- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Extradural haematoma (EDH) is defined as an acute haemorrhage between the dura mater and the inner surface of the skull.

An EDH can cause compression of local brain structures and a rise in intracranial pressure. If intracranial pressure continues to rise, cerebellar herniation may occur leading to brainstem death.

Patients most commonly affected by extradural haematomas (EDH) are adult males between the ages of 20 – 30.

Aetiology

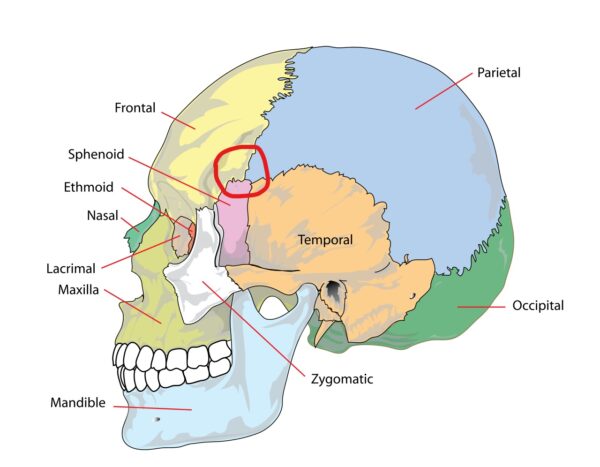

An extradural haematoma is commonly caused by skull trauma in the temporoparietal region, typically following a fall, assault or sporting injury. An EDH is associated with a skull fracture in 75% of cases.

The pterion is an anatomical landmark where the parietal, frontal, sphenoid and temporal bones fuse. The pterion is particularly vulnerable to fracture as the bone at this location is relatively thin.

The middle meningeal artery (MMA) also lies underneath the pterion and therefore fracture at this location can result in rupture of the MMA. As a result, the middle meningeal artery is involved in 75% of extradural haematomas.

EDH can also occur secondary to the rupture of a vein, particularly if the middle meningeal vein or dural sinuses are involved.

Rarely, EDH can occur secondary to arteriovenous abnormalities or bleeding disorders.

Pathophysiology

As the volume of blood leaking from the damaged blood vessel into the extradural space increases, it begins to strip the outer layer of the meninges, the dura mater, away from the skull.

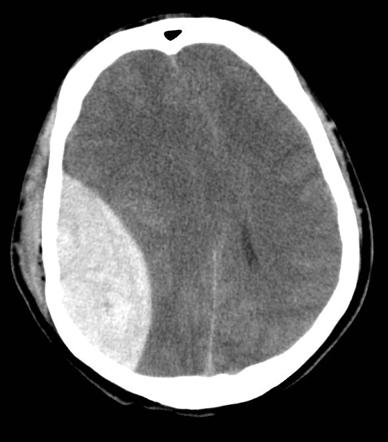

This often leads to the lemon-shaped haematoma, which is visible on CT and MRI imaging.

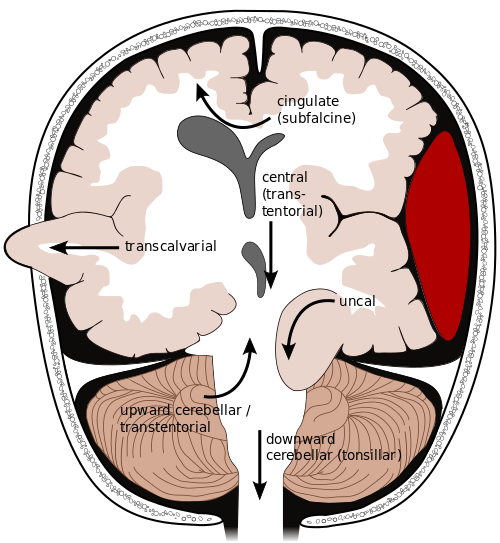

If the extradural haematoma continues to increase in size, the pressure inside the cranium (intracranial pressure) also increases. Without treatment, this increased pressure can cause damage to the brain through midline shift (displacement of the brain) and tentorial herniation (Figure 2).

A rising level of intracranial pressure (ICP) will eventually lead to brainstem death.

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of EDH include:

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Confusion

- Loss of consciousness (typically immediately after a head injury) followed by a period of lucidity

- Progressively decreasing level of consciousness (typically developing several hours after the initial injury)

Clinical examination

Patients with a traumatic head injury require a thorough neurological examination, including cranial nerves, upper limb and lower limb.

Typical clinical findings in EDH may include:

- Tenderness of the skull (in the context of injury)

- Confusion

- Reduced Glasgow Coma Score

- Cranial nerve deficits (e.g. oculomotor nerve palsy causing fixed dilation of the ipsilateral pupil)

- Motor or sensory deficits of the upper and/or lower limbs (e.g. hemiparesis, paraesthesia)

- Hyperreflexia and spasticity

- Upgoing plantar reflex (Babinski’s sign)

- Cushing’s triad: a physiological response to raised intracranial pressure including bradycardia, hypertension and deep/irregular breathing.

Cushing’s reflex

Cushing’s reflex is a physiological response to raised ICP to attempt to improve perfusion.

It leads to a triad of:

- Hypertension

- Bradycardia

- Irregular breathing pattern

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Capillary blood glucose: to rule out hypoglycaemia as a cause of reduced GCS

- ECG: to rule out heart block as a cause of bradycardia

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- FBC: to identify anaemia that may need correction

- U&Es: to rule out electrolyte abnormalities that may contribute to a reduced GCS

- CRP: if considering co-existing infection

- Coagulation: to rule out underlying coagulopathy

- Group and save: to allow transfusion of blood products, particularly relevant if the patient needs to go to theatre

Imaging

CT head

A CT head is the gold standard investigation in cases of suspected intracranial bleeding. This investigation should be requested urgently if intracranial bleeding is suspected.

The primary feature on a CT head in the context of EDH is a bi-convex “lemon-shaped” mass (rather than the typical “banana-shape” associated with subdural haemorrhages). This characteristic lemon shape develops due to the haematoma expanding medially due to being unable to expand past the points at which the dura is tightly bound to the suture lines of the skull.

Secondary features on a CT head can include midline shift and brainstem herniation, both of which are indications for early surgical intervention.

MRI head

MRI head has little benefit over CT and takes much longer to perform the scan, making it less ideal in the acute context.

MRI can be used in the sub-acute setting to assess for evidence of underlying cerebral contusions, ischaemia or diffuse axonal injury.

Skull X-ray

Skull X-ray is not typically used in the investigation of EDH however if a skull fracture is noted on a skull X-ray a CT head should be performed urgently to assess for evidence of EDH.

Cerebral angiography

Cerebral angiography may be used in the sub-acute setting to assess for an underlying arteriovenous malformation which may be the cause of the EDH (e.g. if there was no history of trauma).

Differential diagnoses

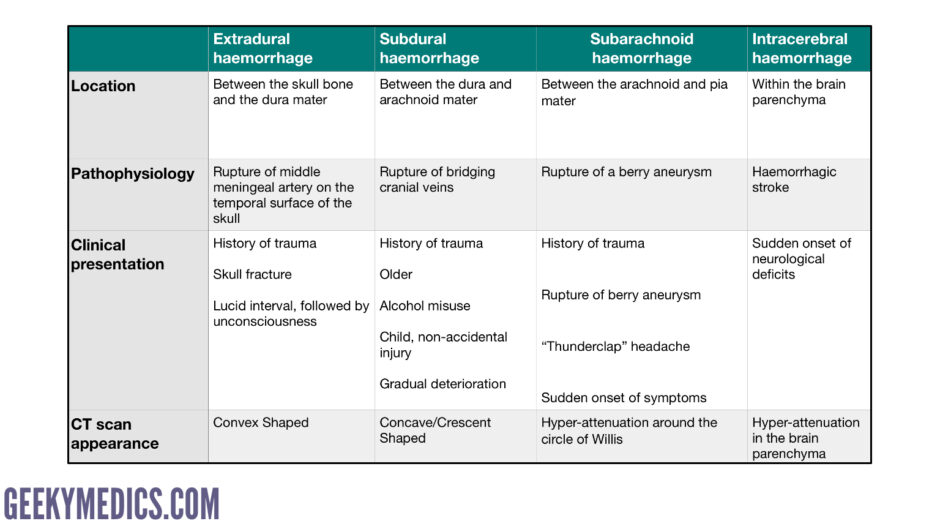

Sub-types of intracranial haemorrhage differ in their clinical presentation and radiological appearance.

The table below provides a brief summary of the different types of intracranial haemorrhage including their typical clinical features and appearance on CT.

Table 1. Types of intracranial bleeding

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to CT head interpretation.

Management

Initial management

Initial management of a patient with a suspected EDH should follow an ABCDE approach to ensure the patient is stable before considering further management options.

Correction of coagulation studies

All patients on anticoagulation (e.g. warfarin) will require reversal agents to prevent further bleeding and extension of the EDH. Local guidelines for anticoagulation should be followed, with input from haematology if required.

Patients who are found to have a coagulopathy (e.g. prolonged PT, thrombocytopenia) need to be discussed with haematology for advice on appropriate treatments (e.g. fresh-frozen plasma, platelet transfusion).

Antibiotics

Prophylactic antibiotics may be administered, particularly in the context of an open skull fracture to reduce the risk of intracranial infection.

Anticonvulsant medication

Patients presenting with acute EDH are at an increased risk of developing seizures and therefore may be temporarily commenced on anticonvulsant medication to prevent seizures (e.g. levetiracetam, phenytoin).

Agents to reduce ICP

Mannitol may be used intravenously to help temporarily decrease ICP (via an osmotic effect) prior to surgical management.

Barbiturates may be used to help reduce ICP and to protect the brain from anoxia.

Definitive management

The choice of definitive management differs depending on the location, age, size and clinical features of the bleed.

Conservative management may be appropriate if the bleed is very small with minimal mass effect (i.e. midline shift).

Burr hole craniotomy is often performed to manage acute EDH allowing evacuation of the haematoma.

A trauma craniotomy is typically used in the context of acute EDH with significant mass effect to both evacuate blood, treat the cause of bleeding (e.g. ligation of a vessel) and reduce intracranial pressure.

If there is a large bleed and/or a lot of associated cerebral oedema hemicraniectomy (also known as a decompressive craniectomy) may be performed in an attempt to prevent brain stem herniation and death due to rising intracranial pressure.

Post-operative management

Patients require close observation during the post-operative period, including regular neurological observations. The aim is to prevent any secondary insults (e.g. oedema, ischaemia or infection).

ICP monitoring and repeat CT scans are useful for detecting early signs of clinical deterioration.

Complications

Complications of EDH include:

- Infection: due to skull fracture or as a result of operative intervention

- Cerebral ischaemia: typically occurs adjacent to the haematoma

- Seizures

- Cognitive impairment

- Hemiparesis

- Hydrocephalus due to obstruction of the ventricles

- Brainstem injury: due to significantly raised ICP

Prognosis

Most patients with an extradural haematoma, even if large, have a good prognosis if they receive early evacuation of the haematoma. However, the prognosis worsens significantly if surgical intervention is delayed.

Clinical features associated with a poorer prognosis include:

- Low GCS at presentation

- No history of a lucid interval

- Pupil abnormalities

- Decerebrate rigidity

- Pre-existing brain injury

Key points

- Extradural haematoma (EDH) is defined as an acute haemorrhage between the dura mater and the inner surface of the skull.

- An extradural haematoma is most commonly caused by skull trauma in the temporoparietal region, typically following a fall, assault or sporting injury.

- Typical symptoms of EDH include headache, nausea/vomiting, confusion and reduced level of consciousness.

- Typical clinical signs of EDH include confusion, cranial nerve deficits, motor or sensory deficits of the limbs, hyperreflexia, spasticity, upgoing plantar reflex and Cushing’s triad.

- The key investigation in EDH is a CT head to identify the bleed and inform pre-operative planning.

- Management of EDH involves initially stabilising the patient followed by surgical intervention with a burr hole or craniotomy to evacuate the haematoma.

- The prognosis of EDH is good if treated rapidly but poor if surgical management is delayed.

- Complications include infection, cerebral ischaemia, seizures, hydrocephalus and hemiparesis.

Reviewer

Mr Konstantinos Lilimpakis

Neurosurgical Clinical Fellow

Editor

Samantha Strickland

Hull York Medical Student

References

- Mariana Ruiz Villarrea. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [Public domain]

- Rengachary SS (ed.), Ellenbogen RG (ed.). Principles of Neurosurgery, 2nd Edition. Elsevier; 2005

- Richard Millard. Brain herniation types. License: [CC-BY-SA]

- Extradural Haemorrhage. Case courtesy of Dr Sandeep Bhuta, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 4458.

- Hellerhoff. Epidural haematoma. License: [CC-BY-SA]

- Misulis KE, Head TC. Netter’s Concise Neurology, Updated Edition. Elsevier; 2017.

- Lindsay KW, Bone I, Fuller G. Neurology and Neurosurgery Illustrated, 5th Elsevier; 2011.

- Henry MM (ed.), Thompson JN (ed.). Clinical Surgery, 3rd Edition. Elsevier; 2012.