- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Barrett’s oesophagus is a condition where there is an abnormal change in the cells lining the lower portion of the oesophagus due to chronic damage from gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

It has a prevalence of 2.3% among patients with symptoms of reflux.

Barrett’s oesophagus is a pre-malignant condition where patients have an increased risk of developing oesophageal adenocarcinoma.1,2,3

Aetiology

Anatomy

The oesophagus is a fibromuscular tube which carries food from the pharynx to the stomach. It originates at the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage at the level of C6.

The oesophagus descends through the superior mediastinum of the thorax between the trachea and the vertebral bodies of T1 and T4. It then enters the abdomen via the oesophageal hiatus at T10.

The abdominal portion of the oesophagus is approximately 1.25cm long. It terminates at the cardiac orifice of the stomach at the level of T11.4

Food is transported through the oesophagus by peristalsis (rhythmic contractions of the muscles).4

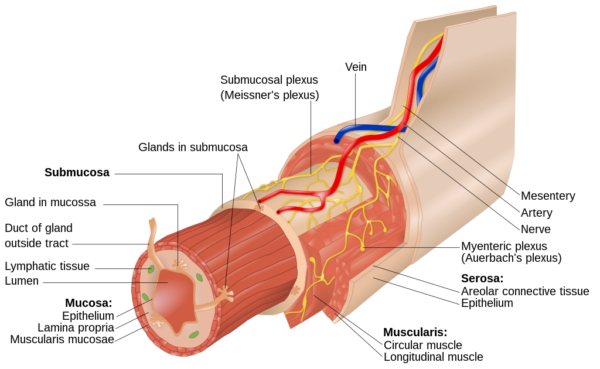

The oesophagus has three layers (Figure 1).

- Adventitia: an outer layer of connective tissue

- Muscle layer: an external layer of longitudinal muscle and an inner layer of circular muscle

- Mucosa: non-keratinised stratified squamous epithelium (continuous with the columnar epithelium of the stomach)

Oesophageal sphincters prevent the entry of air and the reflux of gastric contents:

- Upper oesophageal sphincter: striated muscle sphincter at the junction between the pharynx and oesophagus. Produced by the cricopharyngeus muscle. Usually, it is constricted to prevent the entry of air into the oesophagus.

- Lower oesophageal sphincter: located at the gastro-oesophageal junction, to the left of the T11 vertebra. At rest, the sphincter prevents reflux of acidic gastric contents into the oesophagus.

During peristalsis, the sphincters relax to allow food to enter the stomach.4

Pathophysiology

Barrett’s oesophagus is a consequence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). GORD is caused by weakness in the lower oesophageal sphincter, which allows reflux of gastric contents back up the oesophagus, causing damage to the mucosa.

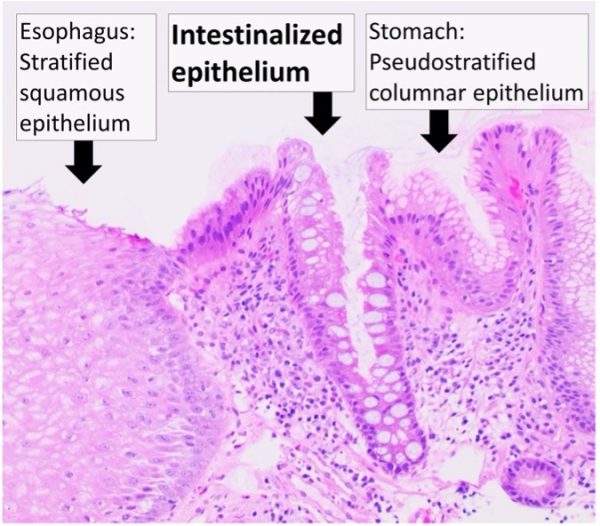

Irritation of the lower oesophagus for a prolonged period causes a transformation (metaplasia) from squamous epithelium to columnar type intestinal epithelium (Figure 2).

Occasionally, dysplasia occurs, which predisposes to malignant transformation.1,4

Malignant transformation occurs along a metaplasia-dysplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence

Risk factors

Risk factors for Barrett’s oesophagus include:2

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)

- Acid-bile reflux

- Increasing age

- Obesity

- White ethnicity

- Male sex

Recent evidence also indicates a genetic predisposition.6

Clinical features

The change from normal to premalignant cells in Barrett’s oesophagus is asymptomatic. However, patients may have symptoms of acid reflux.

Typical symptoms of acid reflux include:1

- Heartburn

- Regurgitation

- Trouble swallowing (dysphagia)

- Vomiting blood (haematemesis)

- Unintentional weight loss because eating is painful (odynophagia)

- Less commonly: chest pain, laryngitis, cough, dyspnoea, wheezing

For more information, see the Geeky Medics OSCE guide to gastrointestinal history taking.

Investigations

The main investigation for Barrett’s oesophagus is an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy.

At endoscopy, Barrett’s oesophagus is characterised by the replacement of the paler squamous epithelium with ‘salmon-coloured’ columnar epithelium above the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ).

The length (in centimetres) of changes to the epithelium is measured and helps inform subsequent management and surveillance.

The minimum length of epithelial changes required for a diagnosis is 1cm above the GOJ.

The Prague C & M classification

The Prague C & M classification is used to determine disease severity:

- C: circumferential extent of disease. The distance from the GOJ to the highest location metaplasia is present around the entire circumference of the oesophagus

- M: distance from the GOJ to the highest location of metaplasia

- Example: C3 M5

The higher the numbers, the more severe the disease and the greater the risk of malignant transformation.9

Management

Patients with Barrett’s oesophagus are offered long-term high-dose proton pump inhibitors to help manage symptoms.

They are also offered endoscopic surveillance after the initial diagnosis to monitor for signs of dysplasia (Table 1).9,10

Table 1. The management of Barrett’s oesophagus.

| Initial endoscopy findings | Management |

|

No dysplasia |

High-definition white light upper GI endoscopy (oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy/OGD) and biopsies taken every 2cm on initial detection.

|

|

Low-grade dysplasia |

If confirmed on follow-up endoscopy, radiofrequency ablation is recommended. |

|

High-grade dysplasia |

MDT discussion and repeat endoscopy at a specialist centre. Options include are:

|

Complications

Compared to the general population, patients with Barrett’s oesophagus have a 30x increased lifetime risk of developing oesophageal adenocarcinoma.11

However, the absolute risk of Barrett’s oesophagus progressing over time and developing into oesophageal adenocarcinoma is fairly low (annual incidence of 0.33%).12

Barrett’s oesophagus has been associated with an increased risk of oesophageal strictures. This occurs due to acid reflux and is treated with endoscopic dilation.

Key points

- Barrett’s oesophagus is a premalignant condition of the oesophagus which increases a patient’s chances of developing oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

- In Barrett’s oesophagus, the mucosal layer of the oesophagus undergoes metaplasia into columnar type intestinal epithelium. Then occasionally, dysplasia may occur, eventually progressing to oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

- The most common cause is gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

- It commonly presents with symptoms of acid reflux such as regurgitation, heartburn and trouble swallowing.

- Barrett’s oesophagus is diagnosed via upper GI endoscopy and biopsy with the minimum length of epithelial changes required for a diagnosis being 1cm above the GOJ.

- Patients must undergo surveillance via endoscopy and biopsy to monitor for signs of progression to oesophageal adenocarcinoma. The frequency of monitoring depends on the degree of dysplasia present. If dysplasia is identified, patients can undergo radiofrequency ablation.

- Patients with Barrett’s oesophagus have a 30x increased risk of developing oesophageal adenocarcinoma compared to the general population.

Reviewer

Dr Leo Alexandre

Consultant Academic Gastroenterologist

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- BMJ Best Practice. (n.d.). Barrett’s Oesophagus. [online] Available from: [LINK]

- Spechler, S.J. and Souza, R.F. (2014). Barrett’s Esophagus. The New England Journal of Medicine, 371, pp.836–845.

- Pophali, P. and Halland, M. (2016). Barrett’s oesophagus: diagnosis and management. BMJ, p.i2373.

- OpenStax. The Mouth, Pharynx, and Esophagus. Available from: [LINK]

- Goran tek-en. Image showing layers of oesophagus. License: [CC BY-SA 4.0]

- P, Fitzgerald RC; Genome-wide association studies in oesophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s oesophagus: a large-scale meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016 Oct;17(10):1363-1373.

- Mikael Häggström, M.D. Microscopic image showing histology of Barrett’s Oesophagus. License: [CC0 1.0]

- Samir. Endoscopic image of changes seen in Barrett’s Oesophagus. License: [Public domain]

- Fitzgerald, R.C., di Pietro, M. and Ragunath, K. (2013). British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s Oesophagus. Gut, pp.1–36. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE, Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s oesophagus with low-grade dysplasia or no dysplasia. Available from: [LINK]

- Solaymani-Dodaran, M. (2004). Risk of oesophageal cancer in Barrett’s oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut, 53(8), pp.1070–1074.

- Desai, T.K., Krishnan, K., Samala, N., Singh, J., Cluley, J., Perla, S. and Howden, C.W. (2011). The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in non-dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a meta-analysis. Gut, 61(7), pp.970–976.