- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Depression is a mood (affective) disorder characterised by persistent low mood, low energy and loss of interest/enjoyment in everyday activities (anhedonia).1,2

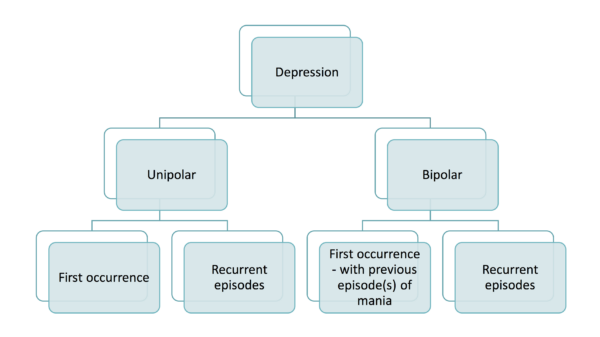

It can be unipolar (first occurrence or recurrent) or bipolar (with occurrences of mania and depression).

The onset of individual episodes is often related to stressful events or situations, and it usually runs a relapsing and remitting course.

Depression is common, with the prevalence in the United Kingdom estimated to be approximately 4.5%.

Aetiology

In depression, aetiology is multifactorial with a combination of risk factors from biological, psychological and social categories. These factors can be predisposing, precipitating or perpetuating.

Table 1. An overview of the risk factors for depression.

|

|

Biological | Psychological | Social |

| Predisposing |

|

|

|

| Precipitating (trigger) |

|

|

|

| Perpetuating (maintaining) |

|

|

|

Protective factors must also be considered including:

- Current employment

- Good social support

- Marital status: being married

Risk factors

There is often not a single identifiable cause or trigger for cases of depression. However, specific risk factors increase the chances of developing the illness.

Biological factors

Biological factors which increase the risk of depression include:

- Genetics: family history of depression in the nuclear family increases the risk to almost 30-40% and up to 50% in monozygotic twins

- Personality: dependent, anxious, impulsivity and obsessional traits

- Physical illness: neurological illnesses such as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis, hypothyroidism or chronic illnesses

- Biochemical theories/monoamine deficiency: serotonin imbalance causes depressive symptoms

- Neuroendocrine: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- Co-morbid substance misuse

- Medications: beta-blockers, steroids

- History of other mental illnesses: anxiety

Psychological factors

Psychological factors which increase the risk of depression include:

- Traumatic life events/childhood experiences: adverse experiences including loss of a loved one, lack of parental care and childhood sexual abuse

- Environmental factors (e.g. support)

- Low self-esteem and negative automated thoughts (e.g. helplessness, hopelessness, worthlessness)

- Lack of education

Social factors

Social factors which increase the risk of depression include:

- Poor social support

- Poor economic status or support

- Marital status: separated or divorced

Clinical features

A diagnosis of a depressive episode (following ICD-10/ICD-11 criteria) requires the following:

- The presence of symptoms for at least 2 weeks (this may be less if depression is severe)

- The symptoms are not attributable to other organic or substance causes (e.g. normal bereavement)

- The symptoms impair daily function and cause significant distress

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to depression history taking.

Core symptoms

The three typical core symptoms of depression include:

- Low mood

- Anhedonia: low interest or pleasure in most activities of the day

- Lack of energy (anergia)

Other core symptoms of depression include:

- Weight change: exclusion of intentional dieting

- Disturbed sleep: insomnia or hypersomnia

- Psychomotor retardation (slowed down actions) or psychomotor agitation (increased restlessness)

- Reduced libido

- Worthlessness or guilt feelings

- Decreased concentration

- Recurring thoughts of harm, death or suicide: nihilistic thoughts

Somatic/biological symptoms

Somatic symptoms of depression (also often referred to as the biological symptoms of depression) may include:

- Anhedonia

- Loss of emotional reactivity

- Diurnal mood changes: mood often worse in the morning

- Early morning wakening: typically 2-3 hours earlier than usual

- Psychomotor retardation or psychomotor agitation

- Appetite loss

- Weight loss

Psychotic symptoms

Psychotic symptoms of depression (if present, these are usually mood-congruent) may include:

- Delusions: often revolving around guilt and personal inadequacy

- Hallucinations: can be auditory, olfactory or visual

Mood-incongruent (delusions/hallucinations that are not consistent with typical depressive themes), including more first-rank symptoms (e.g. thought insertion), are often associated with other psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia.

Risk assessment

It is important to conduct a risk assessment, including:

- Risk to self: self-harm, suicide or neglect (commonest in depression)

- Risk to others: when depression presents with psychotic features, such as command hallucinations, they may be at risk of harming others

- Risk from others: patients with depressive symptoms may be more vulnerable to abuse, criminal acts or neglect

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to suicide risk assessment.

Differential diagnoses

Symptoms of depression may be present in other psychiatric illnesses and physical health illnesses, often endocrine or nutritional in aetiology.

Psychiatric differentials include:

- Depressive episode linked to substance/medication use: this by definition does not meet the ICD-10/11 diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode.

- Bipolar affective disorder: depressive episodes are interspersed with one or more manic/hypomanic episodes. Diagnosed using ICD-10/11 criteria for bipolar affective disorder.

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: symptoms occur the week before menses and resolve when menses starts. Diagnosed using ICD-10/11 criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

- Bereavement: depressive symptoms often present transiently in normal grief. Diagnosed using ICD-10/11 criteria for bereavement.

- Anxiety disorders: can frequently co-present with depressive episodes. Diagnosed using ICD-10/11 criteria for anxiety illnesses.

- Alcohol-use disorder: patients often describe sleep and concentration symptoms. Screened for with the CAGE or AUDIT questionnaires.

Physical health illness or organic illness differentials include:

- Hypothyroidism: patients often have weight and appetite changes. Diagnosis is confirmed by an elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) blood result.

- Cushing’s disease or syndrome: physical signs such as obesity and proximal muscle wasting are often present: Diagnosis is confirmed using a dexamethasone suppression test and urinary-free cortisol test.

- Vitamin B12 deficiency: features often include macrocytic anaemia on a full blood count blood test and signs of paraesthesia and impaired memory. Diagnosis is made confirmed by low serum vitamin B12 level.

Investigations

The diagnosis of a depressive episode is clinical according to the ICD-10/11 diagnostic criteria.

Screening questionnaires such as the patient-health-questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) can be used to screen for symptoms of a depressive episode.

Investigations may be considered to exclude physical/organic causes of the patient’s symptoms. These may include:

- Full blood count: anaemia

- Thyroid function test: hypothyroidism (elevated thyroid stimulating hormone)

- Vitamin B12: vitamin b12 deficiency

Imaging and other investigations (e.g. a CT head) may be performed in patients with atypical features and signs indicative of an organic pathology (e.g. low mood associated with a sudden loss of memory and change in personality).

Diagnosis

Depression is graded, following the ICD-11 criteria, as mild, moderate or severe:

- Mild depression requires two typical core symptoms plus two other core symptoms

- Moderate depression requires two typical core symptoms plus at least three other core symptoms

- Severe depression requires all three typical core symptoms plus at least four other core symptoms.

ICD-11 further classifies depressive episodes as

- Mild depressive episode, with or without somatic symptoms

- Moderate depressive episode, with or without somatic symptoms

- Severe depressive episode, with or without psychotic symptoms: these may be mood-congruent or incongruent psychotic symptoms

- Recurrent depressive disorder: when one has two more depressive episodes

Management

Management is based on the bio-psycho-social model and is divided into short-term and long-term strategies.3

Management is dependent on symptoms the individual has (e.g. difficulty sleeping).

It is important to educate patients about the disease and provide both written and verbal information to patients. The Royal College of Psychiatrists has produced a patient information leaflet for depression.

Mild depression

Short-term management

First-line management should involve initiating primarily low-intensity psychosocial interventions.

In the United Kingdom, the 2022 NICE guidelines recommend the following interventions, based on implementation, clinical and cost-effectiveness:3

- Guided self-help

- Group cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT)

- Group behavioural activation

- Individual CBT

- Group behavioural activation

- Structured group physical activity programme

- Group mindfulness and mediation

- Interpersonal psychotherapy

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants

- Counselling

- Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy

Antidepressants should not be routinely offered unless that is the patient’s preference. Exceptional cases to consider starting on biological therapy (i.e. antidepressants) include:

- Past history of moderate or severe depression

- Presence of mild depression that has been present for at least 2 years

- Presence of mild depressive symptoms after other interventions

Long-term management

Longer-term management of mild depression includes:

- Risk assessment

- Ongoing review: response to low-intensity psychosocial intervention, compliance and symptoms. An SSRI antidepressant should provide benefit within 4-6 weeks.

- Measurement scales to assess response to treatment and quality of life

- Relapse prevention plan

- Assess for social support, and review previous issues flagged up during consultations

- If taking antidepressant therapy review compliance, side effects and adjust doses if appropriate

Moderate or severe depression

Short-term management

First-line management involves a number of treatment options, which may include a combination of antidepressant therapy (biological treatment) and high-intensity psychosocial interventions.

In the United Kingdom, the 2022 NICE guidelines recommend the following interventions in descending order, based on implementation, clinical and cost-effectiveness:3

- Combination of individual CBT and an antidepressant (e.g. SSRI)

- Individual CBT

- Individual behavioural activation

- Antidepressants (e.g. SSRI) alone

- Individual problem-solving

- Counselling

- Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy

- Interpersonal psychotherapy

- Guided self-help

- Group exercise

If they are presenting with a severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms, then treatment should be augmented with an antipsychotic (quetiapine or olanzapine).

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) should be considered in severe cases of depression where:

- The patient has a strong preference for ECT: this usually applies when patients have responded to ECT well before

- Rapid treatment of the patient is needed: cases of life-threatening depression where the patient is not eating or drinking

- Multiple other treatments have been trialled unsuccessfully

Long-term management

Long-term management of moderate or severe depression includes:

- Risk assessment

- Review their response to high-intensity psychosocial intervention compliance and symptoms

- Review their response to antidepressant therapy, compliance, side effects and adjust doses if appropriate

- Measurement scales to assess response to treatment and quality of life

- Relapse prevention plan

- Assess social support and previous issues flagged up during the consultation

Complications

Complications of depression include:3

- Suicide: the risk of suicide in patients with depression is four times higher than in patients without depression

- Substance misuse and alcohol use problems: patients are at increased risk of becoming dependent on substances

- Persistent symptoms: 10-20% of patients will have persistent symptoms over 2 years

- Recurrence of depressive episodes: most patients have a recurrence in later life

- Reduced quality of life: patients may struggle with employment and relationships

- Antidepressant side effects: may include sexual dysfunction, risk of self-harm, weight gain, hyponatraemia and agitation

Key points

- Depression is a mood (affective) disorder characterised by persistent low mood, low energy and loss of interest/enjoyment in everyday activities (anhedonia).

- A diagnosis of a depressive episode is clinical, requiring the identification of core symptoms to determine the severity of the episode.

- Investigations should be considered to exclude organic illnesses associated with depressive symptoms, including hypothyroidism.

- Management follows the bio-psycho-social model, with a number of psychological therapies and social interventions as treatment options.

- Long-term management should focus on risk assessment and treatment response.

- Complications of depression include suicide (risk is 4x higher), substance/alcohol misuse, persistent/recurrent symptoms, reduced quality of life and antidepressant side effects.

Reviewers

Dr Nusrat Khan

Clinical Associate Professor and Consultant Psychiatrist

Newcastle University

Dr Kimberly Kendall

ST5 General Adult Psychiatry

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Greg Lydall, M.D., Noreen Jakeman, Sheena Webb (2009) ‘Affective Disorders’, in Sarah Stringer, L.C., Susan Davison, Maurice Lipsedge (ed.) Psychiatry P.R.N. Oxford University Press

- International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11) (2021), World Health Organization (WHO) 2019/2021. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2022). Depression in adults: treatment and management (update). Available from: [LINK]