- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This guide outlines an approach to performing a focused aortic stenosis examination and is intended as a supplement to the Geeky Medics cardiovascular examination guide.

In OSCE scenarios, you may be asked to perform a focused examination to determine the presence (or absence) of a certain condition. In order to do this, you need to be comfortable with the relevant basic system examination (i.e. for an aortic stenosis examination you need to be comfortable with performing a cardiovascular examination).

Background

Aortic stenosis (AS) refers to a tightening of the aortic valve at the origin of the aorta.

Aetiology

AS has a number of potential causes including:

- Calcification of the aortic valves: this is the most common cause of AS in developed countries, typically occurring in elderly adults.

- Congenital abnormality of the aortic valve: the aortic valve is normally composed of three cusps (known as a tricuspid valve), but in some cases, individuals have only two cusps (known as a bicuspid valve) which predisposes them to the development of AS as well as aortic regurgitation.

- Rheumatic heart disease: a rare cause of AS in developed countries.

When examining a patient with suspected AS you should look for clinical features of aortic stenosis and its potential underlying causes.

Clinical features of aortic stenosis

Aortic stenosis typically presents with the following triad of symptoms (use the mnemonic SAD to remember them):

- Syncope (exertional)

- Angina

- Dyspnoea

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language.

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Adjust the head of the bed to a 45° angle and ask the patient to lay on the bed.

Adequately expose the patient’s chest for the examination (offer a blanket to allow exposure only when required and if appropriate, inform patients they do not need to remove their bra). Exposure of the patient’s lower legs is also helpful to assess for peripheral oedema and signs of peripheral vascular disease.

Ask the patient if they have any pain before proceeding with the clinical examination.

General inspection

Clinical signs

Inspect the patient from the end of the bed whilst at rest, looking for clinical signs suggestive of underlying pathology:

- Cyanosis: a bluish discolouration of the skin due to poor circulation (e.g. peripheral vasoconstriction secondary to hypovolaemia) or inadequate oxygenation of the blood (e.g. right-to-left cardiac shunting).

- Shortness of breath: may indicate underlying cardiovascular disease (e.g. aortic stenosis with secondary left ventricular hypertrophy).

- Pallor: a pale colour of the skin that can suggest underlying anaemia (e.g. haemorrhage, chronic disease) or poor perfusion (e.g. congestive cardiac failure).

- Malar flush: plum-red discolouration of the cheeks associated with mitral stenosis (can develop as a result of rheumatic heart disease).

- Oedema: typically presents with swelling of the limbs (e.g. pedal oedema) or abdomen (i.e. ascites). There are many causes of oedema, but in the context of a cardiovascular examination OSCE station, congestive heart failure is the most likely culprit.

- Bruising: may indicate recent falls secondary to syncope.

Objects and equipment

Look for objects or equipment on or around the patient that may provide useful insights into their medical history and current clinical status:

- Medical equipment: note any oxygen delivery devices, ECG leads, medications (e.g. glyceryl trinitrate spray), catheters (note volume/colour of urine) and intravenous access.

- Mobility aids: items such as wheelchairs and walking aids give an indication of the patient’s current mobility status.

- Pillows: patients with congestive heart failure typically suffer from orthopnoea, preventing them from being able to lie flat. As a result, they often use multiple pillows to prop themselves up.

- Vital signs: charts on which vital signs are recorded will give an indication of the patient’s current clinical status and how their physiological parameters have changed over time.

- Fluid balance: fluid balance charts will give an indication of the patient’s current fluid status which may be relevant if a patient appears fluid overloaded or dehydrated.

- Prescriptions: prescribing charts or personal prescriptions can provide useful information about the patient’s recent medications.

Hands

The hands can provide lots of clinically relevant information and therefore a focused, structured assessment is essential.

Inspection

General observations

Inspect the hands and note your findings:

- Colour: pallor suggests poor peripheral perfusion (e.g. congestive heart failure) and cyanosis may indicate underlying hypoxaemia.

- Tar staining: caused by smoking, a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease (e.g. aortic stenosis, coronary artery disease, hypertension).

- Xanthomata: raised yellow cholesterol-rich deposits that are often noted on the palm, tendons of the wrist and elbow. Xanthomata are associated with hyperlipidaemia (typically familial hypercholesterolaemia), another important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (e.g. aortic stenosis, coronary artery disease, hypertension).

Palpation

Temperature

Place the dorsal aspect of your hand onto the patient’s to assess temperature:

- In healthy individuals, the hands should be symmetrically warm, suggesting adequate perfusion.

- Cool hands may suggest poor peripheral perfusion (e.g. congestive cardiac failure, acute coronary syndrome).

- Cool and sweaty/clammy hands are typically associated with acute coronary syndrome.

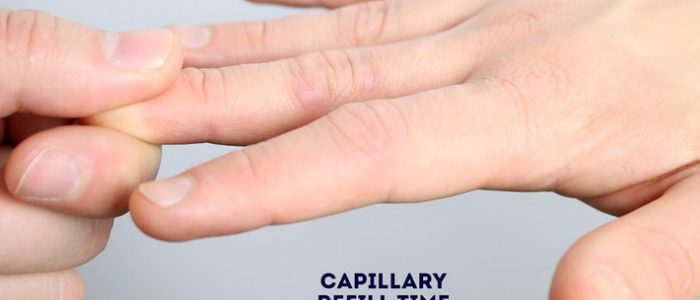

Capillary refill time (CRT)

Measuring capillary refill time (CRT) in the hands is a useful way of assessing peripheral perfusion:

- Apply five seconds of pressure to the distal phalanx of one of a patient’s fingers and then release.

- In healthy individuals, the initial pallor of the area you compressed should return to its normal colour in less than two seconds.

- A CRT that is greater than two seconds suggests poor peripheral perfusion (e.g. hypovolaemia, congestive heart failure) and the need to assess central capillary refill time.

Pulses and blood pressure

Radial pulse

Palpate the patient’s radial pulse, located at the radial side of the wrist, with the tips of your index and middle fingers aligned longitudinally over the course of the artery.

Once you have located the radial pulse, assess the rate and rhythm.

Brachial pulse

Palpate the brachial pulse

Palpate the brachial pulse in their right arm, assessing volume and character:

1. Support the patient’s right forearm with your left hand.

2. Position the patient so that their upper arm is abducted, their elbow is partially flexed and their forearm is externally rotated.

3. With your right hand, palpate medial to the biceps brachii tendon and lateral to the medial epicondyle of the humerus. Deeper palpation is required (compared to radial pulse palpation) due to the location of the brachial artery.

Types of pulse character

- Normal

- Slow-rising (associated with aortic stenosis)

- Bounding (associated with aortic regurgitation and also CO2 retention)

- Thready (associated with intravascular hypovolaemia in conditions such as sepsis)

Blood pressure

Measure the blood pressure

Measure the patient’s blood pressure in both arms (see our blood pressure guide for more details).

Blood pressure abnormalities

Blood pressure abnormalities may include:

- Hypertension: blood pressure of greater than or equal to 140/90 mmHg if under 80 years old or greater than or equal to 150/90 mmHg if you’re over 80 years old).

- Hypotension: blood pressure of less than 90/60 mmHg.

- Narrow pulse pressure: less than 25 mmHg of difference between the systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Causes include aortic stenosis, congestive heart failure and cardiac tamponade.

- Wide pulse pressure: more than 100 mmHg of difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Causes include aortic regurgitation and aortic dissection.

- Difference between arms: more than 20 mmHg difference in blood pressure between each arm is abnormal and may suggest aortic dissection.

Carotid pulse

The carotid pulse can be located between the larynx and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Auscultate the carotid artery

Prior to palpating the carotid artery, you need to auscultate the vessel to rule out the presence of a bruit. The presence of a bruit suggests underlying carotid stenosis, making palpation of the vessel potentially dangerous due to the risk of dislodging a carotid plaque and causing an ischaemic stroke.

Place the diaphragm of your stethoscope between the larynx and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle over the carotid pulse and ask the patient to take a deep breath and then hold it whilst you listen.

Be aware that at this point in the examination, the presence of a ‘carotid bruit’ may, in fact, be a radiating cardiac murmur (e.g. aortic stenosis).

Palpate the carotid pulse

If no bruits were identified, proceed to carotid pulse palpation:

1. Ensure the patient is positioned safely on the bed, as there is a risk of inducing reflex bradycardia when palpating the carotid artery (potentially causing a syncopal episode).

2. Gently place your fingers between the larynx and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to locate the carotid pulse.

3. Assess the character (e.g. slow-rising in aortic stenosis) and volume of the pulse.

Jugular venous pressure (JVP)

In a focused examination for aortic stenosis, assessment of the JVP is performed to screen for evidence of right heart failure, which commonly occurs secondary to left heart failure (e.g. due to excessive afterload in aortic stenosis).

Jugular venous pressure (JVP) provides an indirect measure of central venous pressure. This is possible because the internal jugular vein (IJV) connects to the right atrium without any intervening valves, resulting in a continuous column of blood. The presence of this continuous column of blood means that changes in right atrial pressure are reflected in the IJV (e.g. raised right atrial pressure results in distension of the IJV).

The IJV runs between the medial end of the clavicle and the ear lobe, under the medial aspect of the sternocleidomastoid, making it difficult to visualise (its double waveform pulsation is, however, sometimes visible due to transmission through the sternocleidomastoid muscle).

Because of the inability to easily visualise the IJV, it’s tempting to use the external jugular vein (EJV) as a proxy for assessment of central venous pressure during clinical assessment. However, because the EJV typically branches at a right angle from the subclavian vein (unlike the IJV which sits in a straight line above the right atrium) it is a less reliable indicator of central venous pressure.

Measure the JVP

1. Position the patient in a semi-recumbent position (at 45°).

2. Ask the patient to turn their head slightly to the left.

3. Inspect for evidence of the IJV, running between the medial end of the clavicle and the ear lobe, under the medial aspect of the sternocleidomastoid (it may be visible between just above the clavicle between the sternal and clavicular heads of the sternocleidomastoid. The IJV has a double waveform pulsation, which helps to differentiate it from the pulsation of the external carotid artery.

4. Measure the JVP by assessing the vertical distance between the sternal angle and the top of the pulsation point of the IJV (in healthy individuals, this should be no greater than 3 cm).

Causes of a raised JVP

A raised JVP indicates the presence of venous hypertension. Cardiac causes of a raised JVP include:

- Right-sided heart failure: commonly caused by left-sided heart failure (e.g. secondary to aortic stenosis). Pulmonary hypertension is another cause of right-sided heart failure, often occurring due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or interstitial lung disease.

- Tricuspid regurgitation: causes include infective endocarditis and rheumatic heart disease.

- Constrictive pericarditis: often idiopathic, but rheumatoid arthritis and tuberculosis are also possible underlying causes.

Eyes

Inspect the eyes for signs relevant to aortic stenosis

- Corneal arcus: a hazy white, grey or blue opaque ring located in the peripheral cornea, typically occurring in patients over the age of 60. In older patients, the condition is considered benign, however, its presence in patients under the age of 50 suggests underlying hypercholesterolaemia (increased risk of aortic stenosis).

- Xanthelasma: yellow, raised cholesterol-rich deposits around the eyes associated with hypercholesterolaemia (increased risk of aortic stenosis).

Close inspection of the chest

Closely inspect the anterior chest

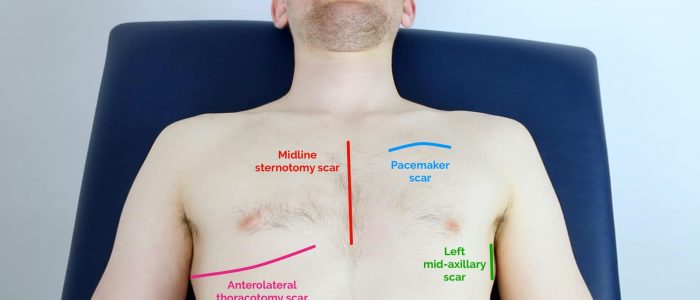

Look for clinical signs that may provide clues as to the patient’s past medical/surgical history:

- Scars suggestive of previous thoracic surgery: see the thoracic scars section below.

- Pectus excavatum: a caved-in or sunken appearance of the chest.

- Pectus carinatum: protrusion of the sternum and ribs.

- Visible pulsations: a forceful apex beat may be visible secondary to underlying ventricular hypertrophy (e.g. aortic stenosis).

Thoracic scars

- Median sternotomy scar: located in the midline of the thorax. This surgical approach is used for cardiac valve replacement and coronary artery bypass grafts (CABG).

- Anterolateral thoracotomy scar: located between the lateral border of the sternum and the mid-axillary line at the 4th or 5th intercostal space. This surgical approach is used for minimally invasive cardiac valve surgery.

- Infraclavicular scar: located in the infraclavicular region (on either side). This surgical approach is used for pacemaker insertion.

- Left mid-axillary scar: this surgical approach is used for the insertion of a subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

Palpation

Palpate the chest to assess the location of the apex beat and to identify heaves or thrills.

Apex beat

- Palpate the apex beat with your fingers placed horizontally across the chest.

- In healthy individuals, it is typically located in the 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line. Ask the patient to lift their breast to allow palpation of the appropriate area if relevant.

- Displacement of the apex beat from its usual location can occur due to ventricular hypertrophy.

- The apex beat in aortic stenosis may be displaced due to ventricular hypertrophy.

Heaves

- A parasternal heave is a precordial impulse that can be palpated.

- Place the heel of your hand parallel to the left sternal edge (fingers vertical) to palpate for heaves.

- If heaves are present you should feel the heel of your hand being lifted with each systole.

- Parasternal heaves are typically associated with right ventricular hypertrophy.

Thrills

- A thrill is a palpable vibration caused by turbulent blood flow through a heart valve (a thrill is a palpable murmur).

- You should assess for a thrill across each of the heart valves in turn (see valve locations below).

- To do this place your hand horizontally across the chest wall, with the flats of your fingers and palm over the valve to be assessed.

- In the context of aortic stenosis, a systolic thrill may be palpable over the aortic valve.

Valve locations

- Mitral valve: 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line.

- Tricuspid valve: 4th or 5th intercostal space at the lower left sternal edge.

- Pulmonary valve: 2nd intercostal space at the left sternal edge.

- Aortic valve: 2nd intercostal space at the right sternal edge.

Auscultation

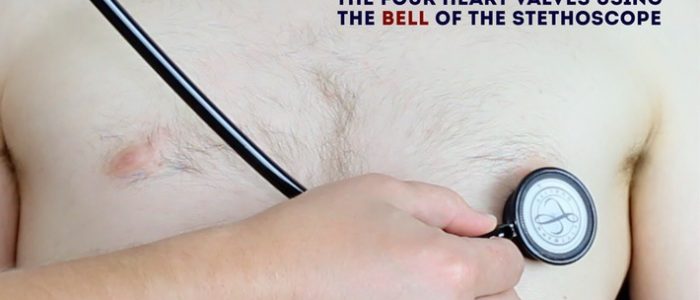

Auscultate the four heart valves

A systematic routine will ensure you remember all the steps whilst giving you several chances to listen to each valve area. Your routine should avoid excess repetition whilst each step should ‘build’ upon the information gathered by the previous steps. Ask the patient to lift their breast to allow auscultation of the appropriate area if relevant.

1. Palpate the carotid pulse to determine the first heart sound.

2. Auscultate ‘upwards’ through the valve areas using the diaphragm of the stethoscope whilst continuing to palpate the carotid pulse:

- Mitral valve: 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line.

- Tricuspid valve: 4th or 5th intercostal space at the lower left sternal edge.

- Pulmonary valve: 2nd intercostal space at the left sternal edge.

- Aortic valve: 2nd intercostal space at the right sternal edge.

3. Repeat auscultation across the four valves with the bell of the stethoscope.

Accentuation manoeuvres

Auscultate the carotid arteries using the diaphragm of the stethoscope whilst the patient holds their breath to listen for radiation of an ejection systolic murmur caused by aortic stenosis.

Typical findings in aortic stenosis

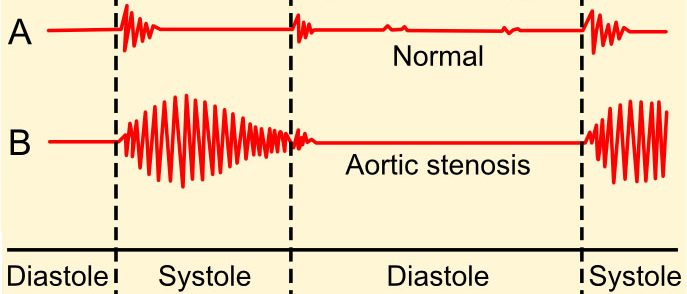

Aortic stenosis is associated with an ejection systolic murmur heard loudest over the aortic valve. The murmur is described as having a ‘crescendo-decrescendo’ quality (it appears as diamond-shaped on a phonogram). The murmur of aortic stenosis commonly radiates to the carotid arteries.

Levine murmur grading scale

Grade 1: a very faint murmur which is only audible during prolonged auscultation.

Grade 2: a faint murmur, immediately audible with a stethoscope.

Grade 3: a loud murmur with NO thrill.

Grade 4: a loud murmur WITH a thrill.

Grade 5: a loud murmur WITH a thrill, heard with only half of the stethoscope touching the chest.

Grade 6: a loud murmur WITH a thrill, heard WITHOUT the stethoscope touching the chest.

You will not be expected to grade a murmur, but it is useful to have a basic understanding of the scale.

Final steps

Posterior chest wall

Auscultation

Auscultate the lung fields posteriorly:

- Coarse crackles are suggestive of pulmonary oedema (e.g. secondary to left ventricular failure).

- Absent air entry and stony dullness on percussion are suggestive of an underlying pleural effusion (e.g. secondary to left ventricular failure).

Sacral oedema

Inspect and palpate the sacrum for evidence of pitting oedema.

Legs

Inspect and palpate the patient’s ankles for evidence of pitting pedal oedema (associated with right ventricular failure).

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

Example summary

“Today I examined Mr Smith, a 64-year-old male. On general inspection, the patient appeared comfortable at rest and there were no objects or medical equipment around the bed of relevance.”

“The hands had no peripheral stigmata of cardiovascular disease and were symmetrically warm, with a normal capillary refill time.”

“The pulse was regular with a slow-rising character.”

“On inspection of the face, corneal arcus was noted.”

“Assessment of the JVP did not reveal any abnormalities.”

“Closer inspection of the chest did not reveal any scars or chest wall abnormalities. The apex beat was palpable in the 5th intercostal space, in the mid-clavicular line. A thrill was noted over the aortic region.”

“Auscultation of the praecordium revealed an ejection systolic murmur in the aortic region with radiation to the carotid arteries.”

“There was no evidence of peripheral oedema and lung fields were clear on auscultation.”

“In summary, these findings are consistent with a diagnosis of aortic stenosis.”

“For completeness, I would like to perform the following further assessments and investigations.”

Further assessments and investigations

Suggest further assessments and investigations to the examiner:

- Record a 12-lead ECG: to look for evidence of arrhythmias or myocardial ischaemia.

- Request echocardiography: to confirm a diagnosis of aortic stenosis.

References

- Madhero88. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Phonogram. Licence: CC BY-SA 3.0.