- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Of all cancers affecting the liver, 10% are primary cancers arising from the liver itself, and 90% are secondary metastases from other sites in the body. This article will focus on primary cancers of the liver, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Other types of primary liver cancer include intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICCA), which I’ll cover in a separate article, and other extremely rare tumours such as angiosarcoma of the liver. I’ll also do another post on liver metastases soon.

Due to the increasing prevalence of liver cirrhosis, the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma is rising dramatically, and the human race has responded by developing an effective vaccine against one of the major causes (hepatitis B virus) and a variety of new and innovative treatments to tackle the tumours.

Introduction.

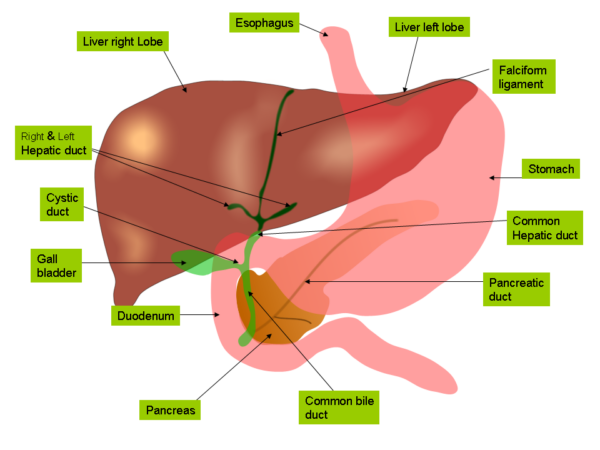

Anatomy of the liver

.

- the liver is the largest abdominal organ, and is a soft wedge-shaped mass situated in the upper supracolic part of the abdominal cavity just below the diaphragm

- it has a smooth convex upper surface moulded to the undersurface of the diaphragm, an irregular visceral surface indented by adjacent abdominal organs, and a sharply defined inferior angle between the two surfaces, which moves during respiration and is palpable on examination

- most of the bulk of the liver lies beneath the ribcage on either side, and is therefore fairly inaccessible on abdominal examination – normally <2cm of the liver edge is palpable

- the liver has four lobes: a large right lobe, a smaller left lobe, and posteromedial caudate and quadrate lobes, which are functionally part of the right lobe

- surgeons also divide the liver into eight functionally independent segments using the Couinaud classification, which is based on their blood supply and biliary drainage

- there are several important structures associated with the posterior visceral surface of the liver: the inferior vena cava, the gall bladder, the porta hepatis, and the ligamentum teres and ligamentum venosum (remnants of fetal circulation). These structures form a characteristic “H” shape which delineates the caudate and quadrate lobes.

- the liver is surrounded by a tough fibrous capsule known as Glisson’s capsule

- it also has a number of peritoneal folds or “ligaments” attaching it to the diaphragm and the abdominal walls. These include the falciform ligament dividing the right and left lobes anteriorly, right and left coronary ligaments superiorly and right and left triangular ligaments posteriorly.

- the two layers of the right coronary ligament separate and become widely spaced as they pass down the posterior surface of the right lobe, forming a “bare area” on the back of the liver devoid of peritoneal coverings. This lies in direct contact with the diaphragm and the right adrenal gland.

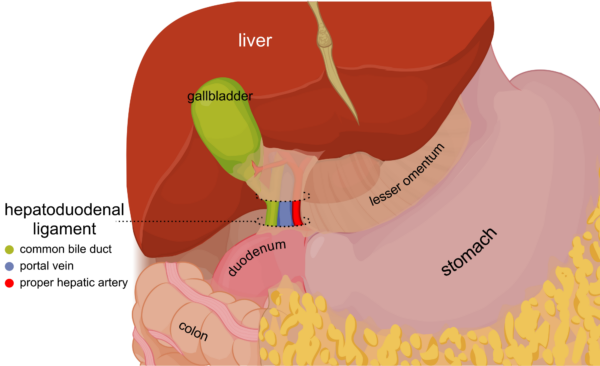

- the lesser omentum is another double-layered sheet of peritoneum which extends downwards, connecting the liver to the stomach and the first part of the duodenum. Its lower free edge is called the hepatoduodenal ligament and contains the portal triad, hepatic nerve plexus and lymphatics.

.

- the liver is a highly vascularised organ which receives 25% of the cardiac output (1.5L/min)

- it has a unique blood supply, in that it receives blood from both an artery and a vein:

- 25% of its blood supply is derived from the hepatic artery, a branch of the coeliac trunk, which supplies oxygenated blood to the liver.

- the other 75% comes from the portal vein, which is formed by the union of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins behind the neck of the pancreas. This drains nutrient-rich blood from the stomach, small intestines and most of the large intestine into the liver.

- venous blood from the liver drains directly into the inferior vena cava via three hepatic veins

- the portal triad consists of the hepatic artery, portal vein and common bile duct. These structures travel together towards the liver within the hepatoduodenal ligament (the lower free edge of the lesser omentum), and their branches enter its visceral posterior surface via the porta hepatis or “hilum” of the liver. The portal vein is the most posterior structure, and the bile duct is the most anterior, making it easy to access surgically. The artery lies between the two.

Physiology

- the liver performs an absolutely enormous range of vital functions

- they can be categorised into filtration, metabolic, storage, synthetic and detoxification functions

- filtration: it receives and filters massive amounts of venous blood from the intestines, and any contaminants are removed by special phagocytes called Kupffer cells which line hepatic sinusoids.

- metabolic: it processes and metabolises substances absorbed by the digestive system, and has vital roles in the metabolism of carbohydrates, fats and amino acids. It also conjugates bilirubin, a red blood cell breakdown product.

- storage: it stores substances such as glycogen, iron, copper, and vitamins A, B12, D and K.

- synthetic: it produces bile and secretes it into the gallbladder and duodenum. Bile neutralises stomach acid, emulsifies dietary fats to facilitate the absorption of cholesterol, triglycerides and fat-soluble vitamins, and allows excretion of excess bilirubin and cholesterol. The liver also produces other essential substances such as clotting factors, albumin, thrombopoietin and IGF-1.

- detoxification: it breaks down hormones such as insulin and sex hormones, and converts toxic ammonia into urea, which is excreted by the kidneys. It also has a vital role in drug metabolism.

- as the liver is such a multi-talented organ, liver failure is a complex disease process. However, its symptoms, signs and complications can each be explained by the loss of one of these functions.

Epidemiology

- primary liver cancers account for 1.3% of cancers in the UK (about 4000 cases per year)

- overall, it is the eighteenth most common cancer and causes 2.6% of cancer deaths (about 4000 per year)

- in men, it is the fourteenth most common cancer and has a lifetime risk of 0.86%, or 1 in 117

- in women, it is the nineteenth most common cancer and has a lifetime risk of 0.47%, or 1 in 214

- it has a peak incidence in people in their late 60s and 70s and is rare under the age of 40

- incidence has increased by over a third over the past 10 years, probably due to the increasing prevalence of common risk factors such as alcohol excess, obesity and chronic viral hepatitis

- the incidence is much higher in developing countries – liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer worldwide (around 750,000 cases per year) with a peak incidence in Asian countries and sub-Saharan Africa due to viral hepatitis and/or the consumption of food contaminated with aflatoxins

Aetiology and risk factors

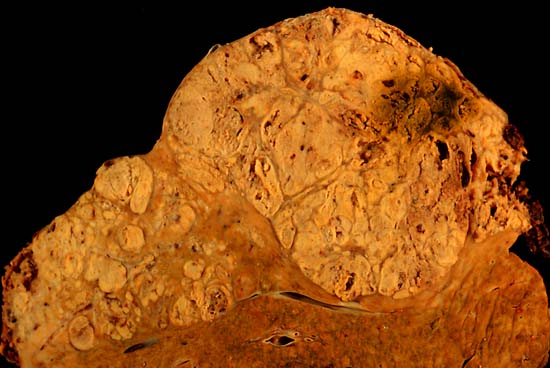

- 90% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma have a history of liver cirrhosis. Cirrhosis causes toxic damage to hepatocytes, the release of inflammatory cytokines, prolonged oxidative stress, and increased cell turnover, which ultimately results in DNA damage, mutations and the development of cancer. Tumours can either form a distinct mass or undergo widespread diffuse growth throughout the liver. The incidence of HCC in patients with cirrhosis is 5% per year, which makes the 20-year cancer risk virtually 100%. As many as 30-50% of cases are detected too late for curative treatment, but screening programmes are now in place to try and catch more cancers early.

- there are many causes of liver cirrhosis, which are associated with variable increases in HCC risk:

- alcoholic liver disease (ALD) – 5x risk

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) – 4x risk

- viral hepatitis: hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection – can increase risk up to 60x, responsible for 85% of cases worldwide

- autoimmune liver diseases such as primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC – 6x risk), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC – mainly increases the risk of cholangiocarcinoma), and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH – much lower risk than PBC)

- haemochromatosis – some sources say it leads to >100x risk

- Wilson’s disease

- alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- cystic fibrosis (CF) liver disease

- porphyria cutanea tarda, hereditary tyrosinaemia and other rare metabolic disorders

- drug-induced hepatotoxicity (e.g. paracetamol overdose, chemotherapy, antibiotics)

- amongst patients with cirrhosis, additive factors which further increase risk of HCC include male gender (3-6x risk), age >40, and non-Caucasian ethnic origin

- another major risk factor is exposure to aflatoxins – these are fungal agents released by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus which can contaminate grains, nuts and other foods in developing countries. Once eaten, they are metabolised to epoxide toxins within the liver which can interfere with tumour suppressor genes like p53 and are extremely carcinogenic.

- parasitic infections such as schistosomiasis can increase HCC risk. Infection with liver flukes like Clonorchis Sinensis and Opisthorcis viverrini increases the risk of cholangiocarcinoma but not HCC.

- even in the absence of cirrhosis, lifestyle factors such as alcohol excess (5x risk), smoking (1.6x risk) and obesity (1.5x risk) are very important

- medical conditions such as diabetes (1.8x risk), immunosuppression due to HIV infection (5x risk) or organ transplant (2x risk), cholecystectomy and previous blood transfusions add to the risk

- a family history of HCC (1.5x risk), hereditary forms of cirrhosis like haemochromatosis or Wilson’s, or other metabolic disorders such as porphyria or tyrosinaemia is important to ask about

- exposure to chemicals such as vinyl chloride increases the risk of angiosarcoma of the liver

- use of anabolic or contraceptive steroids can promote the growth of pre-existing liver adenomas and may also independently increase HCC risk

- protective factors include female gender, hepatitis B vaccination, drinking coffee, and eating fruit

Histopathological types of liver cancer

- ~90% hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

- fibrolamellar HCC is a rare subtype of hepatocellular carcinoma which tends to occur in young people without a history of cirrhosis or other major risk factors. It has a much better prognosis.

- ~10% intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICCA) – this will be covered in a separate article soon

- <1% sarcomas: angiosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, undifferentiated embryonal

- <1% epithelioid haemangioendothelioma (EHE) – diffuse, multifocal and rarely resectable

- <1% primary hepatic lymphoma

- <1% hepatoblastoma – affects the under 5s and is the commonest liver cancer in children, but is still extremely rare. Fewer than 15 cases are diagnosed each year.

Symptoms

- the patient may be completely asymptomatic and cancer may be an incidental finding on imaging during the investigation of abdominal pain or deranged LFTs

- the patient may be asymptomatic and cancer may be found during routine screening for cirrhosis

- patients with underlying liver disease often present with features of decompensated cirrhosis such as ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), jaundice, variceal bleeding, encephalopathy or hepatorenal syndrome

- as the tumour grows, patients may develop upper abdominal pain, indigestion or early satiety

- less commonly, liver tumours can spontaneously rupture, causing intraperitoneal haemorrhage and presentation with an acute abdomen or shock

- if the tumour invades vascular structures, it can cause portal hypertension with variceal bleeding and ascites, or IVC thrombosis with risk of pulmonary embolism and sudden death

- there may be symptoms of paraneoplastic syndromes such as polycythaemia, hypoglycaemia or hypercalcaemia

- symptoms of advanced disease include fatigue, malaise, weight loss, anorexia, pruritis, fever

- symptoms of metastatic disease may include shortness of breath and haemoptysis (lungs), bone pain and pathological fractures (bones) and neurological deficits or seizures (brain)

Signs

- general examination may reveal pallor and weight loss/cachexia, or signs of chronic liver disease such as clubbing, palmar erythema, leuconychia, bruising, spider naevi, gynaecomastia, caput-medusae and peripheral oedema

- there may be signs of decompensation such as ascites, peritonitis, sepsis, jaundice, haematemesis/malaena and hepatic encephalopathy with confusion and “liver flap”

- abdominal examination may reveal hepatomegaly, which can be smooth or hard and irregular, abdominal distension and splenomegaly due to portal hypertension

- a systolic liver bruit may be audible over the tumour

Differential diagnosis – liver failure/liver mass

Other causes of liver failure include:

- acute liver failure due to hepatitis, drug overdose or other causes

- chronic liver failure due to cirrhosis, which may be compensated or decompensated

A mass in the liver could be due to:

- generalised hepatomegaly – acute hepatitis, early cirrhosis, heart failure, tricuspid regurgitation (pulsatile), sickle cell disease, inborn errors of metabolism

- liver cysts – simple cyst, inherited polycystic kidney/liver disease, hydatid cyst (tapeworm)

- liver abscesses – could be pyogenic (cirrhosis is a proven risk factor) or amoebic; the patient will generally be unwell with pyrexia, pain, GI upset and weight loss

- benign liver tumours – haemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia, adenoma

- primary liver malignancy – HCC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, other rare types

- secondary liver metastases – common primary sites include GI, lung and breast cancers

- other causes of right upper quadrant mass – cholecystitis, gallbladder mucocoele, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, mass within the small bowel, ascending/transverse colon or connective tissues

Investigations

Diagnostic tests for patients with suspected liver cancer include:

- history and clinical examination including abdominal palpation

- patients classically present with features of underlying chronic liver disease, and therefore need a full set of baseline blood tests including FBC (for haemoglobin and white cell count), U+E (for renal function and upper GI bleed), LFTs (for liver function), coagulation studies (for bleeding disorders due to failure of liver synthetic function), bone profile (to check calcium and phosphate), magnesium (low in alcoholics), glucose (for hypoglycaemia) and G&S or crossmatch if indicated

- patients presenting with new-onset of jaundice or liver failure should also have a “liver screen” to test for common causes – this includes, alongside the above tests, gamma-GT +/- ethanol level, lipid profile, serology for hepatitis A, B, C and E, CMV and EBV, HIV test, immunoglobulin electrophoresis and autoantibody screen, ferritin and iron studies, caeruloplasmin, and alpha-1 antitrypsin levels

- tumour markers are very useful in diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma: alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is a fetal glycoprotein antigen which is raised in 80% of HCCs, but may be normal in smaller tumours <3cm in size and is more likely to be falsely negative in white patients. The normal range is 10-20ng/ml; a level of >200 is highly suggestive of HCC, and >400 is considered diagnostic. A dramatically raised AFP is considered a poor prognostic indicator. It is important to remember that AFP is sensitive but not specific to HCC – it can also be raised in teratomas, yolk sac tumours, other gastrointestinal malignancies, acute hepatitis, cirrhosis and pregnancy.

- transabdominal ultrasound allows examination of the liver and other abdominal organs, assessment of any masses and ultrasound-guided liver biopsy if appropriate

- abdominal CT scan can also be used to provide more detailed imaging of the liver, with information about tumour vascularity, portal vein invasion and lymph involvement to allow surgical planning +/- CT-guided liver biopsy if appropriate, Up to 75% of tumours are multifocal at the time of diagnosis.

- MRI provides highly detailed imaging of soft tissue structures and is particularly good for differentiating benign lesions from malignant ones

- if cholangiocarcinoma is suspected, the patient may require MRCP/ERCP and biopsy

Care needs to be taken when deciding whether to biopsy liver tumours, as the cancer cells can seed along the biopsy tract and cause local recurrence. Liver biopsy is also associated with other serious complications such as bleeding. Patients with a malignant-looking liver mass that is potentially resectable should ideally be referred directly for surgical opinion without a biopsy being performed. Due to concerns surrounding biopsy complications, there are now three accepted sets of diagnostic criteria which can be used, two of which do not require a biopsy to be taken:

- cytohistological diagnosis from a biopsy of the lesion

- radiological diagnosis using 2 imaging techniques (USS/CT/MRI) showing a focal lesion >2cm in diameter with arterial hypervascularisation

- combined diagnosis using AFP level >200ng/ml and imaging criteria as described above.

Staging investigations for patients with confirmed liver cancer include:

- CT chest, abdomen and pelvis +/- head to assess for metastases

- a bone scan may be indicated to check for bone metastases

- staging laparoscopy can be used to look for peritoneal disease

- the severity of liver disease and portal hypertension can be staged using blood tests and wedge hepatic venous pressure measurements respectively

Grading – how aggressive is it?

There are several available systems for the histopathological grading of HCC, but most centres nowadays use a simple approach based on the degree of differentiation within the cancer cells:

- Grade I – well-differentiated (good)

- Grade II – moderately differentiated (OK)

- Grade III – poorly differentiated (bad)

- Grade IV – undifferentiated (very bad)

Studies have shown that the grade of a hepatocellular carcinoma is only a weak prognostic indicator, meaning it is not particularly useful in dictating treatment or predicting the likelihood of survival..

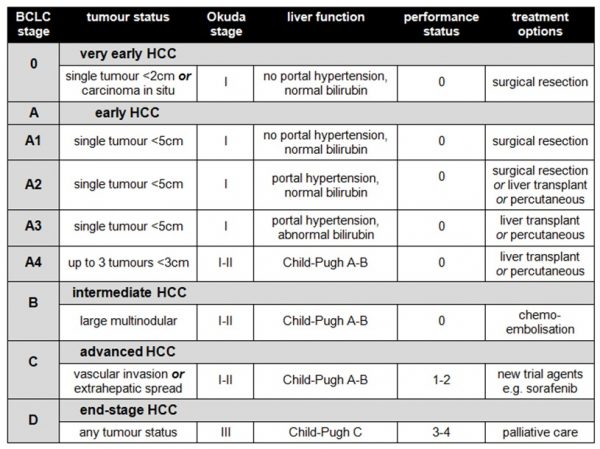

Staging – how far has it spread?

When staging HCC, it is important to take into account not only the stage of the cancer but also the severity of any underlying cirrhosis and the patient’s overall health status, as all of these will have significant bearing in helping the surgeon decide on the most appropriate course of treatment. As a result, the staging process is rather complicated and involves a lot of tables (sorry).

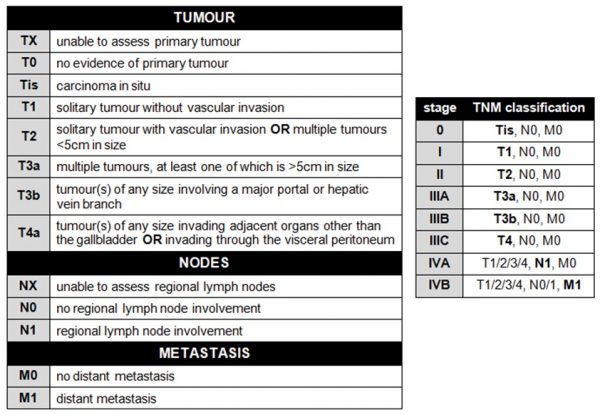

The tumour itself is staged using the TNM (tumour nodes metastasis) system. The TNM criteria and their associated numerical staging stratification are shown in the tables below:.

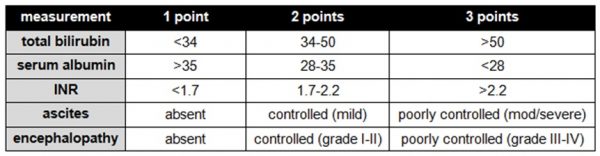

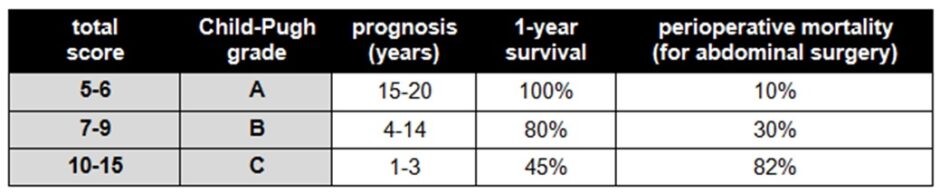

The severity of liver cirrhosis is graded using the Child-Pugh system, which combines several measures of the liver’s synthetic and detoxification functions:

.

.

.

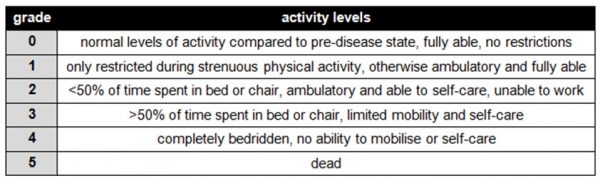

The patient’s overall health is measured using the WHO performance status criteria:

.

.

If that’s not enough scoring systems for you already, the above results need to then be combined to produce a composite indicator of the stage of the patient’s disease. There are three main systems, the BCLC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer) system, the CLIP (Cancer of the Liver Italian Program) system and the JIS (Japanese Integrated Scoring) system. The BCLC system is commonly used in the UK, as it correlates best with patient outcomes and facilitates evidence-based decisions about treatment:

.

.

If you want to find out more about the other available scoring systems, including the OKUDA tumour score used in the BCLC system, you’ll find a decent review article to download here.

Management

Management strategies depend on multiple factors, and there are a wide variety of options available.

If the patient has been newly diagnosed with cirrhosis as well as their HCC, it is important to attempt to treat the underlying cause. This might include cessation of alcohol intake for ALD, lifestyle modifications for NAFLD, or peginterferon and ribavirin for hepatitis C. For more information on the medical management of liver disease, see here for our Geeky Medics Hepatology guides. Patients should also be screened for complications of cirrhosis, such as ascites or oesophageal varices.

Conservative management may be considered best in some cases, for example in elderly frail patients or those with decompensated end-stage cirrhosis who are unfit for active treatment. This involves “watchful waiting” with monitoring of AFP levels and the patient’s clinical condition.

Medical therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma are fairly limited. External beam radiotherapy is rarely used, as liver cells are extremely sensitive to its toxic effects, meaning the whole liver could die. Systemic chemotherapy is usually futile as HCCs are chemoresistant tumours. Potential future options include:

- sorafenib, a targeted oral molecular therapy which blocks cancer cell division and angiogenesis, is licensed for use in inoperable HCC and has been shown to improve survival. However, it has not been approved by NICE for use in the UK. Some patients may receive it on an individual basis from a specialist, or as part of a clinical trial.

- retinoids

- adaptive immunotherapy using primed peripheral lymphocytes

- advanced targeted radiotherapy techniques such as stereotactic radiosurgery

- newer chemotherapy regimes such as gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GEMOX), which has been shown to downsize tumours and improve survival in advanced disease, but has high rates of toxicity

Minimally invasive localised therapies are generally used to treat inoperable tumours. They can also be used to downstage borderline unresectable tumours to make surgical treatment possible.

- percutaneous ablation with ethanol injection, radiofrequency or microwave ablation, cryotherapy, acetic acid or laser. This is an effective treatment: outcomes have been found to be as good as surgical resection for small HCCs. However, there are some disadvantages, as it is hard to reach posterior liver lesions percutaneously, there is a risk of bile duct injury, and the patient needs to have good underlying liver function as the treatment kills off bits of it.

- transhepatic arterial chemoembolisation (TACE) uses gelatin or cellulose fragments to block off the blood supply to the tumour, then delivers high-concentration localised chemotherapy to the area. The blockage of the blood supply is very important as it disrupts the oxygen and nutrient supply to the tumour and allows much higher chemotherapy doses than can safely be used systemically. Patients tend to receive treatments at 3- to 6-monthly intervals. TACE is good for large, multifocal tumours with good underlying liver function and no metastases, and after successful treatment median survival is longer than 2 years. However, it is contraindicated in portal vein thrombosis and again requires good underlying liver function, so may not be suitable for patients with cirrhosis.

- selective internal radiotherapy treatment (SIRT) is a newer therapy which uses radioactive yttrium beads to block off the blood supply to the tumour and deliver a dose of targeted radiotherapy to the area within a 4mm radius around them. It is basically TACE but with radiotherapy instead of chemotherapy. The radioactivity wears off within a few days, making it a safe treatment, but patients may need to be kept in isolation for 24-48 hours after the procedure depending on local radiation safety protocols. So far, NICE has only approved SIRT for use in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases, but has stated that it can be used to treat inoperable HCC within specialist clinical trials.

- irreversible electroporation (IRE) is an innovative non-thermal cell destruction technique which uses the direct application of short bursts of high-voltage electric current to destroy cancer cells. Because it does not generate high temperatures, it minimises damage to surrounding tissues such as blood vessels and bile ducts. It has been shown to be a very effective treatment, but can cause lethal arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia if the electric current is not properly synchronised with the patient’s cardiac cycle. Again, it is currently only approved by NICE for use in clinical trials.

Surgical management is an option for some patients, and may involve resection or transplant:

- liver resection can be used to remove solitary tumours <3cm in diameter. Potential procedures include segmental/wedge resections, right or left hepatectomy, or caudate resection. Liver surgery significantly increases 3-year survival from 13% to 59%, but it is a major undertaking which requires very good preoperative liver function and general performance status. Operative mortality is about 3% overall, but is much higher in patients with cirrhosis. Liver failure is the commonest cause of death after liver resection, but if patients survive, their remaining liver tissue undergoes rapid hyperplasia and hypertrophy – amazingly, it can increase to two-thirds of its original size within weeks. About 50% of patients have a recurrence within 3 years, and up to 80% will within 5 years. .

This awesome video from Saket Singhi on YouTube shows the key steps in an open resection of the left lateral segment of the liver. You can see how the liver is mobilised by division of its peritoneal attachments, then the portal triad is temporarily occluded using tape and a tube to control bleeding. The left lateral segment is then carefully demarcated and removed using high power diathermy, and any vessels encountered along the way are ligated with ties, clips or sutures. The number of times they have to do this makes you realise what an enormous blood supply the liver has! Towards the end, you can also see the heart beating against the diaphragm just above the surgeons’ hands, which is rather cool..

- liver transplantation is another option for patients who meet the Milan criteria, which are:

- 1 lesion <5cm in size or up to 3 lesions <3cm in size

- no metastatic disease

- no macroscopic vessel invasion on CT/MRI

- only 5% of patients meet the transplant criteria at the time of diagnosis, and unfortunately, many of these are not fit for major surgery due to their underlying comorbidities. Others undergo disease progression and deteriorate whilst waiting on the transplant list. However, for patients who do proceed to transplant, the risk of recurrence is <10% and 5-year survival is >70%. Operative mortality is <10%. Transplant is the best available curative treatment for HCC, as it treats the underlying cirrhosis as well as the tumour. Newer techniques such as living donor and split liver transplantation are increasingly being used and have shown very promising results.

If you’ve ever wanted to see a liver transplant without spending 7 hours in theatre desperately trying to get a decent view over a surgeon’s shoulder, check out this video from Ivan Michalek in Slovakia, which has great close-up views highlighting the main steps of the operation from start to finish. It’s pretty badass surgery and not for the fainthearted! You’ll notice quite a lot of blood knocking around in the abdomen during the procedure; ideally, the operation should be as bloodless as possible, as bigger intraoperative blood transfusions are associated with higher rates of complications, including recurrence of liver cancer. To minimise bleeding, some centres put patients on venous bypass (using cannulae in the femoral and internal jugular veins) to allow the IVC to be clamped off completely during the transplant.

Follow-up and prognosis

- the overall prognosis for liver cancer is very poor (5.5% 5-year survival) – this is due to both the aggressive nature of the cancer itself, and the poor outlook associated with advanced liver cirrhosis

- there is a median prognosis of about 6 months from the time of diagnosis

- however, the small proportion of patients with early-stage disease who undergo treatment have a much better prognosis, with around 50-70% 5-year survival

- patients who undergo surgery for liver cancer are usually followed up by a specialist HPB (hepatopancreatobiliary) surgical unit with AFP levels and imaging every 6-12 months to monitor for recurrence, and will also receive ongoing input from the gastroenterology team for management of cirrhosis if required

- patients with advanced incurable disease may be referred for management by palliative care specialists, either as inpatients or in the community

Prevention strategies

There are multiple public health interventions in place which aim to reduce the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, both in the general public and specific high-risk populations. These include:

- education and awareness schemes to encourage a healthy alcohol intake, smoking cessation and the reduction of lifestyle factors such as obesity and poor diet which can lead to NAFLD

- hepatitis B vaccination for healthcare workers and other at-risk individuals

- needle exchange facilities and methadone programmes for IV drug users

- use of sterilised blood products for transfusion

- screening and decontamination of grains, nuts and other foods to neutralise aflatoxins

There is no routine population screening for HCC, but there is a targeted screening programme for high-risk cirrhosis patients which aims to detect tumours at an earlier, treatable stage.

- candidates for screening include men with ALD and PBC, and all patients with hepatitis B, hepatitis C, haemochromatosis and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- patients are screened using AFP levels and ultrasound every 6-12 months, and any >2cm lesions found are further investigated using CT scan +/- FNA biopsy. Smaller lesions are monitored with 3-monthly ultrasound and may be investigated with CT/MRI if they look suspicious.

- an AFP of >400ng/ml is considered diagnostic, but most smaller tumours have levels below the 200ng/ml threshold of significance, and 20% of HCCs do not produce it at all. False positives may occur as AFP is also produced by cirrhosis nodules and a range of other disease pathologies.

- ultrasound is both sensitive and specific for larger tumours, but can miss up to a third of smaller tumours depending on the level of experience of the sonographer

- the two screening tests are much more reliable when used together. According to the combined diagnostic criteria, an AFP of >200 with a >2cm liver lesion on ultrasound is diagnostic of HCC.

- overall, the value of screening is still being questioned, due to the lack of curative treatment options available for patients with established cirrhosis. It is arguable that there is little benefit in catching the cancer at an earlier stage if the patient’s comorbidities will prevent you from doing anything to definitively treat it. However, studies have shown that early diagnosis does prolong survival.

Specialist review

Mr Avinash Sewpaul

ST8 in HPB & Transplant Surgery

References

Images:

- By Jiju Kurian Punnoose [CC BY-SA 4.0], from Wikimedia Commons

- By Olek Remesz (wiki-pl: Orem, commons: Orem) [CC BY-SA 3.0], from Wikimedia Commons

Further reading sources:

- Cancer Research UK – Cancer incidence for common cancers – Available from: [LINK]

- Cancer Research UK – Liver Cancer – Available from: [LINK]

- Medscape eMedicine – Hepatocellular Carcinoma – Available from: [LINK]

- Paradis V; “Histopathology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma“; Multidisciplinary Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Recent Results in Cancer Research 190 2013

- Patient UK – Hepatocellular Carcinoma – Available from: [LINK]

- Subramaniam S, Kelley RK, Venook AP; “A review of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) staging systems“; Chinese Clinical Oncology 2013 2(4):33