- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This hernia examination OSCE guide provides an overview of how to examine a hernia in the groin.

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language: “Today I need to perform an examination of the lump you are concerned about, which will involve me having a look and feel of the lump. It shouldn’t be painful, however, it might be a little uncomfortable. If at any point you are in pain or would like me to stop, just let me know. For this examination, I will need you to have your trousers and underwear off to allow me to assess the lump. If you feel uncomfortable at any point, let me know and we can stop the examination.”

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Explain the need for a chaperone: “One of the ward staff members will be present throughout the examination, acting as a chaperone, would that be ok?”

Adjust the head of the bed to a 45° angle and ask the patient to lay on the bed.

Adequately expose the patient’s abdomen and inguinal region for the examination. Offer a sheet to allow exposure only when required.

Ask the patient if they have any pain before proceeding with the clinical examination.

General inspection

Clinical signs

Inspect the patient from the end of the bed whilst at rest, looking for clinical signs suggestive of underlying pathology:

- Pain: if the patient appears uncomfortable, ask where the pain is and whether they are still happy for you to examine them.

- Obvious scars: these may provide clues regarding previous abdominal surgery and be closely associated with an incisional hernia.

- Abdominal distention: may indicate underlying bowel obstruction secondary to an incarcerated hernia.

- Pallor: a pale colour of the skin that can suggest underlying anaemia (e.g. gastrointestinal bleeding, malignancy).

- Cachexia: ongoing muscle loss that is not entirely reversed with nutritional supplementation. Cachexia is commonly associated with underlying malignancy (e.g. pancreatic/bowel/stomach cancer) and advanced liver failure.

- Hernias: may be visible from the end of the bed (e.g. umbilical/incisional hernia). Asking the patient to cough will usually cause hernias to become more pronounced.

Objects and equipment

Look for objects or equipment on or around the patient that may provide useful insights into their medical history and current clinical status:

- Stoma bag(s): note the location of the stoma bag(s) as this can provide clues as to the type of stoma (e.g. colostomies are typically located in the left iliac fossa, whereas ileostomies are usually located in the right iliac fossa). Parastomal hernias are a common complication of stoma formation.

- Surgical drains: note the location of the drain and the type/volume of the contents within the drain (e.g. blood, chyle, pus).

- Mobility aids: items such as wheelchairs and walking aids give an indication of the patient’s current mobility status.

Differentiating a hernia from other types of lumps

Begin by assessing the groin lump to determine if it is a hernia or some other type of pathology (e.g. testicular mass, lipoma, abscess, lymph node).

You should always assess both sides of the groin when assessing for hernias to avoid missing pathology.

Hernias of the groin typically present with the following clinical features:

- Single lump in the inguinal region

- Positive cough impulse (unless incarcerated)

- Soft on palpation

- Reducible (unless incarcerated)

- Unable to get above the lump during palpation

- Painless (unless incarcerated)

- Bowel sounds on auscultation (may be absent if incarcerated)

If any of the following clinical features are present, you should consider an alternative diagnosis:

- Multiple lumps (e.g. lymphadenopathy)

- Hard or nodular consistency (e.g. malignancy)

- Able to get above the lump during palpation (e.g. scrotal mass)

- Transillumination (hydrocoele)

- Bruit on auscultation (e.g. arteriovenous malformation)

Differentiating hernia subtypes

Position of the hernia

Assess the anatomical relationship of the hernia in relation to the pubic tubercle:

- Inguinal hernias are typically located above and medial to the pubic tubercle.

- Femoral hernias are typically located below and lateral to the pubic tubercle.

Reducibility

A reducible hernia is one which can be flattened out with changes in position (e.g. lying supine) or the application of pressure.

To assess the reducibility of a hernia:

1. Ask the patient to lay supine and observe for evidence of spontaneous reduction.

2. If the hernia is still present, try to manually reduce it using your fingers.

The hernia may re-appear if the patient stands up, coughs or the application of pressure is removed.

A hernia which is tender and irreducible may be strangulated and requires urgent surgical review.

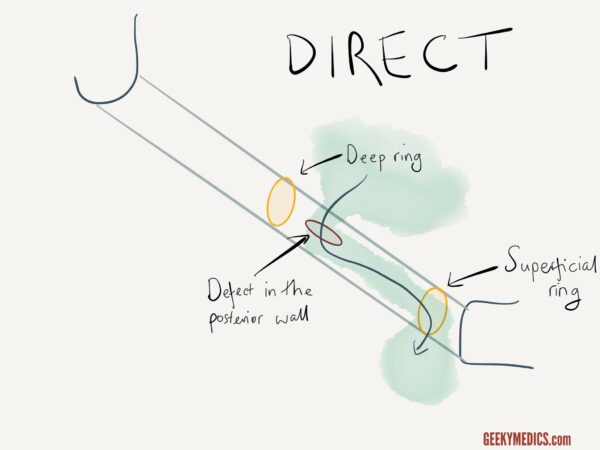

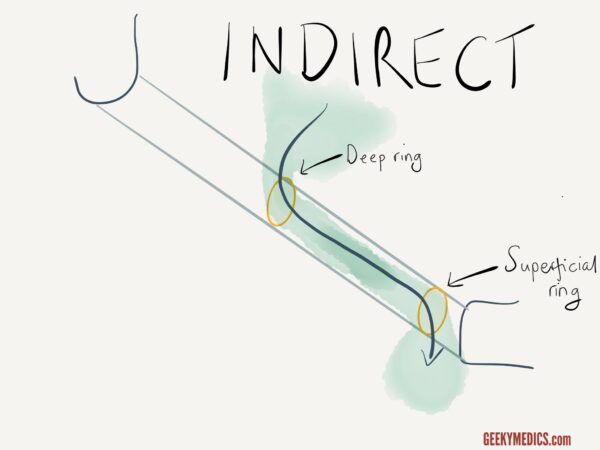

Direct vs indirect inguinal hernias

If you suspect a hernia is inguinal in origin (i.e. it is located above and medial to the pubic tubercle) you should then try to determine if it is direct or indirect.

To differentiate between direct and indirect inguinal hernias:

1. Locate the deep inguinal ring (midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic tubercle).

2. Manually reduce the patient’s hernia by compressing it towards the deep inguinal ring starting at the inferior aspect of the hernia.

3. Once the hernia is reduced, apply pressure over the deep inguinal ring and ask the patient to cough.

Interpretation

If a hernia reappears it is more likely to be a direct inguinal hernia whereas if it does not, it is more likely to be an indirect inguinal hernia.

In the latter case, release the pressure from the deep inguinal ring and observe for the hernia reappearing (further supporting the diagnosis of an indirect inguinal hernia).

It should be noted that this clinical test is unreliable and further imaging (e.g. ultrasound scan) would be required before any management decisions were made.

Hernia subtypes

An awareness of the various hernia subtypes their typical clinical features is essential when performing a hernia examination. We have summarised some important points below from our hernia overview article.

Inguinal hernias

An inguinal hernia is a protrusion, or movement of abdominal contents, from within the abdominal cavity. This tissue then protrudes, or emerges, at the exit point, the superficial inguinal ring.

Location: inguinal hernias are most commonly found superomedial to the pubic tubercle.

Femoral hernias

Femoral hernias occur just below the inguinal ligament when abdominal contents pass through a naturally occurring weakness in the abdominal wall called the femoral canal.

It is important to note that the femoral canal is narrow and is bordered medially by the sharp edge of the lacunar ligament. Therefore, femoral hernias are at higher risk of strangulation and obstruction.

Location: femoral hernias are typically found inferolateral to the pubic tubercle and medial to the femoral pulse.

Umbilical hernia

Umbilical hernias, as the name suggests, occur at the site of the umbilicus and are common. They can be large but are typically low risk for strangulation.

Location: umbilical region

Incisional hernia

Incisional hernias occur at the sites of previous operations where tissue integrity has been compromised.

Location: incisional hernias present as a bulge or protrusion at or near the site of a previous surgical incision.

Scrotal examination

Inguinal hernias can extend into the scrotum. If a testicular swelling is noted or there is suspicion of an inguinal hernia, palpation of the scrotum should be performed with the patient’s consent.

When palpating an inguinal hernia in the scrotum you will not be able to get above the mass.

See our testicular examination guide for more details.

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

Example summary

“Today I examined Mr Smith, a 64-year-old male. On general inspection, the patient appeared comfortable at rest, with no evidence of abdominal distension or discomfort. There were no objects or medical equipment around the bed of relevance.”

“Closer inspection revealed a mass visible in the left groin above and medial to the pubic tubercle. It was non-tender, approximately 2cm in diameter, soft in consistency and reducible. There was a positive cough impulse and the hernia recurred despite pressure over the deep inguinal ring. There was no extension to the scrotum and no associated lymphadenopathy.”

“The most likely diagnosis based on my clinical findings is a direct inguinal hernia.”

“For completeness, I would like to perform the following further assessments and investigations.”

Further assessments and investigations

- Testicular examination (if male and not already performed)

- Abdominal examination

- Inguinal lymph node assessment (if not already performed)

- Further imaging (e.g. ultrasound/CT)

References

- James Heilman, MD. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Inguinal hernia. Licence: CC BY 3.0.

- Milliways. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Umbilical hernia. Licence: CC BY-SA.