- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Thyroid status examination frequently appears in OSCEs and you’ll be expected to pick up the relevant clinical signs using your examination skills. This thyroid status examination OSCE guide provides a clear step-by-step approach to assessing thyroid status, with an included video demonstration.

Thyroid hormone (T3)

Gather equipment

- Stethoscope

- Glass of water

- Tendon hammer

- Piece of paper

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language.

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Ask the patient to sit on a chair for the assessment.

Adequately expose the patient’s neck and upper sternum.

Ask the patient if they have any pain before proceeding with the clinical examination.

General inspection

Clinical signs

Inspect the patient, looking for clinical signs suggestive of underlying pathology:

- Weight: weight loss is typically associated with hyperthyroidism (increased metabolism), whilst weight gain is associated with hypothyroidism (decreased metabolism).

- Behaviour: anxiety and hyperactivity are associated with hyperthyroidism (due to sympathetic overactivity). Hypothyroidism is more likely to be associated with low mood.

- Clothing: may be inappropriate for the current temperature. Patients with hyperthyroidism suffer from heat intolerance whilst patients with hypothyroidism experience cold intolerance.

- Hoarse voice: caused by compression of the larynx due to thyroid gland enlargement (e.g. thyroid malignancy).

Objects and equipment

Look for objects or equipment on or around the patient that may provide useful insights into their medical history and current clinical status:

- Mobility aids: patients with hyperthyroidism can develop proximal myopathy.

- Prescriptions: prescribing charts or personal prescriptions can provide useful information about the patient’s recent medications (e.g. levothyroxine).

Hands

Inspection

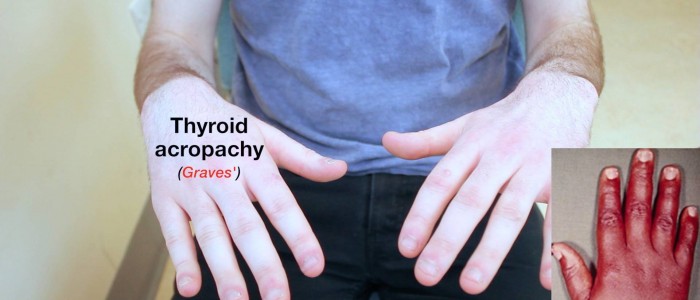

Inspect the patient’s hands for peripheral stigmata of thyroid-related pathology:

- Thyroid acropachy: similar in appearance to finger clubbing but caused by periosteal phalangeal bone overgrowth secondary to Graves’ disease.

- Onycholysis: painless detachment of the nail from the nail bed associated with hyperthyroidism.

- Palmar erythema: reddening of the palms associated with hyperthyroidism, chronic liver disease and pregnancy.

Peripheral tremor

Peripheral tremor is a feature of hyperthyroidism reflecting sympathetic nervous system overactivity.

To assess for evidence of a subtle peripheral tremor:

1. Ask the patient to stretch their arms out in front of them.

2. Place a piece of paper across the back of the patient’s hands.

3. Observe for evidence of a peripheral tremor (the paper will quiver).

Radial pulse

Palpate the patient’s radial pulse, located at the radial side of the wrist, with the tips of your index and middle fingers aligned longitudinally over the course of the artery.

Once you have located the radial pulse, assess the rate and rhythm.

You can calculate the heart rate in a number of ways, including measuring for 60 seconds, measuring for 30 seconds and multiplying by 2 or measuring for 15 seconds and multiplying by 4.

For irregular rhythms, you should measure the pulse for a full 60 seconds to improve accuracy.

Abnormal heart rates and rhythms

- In healthy adults, the pulse should be between 60-100 bpm.

- A pulse <60 bpm is known as bradycardia and has a wide range of aetiologies (e.g. healthy athletic individuals, hypothyroidism, atrioventricular block, medications, sick sinus syndrome).

- A pulse of >100 bpm is known as tachycardia and also has a wide range of aetiologies (e.g. hyperthyroidism, anxiety, supraventricular tachycardia, hypovolaemia).

- An irregular rhythm is most commonly caused by atrial fibrillation which can be associated with hyperthyroidism.

Face

General inspection

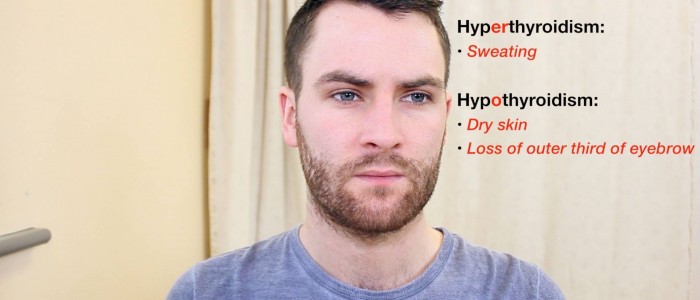

Inspect the patient’s face for clinical signs suggestive of thyroid pathology:

- Dry skin: associated with hypothyroidism.

- Excessive sweating: associated with hyperthyroidism.

- Eyebrow loss: the absence of the outer third of the eyebrows is associated with hypothyroidism (although this is a rare sign).

Eyes

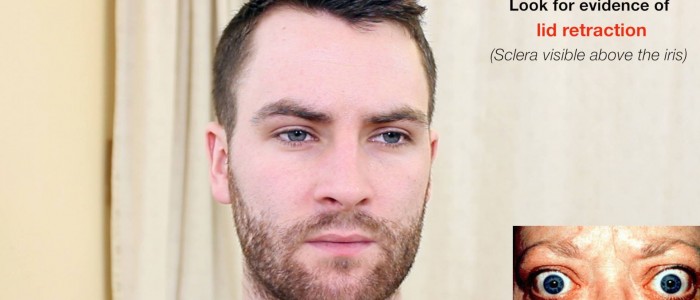

Inspect the eyes for evidence of eye pathology associated with thyrotoxicosis (e.g. Graves’ disease) including lid retraction, eye inflammation, exophthalmos (also known as proptosis), eye movement abnormalities and lid lag.

Lid retraction

To identify lid retraction inspect the eyes from the front and note if sclera is visible between the upper lid margin and the corneal limbus (this indicative of lid retraction).

Upper eyelid retraction is the most common ocular sign of Graves’ disease however it can be present in other thyrotoxic states (e.g. toxic multinodular goitre). Eyelid retraction is thought to occur due to sympathetic hyperactivity causing excessive contraction of the superior tarsal and levator palpebrae superioris muscles.

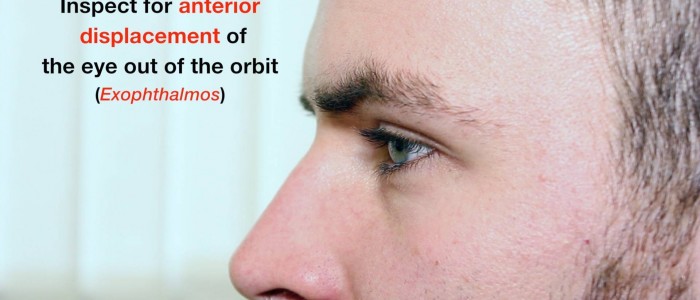

Exophthalmos

To identify exophthalmos, inspect the eye from the front, the side and from above.

Exophthalmos is bulging of the eye anteriorly out of the orbit. Bilateral exophthalmos develops in Graves’ disease, due to oedema and lymphocytic infiltration of orbital fat, connective tissue and extraocular muscles.

Eye inflammation

Inspect for evidence of inflammation affecting the eyes.

Due to lid retraction and exophthalmos, the eye is more prone to dryness and the development of conjunctival oedema (chemosis), conjunctivitis and in severe cases corneal ulceration.

Eye movements

Assess for evidence of ophthalmoplegia (e.g. restricted eye movement, diplopia) and pain during eye movement caused by Graves’ disease (lymphocytic infiltration of orbital fat, connective tissue and extraocular muscles):

1. Ask the patient to keep their head still and follow your finger with their eyes.

2. Move your finger through the various axes of eye movement (“H” shape).

3. Observe for restriction of eye movements and ask the patient to report any double vision or pain.

Lid lag

Lid lag refers to a delay in the descent of the upper eyelid in relation to the eyeball when looking downward. Lid lag is most commonly associated with Graves’ disease although it can be present in other thyrotoxic states (e.g. toxic multinodular goitre). Lid lag is thought to occur secondary to a combination of lid retraction and exophthalmos.

To assess for evidence of lid lag:

1. Hold your finger superiorly and ask the patient to follow it with their eyes, whilst keeping their head still.

2. Move your finger in a downwards direction whilst observing the patient’s upper eyelids as the patient’s eyes follow your finger. If lid lag is present, the upper eyelids will be observed lagging behind the eyes’ downward movement, with the sclera being visible between the upper lid margin and the corneal limbus.

Thyroid inspection

General inspection

Inspect the midline of the neck from the front and the sides noting any masses (e.g. goitre) or scars (e.g. previous thyroidectomy). The normal thyroid gland should not be visible.

Further inspection of a mass

If a mass is identified during the initial inspection, perform some further assessments to try and narrow the differential diagnosis.

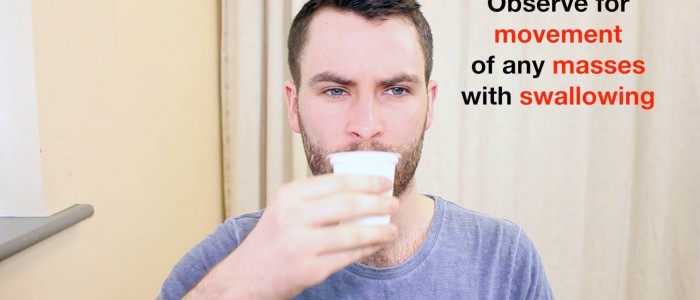

Swallowing

Ask the patient to swallow some water and observe the movement of the mass:

- Thyroid gland masses (e.g. a goitre) and thyroglossal cysts typically move upwards with swallowing.

- Lymph nodes will typically move very little with swallowing.

- An invasive thyroid malignancy may not move with swallowing if tethered to surrounding tissue.

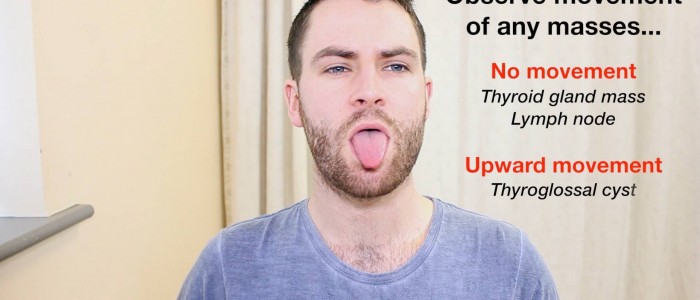

Tongue protrusion

Ask the patient to protrude their tongue:

- Thyroglossal cysts will move upwards noticeably during tongue protrusion.

- Thyroid gland masses and lymph nodes will not move during tongue protrusion.

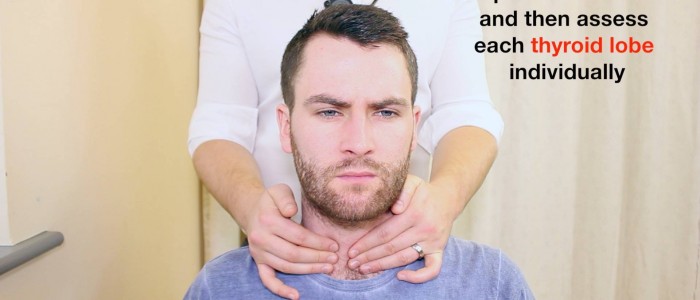

Thyroid palpation

Palpate each of the thyroid’s lobes and the isthmus:

1. Stand behind the patient and ask them to tilt their chin slightly downwards to relax the muscles of the neck to aid palpation of the thyroid gland.

2. Place the three middle fingers of each hand along the midline of the neck below the chin.

3. Locate the upper edge of the thyroid cartilage (“Adam’s apple”) with your fingers.

4. Move your fingers inferiorly until you reach the cricoid cartilage. The first two rings of the trachea are located below the cricoid cartilage and the thyroid isthmus overlies this area.

5. Palpate the thyroid isthmus using the pads of your fingers.

6. Palpate each lobe of the thyroid in turn by moving your fingers out laterally from the isthmus.

7. Ask the patient to swallow some water, whilst you feel for the symmetrical elevation of the thyroid lobes (asymmetrical elevation may suggest a unilateral thyroid mass).

8. Ask the patient to protrude their tongue (if a mass represents a thyroglossal cyst, you will feel it rise during tongue protrusion).

Characteristics of the thyroid gland

When palpating the thyroid gland, assess the following characteristics:

- Size: note if the thyroid gland feels enlarged.

- Symmetry: assess for any evidence of asymmetry between the thyroid lobes (unilateral enlargement may be caused by a thyroid nodule or malignancy).

- Consistency: assess the consistency of the thyroid gland tissue, noting any irregularities (e.g. a widespread irregular consistency would be suggestive of a multinodular goitre).

- Masses: note if there are any distinct palpable masses within the thyroid gland’s tissue (e.g. solitary thyroid nodule or thyroid malignancy).

- Palpable thrill: assess for evidence of a palpable thrill caused by increased vascularity of the thyroid gland due to hyperthyroidism (suggestive of Graves’ disease).

Characteristics of a thyroid mass

If a thyroid mass is noted assess its position, shape, consistency and mobility (i.e. is it tethered to underlying tissue).

Thyroglossal cyst

Thyroglossal cysts are the most common congenital abnormality of the neck and arise as a result of the persistence of the thyroglossal duct. The thyroglossal duct is the tract by which the thyroid gland descends during embryological development to its final position in the front of the neck. The tongue is attached to the thyroglossal duct, which is why thyroglossal cysts rise during tongue protrusion.

Types of goitre

There are several different subtypes of goitre which include:

- Diffuse goitre: the whole thyroid gland is enlarged due to hyperplasia of the thyroid tissue.

- Uninodular goitre: the presence of a single thyroid nodule which may be active (toxic) autonomously producing thyroid hormones (causing hyperthyroidism) or inactive.

- Multinodular goitre: the presence of multiple thyroid nodules which may be active or inactive. Active multinodular goitres are often referred to as a toxic multinodular goitre.

Lymph node palpation

Assess for local lymphadenopathy which may indicate the metastatic spread of primary thyroid malignancy.

1. Position the patient sitting upright and examine from behind if possible. Ask the patient to tilt their chin slightly downwards to relax the muscles of the neck and aid palpation of lymph nodes. You should also ask them to relax their hands in their lap.

2. Stand behind the patient and use both hands to start palpating the neck.

3. Use the pads of the second, third and fourth fingers to press and roll the lymph nodes over the surrounding tissue to assess the various characteristics of the lymph nodes. By using both hands (one for each side) you can note any asymmetry in size, consistency and mobility of lymph nodes.

4. Start in the submental area and progress through the various lymph node chains. Any order of examination can be used, but a systematic approach will ensure no areas are missed:

- Submental

- Submandibular

- Pre-auricular

- Post-auricular

- Superficial cervical

- Deep cervical

- Posterior cervical

- Supraclavicular

Take caution when examining the anterior cervical chain that you do not compromise cerebral blood flow (due to carotid artery compression). It may be best to examine one side at a time here.

A common mistake is a “piano-playing” or “spider’s legs” technique with the fingertips over the skin rather than correctly using the pads of the second, third and fourth fingers to press and roll the lymph nodes over the surrounding tissue.

Trachea

Inspect for evidence of tracheal deviation, which may be caused by a large goitre.

Percussion of the sternum

Percuss the sternum moving downwards from the sternal notch to assess for retrosternal dullness.

Retrosternal dullness may indicate a large thyroid mass extending posteroinferiorly to the manubrium.

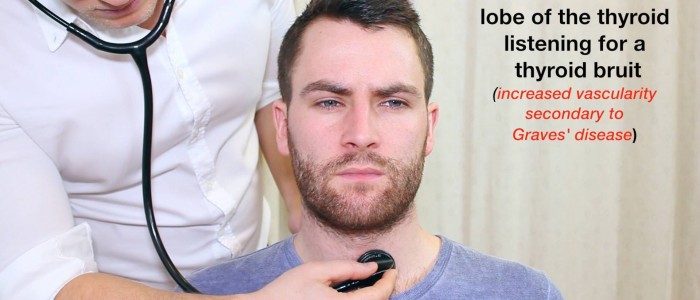

Auscultation of the thyroid gland

Auscultate each lobe of the thyroid gland for a bruit using the bell of the stethoscope.

A bruit indicates increased vascularity, which typically occurs in Graves’ disease.

Further tests

Reflexes

Reflexes are assessed to screen for hyporeflexia, which is associated with hypothyroidism. The most commonly tested reflexes are the biceps reflex or the knee jerk reflex (you only need to assess one).

Biceps reflex

1. With the patient’s arm relaxed, locate the biceps brachii tendon which is typically found at the medial aspect of the antecubital fossa.

2. Place the thumb of your non-dominant hand over the tendon and then tap your thumb with the tendon hammer.

3. Observe for a contraction of the biceps muscle and associated flexion of the elbow.

Pretibial myxoedema

Pretibial myxoedema is a form of diffuse mucinosis in which there is an accumulation of excess glycosaminoglycans in the dermis and subcutis of the skin. It usually presents itself as a waxy, discoloured induration of the skin on the anterior aspect of the lower legs (pre-tibial region). Pretibial myxoedema is a rare complication of Graves’ disease.

Proximal myopathy

Proximal myopathy is a potential complication of both multinodular goitre and Graves’ disease. Patients develop wasting of their proximal musculature causing difficulties in tasks such as standing from a sitting position.

To screen for proximal myopathy ask the patient to stand from a sitting position with their arms crossed (to minimise their ability to mask proximal muscle weakness). Make sure to stand close to the patient to prevent them from falling. An inability to stand up would suggest proximal muscle weakness.

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

Example summary

“Today I examined Mr Smith, a 32-year-old male. On general inspection, the patient appeared hyperactive at rest, with a peripheral tremor. There were no objects or medical equipment around the bed of relevance.”

“The patient was tachycardic at 105 bpm with a regular pulse. Inspection of the neck was unremarkable but palpation revealed a mass in the thyroid region that contained multiple nodules. The mass moved upwards on swallowing but was stationary during tongue protrusion. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy but retrosternal dullness was present to the level of the manubrium. Auscultation of the thyroid gland did not reveal any bruits, reflexes were normal and there was no evidence of pretibial myxoedema or proximal myopathy.”

“In summary, these findings are consistent with a toxic multinodular goitre.”

“For completeness, I would like to perform the following further assessments and investigations.”

Further assessments and investigations

- Thyroid function tests: these include TSH, T3 and T4.

- ECG: should be performed if an irregular pulse was noted to rule out atrial fibrillation.

- Further imaging: an ultrasound scan of the neck to further assess any thyroid lumps.

Reviewer

Mr Peter Truran

Consultant surgeon

References

- Herbert L. Fred, MD and Hendrik A. van Dijk. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Thyroid acropachy and pretibial myxoedema. Licence: CC BY.

- CopperKettle. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Onycholysis. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Jonathan Trobe, M.D. University of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Graves’ disease. Licence: CC BY.

- Drahreg01. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Goitre. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Bp20151130. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Thyroglossal cyst. Licence: CC BY-SA.