- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Anxiety can be defined as a constellation of psychological and physiological responses to a potential/uncertain threat and is an essential function of the central nervous system (CNS).

It is analogous to pain in that it is an unpleasant experience which exists to automatically motivate us to avoid harm.

This concept is important when understanding the aetiology of anxiety disorders: the thoughts and behavioural symptoms which characterise it (while disabling) derive from fundamental drives for self-preservation and are therefore difficult to resist.

Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health conditions globally, with lifetime prevalence estimates varying from 5% to 29%.1,2

They can also be highly debilitating. The YLD (years lived with disability) burden of anxiety disorders in the UK is equivalent to that of ischaemic heart disease and asthma combined.3

However, there remains a stigma attached to them, with assumptions that anxiety disorders indicate weakness or failure to cope with ordinary stress. This article will begin by exploring their aetiology and challenging these assumptions.

Aetiology

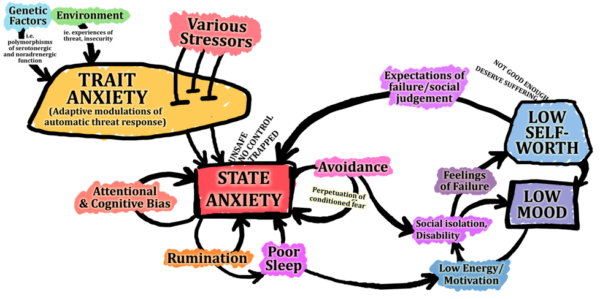

One straightforward way to understand the aetiology of anxiety disorders is as a collection of positive feedback loops (Figure 1).

Crudely speaking, there are several ways the brain can process anxiety, but under the wrong conditions (and/or given sufficiently prolonged and intense stressors) some of these automatic patterns of thought and behaviour can, themselves, perpetuate and worsen the anxiety.

This drives increasingly maladaptive coping strategies and these ongoing patterns gradually spiral into an illness.

The extent and nature of this spiral depend on a combination of the ways the brain tends to process anxiety to begin with (traits) and the severity of the stressors which have precipitated the disorder.

Trait anxiety

“Trait anxiety” is your propensity to experience the anxiety response (“state anxiety”, below) when exposed to a stressor.

It is a stable characteristic arising from a multitude of genetic and environmental factors, particularly adaptive responses to experiences of potential threat during development (for instance bullying, trauma, neglect or parental loss), as well as the nature of early attachment relationships*.

These experiences ‘calibrate’ the CNS response to a threat in adulthood. As you would expect, high trait anxiety confers a greater survival advantage – if an organism tends to avoid harm in dangerous situations, it is more likely to survive and reproduce (and this advantage mostly offsets the concomitant disadvantages of high trait anxiety). This is not only true in evolutionary history as high trait anxiety has been shown to improve survival even in modern western society.5

*Attachments in early life have profound and far-reaching ramifications for many areas of mental function (and dysfunction). In brief, the close and reciprocal relationship between an infant/child and its parent(s) is the crucible within which the developing brain learns how to think and feel. Through countless repeated daily experiences of being cared for, comforted when in pain, reassured when anxious – essentially, loved – a child gradually internalises and develops the ability to think, regulate emotion and cope with anxiety independently. For this development to take place, parental care simply needs to be “good enough” (the technical term in attachment psychology), but if this care is inconsistent, dismissive or perhaps even frightening, various problems can emerge, including high trait anxiety.4

State anxiety

“State anxiety” is simply the state of feeling anxious. This is not rocket science (we’re all familiar with the experience of anxiety), but like any illness, the disorder is identified when these symptoms become severe and persistent enough to cause significant distress and functional impairment.

Clinical features of state anxiety

Psychological symptoms: an unpleasant feeling of suspense, recurrent automatic thoughts about negative outcomes (rumination or “worrying”), reduced concentration, hypervigilance

Behavioural symptoms: avoidance of anxiogenic stimuli, restlessness/agitation

Physiological symptoms: palpitations, dyspnoea, muscle tension, disturbed sleep, fatigue, nausea

Signs: tachycardia, tachypnoea, tremor, sweating, pallor, pupil dilation (i.e. sympathetic nervous system arousal); also anxiety experienced by the observer (this is a feature of something called “countertransference” and is part of the normal unconscious communication of affective states from one person to another; it may complicate clinical encounters, but can also be a useful tool to gain insight into the patient’s state of mind).

Anxiety disorder

A combination of high trait anxiety and a critical mass of psychosocial stressors can overwhelm the normal homeostasis of anxiety and start to tip someone into a state of excessive and persistent anxiety in which normally harmless situations seem threatening.

Several processes are thought to drive this spiral and these are discussed below and summarised in Figure 1.

Avoidance

To motivate avoidance is largely the reason anxiety exists in the first place, but unfortunately, it minimises opportunities to unlearn your fear of a given stimulus.

This is a good thing in evolutionary terms*, but in this context, it can perpetuate existing anxiety associated with specific situations or stimuli (such as social interaction or crowded places).

*For instance, it’s not advantageous to easily unlearn fear of a particularly dangerous creature, because the next time you fail to avoid it, it might kill you. Therefore, it will take repeated exposures to uncouple anxiety from the stimulus.

Attentional and cognitive bias

State anxiety primes us to automatically pay attention to threats and to interpret ambiguous information as threatening.

This is useful to anticipate danger in a fight-or-flight situation, but in everyday circumstances (where the stressors driving state anxiety are often ubiquitous and cannot be easily escaped, i.e. pressure at school), this tendency to perceive threats in various situations is likely to heighten anxiety and increase the range of things you feel anxious about.

Anxious rumination

Rumination (continuously thinking about the same thing) occurs in various psychiatric disorders, and the process of recurrently thinking through possible catastrophic outcomes of one’s situation (also known as worrying) is another function of state anxiety which we can assume was useful in evolutionary terms; it is thought to represent an automatic attempt at problem-solving, which serves to maintain a state of vigilance for potential danger.6 However, again in this context, it may further increase state anxiety.

Low self-worth

Anxiety and depression are very frequently comorbid, and in many cases, it is almost meaningless to separate the two: they can often be thought of as one extensive network of feedback loops which generate both anxiety and depressive symptoms.7

Negative beliefs about yourself and associated low mood are components of depression which can be seen to both exacerbate anxiety (for instance if you feel you are incompetent, you will experience more anxiety about tasks you have to complete) and be exacerbated by anxiety (for example, feelings of failure associated with recurrently avoiding situations due to anxiety).

Poor sleep

Sleep serves countless essential functions related to cognition, emotional processing and memory (among many other things).

Therefore, it is no surprise that poor sleep appears to contribute to a host of problems including anxiety disorders, and as we know, state anxiety, in turn, results in poorer sleep.8

Figure 1 summarises some important basic principles, but it is not a comprehensive account of the aetiology of anxiety disorders.

The processes involved are extraordinarily complex, much is still to be discovered, and there are various alternative approaches to understanding it. This is a broadly cognitive-behavioural model, but it can also be understood in terms of psychodynamics, neuroinflammation, family systems, neuronal circuits. For those interested, here is a link to a more detailed, in-depth description.9

Neurobiology

Some of the key neurophysiological changes which underpin anxiety include:

- Reduced functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system (especially the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex): these connections are thought to subserve conscious control/awareness of emotional states.10

- Single nucleotide polymorphism variations in 5-HT (serotonin) transporter, resulting in diminished 5-HT signalling: this is the basis of the “Monoamine Hypothesis” of anxiety and depression11 and is the target of the most widely used antidepressants, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.12

- Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis: this is the term used to describe the self-regulating neuronal and hormonal interaction between the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland and the adrenal glands, which is a central component of the physiological response to stress (see here for more information).13

The question of whether these changes are a cause of the psychological processes described above, or a result of them, is a matter of debate.

They are simultaneously both and are best thought of as two sides of the same coin (or like the magnetic and electric fields of an electromagnetic wave, simultaneously generating and being generated by one another, inextricable facets of a single process).

Interestingly, changes on fMRI in the brains of patients with anxiety or depression have been demonstrated following pharmacological or psychological treatment.14

Types of anxiety disorder

The distinctions between different anxiety disorders (below) help to describe and group symptoms, but at a basic level, they are broadly similar in terms of psychopathology and symptoms often overlap.

The diagnostic criteria listed below are taken from ICD-10 with some additions from ICD-11.

To meet the diagnostic criteria for any of them (including “related disorders” below), symptoms must:

- Persist for several months, on more days than not

- Result in significant impairment (in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning)

- Not be a manifestation of another health condition or the effects of a substance/medication

Generalised anxiety disorder

Persistent “free-floating” anxiety (not restricted to/predominant in any specific circumstances), or excessive worry focused on multiple everyday events.

Common features of generalised anxiety disorder include:

- Subjective experience of nervousness

- Difficulty maintaining concentration

- Muscular tension or motor restlessness

- Sympathetic autonomic over-activity

- Irritability

- Sleep disturbance.

Lifetime prevalence of 5-12%15 ♀>♂

Phobic anxiety disorders

Abnormal state anxiety evoked only/predominantly by a specific external situation/object which is not currently dangerous. The key feature is the avoidance of that situation.

Types of phobic anxiety disorders include:

- Agoraphobia (crowds, public places, leaving home ♀>♂)

- Social phobia (associated with low self-esteem and fear of criticism. ♂=♀)

- Specific phobias (e.g. claustrophobia, animal phobias, etc.)

Characteristic features include:

- Anticipatory anxiety (about exposure to precipitant, and about anxiety itself)

- Somatic symptoms (e.g. palpitations, sweating, trembling, dyspnoea, chest pain, dizziness, chills, hot flushes)

Lifetime prevalence is up to 12% (estimates vary).16

Panic disorder

Recurrent unpredictable episodes of severe acute anxiety, which are not restricted to particular stimuli or situations.

Characteristic features include:

- A crescendo of anxiety, usually resulting in exit from the situation

- Somatic symptoms (e.g. palpitations, sweating, trembling, dyspnoea, chest pain, dizziness, chills, hot flushes)

- Secondary fear of dying/losing control (often related to the somatic symptoms)

Lifetime prevalence of 4.7%17 ♀>♂

Management

In the treatment of anxiety disorders, psychological therapies address the problem (for instance by helping the patient to break some of the positive feedback loops described above), and medications reduce the intensity of state anxiety to better enable the person to engage with psychology.

Often both approaches are essential. Treatment is effective but takes time and significant effort because the patient is required to go against their innate self-protective impulses (such as avoidance).

The stepwise treatment algorithm, depending on severity, is as follows:18

- Psychoeducation, sleep hygiene, and self-guided cognitive-based therapy (CBT)/ relaxation techniques: it may be helpful to acknowledge that these can appear basic/low intensity, but emphasise their evidenced effectiveness for mild/moderate anxiety if done regularly.

- CBT: identifying then gradually unlearning the maladaptive patterns of thought/behaviour which are perpetuating symptoms. A CBT practitioner may employ techniques such as exposure therapy (allows extinction of erroneously learned fears) and applied relaxation.

- Pharmacological (equal 1st line with CBT). SSRI (e.g. escitalopram or sertraline), SNRI (e.g. duloxetine or venlafaxine) or atypical antidepressant (e.g. Mirtazapine) with the choice depending on side-effect profile.

Benzodiazepines

Avoid benzodiazepines (e.g. diazepam) for chronic anxiety.

Due to their immediate effects (resulting in powerful negative reinforcement), this group of drugs is highly addictive. Tolerance develops rapidly, so after a month or two of benzodiazepines, your patient will be back to the same level of anxiety but also addicted to benzodiazepines.

They can be used for transient causes of anxiety (ie. fear of flying) or in crisis only, maximum of 2 weeks prescription advised.

Other related disorders

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

PTSD may develop following exposure to an extremely threatening/horrific event or series of events. It is thought to result from impaired memory consolidation of experiences too traumatic to be processed normally, which leads to a chronic hyperarousal of fear circuits.

Characteristic features of PTSD include (remember using the mnemonic HARD):

- Hyperarousal: persistently heightened perception of current threat (may include enhanced startle reaction)

- Avoidance of situations/activities reminiscent of the events, or of thoughts/memories of the events

- Re-experiencing the traumatic events (vivid intrusive memories, flashbacks, or nightmares).

- Distress: strong/overwhelming fear and physical sensations when re-experiencing

Management of PTSD includes:

- Trauma-focused CBT

- Eye-Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy

- Pharmacological: SSRI or venlafaxine (possible adjunctive antipsychotic)

- Plus psychoeducation/sleep hygiene/ relaxation etc. as above.

Lifetime prevalence of 2-6%19 ♀>♂

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD)

C-PTSD is a disorder that may develop following exposure to series of extremely threatening/horrific events, commonly prolonged or repetitive situations from which escape is difficult (e.g. torture, slavery, genocide campaigns, prolonged domestic violence, repeated childhood sexual or physical abuse).

C-PTSD can be thought of as a constellation of significant modifications to a person’s automatic threat response, occurring because of having to adapt to prolonged/repetitive trauma.

This tends to leave the brain especially vulnerable to subsequent traumatic experiences later in life. C-PTSD has many similarities to emotionally unstable personality disorder (EUPD) and indeed is considered by many to be a more helpful/less stigmatising way to describe some cases of EUPD.

Characteristic features of C-PTSD include all diagnostic requirements for PTSD (above), plus:

- Severe and persistent problems in affect regulation

- Severe and persistent low self-worth, accompanied by feelings of shame/guilt/failure related to the traumatic events

- Severe and persistent difficulties in sustaining relationships and in feeling close to others.

Treatment of C-PTSD is similar to PTSD. It may require more long-term psychological therapy.

Obsessive-compulsive or related disorders

A group of disorders characterised by repetitive thoughts and behaviours, including:

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD)

- Body-focused repetitive behaviour disorders (ie. trichotillomania, dermatillomania)

- Hypochondriasis (health anxiety disorder)

- Hoarding disorder

Typically, the repetitive thoughts are intrusive and distressing (in the case of OCD, BDD and Hypochondriasis), and the repetitive behaviours are compulsive/ habitual means of reducing distress which becomes difficult for the person to control (in the case of OCD, trichotillomania/ dermatillomania, and also hoarding disorder which is characterised by distress associated with discarding possessions).

Anxiety is a prominent feature of these disorders. The repetitive thoughts drive and are driven by it, and the compulsive behaviour’s function to reduce it. Furthermore, many of the anxiety disorders described above can also feature repetitive intrusive thoughts (ie. related to rumination).

Treatment of these disorders is similar to other anxiety disorders, usually a combination of SSRI and psychological therapy.

Specific types of CBT may be used, for instance, exposure and response prevention therapy for OCD.

Other types of medication may be indicated if not responding to SSRI, for instance, clomipramine (a tricyclic antidepressant) or adjunctive antipsychotics.

Anxiety and medical students

Anxiety disorders are common and can affect anyone. However, these disorders are known to be especially common among medical students, with around one in three medical students affected globally.20

Of course, a degree of anxiety is appropriate and adaptive for doctors, helping to maintain vigilance and motivation to deliver safe care. But as we have seen, if anxiety is intense and persistent to the point of overwhelming the normal homeostasis, it can develop into a disorder.

It is important to remember that there is a gradual continuum between everyday stress and severe anxiety disorder, and wherever you may find yourself on that spectrum there are interventions that can prevent anxiety from advancing.

Good sleep hygiene and self-guided anxiety management strategies are highly effective at any stage if performed regularly, but it is also important to speak to your GP or someone in a position of pastoral responsibility if anxiety disorder seems to be developing.

There is a difficult balance to be struck here, between two different narratives that apply to varying degrees at either end of the spectrum of anxiety: that anxiety is something that you can cope with yourself, or that anxiety is an illness that requires input from health professionals.

We are bombarded by these opposite messages in various forms, and it is all too easy for them to fuel the illness further; we may either start to believe that we are to blame for an established anxiety disorder because we were not “resilient enough” and did not cope with it effectively ourselves (reinforcing low self-worth), or that we have an illness and are therefore unable to manage anxiety independently (undermining the various self-help strategies available to us). A capacity to reflect insightfully and honestly on this is a valuable skill, both for ourselves and our patients.

Further resources can be found here:

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. Anxiety, panic and phobias.

- Mind. Anxiety and panic attacks.

- The Mix

Reviewer

Dr Johan Redelinghuys

Consultant Child & Adolescent Psychiatrist

Editor

Hannah Thomas

References

- Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser. Mental Health-Our World. Published in 2018. [LINK]

- NICE CG113. Anxiety: management of generalised anxiety disorder in adults in primary, secondary and community care (update). Published in 2019. [LINK]

- Global Health Data Exchange. [LINK]

- Duncan Mascarenhas, Nickolas Smith. Developing the Performance Brain: Decision Making under Pressure- Trait Anxiety. Published in 2011. [LINK]

- Lee WE, Wadsworth MEJ, Hotopf M. The protective role of trait anxiety: a longitudinal cohort study. Published in 2006. [LINK]

- Grierson AB, Hickie IB, Naismith SL, Scott J. The role of rumination in illness trajectories in youth: linking trans-diagnostic processes with clinical staging models. Published in 2016. [LINK].

- Courtney Beard et al. Network Analysis of Depression and Anxiety Symptom Relations in a Psychiatric Sample. Published in 2017. [LINK]

- Pasquale K. Alvaro, Rachel M. Roberts, Jodie K. Harris. A Systematic Review Assessing Birectionality between Sleep Disturbances, Anxiety and Depression. Published in 2013. [LINK]

- Thibaut F. Anxiety disorders: a review of current literature. Published in 2017. [LINK]

- Tovote P, Fadok JP, Lüthi A. Neuronal circuits for fear and anxiety. Published in 2015. [LINK]

- OpenLearn. Understanding depression and anxiety. Published in 2019. [LINK]

- NHS. Overview of SSRIs. Published in 2018. [LINK]

- Faravelli C, et al. The role of life events and HPA axis in anxiety disorders: a review. Published in 2012. [LINK].

- Fournier JC, Price RB.Psychotherapy and Neuroimaging. Published in 2014. [LINK].

- David Baldwin. Generalized anxiety disorder in adults: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. Published in 2018. [LINK]

- NICE CG159. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Published in 2013. [LINK]

- Peter P Roy-Byrne. Panic disorder in adults: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, course, assessment and diagnosis. Published in 2019. [LINK]

- NICE QS53. Anxiety Disorders Quality Standard. Published in 2014. [LINK]

- Jitender Sareen. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. Published in 2020. [LINK]

- Quek TT, Tam WW, Tran BX, et al. The Global Prevalence of Anxiety Among Medical Students: A Meta-Analysis. Published in 2019. [LINK].