- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Common hip symptoms in children include pain in the hip or a limp. However, some children may have difficulty localising the pain and thus complain of pain in their groin, knee or leg.1

In all patients, a thorough history and examination of the hip should be undertaken.

This article will provide an overview of the anatomy of the hip and the common paediatric hip disorders.

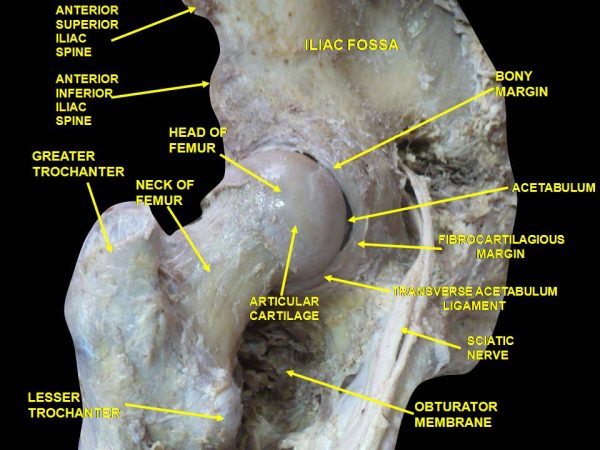

Anatomy of the hip

The hip is a ball-in-socket joint that provides the movements of flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation and circumduction.

The head of the femur sits in the acetabulum, joined centrally by the ligamentum teres (ligament of the head of the femur), carrying the acetabular branch of the obturator artery.

The acetabular fossa is lined by the acetabular labrum, joined inferiorly by the transverse acetabular ligament. Surrounding these structures is the synovial joint capsule (Figure 1).

Three external ligaments support the hip, the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral and pubofemoral ligaments. These are named respectively for the part of the hip bone from which they originate, and their insertion into the femur.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

DDH is a disorder of abnormal development resulting in dysplasia and potential subluxation or dislocation of the hip secondary to capsular laxity and mechanical factors.4,5

DDH is the most common abnormality in newborn infants. Due to the nature of how the baby sits in the womb, the left hip is more commonly affected.4,5

Risk factors

The exact cause of DDH is unknown but risk factors for DDH include:

- Family history of DDH

- Breeched baby

- Female sex

- Fixed foot deformity

- Torticollis

There is no singular way to prevent DDH. The incidence of DDH may be influenced by local child-rearing practices, as certain swaddling and baby-carrying techniques have been shown to correlate with a decline in this disorder.6

Clinical features

If DDH is suspected, an examination of the hip should be undertaken. In addition, screening examinations are performed as part of routine baby checks.

Findings in 3-6-month-olds include leg length discrepancy and limitations in hip abduction due to contractures.

In older children (> 1 year), a Trendelenburg gait and toe walking may also be seen.

Further clinical findings at any age may include:

- Asymmetrical buttock creases

- Hip locking/clicking

- Pain

The Ortolani and Barlow tests are used to screen babies for hip dysplasia.

Ortolani and Barlow tests

Barlow’s test is performed by adducting the hip (bringing the thigh towards the midline) whilst applying light pressure on the knee with your thumb, directing the force posteriorly.

If the hip is unstable, the femoral head will slip over the posterior rim of the acetabulum, producing a palpable sensation of subluxation or dislocation.

If the hip is dislocatable the test is considered positive.

Ortolani’s test is then used to confirm posterior dislocation of the hip joint.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to performing a newborn baby assessment.

Investigations

Relevant investigations include:

- Ultrasound: can be performed in infants less than 4-6months old

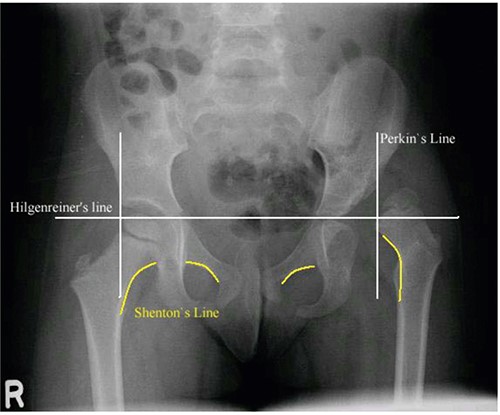

- AP pelvic X-ray: should be performed in children greater than 4-6months old, when the femoral head ossification centre is visible (Figure 3)

Management

Management of DDH depends on the age of the patient:7

- Under 6 months: Pavlik harness

- 6 – 18 months (or failure of Pavlik harness): closed reduction and spica casting

- Greater than 18 months (or failure of closed reduction): operative management (open reduction and hip reconstruction)

Complications

Complications of DDH include:

- Recurrence

- Transient femoral nerve palsy with excessive flexion during Pavlik bracing

- Avascular necrosis: due to retrograde femoral head blood flow. Most commonly affects the median circumflex femoral artery.

Legg-Calve-Perthes disease

Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (also called Perthes disease) causes idiopathic avascular necrosis of proximal femoral epiphysis in children.7

Epidemiology

In the United Kingdom, the incidence of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease is 7.8 per 100,000 children aged 0-14.10

Risk factors

The exact cause is unknown, risk factors include:

- Age 4-10

- Male

- Family history

- Caucasian

Clinical features

Clinical examination findings may include:

- Limp (can be painless)

- Hip stiffness with loss of internal rotation and abduction

- Pain

- Antalgic gait

- Muscle spasms

- Leg length discrepancy (late finding)

Investigations

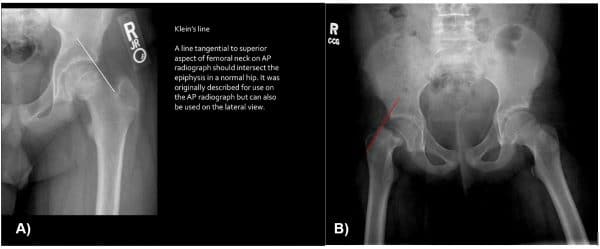

A bilateral AP pelvic x-ray and ‘frog-leg’ lateral X-ray are used to diagnose Perthes disease (Figure 5).

A bone scan or MRI may be useful if the diagnosis is unclear. They can also provide information on the extent of femoral head involvement.

Radiographic findings

Key radiographic signs of Perthes disease include:11

- Asymmetrical femoral epiphyseal size

- Increased density of femoral head epiphysis

- Radiolucency

- Coxa plana: femoral head widening and flatting (shown in Figure 4)

- Coxa magna: proximal femoral neck deformity

- ‘Sagging rope sign’: thin sclerotic line running across the femoral neck

*Crescent’s sign is a specific finding on a radiograph in late stages of the disease and represents a subchondral fracture.

Management

Conservative

Conservative management options include:

- Observation

- Activity limitation

- Physiotherapy

- Analgesia: NSAIDs

- Casting and bracing

Surgical

Surgery (osteotomy) is considered, based on the patient’s age, radiographic findings and clinical features.

The following would increase the likelihood of the need for surgical intervention:9

- Age over eight years old

- More than 50% of the femoral head is damaged

- Nonsurgical management has been unsuccessful

Complications

Complications of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease include:12

- Osteoarthritis

- General joint stiffness and immobility

- Premature physeal arrest, degenerative arthritis

- Acetabular dysplasia

- Unequal, shortened limb length

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE)

SCFE occurs when the metaphysis of the femur displaces anteriorly and superiorly, leading to the displacement of the capital femoral epiphysis.13

SCFE is the most common hip disorder in adolescents.14

Risk factors

The exact cause of SCFE is unknown but risk factors include:

- Male

- Obesity: increases stress on physis

- Puberty/endocrine disorders: hormones weaken physis, making it more prone to displacement

- Previous radiotherapy

Clinical features

Clinical features of SCFE include:

- Pain

- Abnormal leg alignment: external rotation

- Abnormal gait/limp: may have Trendelenburg gait

- Decreased range of movement

- Weakness and muscle atrophy

Investigations

SCFE is diagnosed by obtaining bilateral AP pelvic x-rays, along with a frog-leg lateral X-ray (Figure 5).

Thyroid function tests or growth hormone may be considered in the presence of a conjunctive endocrine disorder.

Management

Management of SCFE is usually surgical.

Options include:

- In situ fixation of the epiphysis with a screw

- Bone graft epiphysiodesis

- Spica cast

- In situ fixation with multiple pins

Complications

Complications of SCFE include:15

- Chondrolysis

- Late deformity

- SCFE in the contralateral hip

- Osteonecrosis

- Infection

- Chronic pain

- Degenerative arthritis

- Pin associated fracture

Transient synovitis

Transient synovitis is an intermittent inflammatory disorder of the synovium of the hip, common in paediatric populations.18

Up to three percent of children have an episode of transient synovitis at some point during their life.18

Risk factors

The exact cause of transient synovitis is unknown. However, many children develop the disease secondary to a viral upper respiratory infection.

Clinical features

Clinical features of transient synovitis include:

- Hip presents in flexion, abduction and external rotation

- Limited range of motion: most commonly, hip abduction

- Limp

- Pain

- Muscle spasms

Investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: raised white cell count

- Inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR): will be raised

Relevant imaging investigations include:

- AP, lateral or frog-leg X-ray to rule out other paediatric hip disorders

- Ultrasound can be performed if there is suspicion of septic arthritis

The most important differential diagnosis to rule out is septic arthritis. Therefore, always review Kocher’s criteria and perform an ultrasound if there is clinical suspicion of this severe pathological process.19

Management

Transient synovitis is a self-limiting disorder that typically lasts 7-10 days, therefore management is focused on relieving the patient’s symptoms:

- Bed rest (short period)

- Activity restriction

- Analgesia: paracetamol and NSAIDs.

Complications

There are rarely any complications of transient synovitis.

Summary

Conditions by age

The signs and symptoms of the various paediatric hip disorders often overlap. It is beneficial to think about each condition in the context of the age range most commonly affected:20

- Age 0 – 4: DDH

- Age 4 – 10: Perthes disease, transient synovitis

- Age 10 – 16: SCFE

Summary table

Table 1. Summary of common paediatric hip disorders

| Condition | Risk factors | Investigations | Management |

| DDH |

|

|

|

| Perthes |

|

|

|

| SCFE |

|

|

|

| Transient synovitis |

|

|

|

Reviewer

Miss Kirsty MacLeod

Orthopaedic Registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Krula M, van der Woudena JC, Schellevis FG, van Suijlekom-Smitd LWA, Koesa BW. Acute non-traumatic hip pathology in children: Incidence and presentation in family practice. Fam Pract. 2009;27(2):166–70.

- Anatomist90. Anatomical dissection. License: [CC-BY-SA]

- WikiRadiology. Pelvis Radiographic Anatomy. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- International Hip Dysplasia Institute .Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH). Published in 2018 Available from: [LINK]

- Brainscape. DDH (Developmental Dysplasia of Hip) Flashcards. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Loder RT, Skopelja EN. The Epidemiology and Demographics of Hip Dysplasia. ISRN Orthop. 2011;2011:1–46. Available from: [LINK]

- Souder C. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Noordin S, Umer M, Hafeez K, Nawaz H. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2010;2(2):19. Available from: [LINK]

- OrthoInfo. Perthes Disease. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Perry DC, Bruce CE, Pope D, Dangerfield P, Platt MJ, Hall AJ. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in the UK: Geographic and temporal trends in incidence reflecting differences in degree of deprivation in childhood. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(5):1673–9.

- Matt Skalsi FG et al. Perthes Disease Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Souder C. Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease. Available from: [LINK]

- Loder RT / BMJ Best Practice. Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. BMJ Best Practice. 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Peck D. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: Diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(3):258–62.

- Bassett A. Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. Available from: [LINK]

- The Orthopaedic Knowledge Network. Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- WikiDoc. Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. Available from: [LINK]

- James McCarthy JD / BMJ Best Practice. Transient synovitis of the hip. Available from: [LINK]

- Evan Watts ES. Transient Synovitis of Hip . Available from: [LINK]

- Radiology Assistant. Hip pathology in children. Available from: [LINK]