- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) describes the premalignant dysplasia of the cervical epithelium, most commonly at the squamocolumnar junction, driven by infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV). Over time, it may progress to cervical cancer, requiring chemoradiation and potential surgery.1

Cervical cancer is a common and highly preventable cancer.

This article has been written for medical students to understand the presentation and management of CIN and cervical cancer, as well as methods of prevention.

Epidemiology

Cervical cancer is the 4th most common female cancer worldwide, with an annual incidence of 604,000 and mortality of 342,000 in 2020.2 HPV-16 and HPV-18 contribute to over 70% of cervical cancer. Other high-risk types include 31, 33, 35, 45, 52 and 58, which account for an additional 20% of cervical cancers.3

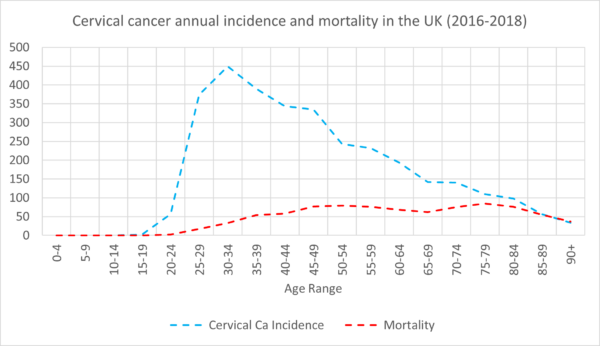

In the UK, cervical cancer is the 14th most common cancer among women of all ages, and the 2nd most common cancer among women aged 15-44. There are around 3,200 new cases and 850 deaths every year. Around 50% of cervical cancer occurs under the age of 45, with the incidence rising from the age of 15, peaking at 30-34 before decreasing with age (Figure 1).4

Aetiology

Almost all CIN and cervical cancer is driven by infection with HPV. High-risk types include HPV-16 and HPV-18, which contribute to over 70% of cervical cancer and 31, 33, 35, 45, 52 and 58, which account for an additional 20% of cervical cancers.3

Anatomy5

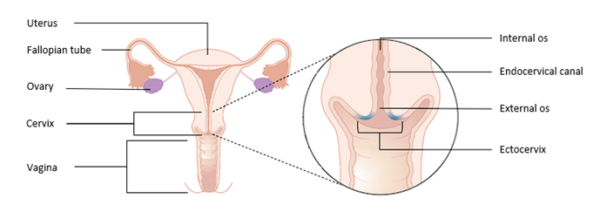

The cervix is an anatomical region which facilitates the passage of sperm into the uterine cavity and maintains sterility of the upper female reproductive tract.

The cervix is composed of two regions: the endocervical canal, and the ectocervix.

The endocervical canal is lined by mucus-secreting simple columnar epithelium and ends at a narrowing called the internal os, which marks the beginning of the uterine cavity.

The ectocervix is the distal part of the cervix which projects into the vagina and is lined by stratified squamous non-keratinised epithelium which is resistant to the low pH of the vagina. The external os marks the transition from the ectocervix to the endocervical canal.

The squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) marks the location where the squamous epithelium of the ectocervix and columnar epithelium of the endocervix meet. When the columnar epithelium of the endocervix is exposed to the acidic environment in the vagina, it undergoes squamous metaplasia.

During this process, the original SCJ everts from its original position onto the ectocervix; the area between the original SCJ and the new SCJ is known as the transformation zone.

Pathophysiology and carcinogenesis7

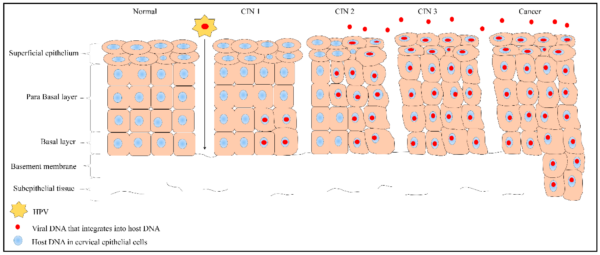

Microtrauma to the epithelial cells of the transformation zone provides HPV with access to basal keratinocytes. HPV infects these cells with its surface proteins and uses its E6 and E7 oncoproteins to inhibit the tumour suppressors p53 and pRb, resulting in uncontrolled cellular proliferation.

The ensuing accumulation of mutations results in pre-malignant cellular abnormalities, named cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Eventually, CIN can progress to invasive carcinomas (figure 3).

80% of cervical cancers are squamous cell carcinomas of the epithelial lining of the ectocervix.

20% of cervical cancers are adenocarcinomas of the glands within the lining of the cervix.

More information on the HPV life cycle can be found here.

Transmission1

HPV most commonly spreads through direct skin-skin contact during sexual intercourse.

Other, rarer, routes of transmission include:

- Contact with contaminated surfaces or objects

- Oro-genital transmission

- Perinatal vertical transmission

- Autoinoculation

Risk factors

The greatest risk factor for developing cervical cancer is HPV infection. Other factors include:1

- Smoking

- Inadequate cervical screening

- High parity

- Oral contraceptive use

- Lower socioeconomic status

- Co-infection with other sexually transmitted infections, such as HIV, herpes simplex and chlamydia

- Previous cancers of the vagina, vulva, kidneys and urinary tract

Clinical features

History1

The majority (70-90%) of HPV infections are asymptomatic and cleared within 2 years, and many women are diagnosed through routine screening.

However, cervical cancer should be considered if the woman presents with:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding (intermenstrual, postcoital, postmenopausal)

- Vaginal discharge (blood-stained, mucoid or purulent)

- Pelvic pain/dyspareunia

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Sexual history: number of sexual partners, type of sexual intercourse, use of barrier contraception, risk of other sexually transmitted infections

- Obstetric history: parity and gravidity

- HPV infection & vaccination history

Clinical examination1

A speculum examination should be performed and may show a cervical mass or an inflamed cervix which may bleed on contact. For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to performing a speculum examination and a cervical smear test.

Differential diagnoses

Table 1. Differential diagnoses to consider in the context of symptoms of suspected cervical cancer.

|

Differential diagnosis |

Clinical summary |

|

Cervicitis |

Inflamed, friable cervix prone to bleeding Commonly caused by chlamydia trachomatis |

|

Ectropion |

Red cervix (Figure 5) A benign condition involving the presence of columnar epithelium on the outside of the cervix |

|

Endometrial cancer |

May present with abnormal vaginal bleeding |

Investigations

Most cases are diagnosed through cervical screening.

Fast-track colposcopy should be offered to women with visible suspicion of cervical cancer or persistent unexplained cervical symptoms.

A gynaecology 2-week wait referral should be made in the following cases:1

- Postmenopausal women with unexplained vaginal bleeding

- Premenopausal women with persistent intermenstrual bleeding and negative pelvic exam

- Women with clinical features suggesting cervical cancer if they have not been screened, or if the bleeding persists beyond 3 months

Consider referring premenopausal women to gynaecology or genitourinary services if they have persistent abnormal bleeding and the presence of polyps, ectropion, cervicitis or warts.1

Bedside investigations11

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Cervical swab

- Sexually transmitted infection screen: swabs of the vagina, rectum and oropharynx to rule out co-infections

- Urine culture: to rule out urinary tract infection

- Pregnancy test

Laboratory investigations11

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: anaemia (due to bleeding), raised white cell count (infection)

- CRP: infection

- Urea & electrolytes: baseline, organ dysfunction in metastatic disease and renal involvement or obstruction

- Liver function tests: elevated liver enzymes may suggest liver or bone involvement in metastatic disease

- Serology: rule out co-infection with HIV, syphilis

Imaging11

Relevant imaging investigations include:

- Chest X-ray: exclude lung metastases (rare)

- CT chest, abdomen and pelvis: visualisation of metastatic lesions

- MRI pelvis: visualisation of metastatic lesions

- PET/CT whole body: detection of lymph node involvement and distant metastases

Other investigations11

Other relevant investigations include:

- Cystoscopy: may show mass impinging on bladder

- Proctoscopy: may show mass impinging on bowel

Cervical cancer screening12

The NHS cervical screening programme (NHSCP) is offered to all women aged 24.5 – 64 years.

- At age 24.5, women should receive an invitation for screening before the age of 25

- At ages 25-49, women should be offered screening every 3 years

- At ages 50-64 years, women should be offered screening every 5 years

- At ages 65 and over, women should be screened if recent cervical cytology is normal, or if they haven’t had a cervical screening test since 50 and they request one

The NHSCP requires a sample to be taken from the cervix. Three investigations are involved in the NHSCP:

- High-risk HPV (HR-HPV) testing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing detects viral DNA in the sample

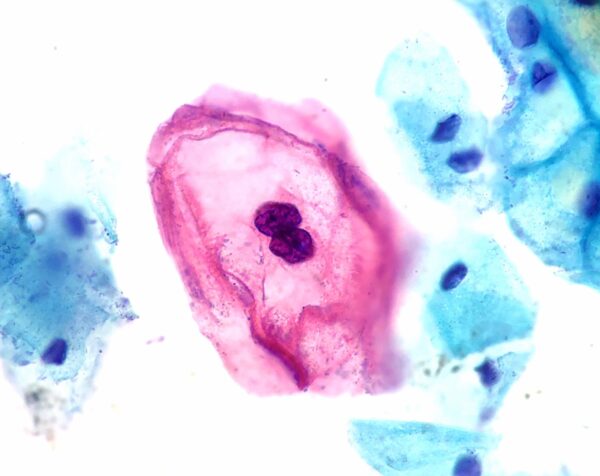

- Cytology looks at the cervical cells under a microscope to detect cellular abnormalities. Those showing HPV-driven changes are called koilocytes, and characteristically show enlarged nuclei, irregular nuclear membrane contour, hyperchromasia of the nucleus and a visible perinuclear halo (Figure 6).

- Colposcopy involves inserting a speculum and using a colposcope (a microscope with a light) to visualise the cervix in detail

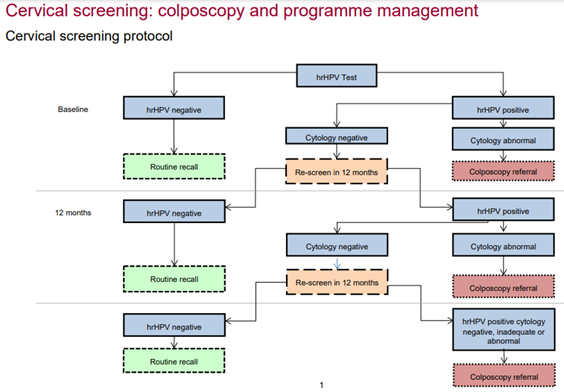

Primary HR-HPV testing was fully implemented in 2019 and replaced the Papanicolaou test (‘pap smear’) as the first step of screening. The NHSCP protocol is shown in figure 7.12

Diagnosis

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) staging1

The abnormal growth of pre-malignant cells on the cervix is called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and is classified depending on the thickness of the skin with abnormal change:

- CIN-1, or low-grade cervical lesions (LSIL): dysplasia in the basal 1/3rd of epithelium

- CIN-2, or high-grade cervical lesions (HSIL): dysplasia in the basal 2/3rd of epithelium

- CIN-3, or carcinoma-in-situ (CIS): dysplasia of more than 2/3rd of the epithelium, without invasion of the basement membrane

Cervical cancer grading

When high-grade precancerous cells invade the basement membrane, they are staged using the FIGO classification system.

Management

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia4

Treatment decisions are based upon the stage of the disease:

- CIN-1 is not routinely offered treatment and should be observed

- CIN-2/CIN-3: excision or ablation may be considered

Cervical cancer1

Treatment decisions are based upon the stage of the disease:

- Stage IA1 (microinvasive disease): can be managed conservatively

- Stage IA2-IIA (early-stage disease): radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy if the tumour is 4cm or less, chemoradiation for tumours larger than 4cm.

- Stage IIb-IVA (locally advanced disease): chemoradiation is the first line

- Stage IVb (metastatic disease): combination chemotherapy

Women with advanced or incurable cervical cancer should be managed on an individual basis with input from a multi-disciplinary team. The goal should be to treat the following issues:

- Pain: analgesia, nerve-blocking therapies or spinal therapy

- Renal failure: conservative management, percutaneous nephrostomy, retrograde stenting

- Bleeding and thrombosis

- Malodour

- Lymphoedema

Prevention1

Women should be encouraged to participate in the national screening programme and to receive the HPV vaccine.

Advice should be given regarding safe sex to reduce the risk of acquiring HPV, this includes limiting the number of sexual partners and using a condom. Note that although condoms may reduce the risk of HPV, they do not offer full protection.

Vaccination14,15

HPV vaccines contain particles from the major protein of the viral capsid. There have been several changes to the vaccination schedule, but currently, the following groups are eligible:

- Girls and boys aged 11-14: 2 doses, one given 6-24 months after the first

- Individuals aged 15-25 who did not previously receive it: 2 doses, 6 months apart

- Men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) aged 15-45: 2 doses, 6 months apart

- High-risk individuals (transgender, sex workers): 2 doses, 6 months apart

- People living with HIV (PLWH): 3 doses, all within 24 months

In 2008, the bivalent vaccine against HPV 16 and 18 was introduced in the national immunisation programme, however, this was replaced in 2012 by the quadrivalent vaccine Gardasil (against HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18). This is planned to be replaced again in 2022 by the 9-valent vaccine Gardasil 9 (against HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58) to offer more protection against cancer and genital warts.

The programme was initially aimed to provide protection for young girls before the onset of sexual activity but was expanded in 2019 to include boys. As of 2020, there is 85% coverage for girls and 53% for boys.

For individuals aged 15-25 who did not receive the vaccine, MSM aged 15-45 and high-risk groups between the ages of 15-25 are eligible for the vaccine, a schedule of 3 doses within 12 months was recommended, however from April 2022, has changed to 2 doses, 6 months apart.

Complications

Sexual problems are frequently encountered following diagnosis and treatment, including loss of libido, vaginal stenosis, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, atrophic vaginitis and pain.

Medical complications of advanced disease include pain, renal failure, thromboembolism, haemorrhage, malodour and fistula formations. Iatrogenic complications may include lymphoedema, and symptoms relating to late radiation effects of radiotherapy on the bladder, ureter and rectum.

Women diagnosed with cervical are more likely to experience psychological problems regarding coping with the diagnosis, pain, nausea, and fatigue as well as potential guilt for not attending follow-up and stigma associated with HPV infection.

Prognosis

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)4

HPV infection takes around 10 years or longer to progress to invasive carcinoma, and the progression of CIN is not linear:

- CIN-1: 90% regress with two years, 11% progress to CIN-3, 1% progress to invasive cancer

- CIN-2: 50% regress within two years, 22% progress to CIN-3, 5% progress to invasive cancer

- CIN-3: 12% progress to invasive cancer

Cervical cancer4

Mortality from cervical cancer has decreased dramatically over the last 40 years because of improved screening and treatment.

As with most cancers, a good prognostic outlook is associated with an earlier stage of disease at diagnosis and earlier age of diagnosis. Around 90% of women aged 15-39 survive their diagnosis for five years or more, compared to 25% aged 80 and over. Early-stage diagnoses have a one-year survival rate of around 96%, compared to 50% in the latest stage.

On average, over 80% of women survive their diagnosis for more than one year, over 60% survive for more than five years and over 50% survive for ten years or more.

Key points

- Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is a premalignant lesion for cervical cancer caused by HPV infection

- Cervical cancer is common, mostly common squamous cell carcinoma of the transformation zone of the cervix

- Risk factors include HPV infection, smoking, a high number of sexual partners, condomless sex and high parity

- Commonly asymptomatic and detected on routine screening, can cause abnormal vaginal bleeding

- Diagnosis involves HPV testing, cytology and colposcopy

- CIN is staged as 1, 2 or 3 according to the depth of cells affected

- Colposcopy, pelvic MRI, CT abdomen and pelvis and PET scans are used to facilitate TNM staging of cervical cancer

- CIN is managed through watchful waiting, excision or ablation

- Cervical cancer is treated by hysterectomy or chemoradiation

- Progression of CIN to cervical may take over 10 years

- The prognosis of cervical cancer depends on the stage at diagnosis and age at diagnosis

Reviewer

Dr Hayley Wood

Consultant in Genitourinary Medicine

Royal Derby Hospital

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017. Cervical cancer and HPV. Available from: [LINK]

- World Health Organisation, 2022. HPV Statistics. Available from: [LINK]

- Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Collado JJ, Gómez D, Muñoz J, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Summary Report 22 October 2021.

- Cancer Research UK. Cervical cancer statistics. Available from: [LINK]

- Prendiville W, Sankaranarayanan R., 2017. Colposcopy and Treatment of Cervical Precancer – Chapter 1., The role of colposcopy in cervical precancer.

- Cancer Research UK. Cervical cancer. Available from: [LINK]

- Mammas, I.N., Sourvinos, G. and Spandidos, D.A., 2009. Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection in children and adolescents. European journal of pediatrics, 168(3), pp.267-273.

- Balasubramaniam, S.D.; Balakrishnan, V.; Oon, C.E.; Kaur, G. Key Molecular Events in Cervical Cancer Development. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Haeok Lee, Mary Sue Makin, Jasintha T Mtengezo, Address Malata. Positive visual inspection with acetic acid of the cervix for CIN-1. License: [CC BY]

- GynaeImages. Cervical ectropion. License: [CC BY-SA]

- BMJ Best Practice. Cervical cancer – Investigations. Available from: [LINK]

- Public Health England, 2021. Cervical screening: colposcopy and programme management. Available from: [LINK]

- Ed Uthman. ThinPrep cervicovaginal cytology specimen. License: [CC BY]

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online) London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, 2022. Human papillomavirus vaccine. Available from: [LINK]

- NHS England. GOV.UK. 2022. HPV immunisation programme: changes from April 2022 letter. [online] Available from: [LINK]