- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

A paediatric abdominal examination is often performed as part of the assessment of abdominal pain and/or distension. Care must always be taken to make sure no undue pain or discomfort is caused to the child. Rapport and trust can be lost very quickly and further examination might then be impossible.

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the parents and the child, including your name and role.

Confirm the child’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language: “Today I’d like to perform an examination of your child’s abdomen, which will involve first observing your child, then gently feeling their tummy.”

Gain consent from the parents/carers and/or child before proceeding: “Are you happy for me to carry out the examination?”

General inspection

Appearance and behaviour

Observe the child in their environment (e.g. waiting room, hospital bed) and take note of their appearance and behaviour:

- Activity/alertness: note if the child appears alert and engaged, or quiet and listless.

- Jaundice: a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the skin and whites of the eyes due to high bilirubin levels (e.g. breastfeeding related, hypothyroidism, rhesus factor disease).

- Pallor: a pale colour of the skin that can suggest underlying anaemia (e.g. gastrointestinal bleeding, malnutrition).

- Weight: note if the child appears a healthy weight for their age and height.

Syndromic features

Pay attention to features that may indicate the presence of an underlying genetic condition:

- Stature (e.g. tall/short)

- Syndromic facial features

See the end of this guide for a non-exhaustive list of clinical syndromes which can be associated with gastrointestinal system pathology.

Equipment

Observe for any equipment in the child’s immediate surroundings and consider why this might be relevant to the gastrointestinal system:

- NG/NJ tube: often used for bowel obstruction, short bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, gastroesophageal reflux, glycogen storage disorders, chronic liver disease, malignancy and anorexia.

- Gastrostomy: typically only used if an NG/NJ is needed for more than 6 weeks (indicative that the child has a chronic condition).

- Colostomy/ileostomy: often performed in the context of inflammatory bowel disease and malignancy.

- Intravenous lines/drip: suggests poor oral fluid intake.

- Special feeds: underlying intolerance, gastroesophageal reflux and malabsorption.

Medications

Note any medications by the bedside or in the child’s room and consider what underlying diagnoses they may indicate:

- Laxatives: constipation

- Antiemetics: nausea/vomiting

- Pancreatic enzymes: cystic fibrosis

Hands

The hands can provide lots of clinically relevant information and therefore a focused, structured assessment is essential.

Inspect the hands

General observations

Inspect the hands for clinical signs relevant to the gastrointestinal system:

- Pallor: may suggest underlying anaemia (e.g. malignancy, gastrointestinal bleeding, malnutrition).

- Peripheral oedema: associated with nephrotic syndrome (loss of albumin) and liver disease (reduced production of albumin).

Nail signs

Inspect the nails for any of the following signs:

- Koilonychia: spoon-shaped nails, associated with iron deficiency anaemia (e.g. malabsorption in Crohn’s disease).

- Leukonychia: whitening of the nail bed, associated with hypoalbuminaemia (e.g. nephrotic syndrome, protein-losing enteropathy).

Finger clubbing

Finger clubbing involves uniform soft tissue swelling of the terminal phalanx of a digit with subsequent loss of the normal angle between the nail and the nail bed. Finger clubbing is associated with several underlying disease processes, but those most likely to appear in an abdominal OSCE station include cystic fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease.

To assess for finger clubbing:

- Ask the child to copy you in placing the nails of their index fingers back to back.

- In a healthy individual, you should be able to observe a small diamond-shaped window (known as Schamroth’s window).

- When finger clubbing develops, this window is lost.

- If the child is too young for this to be possible, you can simply inspect the fingers, looking for soft tissue swelling of the terminal phalanx of the digits.

Pulse

Radial pulse

Palpate the child’s radial pulse, located at the radial side of the wrist, with the tips of your index and middle fingers aligned longitudinally over the course of the artery.

Once you have located the radial pulse, assess the rate and rhythm.

In babies, assess the femoral pulse instead.

Assessing heart rate

You can calculate the heart rate in a number of ways, including measuring for 60 seconds, measuring for 30 seconds and multiplying by 2 or measuring for 15 seconds and multiplying by 4.

For irregular rhythms, you should measure the pulse for a full 60 seconds to improve accuracy.

Face

Observe the child’s facial complexion and features, including their eyes and mouth.

General appearance

Inspect the general appearance of the child’s face for signs relevant to the gastrointestinal system:

- Oedema: associated with hypoalbuminaemia (e.g. protein-losing enteropathy, malnutrition, liver disease).

- Pallor: may suggest underlying anaemia (e.g. malignancy, gastrointestinal bleeding, malnutrition).

Eyes

Inspect the eyes for signs relevant to the gastrointestinal system:

- Conjunctival pallor: suggestive of underlying anaemia. Gently pull down their lower eyelid to inspect the conjunctiva.

- Scleral jaundice: a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the eyes due to high bilirubin levels (e.g. liver disease, hypothyroidism, rhesus factor disease).

- Aniridia (partial or complete absence of the coloured part of the eye): associated with WAGR syndrome which also involves the development of a Wilm’s tumour.

- Kayser-Fleischer rings: dark rings that encircle the iris associated with Wilson’s disease. The disease involves abnormal copper processing by the liver, resulting in accumulation and deposition in various tissues.

- Xanthelasma: yellow, raised cholesterol-rich deposits around the eyes associated with hypercholesterolaemia.

Mouth

Inspect the mouth for signs relevant to the gastrointestinal system (tip – ask the child to see how long their tongue is or how big their mouth is):

- Angular stomatitis: a common inflammatory condition affecting the corners of the mouth. It has a wide range of causes including iron deficiency.

- Glossitis: smooth erythematous enlargement of the tongue associated with iron, B12 and folate deficiency (e.g. malabsorption secondary to inflammatory bowel disease).

- Oral candidiasis: a fungal infection commonly associated with immunosuppression. It is characterised by pseudomembranous white slough which can be easily wiped away to reveal underlying erythematous mucosa.

- Aphthous ulceration: round or oval ulcers occurring on the mucous membranes inside the mouth. Aphthous ulcers are typically benign (e.g. due to stress or mechanical trauma), however, they can be associated with iron, B12 and folate deficiency as well as Crohn’s disease.

- Hyperpigmented macules: pathognomonic for Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, an autosomal dominant genetic disorder that results in the development of polyps in the gastrointestinal tract.

- Dental caries: may be associated with neglect or gastroesophageal reflux disease (acid erosion).

- Macroglossia: enlargement of the tongue associated with Down’s syndrome, hypothyroidism, mucopolysaccharidoses and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.

Neck

The left supraclavicular lymph node (known as Virchow’s node) receives lymphatic drainage from the abdominal cavity and therefore enlargement of Virchow’s node can be one of the first clinical signs of metastatic intrabdominal malignancy. The right supraclavicular lymph node receives lymphatic drainage from the thorax and therefore lymphadenopathy in this region can be associated with metastatic oesophageal cancer (as well as malignancy from other thoracic viscera).

Palpate for lymphadenopathy

Palpate the supraclavicular fossa on each side, paying particular attention to Virchow’s node on the left for evidence of lymphadenopathy.

Close inspection of the abdomen

Ask the parent or child (if appropriate) to expose the child’s abdomen.

Position the child lying flat on the bed, with their arms by their sides and legs uncrossed for abdominal inspection and subsequent palpation (this is often difficult to achieve in reality).

Inspect the child’s abdomen for signs suggestive of gastrointestinal pathology:

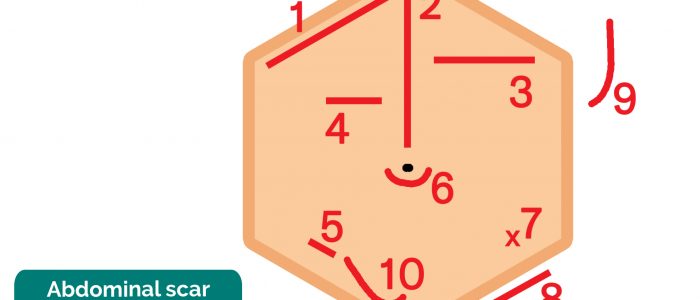

- Scars: there are many different types of abdominal scars that can provide clues as to the child’s past surgical history (see image below for examples).

- Abdominal distension: can be caused by a wide range of pathology including constipation, Hirschsprung’s disease, ascites, organomegaly and malignancy.

- Caput medusae: engorged paraumbilical veins associated with portal hypertension (e.g. liver cirrhosis).

- Hernias: observe for any protrusions through the abdominal wall (e.g. umbilical hernia, incisional hernia).

- Drains/tubes/stomas: gastrostomy, central venous catheter, ileostomy and colostomy.

Tip: The abdomen is normally protuberant in toddlers and young children.

Examples of scar locations

| Number | Incision type | Associated procedure |

| 1 | Kocher’s incision | Biliary surgery (e.g. cholecystectomy) Hepatic surgery |

| 2 | Midline laparotomy (variable length) | Fundoplication Major abdominal surgery |

| 3 | Transverse upper abdominal incision | Repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia Splenic surgery |

| 4 | Pyloromyotomy scar | Treatment of pyloric stenosis |

| 5 | Grid-Iron incision at McBurney’s point | Appendicectomy |

| 6 | Umbilical/sub-umbilical scars | Hernia repairs Gastroschisis repair Exomphalos |

| 7 | Point incision marks | Laparoscopy port sites Drain sites VP shunts |

| 8 | Inguinal incisions | Inguinal hernia repairs Vascular access scars |

| 9 | Lateral thoracolumbar incision | Renal surgery (nephrectomy) |

| 10 | ‘Hockey-Stick’ scar | Renal transplant |

Examining the abdomen

If appropriate, ask the child what they ate for their last meal and try to ‘find it’ (palpation). If you can’t ‘find it’, you’ll have to listen – leading you to auscultation (sneaky right?)

Preparing to palpate the abdomen

Before beginning abdominal palpation:

- Kneel down and/or raise the bed, your face is level with the child’s face.

- Use warm hands.

- Relax the child.

- Keep the parent close at hand.

- Abdominal wall muscles must be relaxed for palpation to be effective. Ensure the child is lying down entirely flat, with their hand by their sides. Take away any pillows or cushions.

- Expose the abdomen entirely, lowering the trousers and underwear whilst covering the child with a sheet.

Light palpation

Avoid mentioning to word “pain” or “hurt” (e.g. “Is this painful?” “Does that hurt?”) when examining young children, as this can often provoke fear and upset. Instead, observe the child’s body language and facial expressions to determine if they are in pain.

Perform light palpation of the nine abdominal regions, whilst looking at the child’s face and assessing for rigidity, tenderness, guarding and palpable masses.

Guarding is suggestive of peritonitis and indicates the need for urgent surgical review.

Deep palpation

Repeat palpation of the nine abdominal regions, this time applying greater pressure to better assess intra-abdominal structures (continue to observe the child’s face for signs of discomfort).

If any masses are identified, determine their location, approximate size, shape, consistency and mobility.

Tenderness

Localised in appendicitis (RIF), hepatitis (RUQ) and pyelonephritis (flank).

Generalised in mesenteric adenitis and peritonitis.

Guarding

Pain on coughing, moving about/walking/bumps during a car journey suggests peritoneal irritation.

A child walking, whilst being flexed forwards suggests psoas irritation (e.g. appendicitis).

Incorporating play may be used to elicit more subtle guarding:

- “Can you jump up and down?” – a child will not be able to jump on the spot if they have localised guarding.

- “Blow out your tummy as big as you can, then suck it in as far as you can” – this will elicit pain if there is peritoneal irritation.

Abnormal masses

Wilm’s tumour typically presents as a renal mass which is sometimes visible and does NOT cross the midline.

Neuroblastoma typically presents as an irregular firm mass which may cross the midline. The child is usually very unwell.

Faecal masses are typically mobile, non-tender, indentable and often located in the LIF.

Intussusception typically presents with a palpable mass in the RUQ (most commonly) in the context of an acutely unwell child.

Liver palpation and percussion

Palpate from the right iliac fossa and locate the edge of the liver with the tips or sides of your fingers (ask the child to take deep breaths if appropriate).

The liver edge may be soft or firm and you will be unable to get above it. The edge will move with respiration. Measure in centimetres the extension of the liver edge below the costal margin in the mid-clavicular line.

Percuss downwards from the right lung to exclude downward displacement due to lung hyperinflation (i.e. in bronchiolitis). Dullness to percussion can help delineate the upper and lower border. Record the span of the liver (in cm).

Tip: Young children may be more cooperative if you palpate first with their hand or by putting your hand on top of theirs.

Causes of hepatomegaly

There are several potential causes of hepatomegaly including:

- Infection: congenital, infectious mononucleosis, hepatitis, malaria

- Haematological: sickle cell anaemia, thalassaemia

- Malignancy: leukaemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, Wilm’s tumour, hepatoblastoma

- Metabolic: glycogen and lipid storage disorders, mucopolysaccharidoses

- Cardiovascular: heart failure

- Apparent hepatomegaly: chest hyper-expansion (e.g. bronchiolitis/asthma)

Splenic palpation and percussion

A palpable spleen is at least TWICE its normal size.

Palpate from the right iliac fossa towards the left upper quadrant (ask the child to take deep breaths if appropriate). The edge is usually soft and you will be unable to get above it. The splenic notch is occasionally palpable if markedly enlarged. The spleen should move with respiration.

Measure the degree of extension below the costal margin (in cm) in the mid-clavicular line.

Percuss to delineate the lower border (splenic tissue will be dull to percussion).

Causes of splenomegaly

There are several potential causes of splenomegaly including:

- Infection: infectious mononucleosis, malaria, leishmaniasis

- Haematological: haemolytic anaemia

- Malignancy: leukaemia, lymphoma

- Other: portal hypertension, Still’s disease

- Apparent splenomegaly: chest hyper-expansion (e.g. bronchiolitis/asthma)

Kidneys

The kidneys are not usually palpable beyond the neonatal period unless they are enlarged or the abdominal muscles are hypotonic.

Palpate the kidneys by balloting bi-manually in each hypochondrium. You can ‘get above them’ (unlike the spleen or liver) and tenderness implies inflammation.

Causes of kidney enlargement

- Unilaterally enlarged: hydronephrosis, cyst, tumour

- Bilaterally enlarged: hydronephrosis, kidney stones, polycystic kidneys

Ascites

Ascites may be present in cirrhosis, hypoalbuminaemia, infection or malignancy.

The presence of shifting dullness is highly suggestive of ascites.

Assessing for shifting dullness

It is usually not possible to formally assess for shifting dullness in young children, due to issues with co-operation. However, in older children, it may be possible.

1. Percuss from the umbilical region to the child’s left flank. If dullness is noted, this may suggest the presence of ascitic fluid in the flank.

2. Whilst keeping your fingers over the area at which the percussion note became dull, ask the child to roll onto their right side (towards you for stability).

3. Keep the child on their right side for 30 seconds and then repeat percussion over the same area.

4. If ascites is present, the area that was previously dull should now be resonant (i.e. the dullness has shifted).

Auscultation of the abdomen

Start by showing the child your stethoscope and demonstrate it on your own abdomen and/or on one of their toys to familiarise them with this piece of equipment.

Suggest listening to their abdomen, making sure the stethoscope diaphragm isn’t cold prior to it making contact with the child.

Auscultate over at least two positions on the abdomen to assess bowel sounds:

- Normal bowel sounds: typically described as gurgling.

- Tinkling bowel sounds: typically associated with bowel obstruction.

- Absent bowel sounds: suggests ileus which is a disruption of the normal propulsive ability of the intestine due to a malfunction of peristalsis. Causes of ileus include electrolyte abnormalities and recent abdominal surgery. To be able to confidently state that a child has ‘absent bowel sounds’ you need to auscultate for at least 3 minutes (this is unlikely to be the case in an OSCE given the time restraints).

Genital examination

A genital examination is often performed routinely in infants and young children, however in older children or teenagers it should only be performed if relevant (i.e. vaginal discharge, suspicion of inguinal hernia or perineal rash).

Male genital examination

Inspect the genitals to assess penile and scrotal development and to identify any abnormalities:

- Assess for penile abnormalities: hypospadias, chordee

- Assess for descended tests: with one hand over the inguinal region, palpate the testicles with the other hand (record if testis descended, retractile or impalpable).

- Note any scrotal swelling: hydrocele, hernia

Female genital examination

Inspect the external genitalia to identify any abnormalities:

- Abnormal discharge: may be associated with pelvic inflammatory disease.

Rectal examination

Not routinely performed and if indicated, it should be performed by a specialist who has experience interpreting findings.

The rectum may be inspected to identify relevant abnormalities:

- Imperforate anus

- Anal skin tags (Crohn’s)

- Anal prolapse

- Staining of underwear (may suggest constipation)

Lower limbs

Inspect for pedal oedema: associated with nephrotic syndrome and liver disease.

To complete the examination…

Explain to the child and parents that the examination is now finished.

Ensure the child is re-dressed after the examination.

Thank the child and parents for their time.

Explain your findings to the parents.

Ask if the parents and child (if appropriate) have any questions.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings to the examiner.

Further assessments and investigations

Suggest further assessments and investigations to the examiner:

- Nutritional assessment

- Examination of hernial orifices

- Pelvic examination in female adolescents if indicated

- Vital signs

- Measure and plot height and weight on a growth chart.

- Urinalysis: if urinary tract infection or nephrotic syndrome is suspected.

- Stool analysis: to identify infective organisms and evidence of inflammation (e.g. faecal calprotectin).

Syndromes that may impact the gastrointestinal system

| Syndrome | Clinical features |

|

Down’s syndrome Down syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21. |

Epicanthic folds Brushfield spots Protruding tongue Low set ears Duodenal atresia Hirschsprungs disease |

|

Turner syndrome Caused by loss of part or all of an X chromosome, affecting only females. |

Short stature Delayed puberty Webbed neck Shield chest Horseshoe kidney |

|

Williams syndrome Caused by the deletion of genetic material from a specific region of chromosome 7. |

Short palpebral fissures Upturned nose Cupid bow lip Nephrocalcinosis |

|

Alagille syndrome In 90 percent of cases, caused by mutations in the JAG1 gene. |

Broad forehead Small chin Flat face Biliary atresia Jaundice |

|

Thalassaemia A group of disorders in which the normal ratio of alpha-globin to beta-globin production is disrupted due to a disease-causing variant in one or more of the globin genes. |

Enlarged cheekbones Enlarged forehead Bone deformity Massive splenomegaly |

|

Glycogen storage disorder A glycogen storage disease is a metabolic disorder caused by enzyme deficiencies affecting either glycogen synthesis, glycogen breakdown or glycolysis, typically in muscles and/or liver cells. |

Myopathy/weakness Hepatosplenomegaly |

|

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome An overgrowth disorder involving a predisposition to tumour development. |

Hemi-hypertrophy Macroglossia Omphalocele Wilms’ tumour Kidney anomalies |

Reviewer

Dr Sunil Bhopal

Senior Paediatric Registrar

References

Text references

- Lissauer, T., Clayden, G., & Craft, A. (2012). Illustrated textbook of paediatrics. Edinburgh: Mosby.

- Miin Lee & Fawbert (2014). Abdominal Examination Guide. MRCPCH Clinical Revision. Trainees Committee, London School of Paediatrics [LINK] (Accessed 22 Mar 2019)

- Paeds.co.uk (2009) Surgical Scars – Abdomen. Paeds.co.uk the online paediatrician’s encyclopaedia.

- Tasker, R. C., McClure, R. J. & Acerini, C. L. (2013). Oxford handbook of paediatrics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Image references

- Jim Champion. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Nasogastric tube. Licence: CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. CHeitz. Koilonychia. Licence: CC BY 2.0.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. BrotherLongLegs. Leukonychia. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Desherinka. Finger clubbing. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Nephrotic syndrome. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Sheila J. Toro. Scleral jaundice. Licence: CC BY 4.0.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Herbert L. Fred, MD, Hendrik A. van Dijk. Kayser-Fleischer ring. Licence: CC BY 3.0.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Klaus D. Peter, Gummersbach, Germany. Xanthelasma. Licence: CC BY 3.0 DE.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Matthew Ferguson. Angular stomatitis. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Klaus D. Peter, Gummersbach. Glossitis. Licence: Klaus D. Peter, Gummersbach, Germany. Licence: CC BY 3.0 DE.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. James Heilman, MD. Oral candidiasis. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Abdullah Sarhan. Peutz-Jager syndrome. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Anandselvam85. Hepatomegaly. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. Stefania Leoni, Dora Buonfrate, Andrea Angheben, Federico Gobbi, Zeno Bisoffi. Splenomegaly. Licence: CC BY 4.0.

- Adapted by Geeky Medics. James Heilman, MD. Pedal oedema. Licence: CC BY-SA.