- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

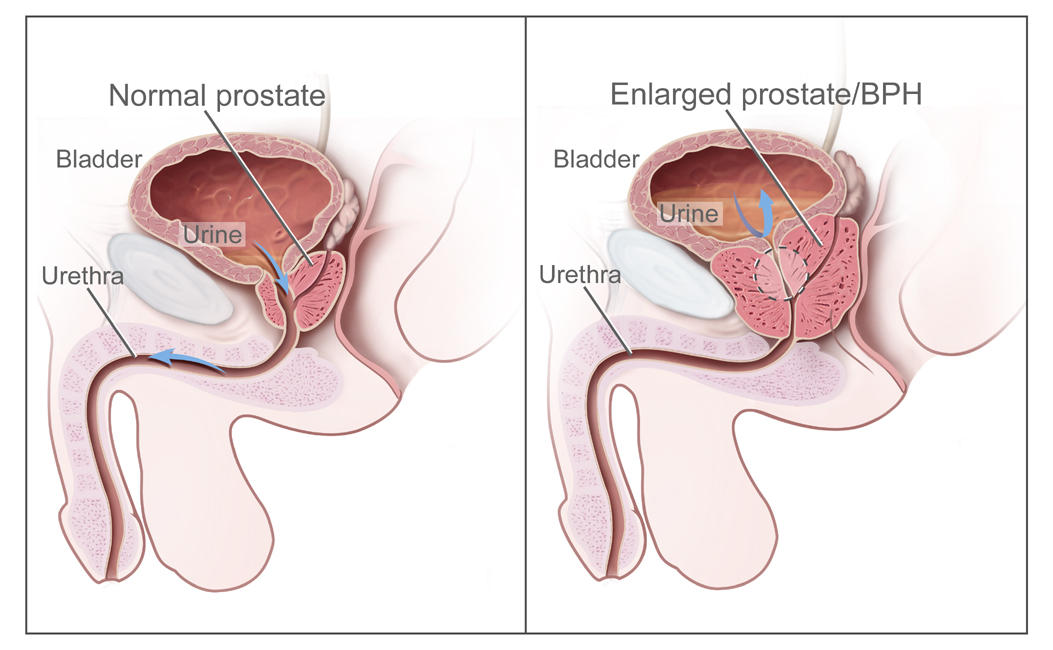

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or benign prostatic enlargement refers to the benign enlargement of the prostate gland and is a common condition in men as they age.

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) and BPH are interchangeable terms which can lead to lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) by causing compression or narrowing of the prostatic urethra, limiting the outflow of urine.

The prevalence of BPH increases after the age of 40, with a prevalence of 8% – 60% in those aged 90.1

As the name suggests, BPH is a benign condition associated with the proliferation of the smooth muscles and the epithelial cells in the transition zone of the prostate; there is no potential for malignancy. Often men can have prostatic enlargement, associated bladder outlet obstruction, and be asymptomatic.2

Aetiology

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is multifactorial in pathophysiology, including genetic, lifestyle, and hormonal factors.3

The most commonly accepted theory is that the hormones testosterone and dihydrotestosterone are the most significant contributors to the condition. As a result, pharmacological therapy has been developed to target these hormones. 5-alpha reductase inhibitors prevent the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (the hormone stimulating prostatic enlargement).

Anatomy

Prostate tissue is composed of a glandular component and a stromal component. The glandular component consists of secretory ducts and acini, while the stromal component consists of collagen and smooth muscle.

The proliferation of cells in BPH results in increased prostate volume and stromal smooth muscle tone. This enlargement occurs primarily in the peri-urethral transition zone of the prostate. Increased bulk in this area due to hyperplasia or hypertrophy leads to urethral compression and obstruction of urine outflow.

Risk factors

Non-modifiable risk factors include the patient’s age, genetics, and geography.

Modifiable risk factors include hormones (testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, oestrogen), metabolic syndrome, diabetes, diet, physical activity, and inflammation.

Clinical features

History

BPH can be asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally on a rectal examination performed to investigate another condition (e.g. haemorrhoids, faecal incontinence, suspected anal or rectal cancer).

Typical symptoms of BPH include:

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), such as a poor urinary stream

- Acute urinary retention (painful)

- Chronic urinary retention (painless low-pressure retention)

- Renal impairment with bilateral hydronephrosis and chronic retention (painless high-pressure)

- Haematuria

- Recurrent urinary tract infection

- Bladder stones

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Caffeine intake: coffee, tea, energy drinks etc.

- Sexual history: to exclude prostatitis

- Red flag symptoms for malignancy: fever, weight loss, enlarged lymph nodes, loss of appetite

- Recent urinary catheterisation

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)

Lower urinary tract symptoms can be divided into the following.

Voiding symptoms:

- Weak or intermittent stream

- Straining

- Hesitancy

- Terminal dribbling

- Incomplete emptying

Storage symptoms:

- Frequency

- Urgency

- Incontinence

- Nocturia

Post-micturition symptoms:

- Post-micturition dribbling

Clinical examination

In the context of suspected BPH, an abdominal examination is required with palpation and percussion of the supra-pubic area to evaluate for residual urine. A bladder is only palpable when it contains 200ml or more of urine.

Additionally, the external genitalia should be examined, alongside performing a thorough rectal examination (PR).

Typical clinical findings of BPH on rectal examination are an enlarged and non-tender prostate with a rubbery consistency. The median furrow is lost in enlarged prostate glands. The normal prostate gland size is 20 ml or 20 grams, and only 4% of prostates grow larger than 100ml.

The prostate should also be evaluated for nodules, which may suggest malignancy.

Differential diagnoses

Red-flag conditions to consider in the differential diagnoses for BPH include bladder/prostate cancer and chronic high-pressure retention.5

When considering bladder/prostatic malignancy as possible differentials for patients with BOO, red-flag symptoms need to be explored. The most common presentation is painless gross haematuria with or without clots that may be intermittent or constant. Patients may also complain of lower back pain. Palpable lumps or lymphadenopathy and “B symptoms” (fever, night sweats, weight loss, loss of appetite) may also indicate malignancy.

Other differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Urinary tract infection

- Sexually transmitted infections

- Prostatitis

- Neurogenic bladder

- Urinary tract stones

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- International prostate symptom score (IPSS): measures the severity of LUTS

- Uroflowmetry (flow rate & US bladder PVR): measures the volume of urine passed, the speed at which it is passed, and how long it takes to be passed

- Bladder diary (3-day): objectively assesses patient symptoms by monitoring fluid intake, frequency of urine passage, and urine leakage

- Urodynamics: assesses bladder and urethral function at storing and releasing urine by measuring pressures. This is indicated in very young or old patients or when the diagnosis is unclear.

- Urinalysis: for evidence of a urinary tract infection (however, this can also be abnormal in other prostatic conditions such as prostatitis)

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: to assess haemoglobin for anaemia, possibly indicating bleeding and/or malignancy. An elevation in white cell count and CRP would indicate an infectious aetiology.

- Urea & electrolytes: for assessment of renal function. If these are abnormal, an ultrasound of the kidneys is required.

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA): elevated PSA may suggest prostate cancer (or prostatitis), although PSA is not specific for malignancy and can be elevated in several conditions (including BPH).

Diagnosis

The gold-standard investigation for diagnosing BPH is a rectal examination followed by uroflowmetry and post-void bladder scanning in conjunction with an IPSS questionnaire.

Management

Conservative

Conservative management of BPH includes lifestyle modifications (weight loss, evening fluid restriction, and reducing caffeine intake).

Medical

Medical management of BPH includes:

- Alpha antagonists (e.g. tamsulosin, doxazosin, terazosin)

- 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (e.g. finasteride)

Anticholinergics can be considered for associated storage symptoms. There is no evidence of an increase in acute urinary retention if no history of acute urinary retention exists.

Surgical

Surgical management of BPH includes:

- Transurethral resection of the prostate (bipolar or monopolar): most common surgical management

- Transurethral vaporisation of the prostate (Greenlight)

- Endoscopic enucleation of the prostate (bipolar, monopolar, holmium, thulium)

- Minimally invasive surgery such as Rezum or Urolift

- Open or robotic simple prostatectomy

Surgical management is reserved for patients with symptoms impacting their quality of life, symptoms refractory to medical management, and those with complications that are absolute indications for surgery.

Absolute indications for surgical management include:

- Progression of symptoms despite maximal medical therapy

- Refractory urinary retention

- Recurrent urinary tract infections

- Recurrent haematuria

- Renal impairment

- Bladder stones

Complications

Common complications that may occur as a result of benign prostatic hyperplasia include:

- Acute urinary retention

- Chronic retention

- Urinary tract infection (due to incomplete emptying)

- Haematuria

- Bladder calculi

Key points

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia is the enlargement of the prostate gland, primarily affecting the smooth muscles and the epithelial cells in the transition zone.

- The aetiology of BPH is multifactorial and involves genetic, lifestyle, and hormonal factors.

- Though mostly asymptomatic, BPH commonly presents with lower urinary tract symptoms, decreased urine flow rate, impaired detrusor contractility and outflow obstruction.

- The most common clinical findings on rectal examination are an enlarged, smooth, and non-tender prostate.

- Management of BPH involves lifestyle modifications of restricting evening fluids and caffeine intake. Medical management may be considered with alpha antagonists and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.

- Surgical management involves transurethral resection of the prostate (most commonly) or transurethral vaporisation of the prostate. Several newer techniques are also available, including holmium laser enucleation of the prostate, minimally invasive surgery, open or robotic simple prostatectomy,

- Complications can include acute or chronic urinary retention, urinary tract infection, haematuria, and bladder calculi.

Reviewer

Mr Derek Hennessey

Consultant Urologist

Mercy University Hospital, Cork, Ireland

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Lim KB. Epidemiology of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK].

- National Cancer Institute. Understanding prostate changes: a health guide for men. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK].

- Lawrentschuk N, Ptasznik G, Ong S. Benign prostate disorders. Published in 2012. Available from: [LINK].

- National Cancer Institute. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. License: [Public domain]

- Ng M, Baradhi KM. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK].