- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

This guide provides an overview of the recognition and immediate management of asthma using an ABCDE approach.

The ABCDE approach is used to systematically assess an acutely unwell patient. It involves working through the following steps:

- Airway

- Breathing

- Circulation

- Disability

- Exposure

Each stage of the ABCDE approach involves clinical assessment, investigations and interventions. Problems are addressed as they are identified, and the patient is re-assessed regularly to monitor their response to treatment.

This guide has been created to assist healthcare students in preparing for emergency simulation sessions as part of their training. It is not intended to be relied upon for patient care.

Background

Asthma is characterised by paroxysmal and reversible airway obstruction. The disease involves bronchospasm and excessive production of secretions.

An acute asthma exacerbation is characterised by rapidly worsening asthma symptoms, including cough, shortness of breath and wheezing. An asthma exacerbation can be life-threatening, so early recognition and appropriate management are paramount.

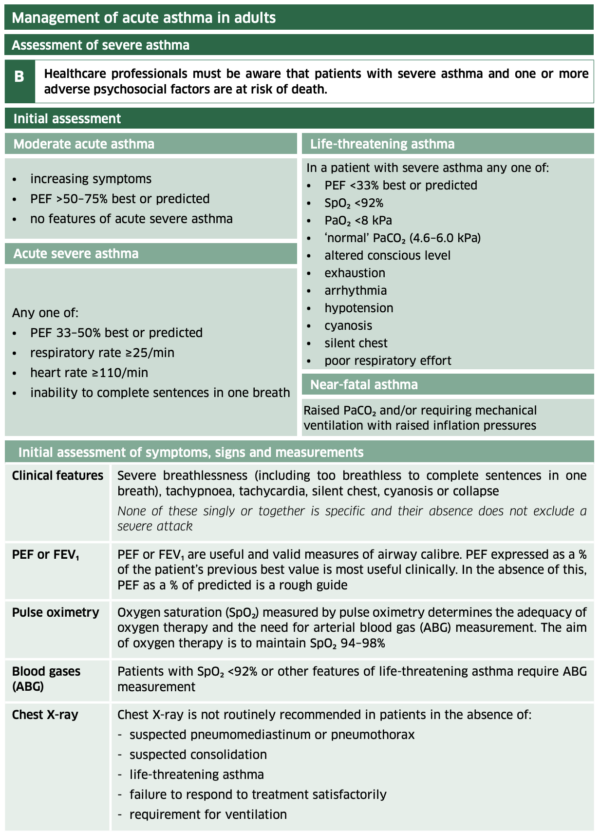

Asthma severity grading

Moderate asthma exacerbation

Clinical features of moderate asthma exacerbation include:

- Increasing asthma symptoms

- PEFR >50-70% of best or predicted

- No features of acute severe asthma

Acute severe asthma exacerbation

Clinical features of severe asthma exacerbation include any one of the following (in individuals > 12 years old):

- PEFR 33-50% of best or predicted

- Respiratory rate greater or equal to 25 breaths/min

- Pulse greater or equal to 110 beats/min

- Inability to complete sentences in one breath

Life-threatening asthma exacerbation

Clinical features of life-threatening asthma exacerbation include any one of the following in someone with severe asthma:

- PEFR <33% of best or predicted

- Oxygen saturation <92%

- Silent chest

- Cyanosis

- Poor respiratory effort

- Bradycardia

- Hypotension

- Dysrhythmia

- Confusion

- Exhaustion

- Coma

Near-fatal asthma exacerbation

Raised PaCO2 and/or requiring mechanical ventilation with raised inflation pressures.

Summary of BTS guidelines

Tips before you begin

General tips for applying an ABCDE approach in an emergency setting include:

- Treat problems as you discover them and re-assess after every intervention

- Remember to assess the front and back of the patient when carrying out your assessment (e.g. looking underneath the patient’s legs or at their back for non-blanching rashes or bleeding)

- If the patient loses consciousness and there are no signs of life, put out a crash call and commence CPR

- Make use of the team around you by delegating tasks where appropriate

- All critically unwell patients should have continuous monitoring equipment attached

- If you require senior input, call for help early using an appropriate SBAR handover

- Review results as they become available (e.g. laboratory investigations)

- Use local guidelines and algorithms to manage specific scenarios (e.g. acute asthma)

- Any medications or fluids must be prescribed at the time (you may be able to delegate this to another staff member)

- Your assessment and management should be documented clearly in the notes; however, this should not delay management

Methodical approach

For each section of the ABCDE assessment (e.g. airway, breathing, circulation etc.), ask yourself:

- Have I checked the relevant observations for this section? (e.g. checking respiratory rate and SpO2 as part of your ‘breathing’ assessment)

- Have I examined the relevant parts of the system in this section? (e.g. peripheral perfusion, pulses, JVP, heart sounds, and peripheral oedema as part of your ‘circulation’ assessment)

- Have I requested relevant investigations based on my findings from the initial clinical assessment? (e.g. capillary blood glucose as part of your ‘disability’ assessment)

- Have I intervened to correct the issues I have identified? (e.g. administering IV fluids in response to fluid depletion/hypotension as part of your ‘circulation’ assessment)

Initial steps

Acute scenarios typically begin with a brief handover, including the patient’s name, age, background and the reason the review has been requested.

You may be asked to review a patient with asthma due to shortness of breath and/or wheeze.

Introduction

Introduce yourself to whoever has requested a review of the patient and listen carefully to their handover.

Preparation

Ensure the patient’s notes, observation chart, and prescription chart are easily accessible.

Ask for another clinical member of staff to assist you if possible.

Interaction

Introduce yourself to the patient, including your name and role.

Ask how the patient is feeling, as this may provide useful information about their current condition.

An inability to speak in full sentences indicates significant shortness of breath, and the patient requires urgent assessment and management. Do not delay performing an ABCDE assessment by attempting to take a detailed history of asthma.

Airway

Clinical assessment

Can the patient talk?

Yes: if the patient can talk, their airway is patent, and you can move on to the assessment of breathing.

No:

- Look for signs of airway compromise: angioedema, cyanosis, see-saw breathing, use of accessory muscles and stridor

- Listen for abnormal airway noises: stridor, snoring, gurgling

Interventions

Regardless of the underlying cause of airway obstruction, seek immediate expert support from an anaesthetist and the emergency medical team (often called the ‘crash team’). You can perform basic airway manoeuvres to help maintain the airway whilst awaiting senior input.

Head-tilt chin-lift manoeuvre

Open the patient’s airway using a head-tilt chin-lift manoeuvre:

- Place one hand on the patient’s forehead and the other under the chin

- Tilt the forehead back whilst lifting the chin forwards to extend the neck

- Inspect the airway for obvious obstruction. If an obstruction is visible within the airway, use a finger sweep or suction to try and remove it. Be careful not to push it further into the airway.

Jaw thrust

If the patient is suspected of having suffered significant trauma with potential spinal involvement, perform a jaw-thrust rather than a head-tilt chin-lift manoeuvre:

- Identify the angle of the mandible

- Place two fingers under the angle of the mandible (on both sides) and anchor your thumbs on the patient’s cheeks

- Lift the mandible forwards

Other interventions

Airway adjuncts are helpful and, in some cases, essential to maintain a patient’s airway. They should be used in conjunction with the manoeuvres mentioned above.

An oropharyngeal airway is a curved plastic tube with a flange on one end that sits between the tongue and hard palate to relieve soft palate obstruction. It should only be inserted in unconscious patients as it may induce gagging and aspiration in semi-conscious patients.

A nasopharyngeal airway is a soft plastic tube with a bevel at one end and a flange at the other. NPAs are typically better tolerated in partly or fully conscious patients than oropharyngeal airways.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Breathing

Clinical assessment

Observations

Review the patient’s respiratory rate:

- A normal respiratory rate is between 12-20 breaths per minute

- Tachypnoea is a common feature of asthma exacerbations and indicates significant respiratory compromise

- Bradypnoea in the context of hypoxia is a sign of impending respiratory failure and the need for urgent critical care review

Review the patient’s oxygen saturation (SpO2):

- A normal SpO2 range is 94-98% in healthy individuals and 88-92% in patients with COPD at high risk of CO2 retention

- Hypoxaemia (SpO2 <92%) is a feature of life-threatening asthma

See our guide to performing observations/vital signs for more details.

Inspection

Observe for evidence of respiratory distress, including using accessory muscles and cyanosis.

Tracheal position

Gently assess the position of the trachea, which should be central in healthy individuals:

- Tracheal deviation may suggest a tension pneumothorax

Percussion of the chest

Percuss the patient’s chest, listening to the resulting percussion note, which should be resonant in healthy individuals. Abnormal findings on percussion include:

- Areas of dullness may be associated with pleural effusion or lobar collapse

- Areas of hyper-resonance associated with pneumothorax

Auscultation

Auscultate the patient’s chest and identify any abnormalities such as:

- Wheeze is a common finding in asthma exacerbations (it can become less apparent with increasing airway obstruction)

- Reduced air entry (sometimes called a ‘silent chest’) is a concerning finding indicating significant airway compromise and a need for senior clinical input

- Absent air entry in a specific chest area may suggest underlying pneumothorax

Investigations and procedures

Arterial blood gas

Take an ABG if indicated (e.g. low SpO2) to quantify the degree of hypoxia.

Typical ABG findings in asthma include low PaO2 and low PaCO2. In the early stages of an asthma exacerbation, the patient is typically hyperventilating, which causes the PaCO2 to fall.

Remember, a ‘normal’ PaCO2 in an asthma exacerbation is not reassuring. A normal or raised PaCO2 is significantly concerning as this indicates that the patient is becoming tired and is failing to ventilate effectively. These patients need urgent discussion with a senior clinician and critical care.

Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR)

PEFR can be used to assess the severity of the patient’s asthma exacerbation and their subsequent response to treatment. However, PEFR recording should not delay the administration of oxygen and nebulised medications.

Chest X-ray

A chest X-ray may be useful in excluding other respiratory diagnoses (e.g. pneumothorax, pneumonia, pulmonary oedema). Chest X-ray should not delay the emergency management of acute asthma.

Interventions

Patient positioning

If the patient is conscious, sit them upright, which can help with oxygenation.

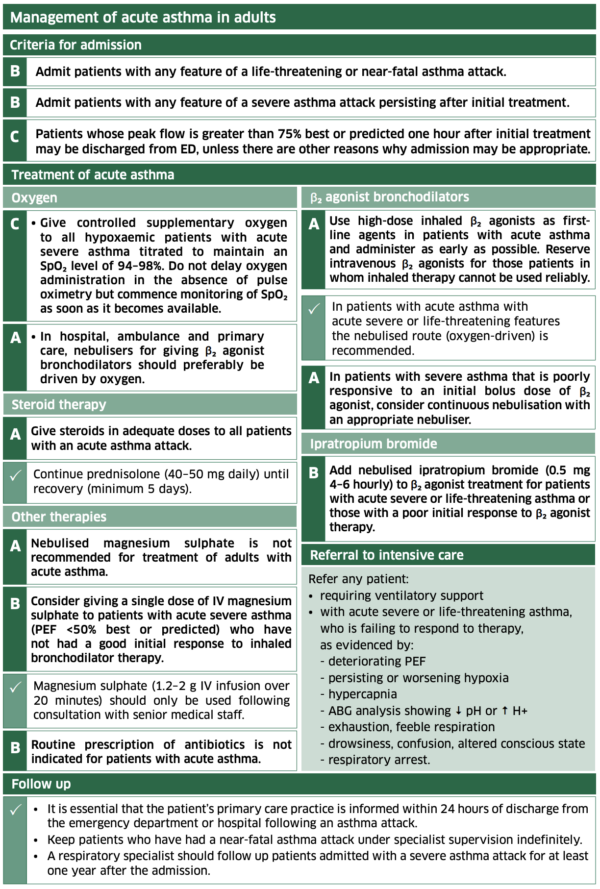

Oxygen

Administer oxygen to all critically unwell patients during your initial assessment. This typically involves using a non-rebreathe mask with an oxygen flow rate of 15L. You can then trial titrating oxygen levels downwards after your initial assessment.

Beta-2 agonist (salbutamol)

A high-dose inhaled beta-2 agonist (i.e. salbutamol) should be administered as a first-line treatment in the management of acute asthma:²

- Moderate asthma: use a pressurised multiple-dose inhaler (pMDI) plus spacer or oxygen-driven nebulisation to administer salbutamol

- Acute severe asthma: use oxygen-driven nebulisation to administer salbutamol

- Life-threatening asthma: use continuous oxygen-driven nebulisation to administer salbutamol

Repeat doses of salbutamol at 15-30 minute intervals or give continuous nebulised salbutamol at 5-10 mg/hour if there is an inadequate response to initial treatment.

See our guide to administering nebulised medication for more details.

Ipratropium bromide

Add nebulised ipratropium bromide (0.5 mg 4-6 hourly) to beta-2 agonist treatment for patients with acute severe or life-threatening asthma or those with a poor initial response to beta-2 agonist therapy.

Combining nebulised ipratropium bromide with a nebulised beta-2 agonist produces significantly greater bronchodilation than a beta-2 agonist alone.2

Corticosteroids

Steroids reduce mortality, relapses, subsequent hospital admission and the requirement for beta-2 agonist therapy. The earlier steroids are administered, the better the outcome.2

Administer steroids to all patients presenting with acute asthma (typically 40-50mg of oral prednisolone). If the oral route is unavailable (e.g. patient cannot swallow), intravenous hydrocortisone (100mg) can be used.

Continue prednisolone 40-50mg daily for at least five days after the exacerbation or until recovery.

Magnesium sulphate

There is evidence that magnesium sulphate has a bronchodilatory effect in adults.2

Consider giving a single dose of IV magnesium sulphate (1.2-2g infusion) to patients with:

- Acute severe asthma who have not had a good initial response to inhaled bronchodilator therapy

- Life-threatening or near-fatal asthma

Magnesium sulphate should only be used following consultation with a senior clinician.

Intravenous aminophylline

IV aminophylline should only be administered by senior clinician or in a critical care context. It is unlikely to produce additional bronchodilation and is associated with significant side effects (e.g. arrhythmias).

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not routinely used in acute asthma unless there is evidence of underlying infection.2

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Circulation

Clinical assessment

Pulse

Patients with acute asthma may be tachycardic, particularly if beta-agonists have been administered.

Blood pressure

Hypotension is a highly concerning feature of life-threatening asthma.

Capillary refill time

Capillary refill time may be prolonged in life-threatening asthma.

Fluid balance assessment

Calculate the patient’s fluid balance:

- Calculate the patient’s current fluid balance using their fluid balance chart (e.g. oral fluids, intravenous fluids, urine output, drain output, stool output, vomiting) to inform resuscitation efforts.

- Reduced urine output (oliguria) is typically defined as less than 0.5ml/kg/hour in an adult.

Investigations and procedures

Intravenous cannulation

Insert at least one wide-bore intravenous cannula (14G or 16G) and take blood tests as discussed below.

See our intravenous cannulation guide for more details.

Blood tests

Request a full blood count (FBC), urea & electrolytes (U&E) and liver function tests (LFTs) for all acutely unwell patients. In the context of asthma, also request:

- Inflammatory markers (CRP): to assess for evidence of inflammation/infection

ECG

An ECG should be performed in patients with persistent tachycardia or arrhythmias.

An ECG should not delay the emergency management of asthma.

Interventions

Fluid resuscitation

Hypovolaemic patients require fluid resuscitation:

- Administer a 500ml bolus Hartmann’s solution or 0.9% sodium chloride (warmed if available) over less than 15 mins

- Administer 250ml boluses in patients at increased risk of fluid overload (e.g. heart failure)

After each fluid bolus, reassess for clinical evidence of fluid overload (e.g. auscultation of the lungs, assessment of JVP).

Repeat administration of fluid boluses up to four times (e.g. 2000ml or 1000ml in patients at increased risk of fluid overload), reassessing the patient each time.

Seek senior input if the patient has a negative response (e.g. increased chest crackles) or isn’t responding adequately to repeated boluses (i.e. persistent hypotension).

See our fluid prescribing guide for more details on resuscitation fluids.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Disability

Clinical assessment

Consciousness

In asthma, a patient’s consciousness level may be reduced secondary to hypoxia.

Assess the patient’s level of consciousness using the ACVPU scale:

- Alert: the patient is fully alert

- Confusion: the patient has new onset confusion or worse confusion than usual

- Verbal: the patient makes some kind of response when you talk to them (e.g. words, grunt)

- Pain: the patient responds to a painful stimulus (e.g. supraorbital pressure)

- Unresponsive: the patient does not show evidence of any eye, voice or motor responses to pain

If a more detailed assessment of the patient’s level of consciousness is required, use the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).

Pupils

Assess the patient’s pupils:

- Inspect the size and symmetry of the patient’s pupils

- Assess direct and consensual pupillary responses

Brief neurological assessment

Perform a brief neurological assessment by asking the patient to move their limbs.

If a patient cannot move one or all of their limbs, this may be a sign of focal neurological impairment, which requires a more detailed assessment.

Drug chart review

Review the patient’s drug chart for medications which may cause neurological abnormalities (e.g. opioids, sedatives, anxiolytics).

Investigations and procedures

Blood glucose and ketones

Measure the patient’s capillary blood glucose level to screen for abnormalities (e.g. hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia).

A blood glucose level may already be available from earlier investigations (e.g. ABG, venepuncture).

The normal reference range for fasting plasma glucose is 4.0 – 5.8 mmol/l.

Hypoglycaemia is defined as a plasma glucose of less than 3.0 mmol/l. In hospitalised patients, a blood glucose ≤4.0 mmol/L should be treated if the patient is symptomatic.

If the blood glucose is elevated, check ketone levels which, if also elevated, may suggest a diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

See our blood glucose measurement, hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis guides for more details.

Interventions

Maintain the airway

Alert a senior clinician immediately if you have concerns about a patient’s consciousness level.

A GCS of 8 or below, or a P or U on the ACVPU scale, warrants urgent expert help from an anaesthetist. In the meantime, you should re-assess and maintain the patient’s airway, as explained in the airway section of this guide.

Correct hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia should always be considered in patients presenting with a reduced level of consciousness, regardless of whether they have diabetes. The management of hypoglycaemia involves the administration of glucose (e.g. oral or intravenous).

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Exposure

Exposing the patient during your assessment may be necessary. Remember to prioritise patient dignity and the conservation of body heat.

Clinical assessment

Temperature

Assess the patient’s temperature: fever may indicate an infective cause underlying the acute exacerbation of asthma.

Re-assessment

Make sure to re-assess the patient after any intervention.

Re-assessment and escalation

Re-assess the patient using the ABCDE approach to identify any changes in their clinical condition and assess the effectiveness of your previous interventions.

Any clinical deterioration should be recognised quickly and acted upon immediately.

Seek senior help if the patient shows no signs of improvement or if you have any concerns.

Escalation

Patients with asthma who are not responding to treatment, or those with life-threatening asthma, will require urgent critical care input to consider treatment escalation (e.g. intubation and ventilation).

Use an effective SBAR handover to communicate the key information to other medical staff.

Next steps

Take a history

Take a thorough history to identify risk factors for asthma and explore relevant medical history.

See our history taking guides for more details.

Review

Review the patient’s notes, charts and recent investigation results.

Review the patient’s current medications and check any regular medications are prescribed appropriately.

Discuss

Discuss the patient’s clinical condition with a senior clinician using an SBAR handover.

Questions which may need to be considered include:

- Are any further assessments or interventions required?

- Does the patient need a referral to HDU/ICU?

- Does the patient need reviewing by a specialist?

- Should any changes be made to the current management of their underlying condition(s)?

The next team of clinicians on shift should be informed of any acutely unwell patient.

Document

Document your ABCDE assessment, including history, examination, observations, investigations, interventions, and the patient’s response.

The ABCDE approach can also form the structure for documenting your assessment.

See our documentation guides for more details.

Reviewer

Dr Leah Williams

Doctor

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- British Thoracic Society/SIGN guidelines. Management of Acute Asthma in Adults. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. Acute asthma exacerbation. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Figure 1 and Figure 2. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). British guideline on the management of asthma. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2019. (SIGN publication no. 158). Available from: [LINK]