- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is the sudden occlusion of the artery supplying the inner retina leading to hypoperfusion of the retina, hypoxic damage, retinal cell death and visual loss.

CRAO is the ophthalmic equivalent of a stroke and is an ophthalmic emergency. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to restore retinal perfusion and minimise cellular damage and visual loss.

It has an incidence of approximately 1 in 100,000/year and predominantly affects older people (over 60 years of age).1

Aetiology

The most common cause of CRAO is embolism. The source is often from carotid artery disease or alternatively from the heart in patients with atrial fibrillation (especially in younger patients).2

CRAO can also be caused by in-situ thrombosis, which can result from atherosclerotic disease, vasculitis, inflammatory disorders, and/or hypercoagulable states.

Conditions predisposing to thrombosis include sickle cell anaemia, multiple myeloma, systemic lupus erythematosus, Factor V Leiden, polyarteritis nodosa, temporal/giant cell arteritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and Behcet’s disease among others.1

Differentiating between thromboembolic and vasculitic causes is important, as this will influence management. Rapid administration of steroids is required in cases of vasculitic CRAO (e.g. temporal arteritis).

Risk factors

Most cases of CRAO are due to thromboembolism or atherosclerotic disease.

Therefore, risk factors for CRAO are similar to the risk factors for cardiovascular disease. These include:

- Hypertension

- Smoking

- Hyperlipidaemia

- Diabetes

- Hypercoagulable states

- Male gender

In addition, carotid artery stenosis is also a significant risk factor for CRAO.

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of CRAO include:

- Sudden painless unilateral visual loss: occurs over seconds

- Amaurosis fugax: in around 10% of patients

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Past medical history: atherosclerotic disease or vasculitis

- Symptoms of temporal/giant cell arteritis: headaches, temporal tenderness, jaw claudication

Clinical examination

In the context of suspected CRAO, a thorough eye examination including fundoscopy is required.

Typical clinical findings in CRAO include:

- Profound unilateral reduction in visual acuity (usually reduced to counting fingers or less)

- Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD)

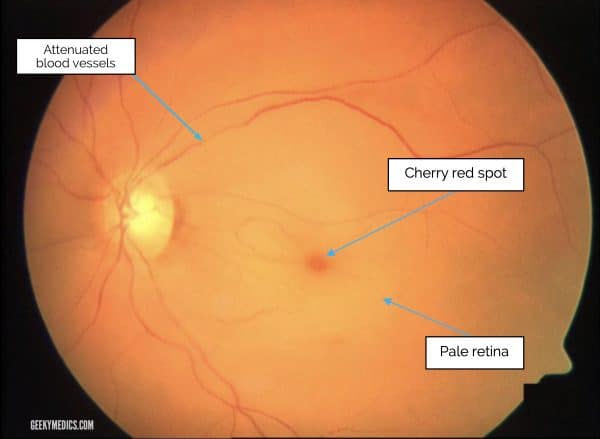

- Pale retina with a central cherry-red spot on fundoscopy

The retina appears pale due to oedema, and the cherry-red spot is from the thin fovea revealing the preserved underlying choroidal circulation.

A physical examination should also be undertaken to identify an underlying cause, paying particular attention to:

- Pulse rate and rhythm

- Blood pressure

- Carotid bruits

- Signs of temporal arteritis (scalp tenderness, nodular temporal arteries)

- Signs of connective tissue diseases that could predispose to vasculitis in younger patients

Differential diagnoses

Other causes of sudden-onset unilateral painless visual loss to consider include:2

- Retinal detachment: patients usually describe a ‘curtain’ on their visual field in one eye, some floaters and/or some flashing lights. A detached retina can sometimes be seen on fundoscopy.

- Vitreous haemorrhage: blood in vitreous visible on fundoscopy

- Retinal vein occlusion: fundoscopy will reveal vascular dilatation and tortuosity of the affected vessels, with associated haemorrhages in that area only

- Acute optic neuritis: visual loss is usually accompanied by pain on eye movements and dyschromatopsia (impaired colour vision)

Investigations

CRAO is a clinical diagnosis, but if there is any doubt then fundus fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis.

Other investigations are aimed at identifying the underlying cause.

As CRAO is an ischaemic event, investigations for CRAO are similar to those used for stroke or transient ischemic attack.3

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- ESR and CRP: to exclude temporal/giant cell arteritis

- Full blood count: to check for myeloproliferative disorders or anaemia

- Coagulation studies (PT and APTT): to screen for coagulation disorders

Depending on individual risk factors and history, other relevant laboratory investigations may include:

- HbA1c and lipid profile: to assess for underlying cardiovascular risk factors

- Vasculitic screen (ANA, ENA, ANCA, ACE): if vasculitic aetiology is suspected in younger patients

- Myeloproliferative or sickle cell disease (blood film): if any abnormalities detected on FBC or no other aetiology identified

- Hypercoagulable screen (protein C&S, factor V Leiden, antiphospholipid antibody): to look for coagulation disorders in younger patients

Other investigations

If an embolic cause is suspected, other investigations to consider may include:3

- Carotid duplex ultrasound (doppler): to look for carotid artery stenosis

- ECG: to look for atrial fibrillation

- Echocardiogram: to look for mural thrombus

- Ambulatory ECG monitoring: to look for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

Management

CRAO is an ocular emergency and prompt management is required to prevent visual loss and to protect the other eye, brain and heart from further thromboembolic events.

The aim of management is to attempt to re-perfuse ischaemic tissue as soon as possible and to institute secondary prevention early.2

All patients require an urgent referral to the stroke team and ophthalmology.

Immediate management

If inflammatory markers are elevated and/or the history and examination are consistent with temporal/giant cell arteritis, then high dose steroids should be initiated immediately.3

There are no official guidelines for the treatment of CRAO, and many therapies are of no proven benefit but have anecdotal support and are often tried.

Immediate management options include:1,3

- Ocular massage: repeatedly massaging the globe over the closed lid for ten seconds with five-second interludes may occasionally dislodge the obstructing thrombus.

- Increase blood oxygen content and dilate retinal arteries: administration of sublingual isosorbide dinitrate or oral pentoxifylline. Inhalation of a carbogen or hyperbaric oxygen.

- Reduce intraocular pressure: to increase retinal artery perfusion pressure with intravenous acetazolamide and mannitol, plus anterior chamber paracentesis.

If the patient presents within 24 hours, intra-arterial fibrinolysis through local injection of urokinase into the proximal part of the ophthalmic artery, or intravenous thrombolysis using tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) such as alteplase can be considered, although evidence for such therapies remains equivocal.1

Long-term management

Underlying risk factors should be addressed and modified:2

- Diet and lifestyle: a low glycaemic index diet, with adequate levels of vitamin B6 and B12, and regular exercise, will help prevent risk factors such as diabetes and atherosclerosis

- Smoking: offer smoking cessation

- Hypertension: should be investigated and treated

- Hyperlipidaemia: a statin may be initiated

- Atherosclerosis: low-dose aspirin may be of benefit

- Atrial fibrillation: should be investigated and treated with rate or rhythm control strategy, and anticoagulated unless the risks outweigh the benefits

- Carotid artery disease: carotid endarterectomy may be necessary depending on the degree of carotid occlusion and local policy

In the United Kingdom, the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) will need to be notified if there is a complete loss of vision in one eye. Patients may still be able to drive after clinical advice and successful adaptation to the condition.

Complications

Retinal ischaemia can lead to neovascularisation of the iris and retina around 8 weeks following CRAO.

This can lead to complications such as vitreous haemorrhage and neovascular glaucoma. Patients should be followed up to monitor for such complications up to 4 months after the ischaemic event.1

If at any stage, a patient develops neovascularisation, pan-retinal photocoagulation should be performed.4

Prognosis

Studies have shown that irreversible damage is done to the retina 240 minutes following the occurrence of CRAO.5

Over 90% of patients present with a visual acuity of counting fingers, or less. Even with prompt treatment, the prognosis is poor, although some improvement in visual acuity may be seen in the first 7 days post-CRAO in one-third of patients (with or without treatment).6

Key points

- Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is the sudden occlusion of the artery supplying the inner retina. It is an ocular emergency.

- Embolism is the most common cause of CRAO. The source is often from carotid artery disease or alternatively from the heart in patients with atrial fibrillation (especially in younger patients).

- CRAO presents with sudden painless unilateral visual loss. Fundoscopy reveals a pale retina with a cherry-red spot in the centre of the macula.

- Although the most common cause is thrombo-embolism, it is crucial to exclude giant cell arteritis (GCA) and other vasculitic causes.

- Management is focused on immediate reperfusion of the retina and long-term management of underlying risk factors.

- The prognosis for visual recovery is poor, but chances of visual recovery are higher if treatment is given early.

- Retinal ischaemia can lead to neovascularisation of the iris and retina around 8 weeks following CRAO. Patients should be followed up to monitor for such complications up to 4 months after the ischaemic event.

Reviewer

Dr Byron Lu Morrell

Ophthalmology ST2

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Varma DD, Cugati S, Lee AW, et al; A review of central retinal artery occlusion: clinical presentation and management. Eye (Lond). Jun 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Lowth M. Retinal Artery Occlusions. Sept 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Rumelt S, Dorenboim Y, Rehany U. Aggressive systematic treatment for central retinal artery occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. Available from: [LINK]

- Cugati S, Varma DD, Chen CS, et al; Treatment options for central retinal artery occlusion. Curr Treat Options Neurol. Feb 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB, Kimura A, Sanon A. Central retinal artery occlusion. Retinal survival time. Exp Eye Res. Mar Available from: [LINK]

- Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. Central retinal artery occlusion: visual outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. Sep 2005. Available from: [LINK]

Figures

- Figure 1. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Achim Fieß, Ömer Cal, Stephan Kehrein, Sven Halstenberg, Inezm Frisch, Ulrich Helmut Steinhorst. Cherry Red Spot Fiess. License: [CC-BY].