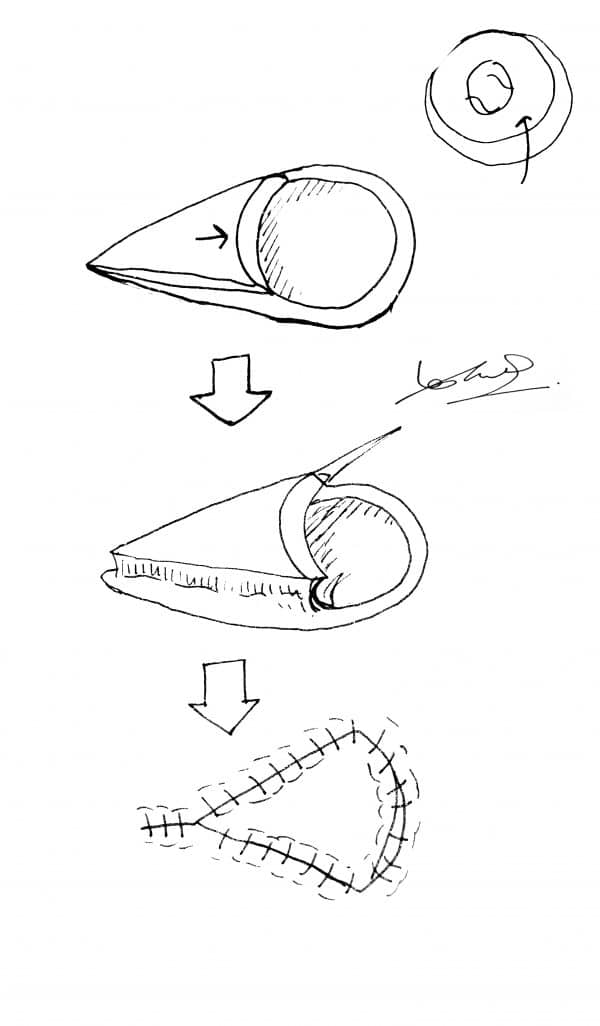

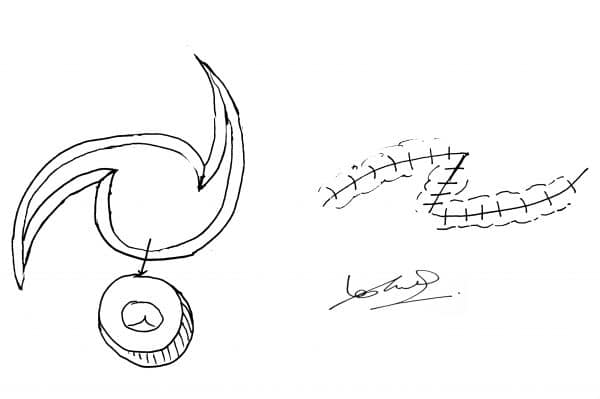

Propeller flap

This flap has this name, as the skin is twisted on its pedicle to cover a nearby region requiring the graft. The twisting of the vessels may cause clots and occlusion, however, freeing the vessels from the skin reduces this risk.

Advancement flap

This involved a simple incision of the defect, followed by the advancement of a rectangular section of skin to cover the underlying tissue. Sufficient skin laxity is paramount.

V-y advancement

This flap is where a V-shaped incision is made, with a further incision extending from the point of the V. The cuts are made, and the V-shaped area of skin is advanced into the straight incision.

Island flap

This flap is where a V-shaped incision is made, with a further incision extending from the point of the V. The cuts are made, and the V-shaped area of skin is advanced into the straight incision.

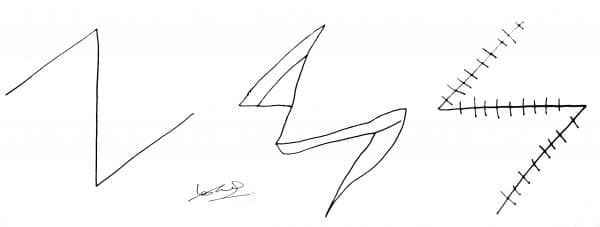

Z-plasty

A z-shaped incision is made. The angle between the lines of the z is said to be 60 degrees.

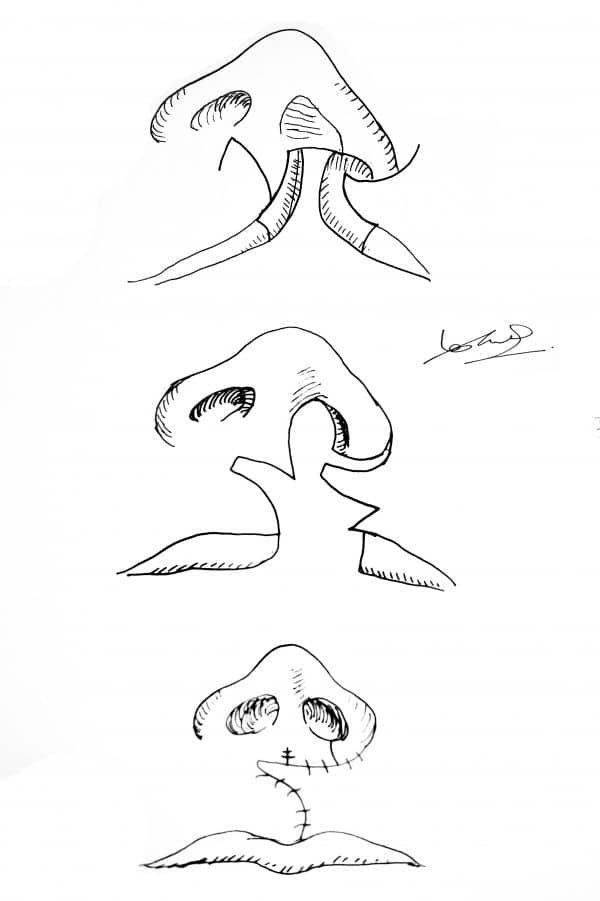

Double z-plasty with v-y advancement/jumping man

This is two z-plasties either side of a v-y advancement flap. When the incisions are made, it resembles a jumping man. This flap is commonly used in the finger web spaces and the naso-malar fold.

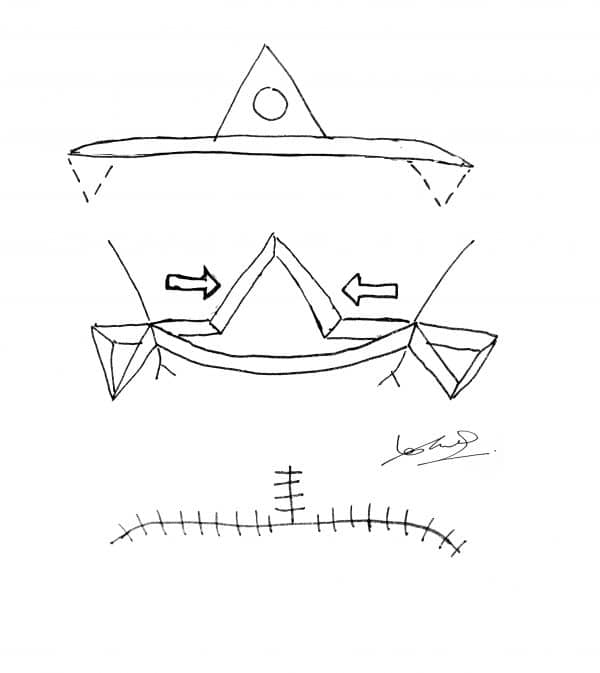

O to Z flap

The defect is excised as a circle and the wound is extended in a curved fashion at both edges. The edges are now brought together to close the defect.

Other flaps

There is a range of more complex flaps used to correct severe defects (e.g. cleft lip repair).

Burns

Classification of burns

Superficial

A superficial burn will typically result in blistering. Deroofing of these blisters will reveal pink and blanching skin underneath. The skin will be sensate and tender, with the underlying skin being shiny and wet. These burns can be managed with silver-based dressings such as urgotul, or paraffin for facial burns.

Partial-thickness

Partial-thickness burns result in damage to the superficial capillaries supplying the skin. The deeper areas will have fixed staining on palpation, and the deepest areas will be paler, and may not blanch at all. Usually, these burns will be managed conservatively with dressings (e.g. Flamazine).

Full-thickness

Full-thickness burns will commonly present as white and insensate. If the burn has extended beyond the subcutaneous fat, the skin may appear charred and shrunken. These burns will inevitably require excision, with coverage of the defect with a split-thickness skin graft. These burns will not heal with dressings.

Immediate management

Advice for the immediate management of burns:

- Apply lukewarm water under the tap for 10 – 20 minutes (NOT ice or cold water)

- Avoid application of lotions or balms

- Keep the burn clean and cover with a bandage, ideally something which does not stick to the burn (e.g. cling film)

If a patient has suffered inhalational burns, or full-thickness burns affecting >15% of the body, it is termed a ‘resus burn’.

If a patient has suffered from a severe burn, then they need to be managed using an ABCDE approach. Inhalational burns cause laryngeal oedema, so early intubation is advisable.

Other management steps for severe burns may include:

- Fluid resuscitation (see below)

- High flow oxygen

- Early debridement of dead tissue

- Escharotomy of circumferential burns

- Admission to a specialist burns intensive care unit

Calculating burn area and fluid requirements

Calculating the percentage surface area of a burn is essential. It determines the need for fluid resuscitation and can be calculated using the Mersey Burns app.

Wallace’s rule of 9s is a common method of calculating the percentage surface area of a burn:

- Arm: 9%

- Leg: 18%

- Back: 18%

- Front: 18%

- Head and neck: 9%

- Perineum: 1%

- Palm: 1%

Fluid requirements are commonly calculated using the Parkland formula:

- 4ml x burns surface area % x body weight (kg)

- Give half over the first 8 hours and half over the next 16 hours

If an adult burn exceeds 15%, or a paediatric burn exceeds 10%, then fluid resuscitation should be commenced.

Ongoing management

The key to ongoing management is to debride the burn thoroughly. All the dead tissue must be removed to avoid life-threatening sepsis. Keeping the patient warm is essential, as loss of cutaneous surface area means more fluid is lost through evaporation and hypothermia can quickly result. Patients should be cared for in a specialist burns unit.

Rehabilitation

Extubation is performed once the patient can self-respirate and maintain oxygen saturations.

Dietician input and a high-calorie diet are required to help rebuild tissues effectively.

Burn contractures must be prevented by regular physiotherapy and scar massage, and surgical release if required. Dressings are changed usually every 48 hours, and the burn is checked for signs of infection, and to ensure they are healing properly. Appropriate and early psychological support is essential.