- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a progressive loss of central vision associated with the formation of drusen and changes in the retinal pigmentary epithelium.1, 2 As the name suggests, it is primarily associated with ageing.1-3 AMD is the most common cause of blindness in people over the age of 60 in the UK and Ireland.2

Aetiology and risk factors

There is no clear, defined cause of AMD. Instead, there is a multitude of lifestyle and environmental factors that contribute to the development of the disease in susceptible individuals.1-3

Risk factors include:

- Age

- Ethnicity (more common in Caucasian individuals)

- Family history

- Smoking

- Hypertension

- Diet (high fat intake)

- Drugs (e.g. aspirin)

- Other (sunlight exposure, blue eyes, female>male, previous cataract surgery)

Classification

For non-specialists, AMD is classified broadly into two different clinical presentations – “dry” or “wet” AMD. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) classification is a staging system that is useful for directing management in specialist care. This is described in Table 1.

Table 1. AREDS Classification of AMD 5

| Type of AMD | Clinical features |

| No AMD

|

|

| Early AMD

|

or

or

|

| Intermediate AMD

|

or

or

|

| Advanced AMD

|

or

|

Dry AMD

Dry AMD represents approximately 90% of all AMD.1,2 It is non-exudative and non-neovascular (therefore “dry”). This phase of AMD is characterised by the presence of asymptomatic drusen formation in Bruch’s membrane. Drusen are small yellowish deposits which are visible on fundoscopy (Figures 1 and 2). Small numbers (roughly <5) of drusen measuring <63μm are considered a normal sign of ageing.

As AMD progresses, other pathological changes, including pigmentary changes in the retinal pigmentary epithelium (RPE) and geographic atrophy (Figure 3) develop. When occurring at the fovea, this is indicative of advanced AMD and often significant visual loss.

Visual deterioration during dry AMD is usually slow (occurring over many years), but progresses as the number and size of the drusen increase. The end result can be advanced AMD (that is, either geographic atrophy or wet AMD) and blindness. However, even in later stages, it is important to note that the appearance of the retina does not always correlate with measured visual acuity.1-3

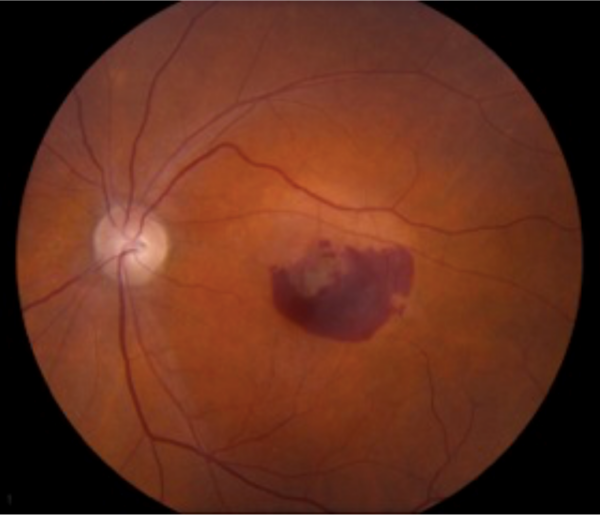

Wet/neovascular AMD

Wet AMD is characterized by the formation of a choroidal neovascular membrane made up of new, aberrant blood vessels underneath the retina (Figure 4). This is driven by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a growth hormone that promotes angiogenesis and neovascularisation. This results in a more rapidly progressive loss of vision, either by exudate from the new, leaky vessels or by haemorrhage.

Clinical features

History

Patients most commonly complain of progressive, central visual loss. They may have noticed this as difficulty in making out images due to loss of contrast in vision, an inability to recognise faces or difficulty when reading.

Additional typical symptoms of AMD include:

- Area of vision affected (AMD classically on affects central vision)

- Onset and duration of symptoms (if very acute then more likely to be wet AMD and is an ocular emergency)

- Symptom variation throughout the day (AMD symptoms are often exacerbated by low light conditions)

- Associated symptoms such as eye pain, visual disturbances around lights, flashes and floaters (if any of these are present, consider alternative diagnoses)

- Check if the patient’s visual loss is experienced in one or both eyes (AMD can affect both, although it may be asymmetrical in its distribution)

- Rapid onset of symptoms, or rapid visual deterioration in a patient with known AMD, is associated with wet AMD. This requires urgent ophthalmological review for sight-saving therapy.

- ± associated risk factors (above)

- No other pre-existing conditions making other forms of visual loss more likely (e.g. diabetes, diabetic retinopathy/macular oedema)

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Hypertension

- Cardiovascular disease

- Previous cataract surgery

- Conditions that may make other causes of visual loss a more likely explanation for their symptoms – for example, diabetes and diabetic retinopathy

- Aspirin use may be associated with an increased risk of AMD

- Check what antihypertensive agents the patient is on (if any) and their adherence, as you may need to alter these

- Family with AMD increases risk

- Smoking status

- Diet

- Impact on activities of daily living – think about what aids you might be able to offer your patient

- Driving status

- Falls risk assessment may be appropriate

Clinical examination

A thorough fundoscopy and eye examination should be performed. Please see the Geeky Medics guide here.

Common examination findings include:

- Visual field assessment – central scotoma (loss of the central vision)

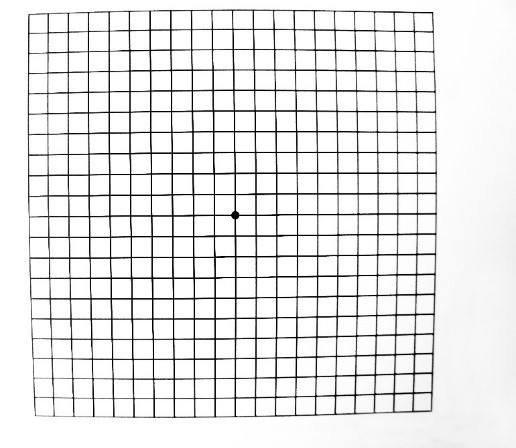

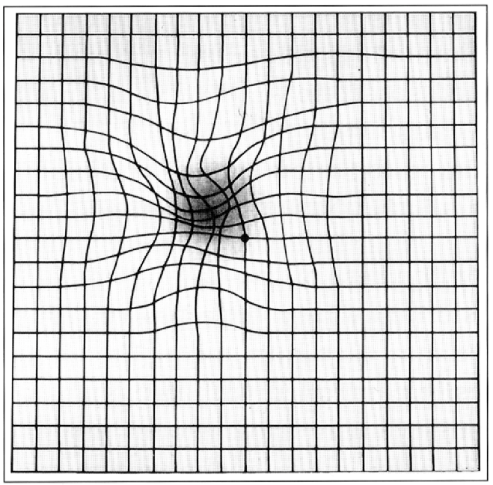

- Amsler grid – central metamorphopsia (loss of linearity in the grid centrally, Figures 5 and 6)

- Fundoscopy, using a hand-held ophthalmoscope/slit lamp – visualisation of drusen/choroidal neovascular membrane/geographic atrophy

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for AMD depends on whether the loss of vision is sudden, as in wet AMD, or gradual, as in dry. The most common differentials and their classical differentiating features are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2. Common differentials for a gradual loss of vision

| Differential diagnosis | Features |

| Dry AMD |

|

| Open-angle glaucoma |

|

| Cataract |

|

| Diabetic retinopathy |

|

Table 3. Common differentials for sudden, painless loss of vision

| Differential diagnosis | Features |

| Wet AMD |

|

| Retinal detachment |

|

| Central retinal artery occlusion |

|

| Giant cell (temporal) arteritis |

|

| Vitreous haemorrhage |

|

| Retinal vein occlusion |

|

Investigations

To date, there are no reliable biological markers useful in the assessment of AMD.1-3 In the community/non-specialist setting, patients are identified clinically with good history taking, visual field exam and fundoscopy. Amsler grid testing is useful in picking up altered central vision. Imaging in a specialist centre, however, is the gold-standard for investigation.1,2

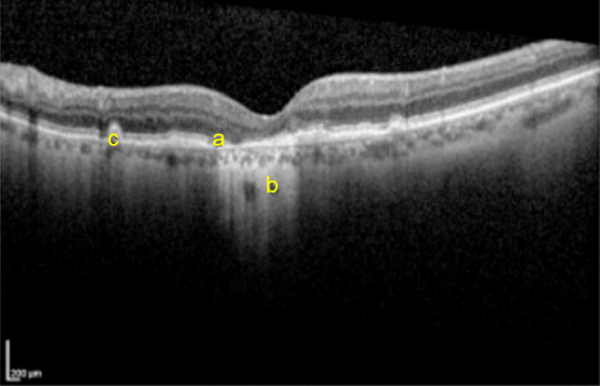

Ocular coherence tomography (OCT)

- High-resolution imaging of the retina that can be used to assess the thickness of the retinal layers, and the presence of retinal fluid (Figure 7).

Fluorescein angiography

- Imperative when treatable choroidal neovascularisation is suspected.

- Definitive process for the detection of choroidal neovascularisation.

Indocyanine green (ICG) angiography

- Can be used for visualization of the deeper choroidal vessels in situations where the source of the leakage is obscured by a haemorrhage of the retina, and fluorescein may thus be ineffective.

Autofluorescent imaging

- Helps identify areas of geographic atrophy in late dry AMD

Management

There is no cure for AMD.1-3 Treatment is focused on maintaining functional sight for as long as possible and addressing quality of life issues as they arise. For the most part, management varies with the stage of the disease.

An Amsler grid should also be provided to patients so that they can regularly assess their vision at home.2 All providers should discuss any treatable risk factors with patients, including smoking, ocular sun exposure, cardiovascular health and diet.

Referral to ophthalmology is recommended at any point in the disease process, even if visual acuity is normal. Urgent referral within 2 weeks is warranted if wet AMD is suspected, as treatment should be started promptly to preserve sight (discussed below). Urgent referral is particularly important in patients presenting with visual distortion or rapid onset visual loss. 8

Dry AMD

Low vision refractory aids may be helpful early on.

In early, Dry AMD there is some proven benefit to providing patients with vitamin supplements, known as the AREDS2 formula.5*

- Exogenous antioxidants

- Vitamins C and E

- Beta-carotene

- Zinc

- Macular pigments

- Lutein

- Zeaxanthin

*It is important to note that vitamin supplements have no proven benefit in those with signs of late dry AMD/neovascular disease (in case patients ask you).5

Wet AMD

Wet AMD represents significant and rapidly progressive disease, therefore management must be more aggressive. Intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy has revolutionised the management of sight-threatening AMD.

Intravitreal anti-VEGF medications include:

- Aflibercept

- Ranibizumab

- Bevacizumab

- Pegaptanib

These are usually given monthly for three months, with the response to treatment dictating how often further doses are given. After anti-VEGF therapy, rates of visual loss stabilise in two-thirds of patients, while the other third of patients improve.1,2

Other management strategies

- Registration with the national centre for the blind

- Regular eyesight testing and notification to the road safety authority*

- Social work involvement

- Occupational therapy

- Psychology involvement in cases of adjustment/mood disorder.

*Most people with AMD are still able to drive if their visual acuity with both eyes open is 6/12 or better (the Snellen chart equivalent of reading a car number plate at 20 meters). Failure to meet this standard requires the patient to inform the DVLA and stop driving.

Complications and prognosis

Complications of intravitreal injections are most often benign and transient. They include:

- Chemosis (oedema of the conjunctiva)

- Scleral injection (swelling of conjunctival vessels and reddening the eye, i.e. bloodshot)

- A sensation of grittiness/itchiness localising to the injection site9

- Infection, including endophthalmitis (<1%) 9

- Retinal detachment (<1%)9

- Cataract formation (<1%)9

AMD is progressive, and patients with early or intermediate stage disease have a 1.3% and 18% risk of developing advanced AMD in the next 5 years, respectively.3 Moreover, patients with advanced AMD in one eye have a 43% chance of developing advanced disease in the other eye over 5 years too.3 As sight deteriorates, patients are also at greater risk of falls and fractures. The early recognition and management of AMD is key to staving off the progression to significantly sight-limiting disease.

Key points

- AMD is the most common cause of blindness in those over the age of 60 in Ireland and the UK.

- Increasing age is the primary risk factor. Other major risk factors include family history, smoking and UV exposure.

- AMD presents with progressive loss of central vision.

- Imaging is the mainstay of investigation, of which OCT is the most useful.

- There is no curative therapy to date:

- Treat AMD with low-vision aids and vitamins in the early stages.

- Treat neovascular AMD with intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.

References

- Bowling B. Kanski’s clinical ophthalmology, international edition (8th ed). Published in 2015.

- Batterbury M, Murphy, C.Ophthalmology 4th ed. Published in 2018.

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS). Published in 1999. [LINK]

- Haugsdal J, Sohn E. Age-Related Macular Degeneration: From One Medical Student to Another [online]. Published in 2018. [LINK].

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Published in 2001. [LINK]

- Voegtli R. The Amsler Grid. [CC BY-SA]. [LINK]

- National Eye Institute NI of H. Distorted Amsler Grid. [CC BY-SA]. [LINK]

- National Institute For Health And Care Excellence. Macular degeneration – age-related (Summary) – NICE CKS [Internet]. Published in 2016. [LINK]

- Ghasemi Falavarjani K, Nguyen Q. Adverse events and complications associated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: a review of literature. Published in 2013. [LINK]

Reviewer

Hadi Ziaei

Ophthalmology Registrar

Editor

Hannah Thomas