- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

GALS examination (gait, arms, legs and spine), is often used as a quick screening tool to detect locomotor abnormalities and functional disability in a patient. This GALS examination OSCE guide provides a clear step-by-step approach to performing the assessment, with an included video demonstration.

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language.

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Adequately expose the patient (ideally the patient should wear only shorts and undergarments).

Position the patient standing.

Screening questions

Part of the GALS assessment involves asking three screening questions to identify potential joint pathology, fine motor impairment and gross motor deficits.

Questions

First question

“Do you have any pain or stiffness in your muscles, joints or back?”

This question screens for common symptoms present in most forms of joint pathology (e.g. osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis).

Second question

“Do you have any difficulty getting yourself dressed without any help?”

This question screens for evidence of fine motor impairment and significant restriction joint range of movement.

Third question

“Do you have any problem going up and down the stairs?”

This question screens for evidence of impaired gross motor function (e.g. muscle wasting, lower motor neuron lesions) and general mobility issues (e.g. restricted range of movement in the joints of the lower limb).

Inspection

General inspection

Clinical signs

Perform a brief general inspection of the patient, looking for clinical signs suggestive of underlying pathology:

- Body habitus: obesity is a significant risk factor for joint pathology due to increased mechanical load (e.g. osteoarthritis).

- Scars: may provide clues regarding previous surgery.

- Wasting of muscles: suggestive of disuse atrophy secondary to joint pathology or a lower motor neuron injury.

- Psoriasis: typically presents with scaly salmon coloured plaques on extensor surfaces (associated with psoriatic arthritis).

Objects or equipment

Look for objects or equipment on or around the patient that may provide useful insights into their medical history and current clinical status:

- Aids and adaptations: examples include support slings, splints, walking aids and wheelchairs.

- Prescriptions: prescribing charts or personal prescriptions can provide useful information about the patient’s recent medications (e.g. analgesia).

Closer inspection

Ask the patient to stand in the anatomical position and turn in 90° increments as you inspect from each angle for evidence of pathology.

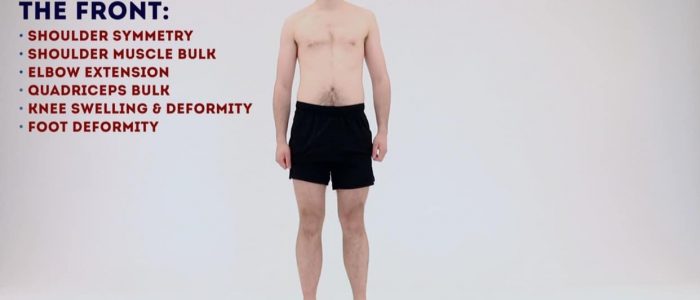

Anterior inspection

Inspect the patient from the front noting any abnormalities:

- Posture: note any asymmetry which may indicate joint pathology or scoliosis.

- Scars: note the location of any scars as they may provide clues as to the patient’s previous surgical history and/or indicate previous joint trauma.

- Joint swelling: note any evidence of asymmetry in the size of joints that may suggest unilateral swelling (e.g. effusion, inflammatory arthropathy, septic arthritis).

- Joint erythema: suggestive of active inflammation (e.g. inflammatory arthropathy or septic arthritis).

- Muscle bulk: note any asymmetry in upper and lower limb muscle bulk (e.g. deltoids, pectorals, biceps brachii, quadriceps femoris). Asymmetry may be caused by disuse atrophy (secondary to joint pathology) or lower motor neuron injury.

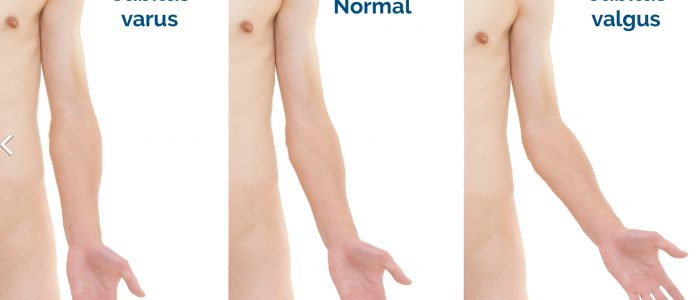

- Elbow extension: inspect the patient’s carrying angle which should be between 5-15°. An increased carrying angle is known as cubitus valgus. Cubitus valgus is typically associated with previous elbow joint trauma or congenital deformity (e.g. Turner’s syndrome). A decreased carrying angle is known as cubitus varus or ‘gunstock deformity’. Cubitus varus typically develops after supracondylar fracture of the humerus.

- Valgus joint deformity: the bone segment distal to the joint is angled laterally. In valgus deformity of the knee, the tibia is turned outward in relation to the femur, resulting in the knees ‘knocking’ together.

- Varus joint deformity: the bone segment distal to the joint is angled medially. In varus deformity of the knee, the tibia is turned inward in relation to the femur, resulting in a bowlegged appearance.

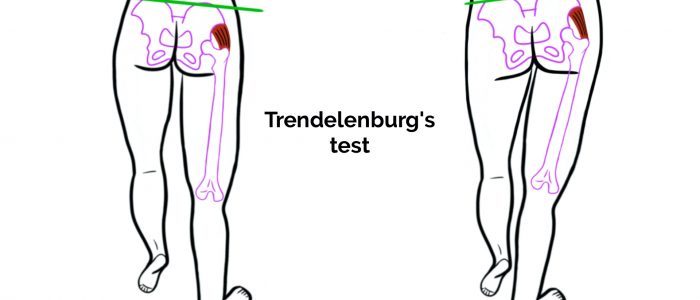

- Pelvic tilt: lateral pelvic tilt can be caused by scoliosis, leg length discrepancy or hip abductor weakness.

- Fixed flexion deformity of the toes: subtypes include hammer-toe and mallet-toe.

- Big toe: note any evidence of lateral (hallux valgus) or medial (hallux varus) angulation.

Lateral inspection

Inspect the patient from the side noting any abnormalities:

- Cervical lordosis: hyperlordosis is associated with chronic degenerative joint disease (e.g. osteoarthritis).

- Thoracic kyphosis: the normal amount of thoracic kyphosis is typically between 20-45º. Hyperkyphosis is associated with Scheuermann’s disease (congenital wedging of the vertebrae).

- Lumbar lordosis: loss of normal lumbar lordosis suggests sacroiliac joint disease (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis).

- Knee joint hyperextension: causes include ligamentous damage and hypermobility syndrome.

- Foot arch: inspect for evidence of flat feet (pes planus) or an abnormally raised foot arch (pes cavus).

Posterior inspection

Inspect the patient from the behind noting any abnormalities:

- Muscle bulk: note any asymmetry in upper and lower limb muscle bulk (e.g. deltoid, trapezius, triceps brachii, gluteal muscles, hamstrings, calves). Asymmetry may be caused by disuse atrophy (secondary to joint pathology) or lower motor neuron injury.

- Spinal alignment: inspect for lateral curvature of the spine suggestive of scoliosis.

- Iliac crest alignment: misalignment may indicate a leg length discrepancy or hip abductor weakness.

- Popliteal swellings: possible causes include a Baker’s cyst or popliteal aneurysm (typically pulsatile).

- Achilles’ tendon thickening: associated with Achilles’ tendonitis.

- Valgus joint deformity: the bone segment distal to the joint is angled laterally. In valgus deformity of the ankle, the foot is turned outward in relation to the tibia.

- Varus joint deformity: the bone segment distal to the joint is angled medially. In varus deformity of the ankle, the foot is turned inward in relation to the tibia.

Gait

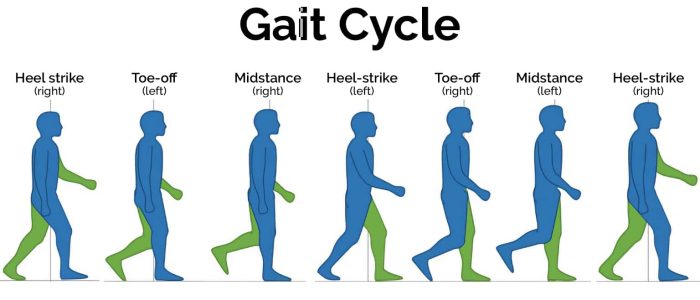

Ask the patient to walk to the end of the examination room and then turn and walk back whilst you observe their gait paying attention to:

- Gait cycle: note any abnormalities of the gait cycle (e.g. abnormalities in toe-off or heel strike).

- Range of movement: often reduced in the context of chronic joint pathology (e.g. osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis).

- Limping: may suggest joint pain (i.e. antalgic gait) or weakness.

- Leg length: note any discrepancy which may be the cause or the result of joint pathology.

- Turning: patients with joint disease may turn slowly due to restrictions in joint range of movement or instability.

- Trendelenburg’s gait: an abnormal gait caused by unilateral weakness of the hip abductor muscles secondary to a superior gluteal nerve lesion or L5 radiculopathy.

- Waddling gait: an abnormal gait caused by bilateral weakness of the hip abductor muscles, typically associated with myopathies (e.g. muscular dystrophy).

- Assess the patient’s footwear: unequal sole wearing is suggestive of an abnormal gait.

Gait cycle

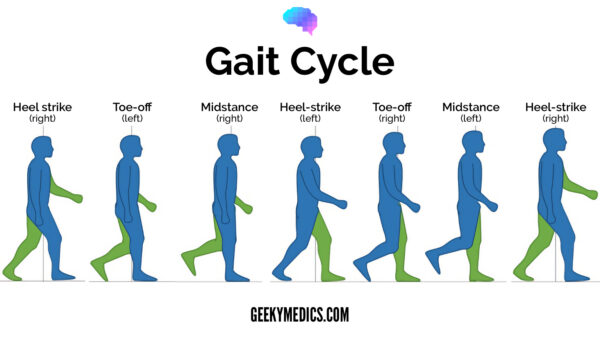

The gait cycle has six phases:

- Heel-strike: initial contact of the heel with the floor.

- Foot flat: weight is transferred onto this leg.

- Mid-stance: the weight is aligned and balanced on this leg.

- Heel-off: the heel lifts off the floor as the foot rises but the toes remain in contact with the floor.

- Toe-off: as the foot continues to rise the toes lift off the floor.

- Swing: the foot swings forward and comes back into contact with the floor with a heel strike (and the gait cycle repeats).

Arms

Compound movements

Hands behind head

Ask the patient to put their hands behind their head and point their elbows out to the side:

- This compound movement assesses shoulder abduction and external rotation in addition to elbow flexion.

- Restricted range of movement is suggestive of shoulder or elbow pathology (e.g. osteoarthritis).

- Excessive range of movement indicates hypermobility.

Hands held out in front with palms facing down

Ask the patient to hold their hands out in front of them, with their palms facing down and fingers outstretched:

- This compound movement assesses forward flexion of the shoulders, elbow extension, wrist extension and extension of the small joints of the fingers.

Inspect the dorsum the hands for asymmetry, joint swelling and deformity.

Inspect the nails for signs associated with psoriasis (e.g. nail pitting).

Hands held out in front with palms facing up

Ask the patient to turn their hands over (demonstrating supination):

- This compound movement assesses wrist and elbow supination.

- Restriction of supination is suggestive of wrist or elbow pathology (e.g. osteoarthritis).

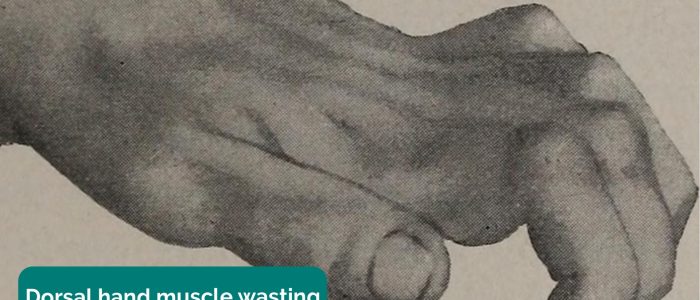

Inspect the thenar and hypothenar eminences for evidence of muscle wasting.

Making a fist

Ask the patient to make a fist whilst observing hand function:

- This movement assesses flexion of the small joints of the fingers as well as overall hand function.

- The patient may be unable to make a fist if they have joint swelling (e.g. inflammatory arthritis or joint infection) or if they have other deformities of the small joints of the hands.

Grip strength

Ask the patient to squeeze your fingers and assess grip strength (comparing the patient’s hands):

- Grip strength may be reduced due to pain (e.g. swelling of the small joints of the hand) or due to lower motor neuron lesions (e.g. median nerve damage secondary to carpal tunnel syndrome).

Precision grip

Ask the patient to touch each finger in turn to their thumb (known as ‘precision grip’):

- This sequence of movements assesses co-ordination of the small joints of the fingers and thumbs.

- Reduced manual dexterity may suggest inflammation or joint contractures of the small joints of the hand.

Metacarpophalangeal joint squeeze

Gently squeeze across the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints and observe for verbal and non-verbal signs of discomfort. Tenderness is suggestive of active inflammatory arthropathy.

Legs

Position the patient lying down on the examination couch for further assessment of the lower limbs.

Passive movement

Passive movement refers to a movement of the patient, controlled by the examiner. This involves the patient relaxing and allowing you to move the joint freely to assess the full range of joint movement. It’s important to feel for crepitus as you move the joint (which can be associated with osteoarthritis) and observe any discomfort or restriction in the joint’s range of movement.

Passive knee flexion

Normal range of movement: 0-140°

Instructions: Whilst supporting the patient’s leg, flex the knee as far as you are able, making sure to observe for signs of discomfort.

Passive knee extension

If the patient is able to lay their legs flat on the bed, they are already demonstrating a normal range of movement for knee extension. To assess for hyperextension:

1. On the leg being assessed, hold above the ankle joint and gently lift the leg upwards.

2. Inspect the knee joint for evidence of hyperextension, with less than 10° being considered normal. Excessive knee hyperextension may suggest pathology affecting the integrity of the knee joint’s ligaments or hypermobility.

Passive internal rotation of the hip

Normal range of movement: 40°

Instructions: Flex the patient’s hip and knee joint to 90° and then rotate their foot laterally.

Metatarsophalangeal joint squeeze

Gently squeeze across the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints and observe for verbal and non-verbal signs of discomfort. Tenderness is suggestive of active inflammatory arthropathy.

Patellar tap

Joint effusion can be caused by ligament rupture (e.g. anterior cruciate ligament), septic arthritis, inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis.

The patellar tap test can be used to screen for the presence of a moderate-to-large knee joint effusion.

1. With the patient’s knee fully extended, empty the suprapatellar pouch by sliding your left hand down the thigh to the upper border of the patella.

2. Keep your left hand in position and use your right hand to press downwards on the patella with your fingertips.

3. If there is fluid present you will feel a distinct tap as the patella bumps against the femur.

Spine

Ask the patient to stand upright for this part of the assessment. Inspection of the spine does not need to be repeated if already performed.

Cervical lateral flexion

Assess lateral flexion of the cervical spine by asking the patient to tilt their head to each side, moving their ear towards their shoulder: “Try and touch your shoulder to your ear on each side.”

Lumbar flexion

Assess the range of lumbar flexion using your fingers to palpate for a normal range of movement of the lumbar vertebrae (loss of lumbar flexion can be masked by good hip flexion, making inspection without palpation less reliable):

1. Place two of your fingers on the lumbar vertebrae approximately 5-10cm apart.

2. Ask the patient to bend forwards and touch their toes.

3. Observe your fingers as the patient’s lumbar spine flexes (they should move apart).

4. Observe your fingers as the patient extends their spine to return to a standing position (your fingers should move back together).

If the patient is able to place their hands flat on the floor it suggests joint hypermobility.

Temporomandibular joint

An adult GALS screen can include assessment of the temporomandibular joint (previously this was only tested in children as part of pGALS).

To assess the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) ask the patient to open their mouth wide and put three of their fingers into their mouth (demonstrate using your own fingers and mouth).

This manoeuvre assesses the temporomandibular joint’s range of movement and screens for deviation of jaw movement.

Restricted jaw opening may be due to temporomandibular joint disease.

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

Example summary

“Today I examined Mr Smith, a 32-year-old male. On general inspection, the patient appeared comfortable at rest, with no stigmata of musculoskeletal disease. There were no objects or medical equipment around the bed of relevance.

“Assessment of the patient’s gait, arms, legs and spine were unremarkable.”

“In summary, these findings are consistent with a normal GALS examination.”

“For completeness, I would like to perform the following further assessments and investigations.”

Further assessments and investigations

- A focused examination of joints with suspected pathology.

- Further imaging if indicated (e.g. X-ray and MRI).

Reviewer

Professor Helen Foster

Professor of Paediatric Rheumatology

Newcastle University, UK

Twitter: @NcleUniHFoster and @pmmonlineorg

References

- Siegertmarc. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Clavicular fracture repair. Licence: CC BY.

- James Heilman, MD. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Knee effusion. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Mikael Häggström. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Cubitus valgus and varus. Licence: CC0.

- BioMed Central. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Valgus deformity. Licence: CC BY.

- Heilstedt HA, Bacino CA. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Lateral pelvic tilt secondary to leg length discrepancy. Licence: CC BY.

- Richard Huber. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Hammer toe. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Lamiot. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Hallux valgus. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Gzzz. Adapted by Geeky medics. Hallux varus. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- James Heilman, MD. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Psoriasis plaque. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Benefros. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Pes cavus. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Weiss HR. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Scoliosis. Licence: CC BY.

- BoH. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

- James Heilman, MD. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Rheumatoid arthritis chronic changes. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Drahreg01. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Heberden’s nodes. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Davplast. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Bouchard’s nodes. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Alborz Fallah. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Boutonnière deformity. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Phoenix119. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Swan neck deformity. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- David Jones. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Rheumatoid arthritis. Licence: CC BY 2.0.

- CopperKettle. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Onycholysis. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- GEMalone. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Ganglion. Licence: CC BY.

- HenrykGerlach. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Carpal tunnel scars. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Frank C. Müller. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Dupuytren’s. Licence: CC BY-SA.