- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Epistaxis, or nosebleed, is a common presenting complaint that occurs in up to 60% of the adult population. It has a bimodal age distribution, occurring commonly before age 10 or between the ages of 45 and 65.1,2

Epistaxis may be categorised as anterior or posterior depending on the origin of bleeding within the nasal cavity. Identifying the site of the bleed is crucial for management, and this skill depends on an understanding of the vascular supply of the nose.

Additionally, nosebleeds may be divided into primary bleeds which arise spontaneously and secondary bleeds which occur due to another cause.

This article will cover the assessment and management of epistaxis in general.

Aetiology

The secondary causes of epistaxis can be broken down into six categories:

- Trauma

- Intranasal drugs (e.g. decongestants, steroids or illicit drugs)

- Weather

- Anatomical variants (e.g. deviated septum)

- Systemic causes

- Tumours

Clinical anatomy

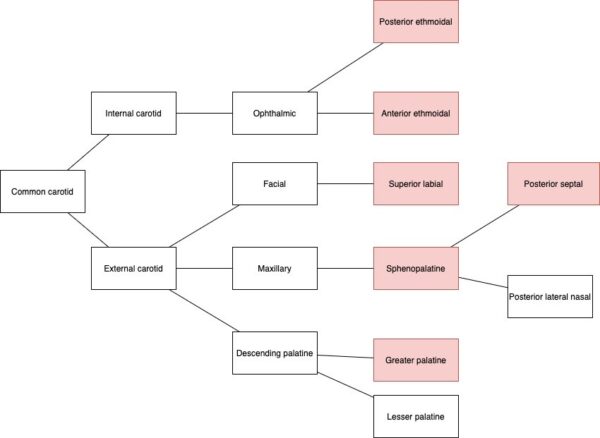

The most clinically relevant anatomy to epistaxis is the nasal vascular supply. For conciseness, only the vascular anatomy is discussed in this article.

There are two main principles to understand regarding the nasal cavity:

- The first is that there is dual arterial supply from both the internal and external carotid arteries.

- The second principle is that most bleeds originate anteriorly in the nasal cavity in Little’s area within Kiesselbach’s plexus. This area is particularly vulnerable to dryness and trauma.

With these principles in mind, the anatomy of the nasal cavity can be examined in greater detail.

Anterior septum

The major vascular structure of the anterior nasal cavity is Kiesselbach’s plexus. This is an anastomotic network formed from multiple arteries, although there is variation in the literature regarding which vessels should be considered part of the plexus.

The following arteries are generally accepted as contributing to Kiesselbach’s plexus:3-5

- The sphenopalatine artery (external carotid origin)

- The ascending branch of the greater palatine artery (external carotid origin)

- The septal branch of the superior labial artery (external carotid origin)

- The anterior ethmoid artery (internal carotid origin)

Some authors suggest that while the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries supply the superior region of the nasal septum, they do not form part of Kiesselbach’s plexus per se.

Woodruff’s plexus

Woodruff’s plexus is a series of veins on the inferolateral aspect of the nasal cavity. It was historically thought to be a confluence of arteries as well as the most common site of posterior nasal bleeds. However, recent research to characterise the area suggests that it is a venous plexus, and its association with posterior epistaxis may be overstated.6

Lateral wall

The lateral aspect of the nasal cavity receives much of its arterial blood supply from the posterior lateral nasal (PLN) branch of the sphenopalatine artery. The upper portion of the lateral wall is also supplied partially by the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries.

Venous drainage

Veins accompany the various arteries, coursing towards the facial vein, pterygoid plexus and ophthalmic veins.

The finer points of the vascular anatomy of the nasal cavity are still a point of investigation and are beyond the scope of this article.7-9

Risk factors

There are several risk factors for the development of epistaxis:10-14

- Age below 10 or above 65:

- Young children frequently experience epistaxis, due in part to high rates of digital trauma and recent viral upper respiratory tract infections.

- The increased risk in elderly patients may be due to a higher prevalence of vascular comorbidities such as atherosclerosis and hypertension.

- Rhinitis, both allergic and non-allergic

- Viral or bacterial sinusitis

- High ambient temperature

- Septal deviation

- Bleeding disorders

- Decompensated heart failure

- Cocaine use

- Trauma with facial injury

- Hepatic or renal impairment

- Anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs

- Frequent use of intranasal steroids and decongestants

Hypertension

There is a correlation between uncontrolled hypertension and recurrent epistaxis, although a causative relationship has not been established.15-18

Some research suggests chronic hypertension is associated with an increased risk of recurrent epistaxis.11,19

Hypertension may prolong the bleeding during an episode of epistaxis. However, studies have not been able to confirm this association.20,21

Clinical features

History

It is important to obtain a detailed description of the epistaxis, including:

- Which side the bleed originated from, and whether it began anteriorly or posteriorly: Asking whether the patient has noticed the sensation of blood dripping down their throat may help to distinguish between anterior and posterior bleeds.

- The duration of the bleed

- Whether the bleed is unilateral or bilateral

- Treatment already performed to stop the bleeding

- Whether this has occurred before and if so, is it similar to those episodes?

- What the patient was doing just before the epistaxis started

- How much blood was lost

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Medical history (e.g. profuse post-operative bleeding, easy bruising, multiple blood transfusions)

- Medication history (e.g. anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs, intranasal sprays)

- Family history (e.g. first or second-degree relative with bleeding diathesis)

- Alcohol and illicit drug use

Clinical examination

In the context of an episode of epistaxis, examination of the nasal cavity is required. See the Geeky Medics guide here for further information on performing a nasal examination.

Features to look for during the examination include:

- An actively bleeding vessel

- Septal deviation or perforation

- Polyps or other masses

- Foreign body

- Mucosal discolouration

- Hyperaemia

- Enlarged turbinates

Differential diagnoses

Although many presentations with epistaxis are primary, it is important to have a systematic approach when considering an underlying cause to avoid missing serious pathologies.

Secondary causes of epistaxis can be divided into local and systemic. The patient’s age can then be used to narrow down the likely list of differentials further.

Table 1. The secondary causes of epistaxis

| Local | Systemic | |

| Adults |

Trauma Individual anatomical differences (e.g. septal deviation) Neoplasm (most commonly squamous cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, melanoma and inverted papilloma) Bacterial sinusitis Topical or illicit medications |

Anticoagulant medications Alcohol Von Willebrand disease Granulomatosis with polyangiitis Chemotherapeutic drugs |

| Children or adolescents |

Trauma (often from nose picking) Inflammatory conditions (see above) Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma |

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) Von Willebrand disease |

Alternatively, a surgical sieve such as VINDICATE may be used to generate a broad list of differentials for epistaxis.

Tabe 2. The secondary causes of epistaxis using a surgical sieve

| Category | Pathology |

| Vascular | Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma |

| Infective/inflammatory |

Sarcoidosis Tuberculosis Acute sinusitis |

| Neoplastic |

Juvenile angiofibroma Squamous cell carcinoma Adenoid cystic carcinoma Inverted papilloma |

| Degenerative | – |

| Iatrogenic/intoxication |

Topical antihistamines/decongestants/steroids Alcohol consumption Snorting cocaine Nasogastric tube Endotracheal intubation |

| Congenital |

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) Von Willebrand disease Haemophilia |

| Autoimmune |

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis Sarcoidosis |

| Trauma |

Facial fracture Nose picking Foreign body |

| Endocrine | – |

Don’t miss diagnoses

The following clinical features may suggest a more serious underlying diagnosis.

- Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: unilateral bleeding, progressive hoarseness, dysphagia, hearing loss, significant smoking history, Southeast Asian descent.

- Juvenile nasal angiofibroma: younger patients with unilateral epistaxis.

- Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT): young age, family history of HHT, partially blanching cutaneous lesions.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations

- Baseline blood tests (FBC): patients with profuse bleeding should have two wide-bore cannulae inserted with blood taken for a full blood count.

- Group and save: important to perform as the patient may require a blood transfusion.

- Coagulation studies: should be performed if there is clinical evidence of coagulopathy, or the patient is taking an anticoagulant.22, 23

Imaging

Radiographic or nuclear imaging is not routinely recommended for patients with epistaxis, although this depends on the context of the presentation. Imaging is performed if a complete examination of the sinonasal cavity is not possible due to the patient’s anatomy.

A patient with epistaxis due to a facial fracture will require imaging of the facial bones. In addition, a rigid or flexible nasal endoscopy may be needed to visualise the source of bleeding if anterior rhinoscopy is insufficient.

Management

The management of epistaxis should always take into consideration how acutely unwell the patient is, the risk of airway compromise and the likelihood of the bleed resolving with simple interventions.24

Emergency management

Although most episodes of epistaxis resolve spontaneously, massive haemorrhage and airway compromise can occur. This usually occurs in the setting of underlying pathology, for example, hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

It is important to take an ABCDE approach when managing patients with profuse bleeding.

Emergency management should include:

- A rapid ABCDE assessment: including the insertion of two wide-bore cannula and fluid resuscitation as required to achieve haemodynamic stability.

- Basic first aid measures: pinch the soft, lower cartilaginous portion of the nose and hold this for at least ten minutes and apply an ice pack to the bridge of the nose to support vasoconstriction.

Management of anterior epistaxis

First-line treatment of an anterior bleed is chemical or electrical cautery which can be combined with local anaesthetic and topic vasoconstrictors. Always follow local guidelines for the management of epistaxis.

Performing chemical cautery

One method for performing chemical cautery is the bait-and-switch approach.7

The principle is to alternate between using cotton balls soaked with local anaesthetic and short bouts of chemical cautery with silver nitrate sticks.

- After using anterior rhinoscopy or endoscopy to visualise the bleeding, use Tilley nasal forceps to apply the anaesthetic-soaked cotton ball to the bleeding vessel. Chemical cautery requires a dry environment.

- Press the head of the cautery stick against the affected area with just enough pressure to compress the underlying vessel.

- Use a rolling motion to continue the application to the adjacent areas.

- Cauterise only the appropriate areas, not the entire nasal septum or wide swathes of the nasal cavity.

- Limit the contact time between the cautery stick and the nasal mucosa. Usually, five to ten seconds is sufficient.

- Do not cauterise the same area repeatedly, or the same area on both sides of the nasal septum as this can result in a septal perforation.

- Explain proper after-care to the cauterised patient, emphasising saline nasal irrigation from the day after the encounter.

In the case of a bleed that does not resolve with cautery, anterior nasal packing is the second-line treatment.

- Packing products include nasal tampons, ribbon gauze, balloon catheters and gel or foam thrombogenic agents.

- The Rapid Rhino™ balloon catheter is a commonly used device for anterior nasal packing.

- Inserting or inflating a pack can be quite painful. Prescribe appropriate analgesia depending on the situation.

- Some guidelines may recommend prophylactic antibiotics with anti-staphylococcal activity to prevent toxic shock syndrome.

- Packed patients should be reviewed 24-48 hours after the pack is inserted.

Posterior bleeds

The first-line treatment for posterior bleeds is packing. Posterior bleeds can be difficult to detect but should be suspected in patients with persistent bleeding despite bilateral anterior packing.

Materials for posterior packing include a Foley catheter, ribbon gauze lubricated with vaseline or bismuth iodoform paraffin paste (BIPP), Tilley forceps, tongue depressors and an umbilical clamp.

The principle of posterior packing with a balloon catheter is to thread the catheter through the nasal cavity and inflate the balloon when situated appropriately.

Patients with posterior packs are usually admitted to hospital while the packing is in situ, due to the increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, hypoxic episodes and death.

Surgical management

Surgical management involves ligation of the sphenopalatine, internal maxillary or anterior ethmoid arteries.

Surgery is indicated in the following situations:

- Life-threatening bleeding (emergency surgery)

- Patient’s bleeding has resolved but is at a high risk of re-bleeding

- Follow-up surgery for a patient who is suspected to have a malignancy which could not be visualised in the first operation.

Angiographic embolisation of the sphenopalatine artery may also be performed, although this carries the risk of vascular complications including ischaemic stroke and blindness.25, 26

Complications

Although the majority of bleeds resolve spontaneously, complications may include:27

- Hypovolaemic shock

- Aspiration

- Intranasal adhesions

- Mucosal damage from excessive cautery

- Infected nasal packing

Key points

- The majority of nosebleeds originate anteriorly in the nasal cavity from Kiesselbach’s plexus.

- Most nosebleeds arise idiopathically, but local and systemic aetiologies can contribute.

- Patients with epistaxis must be clinically stabilised according to the ABCDE principles before further management.

- Patients should be instructed to lean forward and pinch the nasal ala together for at least 10 minutes.

- Anterior rhinoscopy or rigid endoscopy should be used to localise the source of the bleed.

- First-line treatment of an anterior bleed is chemical or electrical cautery.

- Patients whose bleeding does not resolve with cautery should receive anterior packing.

- Posterior bleeds should receive packing and be hospitalised with cardiac monitoring until follow-up with a specialist.

- Surgical management of epistaxis may include sphenopalatine artery ligation or angiographic embolisation of the sphenopalatine artery.

Reviewers

Professor Peter-John Wormald

Chairman Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery

Professor of Skull Base Surgery

University of Adelaide, South Australia

Associate Professor Alkis J. Psaltis

Head of Department

Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery

The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Adelaide, South Australia

Associate Professor

Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery

University of Adelaide, South Australia

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Kucik CJ & Clenney T. Management of epistaxis. 2005.

- Pallin DJ, Chng YM, McKay MP, Emond JA, Pelletier AJ & Camargo CA, Jr. Epidemiology of epistaxis in US emergency departments, 1992 to 2001. 2005.

- Sinnatamby CSF (2011). Head and neck and spine. In Last’s Anatomy edn, ed. Sinnatamby CSF, 329-454.

- Middleton PM. Epistaxis. 2004.

- MacArthur FJD & McGarry GW. The arterial supply of the nasal cavity. 2017.

- Chiu TW, Shaw-Dunn J & McGarry GW. Woodruff’s plexus. 2008.

- Scott JR, Psaltis AJ & Wormald P-J. Vascular Anatomy of the Inferior Turbinate and Its Clinical Implications. 2020.

- Shams PN, Wormald PJ & Selva D. Anatomical landmarks of the lateral nasal wall: implications for endonasal lacrimal surgery. 2015.

- Touzet-Roumazeille S, Nicol P, Fontaine C & Vacher C. Anatomic study of the arterial territories of the face depending on the external carotid artery branches. 2020.

- Nunez DA, McClymont LG & Evans RA. Epistaxis: a study of the relationship with weather. 1990.

- Okafor BC. Epistaxis: a clinical study of 540 cases. 1984.

- Juselius H. Epistaxis. A clinical study of 1,724 patients. 1974.

- Lund VJ, Preziosi P, Hercberg S, Hamoir M, Dubreuil C, Pessey JJ, Stoll D, Zanaret M & Gehanno P. Yearly incidence of rhinitis, nasal bleeding, and other nasal symptoms in mature women. 2006.

- Manfredini R, Gallerani M & Portaluppi F. Seasonal variation in the occurrence of epistaxis. 2000.

- Kotecha B, Fowler S, Harkness P, Walmsley J, Brown P & Topham J. Management of epistaxis: a national survey. 1996.

- Schaitkin B, Strauss M & Houck JR. Epistaxis: medical versus surgical therapy: a comparison of efficacy, complications, and economic considerations. 1987.

- Pritikin JB, Caldarelli DD & Panje WR. Endoscopic ligation of the internal maxillary artery for treatment of intractable posterior epistaxis. 1998.

- Abrich V, Brozek A, Boyle TR, Chyou PH & Yale SH. Risk factors for recurrent spontaneous epistaxis. 2014.

- Min HJ, Kang H, Choi GJ & Kim KS. Association between Hypertension and Epistaxis: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. 2017.

- Petruson B, Rudin R & Svardsudd K. Is high blood pressure an aetiological factor in epistaxis?. 1977.

- Lubianca Neto JF, Fuchs FD, Facco SR, Gus M, Fasolo L. Mafessoni R & Gleissner AL. Is epistaxis evidence of end-organ damage in patients with hypertension? 1999.

- Thaha MA, Nilssen EL, Holland S, Love G & White PS. Routine coagulation screening in the management of emergency admission for epistaxis–is it necessary? 2000.

- Shakeel M, Trinidade A, Iddamalgoda T, Supriya M & Ah-See KW. Routine clotting screen has no role in the management of epistaxis: reiterating the point. 2010.

- Yau S. An update on epistaxis. 2015.

- White PS. Endoscopic ligation of the sphenopalatine artery (ELSA): a preliminary description. 1996.

- Wormald PJ, Wee DTH & van Hasselt CA. Endoscopic Ligation of the Sphenopalatine Artery for Refractory Posterior Epistaxis. 2000.

- Pollice PA & Yoder MG. Epistaxis: a retrospective review of hospitalized patients. 1997.