- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Being able to share information in a clear and concise way is an essential skill in all fields of medicine. This can range from simple explanations, such as why a blood test may be needed, to more complex situations, such as explaining a new diagnosis. Often, sharing information with a patient occurs naturally during a consultation. However, providing clinical information may also be the primary focus of an appointment, and in these situations, it is crucial to have a structured format to communicate effectively.

There are an estimated 4 million people living with diabetes in the UK, which represents 6% of the population. This means that understanding how to explain a diagnosis of diabetes is a key clinical skill. This guide is a step-by-step approach to explaining a diagnosis of diabetes and should be used in conjunction with our “Information giving – an overview” guide.

Structure

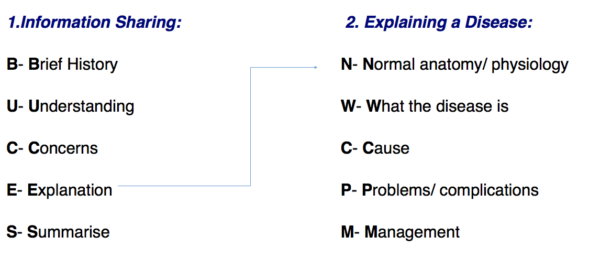

Explaining a diagnosis requires structure and adequate background knowledge of the disease. Whether the information being shared is about a procedure, a new drug or a disease, the BUCES structure (shown below) can be used.

Opening the consultation

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

BUCES can be used to remember how to structure a consultation in which providing information is the primary focus. Before explaining the various aspects of a disease, it is fundamental to have a common starting point with your patient. This helps to establish rapport and creates an open environment in which the patient can raise concerns, ask questions and gain a better understanding of their problem. After introducing yourself, it is important to take a brief history (this is the first part of the BUCES structure):

- What has brought the patient in to see you today?

- What are their symptoms?

- Are there any risk factors that can be identified? (e.g. lifestyle/family history)

For example, a diabetic patient may describe feeling very tired, urinating often and feeling very thirsty.

Tip: Practice taking concise histories to get the timing right. In OSCE stations, timing is crucial and you do not want to spend all your time taking a history when you are meant to be explaining a diagnosis! A rough guide would be to keep the introduction and brief history between 1-2 minutes maximum.

What does the patient understand?

Following a brief history, it is important to gauge the patient’s knowledge of their condition. Some patients may have a family member with diabetes and therefore have a fairly good understanding of what the condition entails (be careful to differentiate between insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent). Other patients may have heard of diabetes, but only have a vague understanding of the important details. The patient sitting before you may not even know at this point that they have diabetes – you may be the first person to inform them of the diagnosis.

Due to these reasons, it is important to start with open questioning. Good examples include:

- “What do you think is causing your symptoms?”

- “What do you know about diabetes?”

- “What has been explained to you about diabetes so far?”

Open questioning should help you to determine what the patient currently understands, allowing you to tailor your explanation at an appropriate level.

At this stage, primarily focus on listening to the patient. It may also be helpful to give positive feedback as the patient talks (i.e. should a patient demonstrate some understanding, reinforce this knowledge with encouraging words and non-verbal communication such as nodding).

Checking the patient’s understanding should not be solely confined to this point of the consultation but should be done throughout by repeatedly ‘chunking and checking’.

Tip: Try using phrases such as: “Just to check that I am explaining diabetes clearly, can you repeat back to me what you understand so far?”. This is far better than only saying “What do you understand so far?” as the onus is placed upon the quality of your explanation rather than there being an issue with the patient’s ability to understand.

At this point, it can also be helpful to determine whether the patient understands what management options are available and to ascertain what is most important to the patient.

What are the patient’s concerns?

The patient’s concerns should never be overlooked. A diagnosis of diabetes can be a significant life event and provoke a variety of worries. Asking the patient if they have any concerns before beginning your explanation allows you to specifically tailor what is most relevant to the patient, placing them at the centre of the explanation. The “ICE” (ideas, concerns and expectations) format, can provide a useful structure for exploring this area further.

ICE

Ideas:

- What does the patient think is causing their symptoms?

- What is their understanding of the diagnosis?

Concerns:

- What are the patient’s concerns regarding their symptoms and diagnosis?

Expectations:

- What is the patient hoping to get out of the consultation today?

Explanation

After determining the patient’s current level of understanding and concerns, you should be able to explain their condition clearly. Diabetes can be confusing to medical students and doctors, let alone patients. Avoid medical jargon so as not to confuse your patient.

You should begin by signposting what you are going to explain to give the patient an idea of what to expect.

Diabetes can be explained by using the metaphor of a car, a key and a garage.

Tip: Use the mnemonic “Normally We Can Probably Manage” to help you remember the structure of explaining a disease.

Normal anatomy/physiology

“After we eat a meal, the food is broken down into sugar, which is released into our blood. This sugar is the fuel for all the cells that make up our body, and needs to get from the blood into the cells for them to function properly.”

Explain to the patient that they should think of sugar like a car, insulin like a key and the cells in their body as a garage.

“When you drive home, you use your key, the garage opens and you can park your car. This is what normally happens in our body too. If we imagine sugar is the car, the cells are the garage, and a hormone called insulin is the key, sugar can only enter the cells when insulin is working properly.”

What the disease is

“In diabetes, the sugar cannot get into the cell as the insulin is not working properly. If we think of it in terms of a car not being able to get into the garage – this would cause congestion on the roads. This also happens with sugar – it cannot get into the cells and therefore builds up in the tubes of the body which supply the cell with blood. This build-up of sugar in the blood can cause damage to the cells if it remains too high for too long – whether that be the cells of the heart, eyes, liver, kidneys etc.”

Cause of the disease

There are two main causes of diabetes and both centre around problems with insulin.

Type 1 diabetes involves a combination of genetic and environmental factors (e.g. viral infections as an initial trigger for the disease) that ultimately results in the patient’s immune system destroying their insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. As a result, they are no longer able to produce insulin and are therefore reliant on insulin injections for the rest of their life.

Type 2 diabetes also involves a combination of genetic and environmental factors (e.g. diet, obesity and overall lifestyle). People with type 2 diabetes have a combination of inadequate insulin production and increased insulin resistance (the cells ignore the insulin and don’t allow the sugar in).

Problems/complications

Outlining potential complications of diabetes is necessary so that the patients can identify problems early and seek medical advice. Being aware of common problems will encourage patients to adhere to their treatment and remain vigilant.

It is important not to scare the patient, but to explain that you are outlining the potentials risks so that they are aware of them. When discussing potential complications explain that you and the patient will need to work together as a team to reduce the likelihood that they’ll occur.

Link the build-up of sugar in the blood back to the complications of diabetes. For example, high levels of sugar in the blood can damage the blood vessels of:

- the kidneys causing kidney failure

- the heart which can increase the risk of heart attacks

- the brain which can increase the risk of stroke

- the eyes causing loss of vision

- the nerves of the lower limbs causing peripheral neuropathy

Also, outline how diabetes can cause slow healing of wounds and explain the risk of diabetic ulcers (including what these look like).

Tip: Offer a leaflet about diabetes, including advice on foot care and tell the patient that they will be meeting other members of the team including a specialist nurse who will help to coordinate their care.

Management

Reinforce to the patient that they need to work with you as a team to achieve a good result.

Start by explaining what the patient can do to manage their condition. Including:

- Lifestyle change: healthy diet (avoiding foods high in sugar), losing weight, regular exercise

- Stop smoking (if relevant)

- Emphasise the importance of tight glycemic control

- Attending diabetic checks

- Encourage good foot care and regular podiatrist appointments

Then explain how you as the doctor will be managing their condition. Important points include:

- Regular check-ups to screen for diabetic complications

- Regular blood tests to check blood sugar levels

- Counselling on starting metformin (this helps the garage recognise the key i.e. increases insulin sensitivity) or other oral hypoglycaemics

- Managing any complications as they arise

Closing the consultation

Summarise the key points back to the patient.

Ask the patient if they have any questions or concerns that have not been addressed.

“Is there anything I have explained that you’d like me to go over again?”

“Do you have any other questions before we finish?”

Arrange appropriate follow-up to discuss their diabetes further. Acknowledge that you have discussed a large amount of information and it is unlikely that they will remember everything.

Offer the patient some leaflets on diabetes and its management, and direct them to some reliable websites which they can use to gather more information (examples include patient.info and NHS Choices).

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Editor

Andrew Gowland