- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

What is SIADH?

The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) is characterised by excessive secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the posterior pituitary gland or another source.

ADH controls water reabsorption via its effect on kidney nephrons, causing the retention of water (but not the retention of solutes). By increasing water retention, ADH assists in the dilution of the blood, decreasing the concentration of solutes such as sodium.

Physiology

Normal physiology

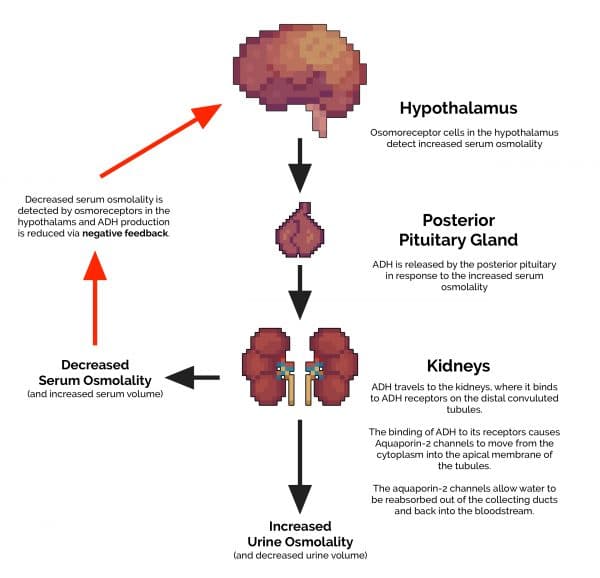

1. ADH (also known as vasopressin) is produced by the hypothalamus in response to increased serum osmolality.

2. ADH is transported from the hypothalamus to the posterior pituitary gland.

3. ADH is released into the circulatory system via the posterior pituitary gland.

4. ADH then travels to the kidneys, where it binds to ADH receptors on the distal convoluted tubules.

5. The binding of ADH to these receptors causes aquaporin-2 channels to move from the cytoplasm, into the apical membrane of the tubules. These aquaporin-2 channels allow water to be reabsorbed out of the collecting ducts and back into the bloodstream. This results in both a decrease in volume and an increase in osmolality (concentration) of the urine excreted.

6. The extra water that has been reabsorbed re-enters the circulatory system, reducing the serum osmolality.

7. This reduction in serum osmolality is detected by the hypothalamus and results in decreased production of ADH.

Deranged physiology in SIADH

The critical difference between normal physiology and what occurs in SIADH is the lack of an effective negative feedback mechanism. This results in continual ADH production, independent of serum osmolality.

Ultimately, this leads to abnormally low serum sodium levels and relatively high urinary sodium levels, giving rise to the characteristic clinical features associated with SIADH.

What causes SIADH?

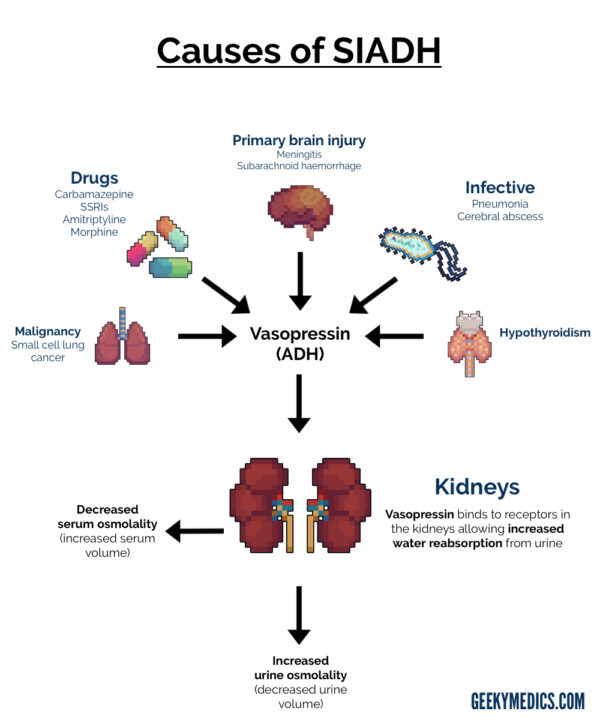

There are lots of potential causes of SIADH, including:

- Primary brain injury (e.g. meningitis, subarachnoid haemorrhage)

- Malignancy (e.g. small-cell lung cancer)

- Drugs (e.g. carbamazepine, SSRIs, amitriptyline)

- Infectious (e.g. atypical pneumonia, cerebral abscess)

- Hypothyroidism

Clinical features

History

The symptoms of SIADH vary depending upon both the severity of the hyponatraemia and the rate at which it develops:

- Mild hyponatraemia: nausea, vomiting, headache, anorexia and lethargy.

- Moderate hyponatraemia: muscle cramps, weakness, confusion and ataxia.

- Severe hyponatraemia: drowsiness, seizures and coma.

Mild hyponatraemia may cause significant symptoms if the drop in sodium is acute, whereas chronically hyponatraemic patients may have very low serum sodium concentrations and yet be asymptomatic.

This is thought to be due to a compensatory process known as cerebral adaptation, in which brain cells adapt their metabolism to cope with abnormal sodium levels. Cerebral adaptation can only occur if the change in sodium concentration is gradual, explaining the more severe symptoms associated with acute hyponatraemia and the potentially less severe symptoms associated with chronic hyponatraemia.1

Clinical examination

The clinical signs of SIADH can also vary significantly, depending on the rate of serum sodium concentration change.

Clinical signs of SIADH can include:2

- Decreased level of consciousness

- Cognitive impairment: short-term memory loss, disorientation and confusion

- Focal or generalised seizures

- Brain stem herniation (severe acute hyponatraemia) results in coma and respiratory arrest

- Hypervolaemia: pulmonary oedema, peripheral oedema, raised jugular venous pressure and ascites

Fluid status assessment

A fluid/hydration status assessment is vital in any patient with hyponatraemia:

- Patients with SIADH are typically euvolemic or hypervolaemic (i.e. not dehydrated)

- If dehydration is present, it may suggest an alternative cause for the hyponatraemia (e.g. diuretic-related renal failure)

Investigations

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Urea & electrolytes: serum sodium is low in SIADH (<130 mmol/L).

- Plasma osmolality: reduced in SIADH (due to low serum sodium).

- Thyroid function tests (TFTs): hypothyroidism is a potential cause of SIADH.

- Serum cortisol: should be checked to rule out Addison’s disease as a cause of hyponatraemia (cortisol is reduced in Addison’s disease).

Urine tests

Urine osmolality: in healthy individuals, if serum osmolality is low, urine osmolality should also be low, as the kidneys should be working hard to retain solute. In SIADH, excess ADH results in water retention but not solute retention. As a result, concentrated urine (which is relatively high in sodium) is produced despite low serum sodium.

Urine sodium: raised in SIADH despite low serum sodium concentration.

Imaging

Chest X-ray and/or CT-chest: used to rule out causes of SIADH (e.g. small cell lung cancer, atypical pneumonia).

Diagnosis

The following features must be present for a diagnosis of SIADH to be established: ³

- Hyponatraemia

- Low plasma osmolality

- Inappropriately elevated urine osmolality (i.e. greater than plasma osmolality)

- Urine [Na+] >40 mmol/L despite normal salt intake

- Euvolaemia

- Normal thyroid and adrenal function

Management

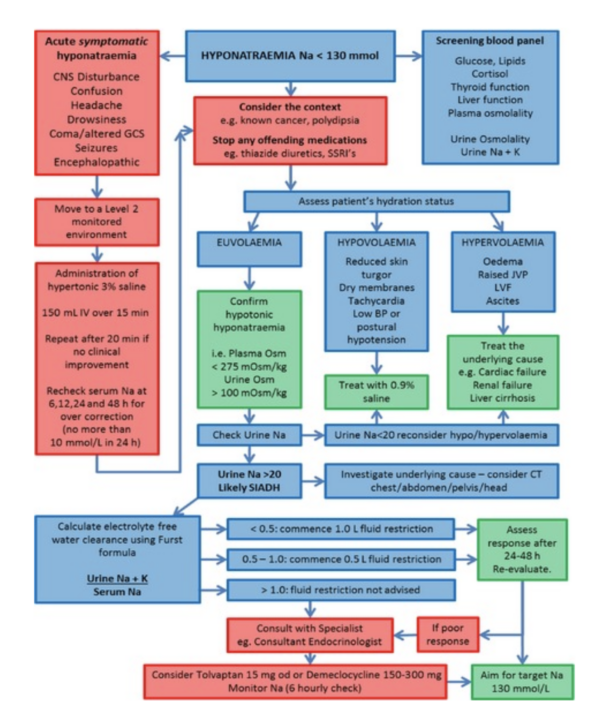

Management of SIADH varies depending on the underlying cause. Definitive management involves treating the underlying cause of SIADH.

Fluid restriction

Fluid restriction is a common management strategy used to increase serum sodium concentrations, at least temporarily, whilst the underlying cause is sought and treated. This strategy greatly depends on patients cooperating with the treatment plan, as fluid restriction can be challenging for patients.

The management algorithm below provides an overview of the current guidelines on the management of SIADH.3

References

- Craig S; Hyponatremia in Emergency Medicine, Medscape, Published Apr 2010.

- Robert D. Zenenberg, Do, et. al (2010-04-27). “Hyponatremia: Evaluation and Management”. Hospital Practice. 38 (1): 89–96

- Grant P, Ayuk J, Bouloux PM, et al; The diagnosis and management of inpatient hyponatraemia and SIADH. Eur J Clin Invest. 2015 Aug45(8):888-94. doi: 10.1111/eci.12465. Epub 2015 Jun 28. Available from: [LINK]