- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This guide discusses how to approach performing a focused acromegaly examination on a patient in an OSCE setting.

In OSCE scenarios, you may be asked to perform a focused examination to determine the presence (or absence) of a certain condition. It is important to be able to confidently elicit the main diagnostic signs of the condition. In order to do this, you need to be comfortable with the relevant basic system examination (i.e. for an acromegaly examination you need to be able to perform assessments such as a full examination of the eyes and vision).

Background

Acromegaly is a disorder of excessive growth hormone (GH) which is produced in the anterior pituitary gland. This most commonly occurs secondary to a pituitary adenoma. Too much GH causes a wide range of features associated with its complex physiological function, including excessive soft-tissue growth. Acromegaly most commonly presents in patients in their 30s.

Clinical features of acromegaly include:

- Coarse facial features such as prognathism

- Enlarged hands, feet, and tongue

- Headaches

- Thickened skin of the face and hands

- Hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating)

- Visual field defects: classically a bitemporal hemianopia

- Arthropathy

- Nerve compression symptoms, typically carpel tunnel syndrome

Acromegaly can further cause a variety of complications including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiomyopathy, and sleep apnoea.

Anterior pituitary hormones

The mnemonic FLAT PEG can be used to recall the hormones released by the anterior pituitary:

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

- Luteinising hormone (LH)

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Prolactin

- Endorphins

- Growth hormone (GH)

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language.

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Ask if the patient if they have any pain before proceeding with clinical examination.

General inspection

Significant information can be obtained from inspection in patients with acromegaly, so a general inspection is a vital part of the assessment.

Clinical signs

Perform a brief general inspection of the patient, looking for clinical signs suggestive of acromegaly such as:

- Facial features: coarse features, such as prominent supraorbital ridges and prognathism, may be indicative of acromegaly.

- Hands and feet: may be enlarged.

- Skin: may display thickening in the hands and face and excess sweating or oiliness in acromegaly.

- Posture: patients with acromegaly can present with signs of osteoarthritis, especially in the weight-bearing joints (knees and hips).

- Hair growth: hirsutism in women and hypertrichosis may occur.

- Skin tags: acromegaly can cause an increase in the number of skin tags.

- Gait: acromegaly can cause a rolling gait or varus deformity.

- Clothes: clothes or jewellery may appear tight if significant weight gain has occurred.

Objects and equipment

Look for objects or equipment on or around the patient that may provide useful insights into their medical history and current clinical status:

- Medical equipment: note any oxygen delivery devices and ECG leads.

- Mobility aids: items such as walking aids give an indication of the patient’s current mobility status.

- Vital signs: charts on which vital signs are recorded will give an indication of the patient’s current clinical status and how their physiological parameters have changed over time.

- Prescriptions: prescribing charts or personal prescriptions can provide useful information about the patient’s recent medications.

Hands

Inspection

The following signs may be seen on close inspection of the hands:

- Enlargement: grossly increased size of the hands may be assessed by comparing your hands to the patient’s, accounting for natural size differences.

- Wasting: thenar wasting (Figure 1) can indicate untreated carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Scars: carpal tunnel release scar (Figure 2) may indicate previous median nerve compression.

- Skin changes: skin thickening and excess sweating can occur in acromegaly.

- Finger pricks: finger prick marks on the tips of the fingers may indicate diabetes, which is linked to acromegaly.

Palpation

Assess for thickening of the patient’s skin by pinching the skin overlaying the third metacarpophalangeal joint. This can be compared with your own hand’s skin to detect any differences.

Pulses and blood pressure

Radial pulse

Palpate the patient’s radial pulse, located at the radial side of the wrist, with the tips of your index and middle fingers aligned longitudinally over the course of the artery.

Once you have located the radial pulse, assess the rate and rhythm.

Blood pressure

Offer to measure the patient’s blood pressure (see our blood pressure guide for more details).

A comprehensive blood pressure assessment should also include lying and standing blood pressure.

In an OSCE station, you are unlikely to have to carry out a thorough blood pressure assessment due to time restraints, however, you should demonstrate that you have an awareness of what this would involve.

Special tests

Tinel’s test

Tinel’s test is used to identify median nerve compression and can be useful in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome.

To perform the test, simply tap over the carpal tunnel with your finger.

Interpretation

If the patient develops tingling in the thumb and radial two and a half fingers, this is suggestive of median nerve compression.

Phalen’s test

If the history or examination findings are suggestive of carpal tunnel syndrome, Phalen’s test may be used to further support the diagnosis.

Ask the patient to hold their wrist in maximum forced flexion (pushing the dorsal surfaces of both hands together) for 60 seconds.

Interpretation

If the patient’s symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome are reproduced, then the test is positive (e.g. burning, tingling or numb sensation in the thumb, index, middle and ring fingers).

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common form of nerve compression found in acromegaly. It occurs as a result of compression of the median nerve as it traverses through the wrist via the carpal tunnel, which is usually due to excess local soft-tissue growth.

Typical clinical features include pain and paraesthesia in the distribution of the median nerve (the thumb, index finger, middle finger, and lateral half of the ring finger). Grip weakness can also develop secondary to wasting of the thenar muscles, which receive motor innervation from the median nerve.

Axillae

Inspection

Whilst supporting the patient’s arm, inspect each axilla for the following:

- Acanthosis nigricans (Figure 3): darkening (hyperpigmentation) and thickening (hyperkeratosis) of the axillary skin which can be benign (most commonly in dark-skinned individuals) or associated with insulin resistance (e.g. type 2 diabetes mellitus) as a complication of acromegaly.

- Hypertrichosis: increased hair growth can occur as a result of the effects of growth hormone.

Neck

Jugular venous pressure (JVP)

Jugular venous pressure (JVP) provides an indirect measure of central venous pressure. This is possible because the internal jugular vein (IJV) connects to the right atrium without any intervening valves, resulting in a continuous column of blood. The presence of this continuous column of blood means that changes in right atrial pressure are reflected in the IJV (e.g. raised right atrial pressure results in distension of the IJV).

The IJV runs between the medial end of the clavicle and the ear lobe, under the medial aspect of the sternocleidomastoid, making it difficult to visualise (its double waveform pulsation is, however, sometimes visible due to transmission through the sternocleidomastoid muscle).

Because of the inability to easily visualise the IJV, it’s tempting to use the external jugular vein (EJV) as a proxy for the assessment of central venous pressure during clinical assessment. However, because the EJV typically branches at a right angle from the subclavian vein (unlike the IJV which sits in a straight line above the right atrium) it is a less reliable indicator of central venous pressure.

See our guide to jugular venous pressure (JVP) for more details.

Measure the JVP

1. Position the patient in a semi-recumbent position (at 45°).

2. Ask the patient to turn their head slightly to the left.

3. Inspect for evidence of the IJV, running between the medial end of the clavicle and the ear lobe, under the medial aspect of the sternocleidomastoid (it may be visible between just above the clavicle between the sternal and clavicular heads of the sternocleidomastoid. The IJV has a double waveform pulsation, which helps to differentiate it from the pulsation of the external carotid artery.

4. Measure the JVP by assessing the vertical distance between the sternal angle and the top of the pulsation point of the IJV (in healthy individuals, this should be no greater than 3 cm).

JVP and acromegaly

Patients with acromegaly can have a raised JVP because a complication of the condition is acromegalic cardiomyopathy, which causes progressive cardiac dysfunction and therefore a backup of blood into the venous system if advanced enough.

Thyroid palpation

Acromegaly can cause thyroid nodules or, less commonly, a globally enlarged thyroid gland.

Palpate each of the thyroid’s lobes and the isthmus.

1. Stand behind the patient and ask them to tilt their chin slightly downwards to relax the muscles of the neck to aid palpation of the thyroid gland.

2. Place the three middle fingers of each hand along the midline of the neck below the chin.

3. Locate the upper edge of the thyroid cartilage (“Adam’s apple”) with your fingers.

4. Move your fingers inferiorly until you reach the cricoid cartilage. The first two rings of the trachea are located below the cricoid cartilage and the thyroid isthmus overlies this area.

5. Palpate the thyroid isthmus using the pads of your fingers.

6. Palpate each lobe of the thyroid in turn by moving your fingers out laterally from the isthmus.

7. Ask the patient to swallow some water, whilst you feel for the symmetrical elevation of the thyroid lobes (asymmetrical elevation may suggest a unilateral thyroid mass).

8. Ask the patient to protrude their tongue (if a mass represents a thyroglossal cyst, you will feel it rise during tongue protrusion).

Face

General appearance

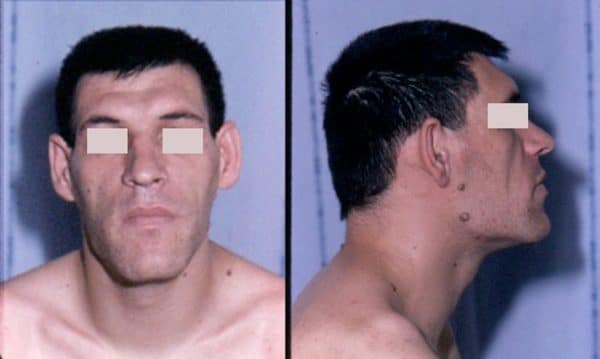

Inspect the general appearance face for coarse features associated with acromegaly:

- Frontal bossing: a prominent or protruding brow can occur with excess GH (Figure 4).

- Large nose, ears, and lower lip: aspects of soft-tissue overgrowth.

- Prognathism: overgrowth of the jaw can lead to a mandibular protrusion (Figure 5).

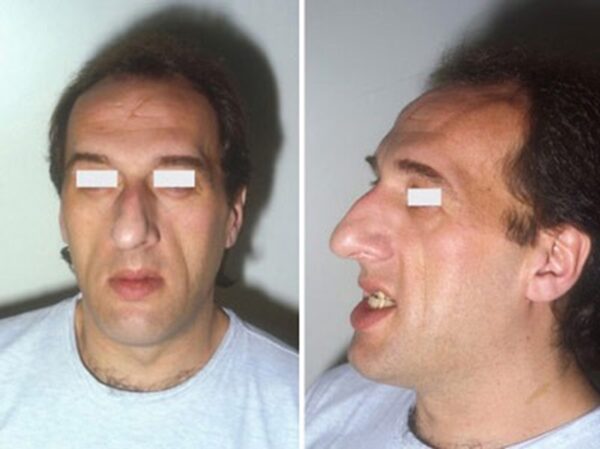

Mouth

Inspect the inside the mouth face for the following:

- Macroglossia: tongue enlargement may cause the tongue to appear large for the mouth or even cause visible partial airway obstruction in extreme cases.

- Wide spaced teeth: growth of the soft palate may cause interdental separation of the lower jaw (Figure 6).

- Prognathism: overgrowth of the jaw may only be discernible on closer inspection.

Visual fields

This method of visual field assessment relies on comparing the patient’s visual field with your own. Therefore, for it to work:

- You need to position yourself, the patient, and the target correctly (see details below)

- You need to have normal visual fields and a normal-sized blindspot

Visual field assessment

1. Sit directly opposite the patient, at a distance of around 1 metre.

2. Ask the patient to cover one eye with their hand.

3. If the patient covers their right eye, you should cover your left eye (mirroring the patient).

4. Ask the patient to focus on part of your face (e.g. nose) and not move their head or eyes during the assessment. You should do the same and focus your gaze on the patient’s face.

5. As a screen for central visual field loss or distortion, ask the patient if any part of your face is missing or distorted. A formal assessment can be completed with an Amsler chart.

6. Position the hatpin (or another visual target) at an equal distance between you and the patient (this is essential for the assessment to work).

7. Assess the patient’s peripheral visual field by comparing it to your own and using the visual target. Start from the periphery and slowly move the target towards the centre, asking the patient to report when they first see it. If you are able to see the target but the patient cannot, this would suggest the patient has a reduced visual field.

8. Repeat this process for each visual field quadrant, then repeat the entire process for the other eye.

9. Document your findings.

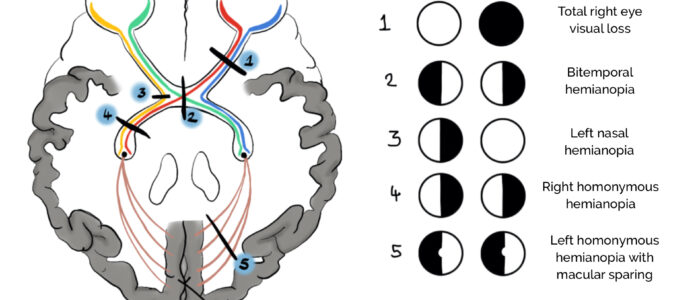

Visual field deficits in acromegaly

Acromegaly is classically associated with bitemporal hemianopia. This refers to a loss of the temporal vision (peripheral to the midline) in both eyes.

It tends to progress first from a bilateral upper temporal quadrantanopia to later involve the lower temporal fields. This may occur due to a pituitary adenoma compressing the optic chiasm from below. The optic chiasm is where the tracts for the temporal vision cross over onto the other side of the brain, so compression spares the nasal vision.

Because the pituitary gland underlies the optic chiasm, the lower part of the optic chiasm is compressed first. As everything in the optic tract is reversed, inferior optic chiasm compression results in an upper temporal visual field defect. Therefore, the upper temporal field quadrants tend to be affected first, which may then progress to include the lower temporal field quadrants as the superior optic chiasm becomes compressed, leading to bitemporal hemianopia.

Other assessments

Proximal myopathy

Although the pathophysiology isn’t entirely clear, it is suspected the combined effects of GH and the endocrine complications of acromegaly can cause proximal myopathy despite the increased muscle mass associated with the condition. Patients may develop wasting of their proximal musculature, causing difficulties in tasks such as standing from a sitting position.

To screen for proximal myopathy, ask the patient to stand from a sitting position with their arms crossed (to minimise their ability to mask proximal muscle weakness). Make sure to stand close to the patient to prevent them from falling. An inability to stand up suggests proximal muscle weakness.

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

Example summary

“Today I performed a focused acromegaly examination on a 34-year-old gentleman. On general inspection, the patient demonstrated marked facial features and large hands and feet.”

“The hands displayed thickened skin overlying the third metacarpophalangeal joint as well as excessive sweating. Phalen’s and Tinel’s tests were negative. The axillae were unremarkable.”

“Assessment of the JVP did not reveal any abnormalities, with a measurement of around 3cm.”

“Palpation of the thyroid gland revealed palpable thyroid nodules.”

“Inspection of the face revealed marked facial features including prognathism. On further inspection of the mouth, there was evident interdental separation of the lower mandible, as well as macroglossia.”

“Assessment of the visual fields by confrontation revealed a gross bitemporal hemianopia.”

“There was no proximal myopathy evident as the patient was able to stand without the use of the arms from a seated position.”

“For completeness, I would like to perform the following further assessments and investigations.”

Further assessments and investigations

- Perform a full cardiovascular examination including measuring blood pressure: to identify cardiovascular involvement including hypertension.

- GH and IGF-1 blood testing: to help guide diagnosis as IGF-1 doesn’t vary according to the time of day as GH does, but still tests for GH excess.

- Pituitary MRI: to check for the presence of an adenoma.

- Thyroid status examination and thyroid function tests (TSH, T3, T4): to assess for thyroid involvement.

- Bedside capillary blood glucose: to test for diabetes.

- Serum HbA1c: to aid assessment of blood glucose control over the previous three months.

Reviewers

Professor John Wass

Professor of Endocrinology

Oxford University

Dr Andrew Lansdown

Consultant Endocrinology & Honorary Lecturer

University Hospital of Wales & Cardiff University School of Medicine

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Dr Harry Gouvas. Adapted by GeekyMedics. Thenar wasting. License: [Public domain]

- HenrykGerlach. Carpal tunnel release scars. License: [CC BY-SA 3.0]

- Madhero88. Acanthosis nigricans. Licence: [CC BY-SA 3.0]

- Philippe Chanson, Sylvie Salenave. Prominent facial features of a patient with acromegaly. License: [CC BY 2.0]

- Philippe Chanson, Sylvie Salenave. Mandibular overgrowth in a patient with acromegaly leading to prognathism. License: [CC BY 2.0)]

- Kenneth Yamanaka. Interdental separation in an acromegaly patient. License: [Public domain]