- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a condition where an area of the abdominal aorta bulges out. This is usually asymptomatic, however, it has the potential to rupture, leading to haemorrhage and rapid death.

AAA affects more males than females, with a prevalence of 1.3% in men > 65 years in the UK.1

Aetiology

Although the exact aetiology is unknown, it is largely believed to be due to atherosclerosis. Atherosclerotic plaques are thought to compress the aortic media, leading to ischaemia and wall weakening.

Anatomy

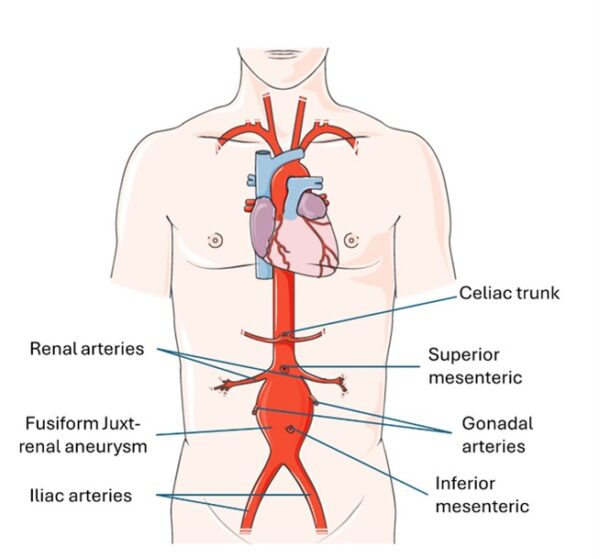

The abdominal aorta is a continuation of the descending thoracic aorta.

It supplies all of the abdominal organs, and its terminal branches supply the pelvis and lower limbs. It also supplies the undersurface of the diaphragm and parts of the abdominal wall.

The abdominal aorta begins at T12 and ends at L4, dividing into the right and left common iliac arteries.

The normal diameter of the abdominal aorta is <2cm.

Pathophysiology

Atherosclerosis causes inflammation, which leads to infiltration by macrophages and deposition of immune complexes in the aortic wall.1 There is then elastin depletion, collagen degradation and smooth muscle loss.2 This results in dilatation in all layers of the aortic wall.

AAA are in the abdominal portion of the aorta and can be juxta-renal (located within 1cm of the renal arteries), supra-renal (starting above renal arteries), and infra-renal (starting below the renal arteries). The position of the aneurysm determines the operative intervention chosen.

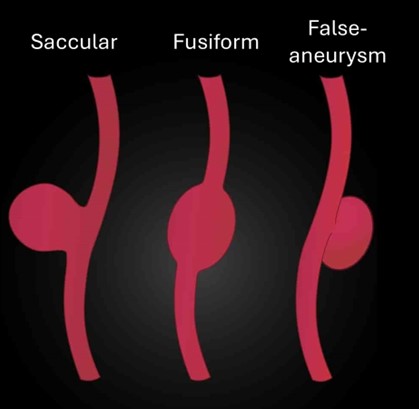

AAA can be saccular (a spherical outpouching) or, more commonly, fusiform (diffuse and circumferential dilation).

Risk factors

Risk factors for the development of an AAA include:1

- Tobacco smoking

- Family history: having a family history doubles the risk of AAA development

- Increase age

- Hyperlipidaemia

- History of atherosclerosis (including peripheral vascular disease and coronary artery disease)

- History of other aneurysms: 1 in 6 patients have additional aneurysms, and 25% of patients with AAA have an iliac aneurysm

- Hypertension: increases the risk of AAA and rupture

- COPD: associated with elastin degradation due to smoking

- History of connective tissue disorders (particularly Marfan syndrome)

- European ancestry

Males have a 4-6 times higher prevalence than women. However, women have a greater risk of AAA rupture (4-5 times increased risk).1

Diabetes appears to be a protective factor against the development of AAA.

Clinical features

History

Patients with AAA are usually asymptomatic and clinically well. Most patients are diagnosed due to screening programmes (see below) or when the AAA ruptures.

If the AAA ruptures, patients can present with rapid onset abdominal, flank, or back pain, shock, and rapid loss of consciousness (usually with cardiac arrest).1 Prompt clinical assessment and escalation to a vascular unit is critical.

If an AAA is suspected, it is important to take a full cardiovascular and surgical history. As well as including:

- Past surgical history: particularly for previous vascular and cardiothoracic/ cardiology interventions.

- Past medical history: are they known to have an AAA? Look for co-morbidities associated with AAA: hyperlipidaemia (e.g. CAD, PVD, stroke/TIA), underlying connective tissue disease, and additional aneurysms (particularly popliteal).

- Social history: particularly a smoking history, as this is the most important risk factor.

Clinical examination

It is important to complete a full peripheral vascular examination.

The most obvious sign is the presence of an expansile pulsatile central abdominal mass superior to the umbilicus. However, the absence of a mass doesn’t rule out a AAA, as palpation only has a <50% detection rate.5 It may also be normal to palpate a healthy aorta in a thin patient.

Clinical signs to look for on examination include:2

- Signs of hyperlipidaemia (e.g. xanthelasma, corneal arcus)

- Abdominal scars (e.g. midline laparotomy scars as this could make open surgery harder due to the presence of adhesions and could indicate previous aortic surgery, including aorto-femoral bypass).

- Features of Marfan syndrome (e.g. high arch palate, tall stature, arachnodactyly).

- Previous cardiac or vascular surgical scars: midline thoracotomy scar (e.g. for CABG), vertical groin scars (femoral endarterectomy or proximal exposure for femoral-popliteal/ distal bypass), medial thigh and calf wounds (venous harvest scar).

- Renal bruits on auscultation

- Abdominal distension: for signs of rupture.

- Grey Turner’s sign: retroperitoneal haemorrhage indicating rupture.

- Signs of hypovolaemic shock: pallor, loss of consciousness, prolonged CRT, and hypotension.

Differential diagnoses

Other pathologies can mimic a ruptured AAA; therefore, it must be ruled out before considering other diagnoses. These can include:

- Diverticulitis

- Renal colic

- Biliary colic

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Spinal disc prolapse

- Appendicitis

- Ovarian torsion

- Gastrointestinal haemorrhage

- Bowel obstruction

- Mesenteric artery occlusion

Investigations

AAA screening

AAA is usually diagnosed by a screening ultrasound. It is defined as abdominal aortic dilation of >1.5 times the expected anterior-posterior diameter, this is usually >3cm.1

All men over 65 are invited to AAA screening:1

- If the AAA is ≥5.5 cm, they should be seen by a vascular specialist within 2 weeks

- If the AAA is <5.5cm, they should continue surveillance by the screening programme

Other investigations

Other relevant investigations include:1

- Ultrasound for surveillance of asymptomatic AAA and following endovascular surgery (note – ultrasound cannot exclude a ruptured AAA)

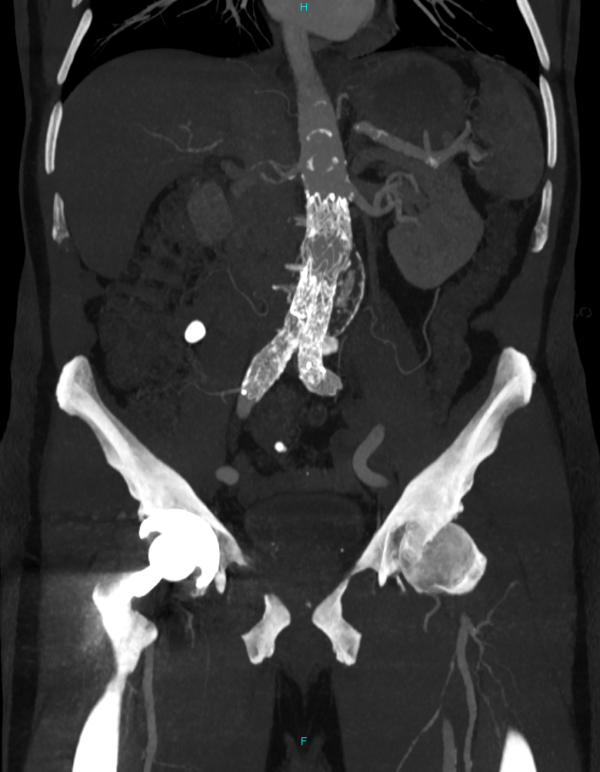

- Contrast-enhanced CT angiography: used to confirm rupture AAA and for operative planning to assess anatomy and suitability for open and endovascular surgery in elective and emergency surgery)

- Pre-operative blood tests, including full blood count, crossmatch and electrolytes

- Pre-operative ECG

Management (asymptomatic AAA)

Management of an asymptomatic AAA is dependent on the aneurysm size on ultrasound and the fitness of the patient.

Conservative management

If the aneurysm is < 5.5cm, conservative management and surveillance is indicated:1

- Lifestyle advice: including referral to stop smoking services

- Antiplatelet therapy: aspirin 75mg OD

- Statins

- Appropriate anti-hypertensives if BP >140mmHg

Surveillance

- Annually for AAA 3.0-4.4cm.

- Every 3 months for aneurysms 4.5-5.4cm.

Surgical management

If the aneurysm is ≥5.5cm in diameter or >4cm and rapidly growing (>1cm per year), the patient will need an elective surgical repair.1

General principles of surgical management include:

- Antibiotic prophylaxis

- VTE prophylaxis: LMWH the evening following surgery.

- Open aortic repair or endovascular aortic repair (EVAR).

- Open repairs have an arterial line, central venous line, epidural, and urinary catheter, and most have an NG tube inserted in the anaesthetic room

Patients undergoing elective AAA surgery require 2 units of RBC cross-matched and cell salvage.

EVAR

EVAR is considered for patients with more co-morbidities, women of any age, and men >70 years. This is due to the lower perioperative morality and decreased length of hospital stay.6

However, EVAR is prone to more longer-term complications than open repair and so needs long-term post-surgical surveillance. EVAR has a 48% risk of graft-related complications.7

If the AAA is juxta-renal or supra-renal, or if the anatomy is too complex for standard EVAR, a fenestrated EVAR is used. Fenestrated EVAR allows blood flow to the renal arteries and other branching arteries (coeliac and superior mesenteric artery).1

EVAR is performed by inserting a stent graft through the femoral arteries under radiological guidance. The stent allows the blood to be diverted through the graft instead of the aneurysm sac.

Following EVAR, imaging is recommended at one, six and twelve months to check on the graft and any endoleaks (where blood flows outside the stent-graft and around it in the aneurysm sac).8 Annual ultrasound is recommended following this. Endoleaks are an important complication following EVAR.

Table 1. The classification and management of endoleaks.

| Endoleak | Description | Management |

| Type 1 | Blood is flowing into the aneurysm sac due to an incomplete seal between the stent and the aneurysm neck from above or below. This puts pressure on the walls of the aneurysm, increasing the risk of rupture. | Open or endovascular surgical repair. |

| Type 2 | Blood is back-bleeding into the aneurysm sac from branch arteries (inferior mesenteric artery and lumbar arteries). This is less dangerous than type 1 as it is under low pressure. | Monitor with regular scans (usually CTA) and consider intervention if the AAA is expanding. |

| Type 3 | Blood is flowing into the sac due to defects in the graft material or the seal between graft components. This is high pressure and dangerous. | Open or endovascular surgical repair. |

| Type 4 | Blood flowing into the sac through the stent–graft fabric pores. This stops once a patient’s post-operative coagulation status returns to normal. | Usually self-resolves. |

| Type 5 | AAA expansion with no radiographic sign of a leak site. | Consider further investigation. |

Open aortic repair

Open surgery is preferred in healthier patients and men <70yrs. This is because grafting in open surgery lasts longer and has more up-front risks than EVAR.

Open repair is done via a laparotomy incision. The aorta is clamped, the aneurysm is opened, and back-bleeding branch arteries are ligated. A graft is sutured in, and the remaining aneurysm sack is closed over the top.11

Management (ruptured AAA)

Ruptured AAA is a surgical emergency and must be considered for anyone with abdominal/back pain and signs of shock. It is more likely if they have an existing AAA, are >60 years old, have a history of smoking, or hypertension.8

Assessment and investigations

Patients with a suspected AAA require:

- ABCDE assessment and urgent senior clinical review

- Bedside aortic ultrasound

- Blood tests: cross match, coagulation profile, FBC (may show anaemia unless the bleeding is tamponaded by retroperitoneum)

CT angiography (CTA) is the definitive imaging modality for ruptured AAA. It would show retroperitoneal haematoma and contrast extravasation.1 This helps with operative planning as a stable patient with ruptured AAA has a better chance of survival to discharge with local anaesthetic EVAR compared to open surgery.

Seeking a definitive diagnosis by CTA shouldn’t delay the treatment of unstable patients. Patients should be assessed, scanned, and transferred to theatre within 30 minutes.20

Management

Immediate management of a ruptured AAA should include:1

- IV access (and limited fluid resuscitation)

- Analgesia

- Antibiotic prophylaxis

- Major haemorrhage protocol activation where appropriate.

- Blood transfusion if Hb <100 g/L with intraoperative bleeding

It is key to not over-correct the BP as this could exacerbate the rupture. BP should be managed to aim for a target systolic blood pressure of 70-90mmHg (this is called permissive hypotension).21

The definitive treatment is an urgent surgical repair by either EVAR or open aortic repair (with the same reasons for surgery choice as above).

Complications

Ruptured AAA

Abdominal compartment syndrome can occur following rupture repair. This is where the intra-aortic pressure exceeds 20mmHg, leading to organ failure.22 This requires a laparostomy and delayed closure.

There is an 80% mortality rate from ruptured AAA.2 Surgical repair of ruptured AAA has a 35-37% mortality rate.23

Postoperative complications

Early

Early postoperative complications include:12,13,14

- Postoperative ileus: a common complication following open surgery due to having a laparotomy and usually resolves within a few days.

- Acute kidney injury (AKI): EVAR patients have iodinated contrast, and so patients (especially those with CKD) are at risk of developing contrast-induced nephrotoxicity. Patients undergoing open repair requiring a supra-renal clamp are also at risk of AKI and long-term renal replacement therapy.

- Bowel ischaemia can occur following AAA surgery, and patients often present with bloody diarrhoea, worsening lactate, and inflammatory markers in the first few days following surgery. This necessitates surgical resection in approximately 2% of patients.

- Spinal cord ischaemia: a rare complication in EVAR and open surgery caused by lack of blood flow to the spinal cord from aortic branch arteries. It is more common in complex endovascular repairs (e.g. fenestrated EVAR) and is proportionate to the stent-graft coverage of the aorta.

- Pseudoaneurysms (false aneurysms): extravasation of blood but only involving outer connective tissue, more common in EVAR following common femoral artery puncture.

- Distal embolisation: 5% incidence resulting in acute limb ischaemia. This can occur due to distal embolisation peri- or post-operatively following surgery.

- Retrograde ejaculation occurs in up to 30% patients following open surgery

Open surgery also has risks of chest infection, respiratory failure, and MI. The mortality rate in the UK is 0.4% for EVAR and 3.0% for open AAA repair.

Late

Late postoperative complications include:15,16,17,18

- Aortic neck dilation: occurs in approximately 25% of patients following EVAR

- Graft infection: can lead to aorto-enteric fistula (approximately 1% in open repair)

- Graft occlusion: particularly in the graft limb. Approximately 3% risk in open repair over 10 years and 7% in EVAR

- Endoleak (see Table 1): 24% risk following EVAR, resulting in an approximately 10% reintervention rate per year

- Incisional hernia

- Abdominal adhesions

Prognosis

Most AAA usually grow at a rate of 0.2-0.3cm per year.2 The risk of AAA rupture for aneurysms >5.5 cm is approximately 5% per year.19 However, the rupture risk depends on the size.

Key points

- AAA is a surgical condition where part of the abdominal aorta bulges out and forms an outpouching.

- AAA is thought to occur due to atherosclerosis, however, may factors can affect development.

- Smoking, hyperlipidaemia and increasing age are the main risk factors associated with AAA development.

- Men have a higher prevalence of AAA, but women have a greater risk of AAA rupture.

- AAA are usually asymptomatic and commonly present following routine screening of men >65 years.

- AAA can be managed conservatively or surgically depending on the size and expansion rate of the aneurysm.

- Indications for endovascular or open aortic repair are dependent on the clinical anatomy and patients’ risk factors.

- AAA operations have many complications including ileus, AKI, graft infection, graft occlusion, and endoleaks following EVAR.

- AAA rupture is a surgical emergency, which carries a high mortality rate. It should be considered in patients presenting with back or abdominal pain and signs of shock.

- AAA rupture needs careful BP management and urgent surgery within 30 minutes of presentation.

Reviewer

Mr Philip Bennett

Consultant vascular surgeon

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- McMahon G. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. BMJ best practice. 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Knott L. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Patient.info. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Laboratoires Servier. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Adapted by Geeky medics. Licence: [CC BY-SA 3.0]

- Hapugoda S. A saccular aneurysm (left), a fusiform aneurysm (middle) and a pseudoaneurysm (right). Radiopaedia. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Licence: [CC BY NC SA 3.0]

- Wanhainen A, Verzini F, Van Herzeele I, et al. Editor’s choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 clinical practice guidelines on the management of abdominal aorto-iliac artery aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019 Jan;57(1):8-93.

- Endovascular versus Open Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(20):1863-71.

- Endovascular Repair of Aortic Aneurysm in Patients Physically Ineligible for Open Repair. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(20):1872-80.

- NICE. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: diagnosis and management. NICE. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Bennett P. Angiography showing an EVAR using a Medtronic graft (Suprarenal fixation). 2024. Image provided courtesy of P Bennett.

- Bennett P. CT showing an EVAR using a Gore graft (Infrarenal fixation). 2024. Image provided courtesy of P Bennett.

- McMonagle M, Stephenson. Vascular and Endovascular Surgery at a Glance. Wiley. 2023.

- Baxter BT, McGee GS, Flinn WR, et al. Distal embolization as a presenting symptom of aortic aneurysms. Am J Surg. 1990 Aug;160(2):197-201.

- Tennant J, Wright J. Patient Information Leaflet for: Recovery from Open Surgery for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. 2020. Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

- Waton S, Johal A, Li Q, Atkins E, Cromwell DA, Williams R, Harkin DW, Pherwani AD. National Vascular Registry: 2023 State of the Nation Report. London: The Royal College of Surgeons of England, November 2023.

- Kouvelos GN, Oikonomou K, Antoniou GA, et al. A systematic review of proximal neck dilatation after endovascular repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Endovasc Ther. 2017 Feb;24(1):59-67

- Hallett JW Jr, Marshall DM, Petterson TM, et al. Graft-related complications after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: reassurance from a 36-year population-based experience. J Vasc Surg. 1997 Feb;25(2):277-84.

- Cochennec F, Becquemin JP, Desgranges P, et al. Limb graft occlusion following EVAR: clinical pattern, outcomes and predictive factors of occurrence. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007 Jul;34(1):59-65.

- Schurink GW, Aarts NJ, vanBockel JH. Endoleak after stent-graft treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. Br J Surg. 1999 May;86(5):581-7.

- Parkinson F, Ferguson S, Lewis P, Williams IM, Twine CP. Rupture rates of untreated large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients unfit for elective repair. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2015;61(6):1606-12.

- Vascular Society. Diseases of the Aorta. All you need to know about Vascular surgery. Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Wanhainen A, Verzini F, Van Herzeele I, et al. Editor’s choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 clinical practice guidelines on the management of abdominal aorto-iliac artery aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019 Jan;57(1):8-93.

- Cripps MW, Perumean JC. Abdominal compartment syndrome. BMJ best practice. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Investigators It. Endovascular or open repair strategy for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: 30 day outcomes from IMPROVE randomised trial. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2014;348:f7661.