- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) describes the premalignant dysplasia of the perineal and anal epithelium, driven by infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV). Over time, it may progress to anal cancer, requiring chemoradiation and potential surgery.1

Despite only accounting for <1% of all new cancers, anal cancer is a highly preventable cancer.

This article has been written for medical students to understand the pathophysiology, presentation, and treatments available for these conditions.

Epidemiology

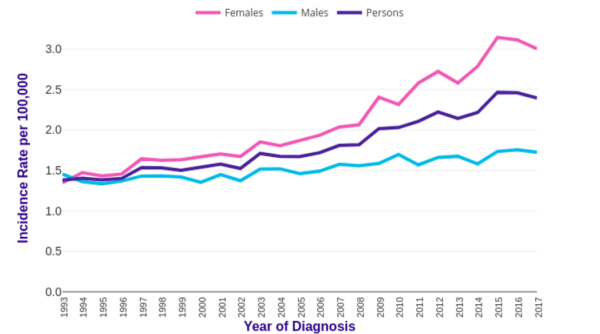

In the UK, anal cancer accounts for less than 1% of all new cancer cases. Its incidence has steadily been increasing from 1.4 in 1993 to 2.4 per 100,000 in 2017, meaning around 1,519 new cases per year (Figure 1).2

The majority (66%) of anal cancer cases are among women, and the incidence is strongly related to older age, with a peak incidence for both men and women at 65-69.2

Important high-risk groups include people living with HIV (PLWH) and reporting receptive anal intercourse, where prevalence can be as high as 87% in men and 68% in women.1

Although not an AIDS-defining malignancy, the incidence of anal cancer in people living with HIV is 20-40 times higher and occurs at a younger age.3

Aetiology

The development of anal cancer is highly linked to infection with HPV. This non-enveloped double-stranded DNA virus belongs to the Papillomaviridae family that infects the squamous epithelia of the anogenital tract.

HPV is primarily transmitted through sexual intercourse and usually causes a transient infection that is cleared by the immune system with no clinical symptoms within two years.4

However, certain oncogenic strains of the virus (particularly 6, 11, 16, 18 and 33) encode tumour suppressor proteins E5, E6 and E7 which interfere with the tumour suppressors p53 and retinoblastoma protein, resulting in cellular dysplasia.

Dysplasia of anal cells is called anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) and has the potential to transform into anal cancer, similarly to how HPV-driven cervical epithelial neoplasia (CIN) can lead to cervical cancer.4

Anatomy and pathogenesis

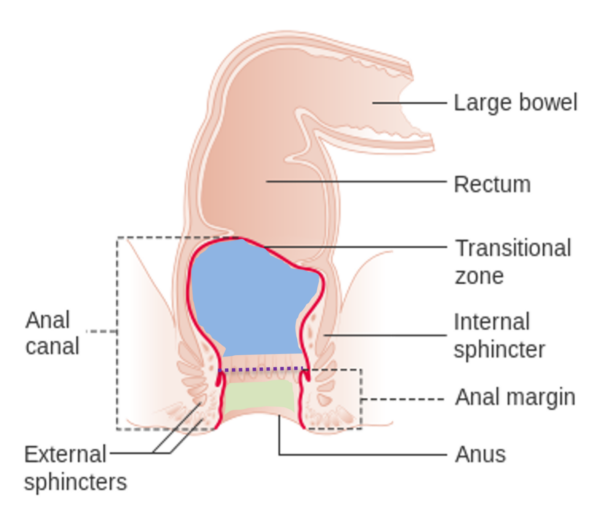

Anal cancers are sub-divided into anal canal and anal margin tumours (within 5cm of the anal orifice).3

The anal canal (Figure 2) is the terminal segment of the large intestine, bordered by the anorectal junction (transitional zone) and the anal margin. The anal canal is 2-3 inches long and can be divided into the upper zone (blue) and the lower zone (green), separated by the pectinate line, otherwise known as the dentate line (purple dashed line).3

Immediately above the pectinate line marks the transitional epithelium, where the simple columnar epithelium of the proximal rectum transitions to the squamous cells lining the anal canal.

Around 90% of anal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas arising at this squamocolumnar junction.3 Adenocarcinomas arise from the glandular cells under the anal mucosa.2

The anal verge refers to the distal end of the canal wherein the squamous cells of the anal canal transition to the epithelium of the perianal margin, where there is pigmented skin surrounding the anal orifice. This can be the site of melanomas.2

Once established, anal cancer primarily spreads directly into soft tissues and through the lymphatic system. The most common pattern of spread depends upon the location of cancer; anal margin tumours spread to the inguinal lymph nodes and more proximal cancers spread to the pelvic lymph nodes.5

Risk factors

Considering the close association between the development of AIN and anal cancer with HPV infection, behaviours that may predispose to HPV infection are implicated in the development of AIN and anal cancer. These risk factors include:3

- Receptive anal intercourse

- Men-who-have-sex-with-men

- Multiple sexual partners

- High-risk sexual behaviours

Furthermore, clinical factors that impair the immune system’s ability to eliminate HPV are implicated, these include:3

- Living with HIV

- Medical immunosuppression (e.g. renal transplant recipient)

- Women with a history of cervical cancer or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- Smoking

Importantly, there is an estimated 72-90% of people living with HIV who are co-infected with HPV, and anal cancer risk is 28-29 times higher in this group compared to the general population, as the immunodeficiency caused by HIV prevents the immune clearance of oncogenic HPV proteins.1

For this reason, the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland (ACPGBI) suggests routine HIV testing in patients with anal cancer, especially those from high-risk groups such as MSM.3

Clinical features

History

AIN is often asymptomatic and around 20% of people with anal cancer have no symptoms.

However, the most common symptom is anal pain and bleeding. Other symptoms may include:3

- Anal itching/discomfort

- Palpable mass

- Skin change: roughening, thickening

- Skin lesions: lumps, ulcers

- Faecal incontinence

- Tenesmus

- Palpable inguinal nodes

Unfortunately, patients commonly delay consulting a physician and their symptoms may be attributed to more common presentations (Table 1).3

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- HPV infection & vaccination history

- HIV infection & testing history

- Sexual risk: MSM, high-risk sexual encounters, multiple sexual partners

- Immunosuppression

- History of anal trauma

- Haemorrhoids

- Family history of colorectal cancer (to rule out an alternative cause of rectal bleeding)

Clinical examination

Although not diagnostic, a visual examination, inguinal lymph node palpation and digital rectal examination should be performed to detect irregularities of the mucosa (including size and location), the degree of anal canal circumference involvement and the impact on sphincter tone and bowel function.3

Considering the strong association with HPV and the anatomical closeness of the anus and vagina, any suspicion of anal cancer or AIN in female patients necessitates a vaginal examination to exclude vaginal invasion and cervical examination and smear to rule out any HPV infection and HPV-driven cervical changes.3

Differential diagnoses

Table 1. Differential diagnoses to consider in the context of anal cancer.

| Differential diagnosis | Clinical summary |

|

Haemorrhoid |

|

|

Rectal cancer |

|

|

Anal fissure |

|

|

Anal fistula |

|

|

Genital wart |

|

|

Pruritus ani |

|

Investigations

Diagnosis of both AIN and anal cancer requires examination under anaesthetic (EUA) of the anal canal and formal biopsy with anoscopy to visualise any masses or abnormalities and take appropriate excisional biopsies for histological analysis and grading.3

In addition to histology, anal cancers should be routinely staged by clinical assessment, pelvic MRI and CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. Where available, the use of PET scanning can improve lymph node and metastatic staging.3

Importantly, cervical screening should be performed in female patients due to the strong association with HPV.3

In addition, HIV testing should be considered in patients presenting with AIN or anal cancer, particularly among those deemed high risk for HIV acquisition. This is important to prevent onward HIV transmission and to inform downstream chemoradiotherapy. 3

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Stool sample: MC&S for infection, faecal calprotectin

- Rectal swab: HPV

- Cervical swab: HPV

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: anaemia (due to bleeding), raised white cell count (infection)

- CRP: infection

- U&E: baseline and assess for organ dysfunction in metastatic disease

- HIV serology: co-infection with HIV

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:

- Endoscopic ultrasound: identification of tumour and lymph node size

- Chest X-ray: exclude lung metastases (rare)

- CT chest, abdomen and pelvis: visualisation of primary lesion and metastases

- MRI pelvis: locoregional staging

- 18F-FDG PET/CT: detection of lymph node involvement and distant metastases

Other investigations

An ultrasound-guided inguinal lymph node biopsy is used to identify cancerous cells.

Diagnosis

Staging and grading

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) staging

The dysplastic changes in the abnormal cells reflect the staging used for the comparable cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and are related to the thickness of the skin with abnormal changes.3

- AIN 1: abnormal cells in the lower one-third of the thickness of the skin covering the anus.

- AIN 2: abnormal cells in the lower two-thirds of the thickness of skin covering the anus.

- AIN 3: abnormal cells in the full thickness of the skin of the anus.

The terminology used to describe AIN is not fully agreed upon, so AIN staging may also be referred to as:1

- Low-grade (AIN1+AIN2): nuclear enlargement, nuclear membrane irregularity with a preserved nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio

- High-grade (AIN3): loss of maturation, nuclear hyperchromasia, membrane irregularity, decreased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio

Anal cancer grading

Anal cancer is graded using the TNM staging system as recommended by the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the International Union Against Cancer.7

Management

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN)

The management of AIN aims to prevent progression to more severe staging and anal cancer and is dependent on its severity and staging.

Low-grade AIN (AIN1 + AIN2) may not require treatment as the abnormal cells may resolve without treatment, whereas high-grade AIN (AIN 3) does require treatment.1

Treatment of AIN may include:1

- Topical treatment: trichloroacetic acid, 5-fluorouracil and immunomodulator creams such as imiquimod

- Ablative therapies: including infrared coagulation, electrocautery, carbon dioxide laser and photodynamic therapy

- Surgical excision

Follow up

AIN surveillance aims to identify progression to more severe staging and early invasive carcinoma. This should include a rectal examination, anoscopy and, where necessary, a biopsy every 6 months for a minimum of 5 years.1

Anal cancer

Specialist multi-disciplinary teams (MDT) lead the treatment of anal cancers to achieve the best outcomes for morbidity and mortality. This requires input from colorectal surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, clinical nurse specialists and data managers. Input should also be sought from gynaecological oncologists for female patients.3

Wide local excision alone may be adequate for small tumours at the anal margin however, the standard care of anal cancer is chemoradiation (CRT). This involves radiotherapy alongside dual-agent chemotherapy, commonly mitomycin and fluorouracil.

In people living with HIV, CD4 cell counts, and symptoms of other HIV-related diseases must guide attenuation of chemoradiotherapy.3

Pre-treatment defunctioning stoma formation is appropriate for patients with definitive indications such as bowel obstruction, fistulation and peri-anal sepsis. This may also be appropriate to improve CRT completion in patients with vaginal invasion, severe tenesmus or severe defecation pain. Due to the destruction of the normal sphincter anatomy, anal fibrosis and stenosis, the reversal rate for these stomas is low.3

For those who fail to achieve a satisfactory local response to CRT, an abdominoperineal resection is required, resulting in a permanent colostomy. These patients may also require inguinal lymph node dissection.3

Follow up

Anal cancer surveillance aims to detect local disease failure amenable to salvage surgery, detect distant metastases and manage late consequences of treatment.

As regression of anal cancers may be slow and most likely to occur within the first three years, patients should undergo perineal inspection, digital anorectal examination and anoscopy to assess tumour size every 6 weeks until a complete response is achieved. Biopsies should be performed if the tumour has stopped responding or has increased in size.3

As part of routine follow-up, female patients should have a careful gynaecological examination. It is common to detect class II cervical smear following pelvic radiation, however, biopsy should still be performed to exclude new cervical cancer. These patients should also continue to have their regular cervical smear tests.3

Prevention

In the UK, girls and boys aged 12-13 are currently offered a quadrivalent HPV vaccine to protect against HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18. This will shortly be improved to a 9-valent vaccine to further protect against GPV 33, 45, 52 and 58.7

The benefits of the vaccine in reducing the incidence of cervical cancer have been well-documented, and studies suggest a role for its prevention of anal cancer too.8,9

Although some studies have shown the vaccine may prevent recurrence of AIN after targeted destruction, trials have shown that is unlikely to be an effective treatment of high-grade AIN on its own.1

Screening

Studies have suggested screening in high-risk populations such as HIV-positive, MSM and those with a history of cervical cancer could be cost-effective and reduce the progression of AIN to anal cancer.3

Despite this, and the clear benefits of screening for similar CIN and cervical cancer, there are currently no official screening guidelines for AIN. 7

Complications

Complications may occur from all treatment approaches:3

- Topical chemotherapies may induce hypopigmentation and skin irritation

- Surgical excision(s) increase the risk of stenosis, impaired sphincter function and faecal incontinence

- Chemoradiation-related pelvic toxicity may cause leukopenia, thrombocytopaenia, proctitis, cystitis and acute dermatitis and radiation-induced menopause

Both male and female patients should be counselled regarding chemotherapy-induced infertility due to azoospermia and radiation-induced menopause, respectively. 3

Prognosis

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN)

The rate of conversion from low-grade to high-grade AIN and progression to anal cancer is controversial owing to a lack of agreeing evidence.

Progression rates from high-grade AIN to anal cancer have been shown to vary 0.2% in HIV-positive MSM and 0.02% in HIV-negative MSM within one year of treatment, up to 9-13% of patients within 5 years if left untreated.10

A retrospective study also showed regression of high-grade AIN to low-grade in 17% of patients and regression to no disease in 7%.11

Anal cancer

For patients treated for anal cancer, up to 10% will have persistent local disease following treatment with CRT. This is usually palpable on digital rectal examination before the onset of symptoms and within 2 years of CRT completion. 3

As with most cancers, a positive prognostic outlook is heavily influenced by an early stage of disease at diagnosis.3,2

However, overall, anal cancer mortality is relatively low, with only 334 deaths in 2018.2

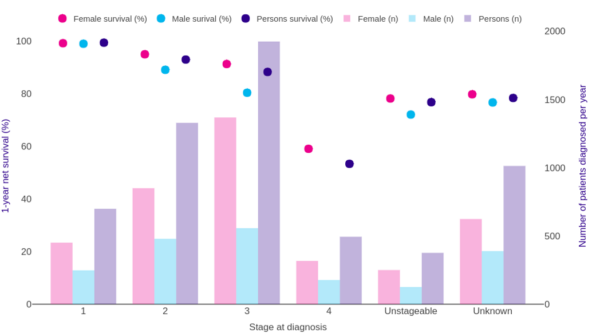

Survival rates of anal cancer are generally favourable, with an average of 83.7% 1-year survival and 57.1% 5-year survival.2

Survival rates are more favourable in younger patients, with a 5-year survival of 76% in 15-49 year-olds compared to 49.5% in 70-89 year-olds. Female patients have greater survival rates than males at all ages (Figure 4).

Key points

- Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) is a premalignant lesion for anal cancer caused by HPV infection

- Anal cancers are rare, and the most common is squamous cell carcinoma of the squamocolumnar junction

- The incidence is increasing, especially among HIV-positive men-who-have-sex-with-men

- Risk factors include HPV infection, HIV infection, men-who-have-sex-with-men and immunosuppression

- Common symptoms include anal pain, rectal bleeding, palpable masses and skin changes

- DRE, anoscopy and biopsy are required for the diagnosis of AIN and anal cancer

- AIN is staged as 1, 2 or 3 according to the depth of cells affected

- Pelvic MRI, CT abdomen and pelvis and PET scans are used to facilitate TNM staging of anal cancer

- AIN is managed through watchful waiting, topical immunomodulation, ablation or surgical excision

- Anal cancer is treated by chemoradiation but may require surgical excision and abdominoperineal resection

- Progression rates of AIN are unknown but generally low and higher in people living with HIV

- Prognosis of anal cancer is generally favourable but worsens with a higher T stage at diagnosis

Reviewer

Mr Pradeep Thomas

Consultant General Surgeon

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Siddharthan, R.V., Lanciault, C. and Tsikitis, V.L., 2019. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia: diagnosis, screening, and treatment. Annals of gastroenterology, 32(3), p.257.

- Cancer Research UK. Anal cancer statistics. Available from: [LINK]

- Geh, I., Gollins, S., Renehan, A., Scholefield, J., Goh, V., Prezzi, D., Moran, B., Bower, M., Alfa‐Wali, M. and Adams, R., 2017. Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland (ACPGBI): Guidelines for the Management of Cancer of the Colon, Rectum and Anus (2017)–Anal Cancer. Colorectal Disease, 19, pp.82-97.

- Krzowska-Firych, J., Lucas, G., Lucas, C., Lucas, N. and Pietrzyk, Ł., 2019. An overview of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) as an etiological factor of the anal cancer. Journal of infection and public health, 12(1), pp.1-6.

- BMJ Best Practice. Anal Cancer- Aetiology. Available from: [LINK]

- K.-H. Günther, Klinikum Main Spessart, Lohr am. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Anal Rim. License: [CC BY]

- Brierley J, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind C, eds. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th edn. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2017.

- Public Health England 2021. Correspondence: HPV immunisation programme: introduction of Gardasil® 9. Available from: [LINK]

- Stier, E.A., Chigurupati, N.L. and Fung, L., 2016. Prophylactic HPV vaccination and anal cancer. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 12(6), pp.1348-1351.

- Machalek, D.A., Poynten, M., Jin, F., Fairley, C.K., Farnsworth, A., Garland, S.M., Hillman, R.J., Petoumenos, K., Roberts, J., Tabrizi, S.N. and Templeton, D.J., 2012. Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet oncology, 13(5), pp.487-500.

- Tong, W.W., Jin, F., McHugh, L.C., Maher, T., Sinclair, B., Grulich, A.E., Hillman, R.J. and Carr, A., 2013. Progression to and spontaneous regression of high-grade anal squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-infected and uninfected men. Aids, 27(14), pp.2233-2243.

- Cancer Research UK. Anal cancer survival by stage at diagnosis. Available from: [LINK]