- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG) is an acute rise in intraocular pressure associated with narrowing of the anterior chamber angle of the eye (the angle between the iris and cornea) causing optic nerve damage and sight loss.

The incidence of AACG in the United Kingdom is approximately 2 cases per 100,000 people per year.1

Aetiology

Anatomy

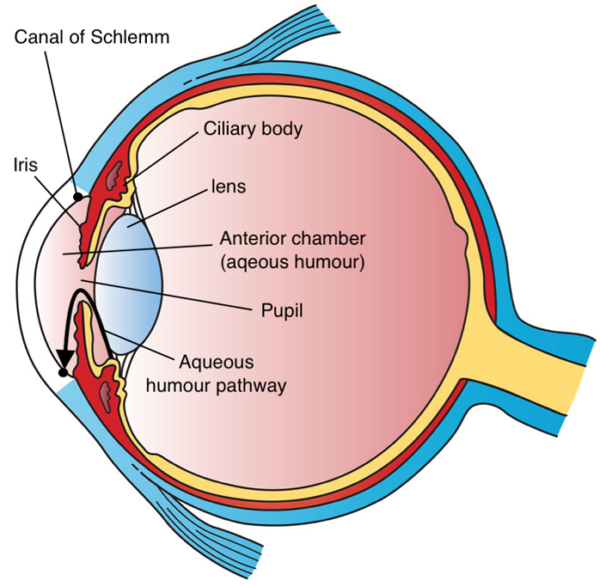

The aqueous humour supplies nutrients to the cornea and lens. It is produced by the ciliary body and travels through the pupil into the anterior chamber (the area between the iris and cornea).

Aqueous humour drains out of the anterior chamber through the trabecular meshwork and flows into the canal of Schlemm (Figure 1). The normal intraocular pressure (IOP) is maintained between 11-21mmHg.

Pathophysiology

AACG occurs in anatomically pre-disposed individuals with shorter eye lengths and shallower anterior chambers. The vast majority of these individuals do not experience angle closure attacks and the risk is small at 1 in 1000 per year.3

In AACG, there is reduced drainage of aqueous humour due to anterior chamber angle narrowing from irido-trabecular contact. This is mediated by a ‘pupillary block’ – contact between the iris and the lens when the iris is in a mid-dilated position. This causes the peripheral iris to bow forward blocking the drainage angle, with subsequent rapid rise in IOP.

Risk factors

Risk factors for AACG include:

- Increasing age: particularly 6th to 7th decade of life

- Female sex: women have a three times greater risk than men

- East Asian ethnicity

- Family history

- Anatomical predisposition: including short eyeball length and hypermetropia (longsightedness)

Pupil mid-dilation can cause AACG by precipitating pupillary block in those at risk.

Pupil mid-dilation can be caused by being in a dark room or the use of certain medications such as anticholinergics (e.g. oxybutynin), antidepressants (SSRIs and TCAs) or pupil-dilating drops (e.g. tropicamide). Topiramate use has been associated with bilateral AACG.

Clinical features

AACG is an important differential diagnosis to consider in any patient presenting with a painful red eye.

History

AACG symptoms tend to develop over hours to days. Since pupil mid-dilation can trigger AACG, the patient may have been in a dark room when symptoms began or may be taking medications that cause pupil dilation.

Typical symptoms of AACG include:

- Unilateral severe eye pain or headache that may cause nausea and vomiting.

- Profound reduction in visual acuity or visual loss

- Rainbow coloured haloes around bright lights

Clinical examination

As a result of the rapid rise in intraocular pressure, the eye appears red and is hard.

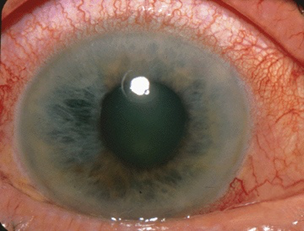

Raised intraocular pressure also causes corneal oedema giving the cornea a hazy appearance (Figure 2). The pupil is often fixed in a mid-dilated position and does not react to light.

Typical clinical findings in AACG include:

- Unilateral conjunctival injection

- Diffusely hazy cornea limiting view of the iris and pupil

- A fixed, non-reactive, mid-dilated pupil

- Very high IOP: this is always >30mmHg but can be as high as 60-80mmHg.

High IOP can be confirmed by asking the patient to close their eye and gently palpating using the tips of both index fingers. An eye with very high IOP will feel ‘hard’ on palpation.

Differential diagnoses

For more information on differential diagnoses, see the Geeky Medics guide to the painful red eye.

Investigations

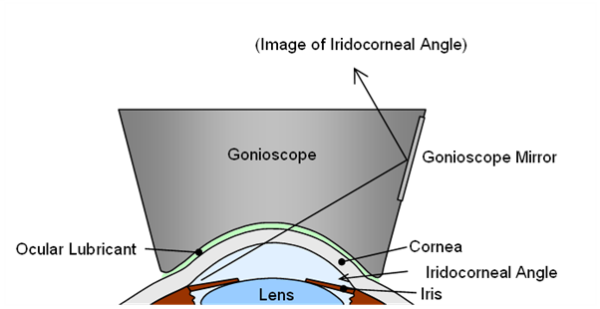

Relevant investigations for AACG include gonioscopy and tonometry.

Gonioscopy is the gold standard investigation for assessing the angle between the iris and cornea (Figure 3). Gonioscopy is mandatory in establishing a diagnosis of angle closure.

Tonometry is used to measure intraocular pressure. In AACG, intraocular pressure is typically >30mmHg.

The gold standard measurement of tonometry in AACG is Goldmann applanation tonometry, which calculates intraocular pressure by assessing the force required to flatten a fixed area of the cornea. This method requires considerable training to use.

Other tonometers, such as the iCare or Tono-Pen® require minimal training and are portable.

Management

AACG is sight-threatening and a true ophthalmic emergency.

Conservative measures that can be initiated by the non-specialist include oral analgesics and anti-emetics. The patient can be laid flat on their back (gravity helps bring the lens away and open the anterior chamber angle).

Specialist acute management of AACG includes:

- Systemic pressure-reducing agents: acetazolamide (IV/oral)

- Topical pressure-reducing agents (e.g. beta-blockers)

- Topical steroids to reduce inflammation

- Peripheral iridotomy (a laser hole through the iris) to allow a separate route for aqueous drainage other than through the pupil

Undergraduate medical textbooks frequently state that topical pilocarpine is a mainstay of AACG treatment. In clinical practice, the use of pilocarpine is nuanced and may even aggravate certain aetiologies of AACG.

Complications

Complications of AACG include:

- Sight loss

- Central or branch retinal vein occlusion

- Repeated episodes of AACG

Key points

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG) is an acute rise in intraocular pressure associated with narrowing of the anterior chamber angle of the eye.

- The vast majority of patients anatomically predisposed to angle closure will not develop an attack of AACG

- AACG is sight-threatening and should be considered in any patient presenting with an acutely painful red eye.

- Risk factors include increasing age, East Asian ethnicity, female sex and hypermetropia.

- AACG can be precipitated by inducing pupil mid-dilation from being in a dark room or the use of certain medications.

- Typical symptoms include headache, nausea and vomiting and visual changes (e.g. blurred vision or halos around lights).

- Typical clinical findings include a red-eye associated with a fixed mid-dilated pupil and corneal haze.

- Immediate referral to ophthalmology and early initiation of intraocular pressure lowering treatment is key for preventing sight loss.

- Complications include sight loss, retinal vein occlusion and recurrence of AACG.

Reviewer

Dr Sahib Tuteja

Opthalmology trainee

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Royal College of Ophthalmologists. The Management Of Angle-Closure Glaucoma. Available from: [LINK]

- Holly Fischer (modified by Jonathan Malcolm). Three Main Layers of the Eye. License: [CC BY].

- He M, Jiang Y, Huang S, Chang DS, Munoz B, Aung T, Foster PJ, Friedman DS. Laser peripheral iridotomy for the prevention of angle closure: a single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 Apr 20;393(10181):1609-1618. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32607-2. Epub 2019 Mar 14. PMID: 30878226.

- Jonathan Trobe. Acute Angle Closure-glaucoma. License: [CC BY].

- Mick Lucas. Gonioscopy. License: [CC BY].

- Salmon, J. F. (2019). Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach (9th ed.). Elsevier.