- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Burn injuries occur when the skin is damaged by heat sources, electricity, or chemical agents. It takes just 10 seconds of skin exposure to 60°C (140°F) heat for a full-thickness burn to occur.1

Around 130,000 people attend hospital each year with a burn, making burn injuries the fourth most common injury in the UK after road traffic collisions, falls and interpersonal violence.2,3 Approximately eight per cent of these patients require inpatient treatment.2

Burns can be life-threatening injuries that require prompt referral and treatment to prevent significant complications and permanent disability.

This article will provide an overview of how to initially assess a patient with burns using an ABCDE assessment and estimate the depth and percentage of the total body surface area burnt (%TBSA). It will also outline the initial management and surgical management, as well as the common local and systemic complications associated with burns.

Risk factors

Risk factors which increase the likelihood of a person suffering a burn include:4

- Young children: these injuries are often caused by spilling scalding drinks or from touching oven hobs or irons.

- Elderly people

- Occupation with increased exposure to fire

- Underlying medical conditions: epilepsy, peripheral neuropathy, cerebral palsy, or cognitive disabilities

- Alcohol use

- Drug use

- Smoking

- Poverty and overcrowding

Initial ABCDE assessment

Patients with burn injuries should undergo a systematic ABCDE assessment. Problems are addressed as they are identified, and the patient is re-assessed regularly to monitor their response to treatment.

There are areas within the ABCDE assessment that should be focused on in burn patients, and these are detailed below.

This guide has been created to assist students in preparing for emergency simulation sessions as part of their training, it is not intended to be relied upon for patient care.

Airway and C-spine

Evaluate the airway and look for signs of an inhalation injury.

An inhalation injury may occur after inhaling hot air, smoke or toxic fumes and can cause swelling of the airway leading to airway obstruction. There may also be another cause of airway obstruction that is not directly related to the burn (e.g. from facial trauma, a foreign body or vomit in the mouth).3

Factors that may increase the likelihood or are suggestive of an inhalation injury include:3

- A history of burns in an enclosed space

- Burns to the face or oropharynx

- Singed nasal or facial hairs

- A hoarse voice

- Respiratory distress/stridor

If an inhalation injury is recognised or likely given the history, the patient should be sat upright and receive an urgent senior anaesthetic review. Early intubation with an uncut endotracheal tube may be indicated to protect the patient’s airway.5

A C-spine injury should also be excluded. If in doubt, immobilise the cervical spine.

Breathing

Compromised gas exchange may occur secondary to:2

- Carbon monoxide poisoning

- Direct damage from an inhalation injury to the lower airways

- Burnt tissue on the chest or neck creating a constrictive eschar and reducing chest expansion

- Other traumatic chest injuries (e.g. tension pneumothorax, haemothorax, flail chest)

Eschar

Eschar is a collection of tight and leathery dead tissue caused by deep partial or full-thickness burns.

When a constrictive eschar forms around the circumference of a limb it may constrict distal circulation causing limb ischaemia. If eschar forms around the chest it may prevent adequate chest expansion and cause respiratory distress.6

Expose the chest to assess the adequacy of ventilation and look for further injuries.

Monitor oxygen saturations with a pulse oximeter and administer 100% high-flow humidified oxygen through a non-rebreather mask as required.

Take an arterial blood gas (ABG) to assess oxygenation and carboxyhaemoglobin levels to exclude carbon monoxide poisoning.2

Circulation

Severe burns may cause circulatory shock secondary to large fluid losses and systemic inflammatory response.2 It is also important to remember that non-burn injuries may also cause circulatory compromise (e.g. from significant haemorrhage, cardiac tamponade).

Assess blood pressure before inserting two large bore cannulas through unburnt skin and immediately correct any hypotensive shock with warm, intravenous fluids (further details later in this article).

Take routine blood tests including FBC, U&Es, LFTs, capillary blood glucose, group and save, a coagulation screen and creatine kinase levels.2

Insert a urinary catheter for fluid balance monitoring and complete a hydration status assessment.

Evaluate any areas where there are circumferential limb burns:2

- Regularly check blood flow to the limb by checking the pulses and capillary refill time, and by placing a pulse oximeter on a finger or toe of the affected limb.

- A doppler ultrasound can be used for further assessment of blood flow.

- An urgent senior review should be sought when a circumferential limb eschar is suspected.

Disability

Regularly check the patient’s core temperature and maintain it with active and passive warming as appropriate.2

Use AVPU or GCS to assess consciousness level.

Exposure

Expose the patient in sections (to minimise cooling) in order to estimate the percentage of total body surface area (%TBSA) burned and the depth of the burns.2

Give a tetanus booster if required.7

Once the patient is stable, a thorough history should be taken to assess the following points:7

- The patient’s current pain level and any other symptoms they are experiencing

- The mechanism of injury including the timing, type, and cause of the burn

- The risk of inhalation injury

- The possibility of non-accidental injury

- If tetanus prophylaxis is needed

- Their social history to assess their level of social support

- If they have any co-morbidities which may affect healing and their complications risk

Assessing burn severity

During the ‘exposure’ section of the ABCDE assessment, the severity of the burns should be assessed. This involves estimating the percentage of the total body surface area injured (%TBSA) and the depths of each of the burns.

Remember to expose in sections to keep the patient as warm as possible.

Assessing %TBSA

Accurate estimation of the percentage of the body burnt is important to allow appropriate fluid resuscitation. The morbidity and mortality of the injury are also closely related to the surface area injured.8

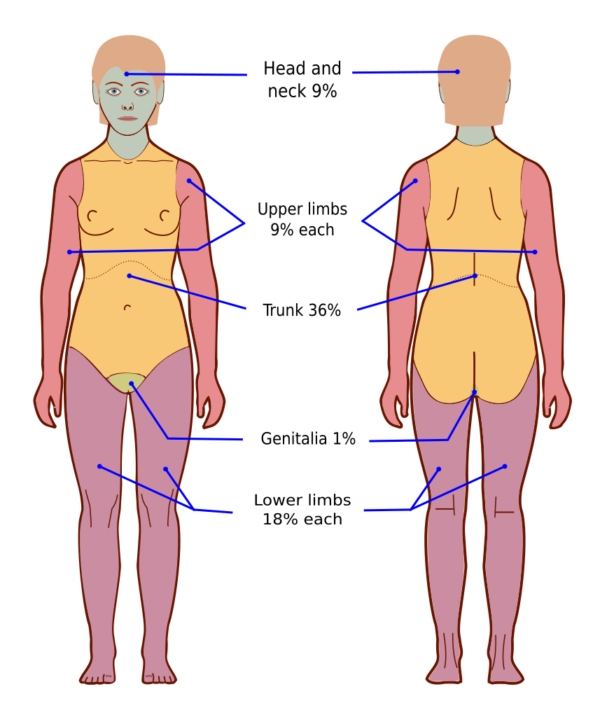

‘The Wallace rule of nines’ method

The ‘Wallace rule of nines’ method is typically used in pre-hospital and emergency medicine to quickly estimate the percentage of the body burnt in adult patients with medium to large burns.

This method involves dividing the body into sections, with each arm and the head each representing 9%, and the chest, back and each full leg representing 18% each.8 This method can be inaccurate in children.

‘Palmar surface’ method

The ‘Palmar surface’ method is useful to estimate the size of smaller burns or to estimate the size of unburnt surface area in patients with very large burn injuries.

The surface area of the patient’s entire hand equates to approximately 0.8% of the patient’s total body surface area and can be used to estimate burns coverage.8

The important thing to remember is that you need to use the patient’s hand size to estimate the percentage coverage and not your hand.

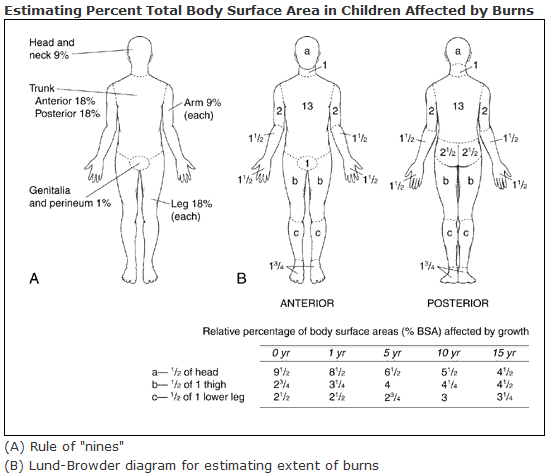

Lund and Browder chart

The Lund and Browder chart is the most accurate method as it considers different body shapes when calculating the surface area affected. This means that it is also suitable for use in paediatric patients.

The paediatric chart considers how growth affects the relative percentages of the body’s surface area. This produces a chart where different areas of the body have different percentages of total body surface area depending on the patient’s age.8

Assessing depth

After administering adequate fluid resuscitation (the depth of the burn does not guide the initial resuscitation volume), the depth of the burns should be assessed to guide further treatment.2

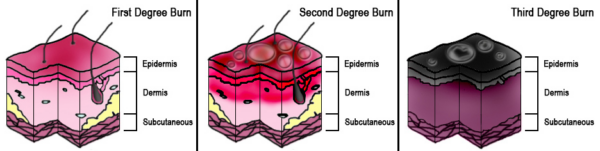

The British Burn Association has produced a new classification system that splits burn depth into four categories based on the deepest layer involved, wound appearance, if it blanches with pressure, how quickly it bleeds after a needle prick, and if pain and sensation are present.8

Table 1. Assessing the depth of burns

| Layers involved | Appearance | Blanches | Bleeding on pinprick and CRT | Sensation | Prognosis | |

|

Superficial (1st degree) |

Only epidermis damaged |

Dry & erythematous |

Yes |

Brisk bleeding and capillary refill |

Painful |

Heals in 5-10 days without scarring |

|

Superficial Partial (2nd degree) |

Epidermis & upper dermis damaged |

Wet, blistered & erythematous |

Yes |

Brisk bleeding and capillary refill |

Painful |

Heals in <3 weeks without scarring |

|

Deep Partial (2nd degree) |

Epidermis, upper & lower dermis damaged |

Dry, yellow, or white |

No |

Delayed bleeding, sluggish or absent capillary refill |

Decreased sensation |

Heals in 3-8 weeks with scarring if >3 weeks to heal |

|

Full Thickness (3rd degree) |

All skin layers to subcutaneous tissues damaged |

Dry, leathery or waxy white |

No |

No bleeding, absent capillary refill |

No sensation – painless |

Heals in >8 weeks with scarring |

This new classification system has replaced the older first, second and third-degree classification system (Figure 3).

Management of burn injuries

Wound management

Initial wound management includes:2

- Remove loose clothing and jewellery apart from anything that is adhered to the wound.

- Cool the wounds with cool tap water for 20 minutes if the wound occurred 3 hours ago or less. Do not use ice packs or other extremely cold products.

- Clean the wound with normal saline.

- Cover the wound with clingfilm loosely. Never wrap clingfilm around a limb circumferentially, as this may create a constrictive eschar and can affect distal blood flow.

Fluid resuscitation

In the first 8 to 12 hours after a burn, fluid rapidly shifts from the intravascular to interstitial fluid compartments, meaning that hypovolaemia can quickly occur if fluid resuscitation is inadequate.8 Hypovolaemia may cause reduced organ perfusion and tissue ischaemia.5

A burn percentage of more than 15% of total body surface area in adults or more than 10% in children typically warrants formal resuscitation.

Correct any clinical hypovolaemic shock on arrival then calculate the patient’s additional fluid requirement using the Parkland formula.8

Parkland formula in adults5

2-4ml x Body Weight (kg) x Total Body Surface Area Affected (TBSA) (%)

= Initial crystalloid fluid requirement for the first 24 hours

Only include partial (2nd degree) and full thickness (3rd degree) burns in the TBSA calculation.3

Fluid deficits should be corrected with Hartmann’s solution (crystalloid fluids):

- Give the first 50% of the total calculated volume over the first 8 hours since the time of the burn (not the time of hospital arrival or assessment).

- Give the remaining 50% of the volume over the following 16 hours.5

Titrate fluid requirements by closely monitoring and maintaining urine output above > 0.5ml/kg/hour in adults and around 1ml/kg/hr in children to ensure adequate end-organ perfusion.5

Analgesia

Adequate pain relief should be given early as burn injuries can be extremely painful.

This should take the form of cooling methods like running the wound under cold water and covering it with clingfilm, alongside pharmacological analgesia such as paracetamol, NSAIDs, opioids and/or ketamine as required.2

Referring to specialist burn services

The British Burn Association states that a patient should be referred to specialist burns services when any of the following circumstances are present:2 5

- All burns ≥ 2% TBSA in children or ≥ 3% TBSA in adults

- All deep partial or full-thickness burns

- All circumferential burns

- Any chemical, electrical or friction burns or cold injuries

- Any burn not healed in two weeks

- Any burn with suspicion of non-accidental injury

- Burns over the perineum, face, hands, feet, genitals, or major joints

- Pregnant patients or those with severe co-morbidities

Reconstruction

Superficial and superficial partial-thickness burns usually heal naturally within three weeks.

However, deep partial and full-thickness burns often require early excision of the necrotic tissue followed by a skin graft to aid healing and prevent hypertrophic scar tissue from forming.6

Wound debridement

Excision of necrotic tissue can be completed by the following methods:6

- Tangential excision: layers of necrotic tissue are progressively removed until the tissue becomes porcelain white, has many small bleeding points and is firm to the touch.

- Fascial excision: in full-thickness burns, all the skin and subcutaneous tissue are removed to the level of the fascia.

- Amputation: this may be used in unsalvageable limbs, very deep burns, or electrocutions.

Grafting

This debrided wound is then covered with an autograft (tissue taken from another part of the patient’s body) while in theatre. A split thickness (epidermis and upper dermis only) or full thickness (all layers of epidermis and dermis) skin graft is harvested, and then the edges of the graft are surgically joined (with glue, sutures, or staples) to the wound edges.

An allograft (from another human donor) or a xenograft (a donor from another species – typically a pig) may be used in extremely large burns which cannot be covered with the patient’s donor tissue alone. These grafts act as a temporary measure to cover the wound until more autograft tissue becomes available once other burns or previous donor sites have healed. This aims to prevent infection, wound contractures, and reduce pain.12

Treatment of scars and contractures

When formed scars or contractures have matured, further surgical treatment may include:6

- Scar release

- Local and regional flaps

- Skin substitutes

- Tissue expansion

Non-surgical treatment can include:5

- Physiotherapy

- Corticosteroid injections

- Cryotherapy

- Laser treatment

- Radiotherapy

Specific burn types

Chemical burns

The strong acids and alkalis in household chemicals can cause continuous tissue destruction until the pH is neutralised, leading to very deep chemical burns.

Acidic substances cause damage by coagulative necrosis while alkaline chemicals typically result in more extensive burns secondary to liquefactive necrosis.

Chemical burns should be immediately irrigated with warm water for at least 30 minutes and any clothes, including shoes and accessories, should be removed. Early senior review and referral to specialist burn services are essential.5

Electrical burns

Lightning strikes and contact with power lines may cause large electrical burns with visible entry and exit wounds.

The damage caused is often more serious than it first appears and there is a risk of arrhythmias and myoglobinuria developing even with low-voltage burns.

During their ABCDE assessment, all patients should have an ECG, U&Es and urine output monitoring. Creatine kinase levels should also be assessed to check for rhabdomyolysis from extensive muscle breakdown.5

Consider early surgical review in patients with electrical burns to a limb as burns may involve whole limb compartments and can cause compartment syndrome.2

Complications

Systemic complications

Systemic complications typically manifest in adult patients with burns > 25% TBSA, patients > 65 years old or < 2 years old, and those with simultaneous major trauma or smoke inhalation. The risk increases as the percentage of total body surface area burned increases.

These complications can arise secondary to a systemic inflammatory response (SIRS) where an exaggerated and dysregulated inflammatory response develops in response to a large burn injury. This may progress to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) where the inflammatory response causes end-organ failure.7

Systemic complications may include:7

- Acute lung injury: forms secondary to burns and smoke inhalation and can progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Rhabdomyolysis: forms secondary to muscle breakdown from full-thickness burns.

- Dehydration and shock

- Acute kidney injury: may result from SIRS, hypovolaemia, and rhabdomyolysis

- Electrolyte imbalances: may be caused by third space losses and kidney injury

- Hypothermia: may be secondary to large volumes of cool fluids being administered.

- Paralytic ileus

- Curling’s ulcer

Curling’s ulcer

A Curling’s ulcer forms when significant hypovolaemia from severe burns causes ischaemia of the gastric mucosa. This creates a gastric ulcer which may lead to gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation.

Starting patients on PPI therapy at admission can reduce the risk of a Curling’s ulcer forming.13

Local complications

Local complications may include:7

- Scarring: scars may be hypertrophic, and keloid scars can form in those susceptible.

- Contractures: abnormal contraction or stiffening of the muscles may reduce the range of motion and ability to move joints.

- Infection

- Circumferential eschars: eschars may reduce chest expansion if they form around the torso or reduce distal blood flow in a limb. Escharotomy may be needed.

Escharotomy

An escharotomy is a procedure where a scalpel incision is made down to the level of the subcutaneous fat but not into the muscle or fascia.

For circumferential eschars on the limbs, incisions are made to release both the lateral and medial aspects of the limb, while on the torso the incision needs to release the whole breastplate to allow adequate chest expansion.2,6

Psychosocial impact

The incident and the scarring that can follow a burn may also have a long-term psychosocial impact on the patient long after the wounds have healed, leading to:7

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Changes in body image

- Stigma

- Social isolation

Key points

- A burn is caused by heat, chemical or electrical sources damaging the different layers of the skin.

- Factors that may increase the likelihood of a burn include young or elderly age, disabilities such as cerebral palsy or epilepsy, occupations with increased heat/flame exposure, alcohol use, smoking and drug abuse.

- Superficial and superficial partial burns are both painful, have a normal capillary refill time and briskly bleed. However, superficial partial burns appear wet, erythematous and blistered while superficial burns appear dry and erythematous only.

- Deep partial and full-thickness burns both appear dry. Deep partial burns have reduced sensation and bleeding, while full-thickness burns generally have no sensation or pain and do not bleed after a pinprick or blanch under pressure.

- It is important to complete a full ABCDE assessment followed by an assessment of the depth of the burns and the percentage of the total body surface area affected (%TBSA) using an appropriate method.

- Assess the patient’s risk of an inhalation injury and check for any constricting eschars on the torso or limbs.

- Initial wound management involves cooling the wound with cold water, gently washing it with normal saline and then loosely wrapping the wound with clingfilm.

- Further management includes prompt administration of adequate analgesia, fluid resuscitation using the Parkland formula, close urine output monitoring and early referral to specialist burns services for debridement and grafting as required.

- Superficial and superficial partial burns typically heal within 3 weeks without scarring. Deep partial burns may take up to 8 weeks to heal with variable scarring. Full-thickness burns may take over 8 weeks to heal with noticeable scarring.

- Local complications can include hypertrophic scars, infection, contractures, and constrictive eschars.

- Systemic complications may include acute kidney injury, rhabdomyolysis, a Curling’s ulcer, paralytic ileus, shock, hypothermia, and electrolyte imbalances.

Reviewer

Mr David Sainsbury

Consultant Cleft and Plastic Surgeon

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Warby, R. and Maani, C., 2022. Burn Classification. Published in 2021 [online]. Available from: [LINK].

- Matthews, J. and Atwal, R. Major trauma – Burns – RCEMLearning. Published in 2021 [online]. Available from: [LINK]

- Davies, K., Johnson, E., Hollén, L., Jones, H., Lyttle, M., Maguire, S. and Kemp, A. Incidence of medically attended paediatric burns across the UK. Published in 2020 [online]. Available from: [LINK].

- World Health Organisation. Burns Factsheet. Published in 2018 [online]. Available from: [LINK].

- South West UK NHS Burn Care. Guideline on the initial assessment and management of burn-injured patients. Published in October 2018 [online]. Available from [LINK]

- Nitescu, C., Calota, D., Florescu, I. and Lascar, I.Surgical options in extensive burns management. Published in 2012 [online]. PubMed Central (PMC). Available from: [LINK].

- NICE CKS. Burns and scalds | Health topics A to Z | CKS | NICE. Published in 2020 [online]. Available from: [LINK].

- Hettiaratchy, S. and Papini, R., 2004. Initial management of a major burn: II—assessment and resuscitation.BMJ, [online] 329(7457), pp.101-103. Published in 2004. Available from: [LINK].

- Figure 1 – Jmarchn via Wikimedia Commons. Wallace rule of nines diagram. Licence: [CC BY-SA 3.0].

- Figure 2 – U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Lund-Browder Chart. Licence: [Public domain]

- Figure 3 – Persian Poet Gal. Diagram of different burn depths. Licence: [CC BY 3.0].

- healthpartners.com. Skin grafts for burn treatment | Regions Hospital. [online] Available from: [LINK]

- Siddiqui AH, Farooq U, Siddiqui F. Curling Ulcer. [Updated May 2022]. In: StatPearls [online]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: [LINK]