- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Laryngotracheobronchitis, commonly known as croup, is an upper respiratory tract infection commonly caused by a viral infection.

Croup occurs in younger children aged 6 months to 3 years old and presents with a characteristic barking cough, inspiratory stridor and respiratory distress.

Croup is a common presentation during the winter months. It is important to identify and treat early, as the spectrum of disease ranges from a self-limiting illness (most common) to life-threatening upper airway obstruction.

Aetiology

Croup is caused by a viral upper respiratory tract infection inflaming the mucosa in the larynx. This inflammation causes airway obstruction leading to turbulent airflow resulting in audible stridor.

The airway obstruction relates to Poiseuille’s law which states that resistance to laminar airflow increases in inverse proportion to the fourth power of the radius. Therefore, a small reduction in airway radius (due to inflammation and secretions) dramatically increases resistance to airflow and therefore work of breathing.

Respiratory distress is more evident when the child becomes agitated or distressed, increasing the pressure and airflow through the narrowed structures.

Although croup can be caused by any respiratory virus, it is commonly caused by the parainfluenza viruses and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

Croup has been seen with human coronaviruses, influenza, measles, rhinovirus and far more rarely bacteria (including Mycoplasma pneumoniae).

Risk factors

Risk factors for croup include:

- Age: croup most commonly occurs in children aged 6-36 months

- Family history

- Male (the male:female ratio is approximately 1.4:1)

- Congenital airway narrowing

- Hyperactive airways

- Acquired airway narrowing

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of croup include:

- Upper respiratory tract symptoms including coryza and nasal congestion/discharge

- Fever

- Hoarse voice

- Barking cough (often described as ‘seal-like’)

- Inspiratory stridor

Clinical examination

Clinical examination should focus on confirming the diagnosis and assessing severity. Importantly, clinical examination should not agitate the child as this will worsen respiratory distress.

Most guidelines recommend minimal handling of the child. Throat examination is rarely required, however, if the diagnosis is unclear, this could be considered (except in cases of suspected epiglottitis).

A rapid ABCDE assessment should be performed to identify and manage any life-threatening features, for example, impending respiratory failure or significant airway obstruction.

Typical clinical findings in croup include:

- Increased work of breathing: intercostal and sternal recession

- Agitation: in severe croup

- Lethargy: in severe croup

Further examination can be performed once the situation is stabilised and no urgent treatment required. This may include ENT examination, an examination of the cervical lymph nodes, lung auscultation and assessment for rashes.

Assessment of severity

There are several validated tools used to assess the severity of croup, however, you should always refer to your local guidelines.

One example, based on the Westley croup score, is summarised below:

- Mild croup: no stridor at rest (may develop stridor with crying), barking cough, hoarse cry and no or mild work of breathing (recessions).

- Moderate croup: moderate stridor at rest with mild work of breathing with little or no agitation.

- Severe croup: significant stridor at rest (though this may become more silent as the obstruction worsens) with severe respiratory distress including sternal recession. The child may appear anxious, pale and tired.

- Impending respiratory failure: reduced consciousness, fatigue, listlessness, marked retractions, absent respiratory sounds, tachycardia and cyanosis/pallor.

Differential diagnoses

Important differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Epiglottitis: commonly caused by Haemophilus influenzae and presents without the barking cough seen in croup. The child will appear anxious, pale and ‘toxic’. The difficulty swallowing is associated with increased drooling, fever, and typically patients sit in an upright position. Children with suspected epiglottitis should have minimal handling, do not examine the mouth or upset the child as this may precipitate airway complete obstruction.

- Upper airway abscess (such as peritonsillar, parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal): presents with fevers, stiff neck, torticollis, drooling and ‘hot potato voice’. There is an absence of the barking cough.

- Foreign body inhalation: sudden onset stridor and respiratory distress often with a history of choking. May also present with a barking cough and stridor depending on the location of the obstruction. Importantly, there will be no fever.

Other differential diagnoses to consider include allergic reaction, injury to the airway, congenital airway anomalies, bronchogenic cyst and early Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Investigations

Croup is a clinical diagnosis and does not usually require investigations.

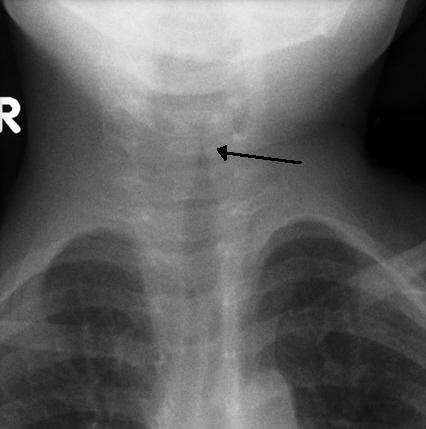

If the diagnosis is in question and differential diagnoses need to be excluded, a lateral airway X-ray or chest X-ray may be useful.

A chest X-ray in croup will demonstrate the steeple sign due to subglottic narrowing.

A lateral airway X-ray in children may be considered to rule out foreign body inhalation.

Management

Croup is a self-limiting illness. Management of croup aims to reduce the severity and avoid the need for intubation. Corticosteroids (e.g. dexamethasone) are the first-line pharmacological option to reduce the severity of symptoms.

Treatment depends on the severity of the presentation. It is important to follow local guidelines regarding the assessment of croup severity and subsequent management.

Mild croup

Management of mild croup includes:

- Oral dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg as a single dose

- If otherwise well, discharge home with a written advice sheet, safety netting and early follow up in the community (within 24 hours)

Moderate croup

Management of moderate croup includes:

- Oral dexamethasone 0.15-0.3 mg/kg as a single dose

- A period of observation to ensure improvement and no deterioration

Discharge criteria include no stridor at rest, normal oxygen saturations, normal colour, normal activity, able to tolerate fluids orally and caregivers understand when to return.

If the patient has worsened during observation, they may require nebulised adrenaline 5ml of 1:1000 and further observation.

Severe croup

Management of severe croup includes:

- Nebulised adrenaline 0.5ml/kg (up to 5ml) of 1:1000 undiluted (this can be repeated if required)

- Oxygen to correct hypoxia (if present)

- Oral or intravenous/intramuscular dexamethasone 0.3-0.6 mg/kg

- Monitoring for a minimum of four hours following a dose of adrenaline, due to the risk of rebound of symptoms after the adrenaline wears off

If children with severe croup require two or more doses of adrenaline, consider paediatric critical care review. An early review by the intensive care team is important as the patient may require intubation to protect the airway.

Criteria for hospital admission

Indications for hospital admission include:

- Severe croup

- Moderate to severe croup but with deterioration or repeated doses of adrenaline

- Toxic appearing child

- Oxygen requirement

- Inability to tolerate oral fluid intake.

Additional factors to consider include young age, number of healthcare attendances, carer anxiety or an inability for carers to bring the child back to the hospital in case of deterioration.

Complications

In most children, croup resolves within three days.

Complications are uncommon but can include:

- Secondary bacterial infections (including bacterial tracheitis, bronchopneumonia and pneumonia)

- Post-obstructive pulmonary oedema

- Pneumothorax

- Pneumomediastinum

Key points

- Croup is an upper respiratory tract infection commonly caused by a viral infection (parainfluenza and RSV).

- Croup is commonly seen in children aged 6-36 months.

- Clinical features include a barking cough (often described as seal-like), stridor and respiratory distress.

- The spectrum of severity varies from mild croup requiring no treatment, to life-threatening croup requiring nebulised adrenaline or endotracheal intubation.

- A rapid ABCDE assessment should focus on confirming the diagnosis and assessing severity. The examination should not distress the child.

- Croup is a clinical diagnosis and requires no additional investigations. Important differential diagnoses to consider include upper airway abscess, epiglottitis, and foreign body inhalation.

- Management involves dexamethasone, nebulised adrenaline, supplemental oxygen and respiratory support. Treatment depends on the severity of illness.

- In most children, croup resolves within three days and complications are uncommon.

Reviewer

Dr Thuy-Tien Vo

Paediatric Registrar

Dr Louise Lawrence

Paediatric Registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- UpToDate, Woods, Charles R. Croup: Clinical features, evaluation, and diagnosis. Jun 15, 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- UpToDate, Woods, Charles R. Management of Croup. Oct 16, 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Maloney, E. and Meakin, G., 2007. Acute stridor in children. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain, 7(6), pp.183-186.

- NSW Health. Children and Infants – Acute Management of Croup. 25 August 2017.

- The Royal Childrens Hospital Melbourne. Croup. Available from: [LINK]

- Radiopaedia / Assoc Prof Craig Hacking and Assoc Prof Frank Gaillard. Steeple Sign. License: [CC-BY-NC]. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Croup. Updated April 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. Croup. 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Oxford Handbook of Paediatrics. Oxford Handbook of Paediatrics. 2008.

- Bjornson CL, Johnson DW. Croup. The Lancet. 2008.

- Foster S. NHS GG&C Guidelines – Emergency Medicine – Croup. Available from: [LINK]