- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Biliary atresia is a rare, congenital condition that affects the biliary tree. It is characterised by progressive inflammation and fibrosis of the extrahepatic ducts leading to cholestasis, liver damage and failure.

Biliary atresia usually presents in infants and young children and can be life-threatening if left untreated.

In the UK, the incidence is around 1 in 17,000 live births annually.1 Worldwide, it is considered the most common cause of liver transplantation in children.2

Aetiology

The underlying cause for biliary atresia remains mostly unknown, but it is believed to be multifactorial, involving genetic and acquired causes:2

- Genetics: a genetic predisposition is implicated as the condition seems more common in certain geographic areas. Some gene mutations have been found to increase the susceptibility to developing biliary atresia (e.g. CFC1, PKD1L1, ADD3, and EFEMP1).

- Viral infections: a correlation between perinatal infection with rotavirus and reovirus type 3 and biliary atresia has been shown in some studies in mice. These results are still debated and have yet to be confirmed in humans.

- Immune-mediated: the above infections (or others) could trigger an autoimmune-like reaction perinatally which causes cell death at the level of the bile duct.

- Defects in morphogenesis: biliary atresia has been linked to other congenital abnormalities. This could indicate that an insult occurs at a critical point during embryological development leading to the malformation of the extrahepatic biliary ducts.

Classification

Two classification models can be used for biliary atresia.2

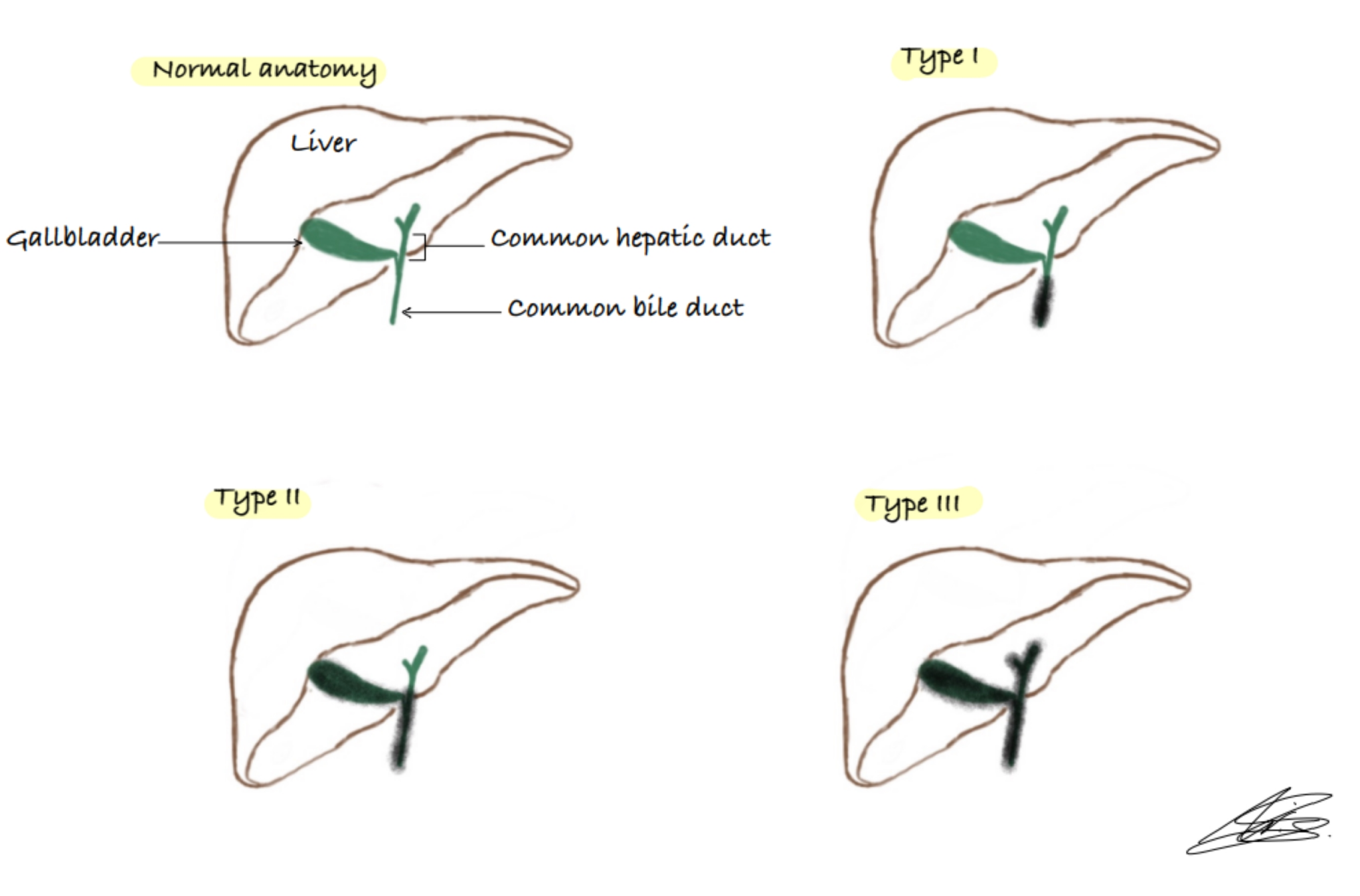

The Ohi system classifies biliary atresia according to the degree of anatomical damage:

- Type I (~10%): patent proximal ducts but atresia of the common bile duct

- Type II (~2%): atresia of the common bile duct and hepatic duct

- Type III (~88%): atresia of almost all extrahepatic ducts, including the porta hepatis

Biliary atresia can also be classified according to its presentation:

- Isolated biliary atresia (most common)

- Biliary atresia with other congenital anomalies: the most common of these is the biliary atresia splenic malformation syndrome, which is associated with polysplenia, situs inversus, cardiac malformations, and vascular anomalies.3,4

Clinical features

History

Symptoms of biliary atresia may not present until after the first week of life, at which point features of cholestasis develop.2

Typically, infants present with persistent neonatal jaundice (beyond 14 days). The jaundice is usually associated with pale stools and dark urine due to biliary obstruction. In addition, some infants may develop bruising due to vitamin K deficiency.

Clinical examination

The most common finding on clinical examination is jaundice.

In the later stages of the disease, usually seen in infants over three months old, clinical findings may include:5

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Ascites

- Failure to thrive: due to malabsorption of fats

Differential diagnoses

Other causes of obstructive jaundice that can occur in the neonatal period include:2,5,7

- Choledochal cyst

- Cholelithiasis

- Spontaneous perforation of the bile duct

- Allagile syndrome: a rare disorder where a baby is born with fewer bile ducts than normal

Other differentials to consider (not related to the gallbladder) include:5

- Cystic fibrosis

- Lipid storage disorders

- Idiopathic neonatal hepatitis

- Congenital infections

- Alpha-1-antitrypsin (A1AT) deficiency

Investigations

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:2,6,8

- Newborn blood spot screening: although this does not test for biliary atresia, it includes a test for cystic fibrosis (a differential to exclude)2

- Liver function tests (LFTs): will be abnormal with conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia and raised gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT)5

NICE recommends that all children with neonatal jaundice have their bilirubin levels tested within 6 hours.6

Physiological causes of jaundice can be differentiated from liver disease because physiological causes will cause unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, whereas liver disease will cause conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.8

Imaging

Ultrasound is recommended as the first-line imaging investigation.5

Key ultrasound features of biliary atresia include:9

- The triangular cord sign (Figure 2): an echogenic sign representing the fibrous remnant of the extrahepatic bile duct

- Hepatic artery changes, which will be mainly larger

- Gallbladder ghost triad: small/atretic gallbladder with a length less than 19 mm (Figure 3), irregular or lobular contour, lack of smooth echogenic mucosal lining with an indistinct wall

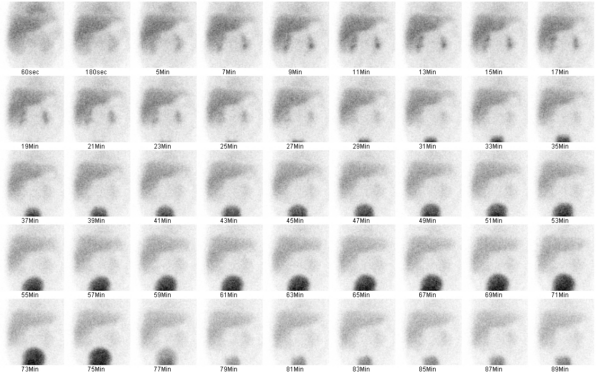

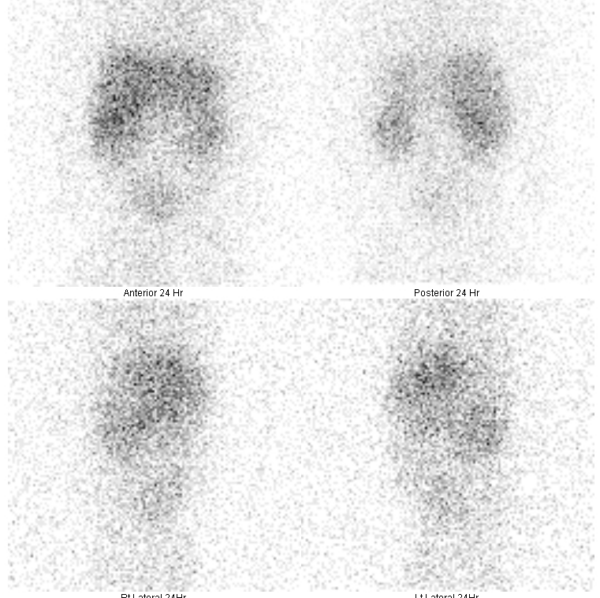

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy (technetium-99m) or hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid HIDA scan can also be performed. In biliary atresia, good hepatic uptake of the radioisotope will be seen (Figure 4), but there will be no evidence of biliary excretion into the bowels at the 24-hour follow-up (Figure 5).9

Other investigations

The preferred diagnostic investigation is a percutaneous liver biopsy.5 It would typically show bile duct proliferation with bile plugs.2

Operative cholangiography remains the gold standard investigation. However, it is only used if there is diagnostic uncertainty before treatment.3

Management

Patients with biliary atresia require early surgical treatment.6 Ideally, surgery should be performed by 45 days of life as this provides the best success rate and helps avoid liver transplantation.2,5

Surgical management

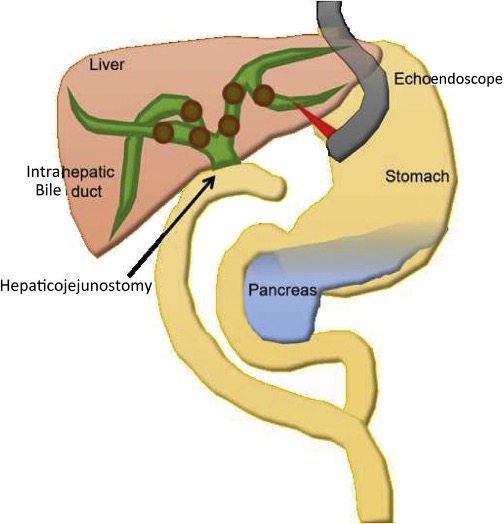

The surgical intervention of choice is the Kasai portoenterostomy.5

This procedure involves removing the damaged bile ducts and replacing them with a loop of intestine to allow bile to flow from the liver to the intestine.

The porta hepatis is anastomosed (in a Roux-en-Y fashion) to a part of the jejunum at the level of the hepatic hilum (Figure 5).5 The jejunum is then attached on the other end to the rest of the small intestine forming the Y-shaped connection.

It is important to note this procedure is not curative, and the disease can continue to progress in patients who have had bile flow restored.3

Liver transplantation

If portoenterostomy fails, liver transplantation may be required.5 Sometimes, a liver transplant may be required even after a successful Kasai procedure due to the progression of liver damage.2 Liver transplantation is avoided where possible to allow the child to continue their growth and is only considered in cases of end-stage liver failure.2

The indications for liver transplant are:10

- Failure of the Kasai procedure and reappearance of symptoms

- Growth retardation that is non-responsive to intensive nutritional support

- Development of portal hypertension and its complications (variceal bleeding, ascites)

- Progressive liver dysfunction marked by pruritus and coagulopathy

All patients will require antibiotic prophylaxis for the first year of life to prevent the development of cholangitis.2

Complications

The most common complications related to surgical intervention are:5

- Ascending cholangitis: would present with a recurrence of the initial symptoms (e.g. jaundice and pale stools)

- Obstruction of the Roux-en-Y loop: causing recurrent or delayed ascending cholangitis

- Cirrhosis: can eventually lead to hepatocellular carcinoma

- Portal hypertension

Key points

- Biliary atresia is a rare and potentially life-threatening condition characterised by fibrosis of the extrahepatic bile ducts.

- The cause of the condition is not fully understood, but it is most probably a multifactorial aetiology, including genetics and environmental factors

- The typical clinical presentation is jaundice with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Ultrasound and HIDA scans are used to confirm the diagnosis.

- The Kasai procedure is the standard treatment for biliary atresia, and early surgical intervention is key to preventing liver damage and failure.

- Some patients may have to undergo a liver transplant if surgery is unsuccessful.

- Ascending cholangitis and portal hypertension are the most common complications.

Reviewer

Dr Eleftheria Konstantoulaki | MRCPCH

Consultant Paediatrician

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Children’s Liver Disease Foundation. British Paediatric Surveillance Unit Survey on Biliary Atresia. 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Biliary Atresia. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Li-Zsa Tan. Biliary atresia, Don’t Forget the Bubbles, 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Siddiqui AI, Ahmad T. Biliary Atresia. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK. Biliary Atresia. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Jaundice in the newborn. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Definition & Facts for Alagille Syndrome. 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Kelly DA, Davenport M. Current management of biliary atresia. 2007. Available from: [LINK]

- Singh G, Yap J, Fortin F, et al. Biliary atresia. Radiopaedia.org. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Biliary Atresia. 2023. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Figure 2 and 3. Anjum Bandarkar. Biliary atresia – triangular cord sign. License: [CC BY-NC-SA]

- Figure 4 and 5. James Harvey. Biliary atresia. License: [CC BY-NC-SA]

- Figure 6. Sato et al. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy through a fistula of EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy: a new approach for right intrahepatic stones. License: [CC BY-NC-ND]