- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Eye trauma is a common presentation to the emergency department and/or the primary care setting. Each case of eye trauma requires careful clinical history and examination to rule out serious underlying injuries.

This article, aimed at the non-specialist medical practitioner, will provide a brief overview of various types of ocular trauma and the approach that should be followed in each case.

Clinical assessment of eye trauma

History

A trauma-focused ophthalmic history should include:

- Which eye/periocular structures were involved

- Approximate time and location of the injury (important if there is police involvement)

- The mechanism of the injury: mechanical, chemical or thermal

- Symptoms following the trauma: pain, decreased visual acuity/loss of part of the visual field, red eye, watering, photophobia, flashers and floaters

- Screening for intimate partner violence as ocular injuries are a common presenting feature

Additional features to establish for a mechanical injury include:

- Size, speed and nature of the object involved

- Blunt-force or sharp injury

- Use of power tools or hammer and chisel

- Use of safety goggles

- Contamination with dirt or soil

Additional features to establish for a chemical injury include:

- Name and nature of the offending agent (acid vs alkali)

- Duration of contact with the chemical

- Whether the eye was rinsed following exposure, duration of irrigation and what was used (tap water, saline, eye drops etc.)

Clinical examination

The ophthalmic examination should include:

- General inspection of the eyelid and periocular structures noting any areas of swelling, erythema, ecchymosis and lacerations. The position of the globe should be noted for enophthalmos.

- Anterior segment of the eye examination under magnification: this can be via a slit lamp, Arclight ophthalmoscope or an ophthalmoscope on the +10 setting. The structures should be examined systematically in the following order: eyelashes and lid margin, conjunctiva and sclera (note any areas of subconjunctival haemorrhage, abrasions and lacerations), cornea (before and after instillation of fluorescein to assess for abrasions and lacerations), anterior chamber for presence of a blood level (hyphaema)

- Pupil: size, shape, symmetry and testing for a relative afferent pupillary defect

- Red reflex testing with an ophthalmoscope: diminished red reflex may indicate the presence of a traumatic cataract, vitreous haemorrhage or retinal detachment

- Visual acuity assessment via Snellen chart

- Extraocular muscle movements

- Cranial nerve and neurological examination

Eyelid trauma

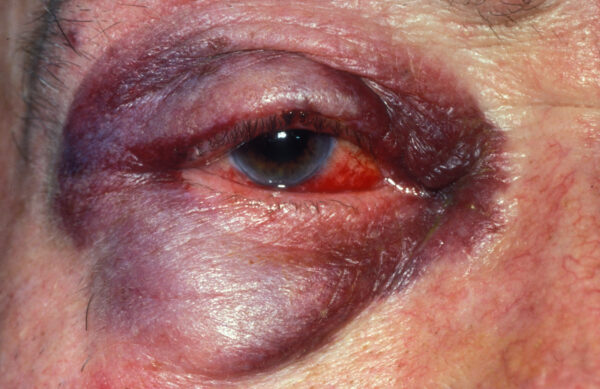

Periocular haematoma

A periocular haematoma is usually caused by blunt force to the eyelid or forehead. It typically appears more severe than the actual injury.

A careful examination must be conducted in all cases to exclude traumatic injury to the globe or orbit, retrobulbar haemorrhage or fractures to the orbital roof or base of the skull.

Periocular haematoma is a self-limiting condition. Conservative management options include cold compresses and oral analgesia.

Lacerations

Any lid laceration, however small, should prompt careful exploration of the wound and underlying eye structures. The location, orientation, dimensions and depth of any lacerations should be documented. The presence of any of these features classifies the laceration as complex:

- Full-thickness laceration or extensive tissue loss

- Injury involving the eyelid margin

- Injury to underlying ocular structures or intraorbital foreign body

- Suspected injury to the lacrimal system with medial eyelid or side of nose lacerations

- Suspected injury to the levator palpebrae superioris muscle (presents as ptosis)

- Orbital fat prolapse

Figure 2. A full-thickness, margin-involving, lower eyelid laceration of the right eye. This would be classed as a complex laceration and require specialist repair.

Investigations

Suspicion of foreign bodies which cannot be visualised merit radiological investigation (plain X-ray or CT).

Management

Management of a lid laceration should include:

- Irrigation: the laceration should be copiously irrigated with normal saline to clear debris and prevent infection

- Tetanus: confirm tetanus status and follow local guidelines

- Antibiotics for any surrounding cellulitis

- Horizontal and small, simple lacerations away from the lid can be managed laissez-faire or with cyanoacrylate glue

- All complex lacerations should be referred following initial treatment for specialist repair

Lid lacerations following power tool use

Patients who present with a small eyelid wound following power tool use should have the sclera carefully examined to exclude a penetrating eye injury.

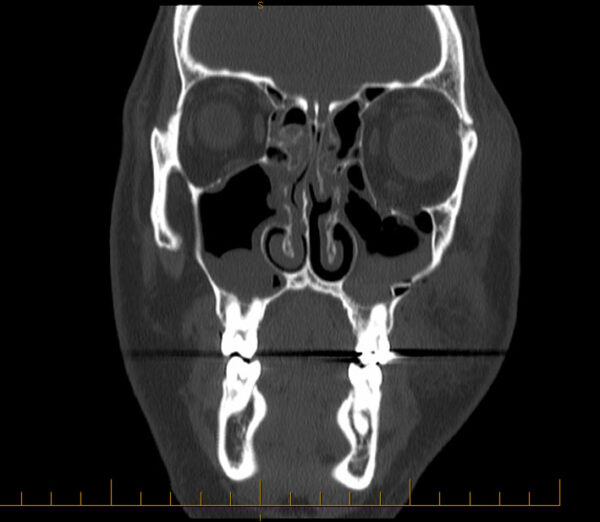

Blowout fracture

A blowout fracture typically involves blunt force trauma from an object greater than 5cm in size (e.g. a fist). The sudden increase in intraorbital pressure from such injuries creates a fracture of the relatively thin bones of the orbital floor and sometimes the medial wall.

There may be an associated injury to the globe. This commonly presents with periorbital ecchymosis, oedema and enophthalmos (globe pushed in). There may be a palpable step on palpation of the inferior orbital rim and loss of sensation over the dermatomal distribution of the infraorbital nerve. Diplopia is evident with superior and inferior restriction in extraocular muscle movement.

Investigations

CT is the imaging of choice to aid visualisation of the extent of bony fractures, prolapse of soft tissues and extraocular muscle entrapment.

Management

Conservative and medical management options include ice packs and nasal decongestants to help reduce swelling. Patients should be instructed not to blow their nose for the following 4-6 weeks. Prophylactic antibiotics may be used but remain controversial. Severe sight-threatening swelling may require treatment with oral steroids.

Diplopia often improves following the resolution of soft tissue swelling. Surgical repair is warranted if there is non-resolving diplopia or cosmetically unacceptable enophthalmos. All cases should be referred urgently for a baseline evaluation by ophthalmology and maxillofacial surgery.

Intimate partner violence

Periocular bruising and orbital floor fracture is a common presenting feature of intimate partner violence.

Abrasions and superficial foreign bodies

Small particles (metal, sand, organic material etc.) may result in a superficial abrasion to the cornea and/or conjunctiva. They may also become embedded superficially. It is important to always maintain a high index of suspicion for an intraocular foreign body (see below).

The history will often confirm the likely source of the injury and may point to the possibility of an intraocular foreign body (for example, the use of power tools without eye protection). The patient will complain of ocular surface symptoms (pain, discomfort, grittiness, epiphora and photophobia). Visual acuity is unaffected unless the injury involves the visual axis (in front of the pupil).

Clinical examination

Typical clinical features using high magnification under a white light may include:

- Conjunctival hyperaemia: this may be focal and point to the area affected or diffuse

- A clear cornea with no areas of whitening (i.e. infection)

- Visible foreign body embedded in the conjunctiva or cornea: a metal foreign body embedded for several days will develop a rust ring around it

After instilling fluorescein 2%, under a blue light areas of corneal or conjunctival epithelial injury will glow green. Abrasions may appear as large geographic areas of green staining or fine lines.

It is important to evert the lower and upper eyelid as foreign bodies may be embedded underneath. Linear vertical abrasions noted on examination suggest a foreign body embedded underneath the upper eyelid.

Management

Removing the foreign body is essential to prevent secondary microbial keratitis.

Adequate topical anaesthetic drops should be used to aid examination and removal. Irrigation with normal saline may help dislodge microscopic particles. A cotton bud can be gently rolled over any superficial foreign bodies to remove them.

A hypodermic needle should only be used with appropriate training and under slit lamp magnification. A metal foreign body may leave a rust ring following removal. A topical antibiotic ointment such as chloramphenicol should be prescribed for a few days following removal to prevent infection.

Simple abrasions without visible foreign bodies will heal within 48-72 hours. Topical prophylactic antibiotic ointment should be prescribed along with oral analgesics for comfort.

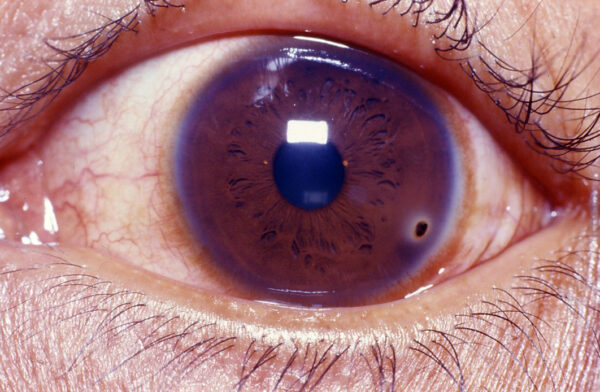

Hyphaema

Blunt trauma that compresses the globe can have a shearing effect on the blood vessels of the iris, ciliary body and trabecular meshwork. This may lead to a haemorrhage in the anterior chamber with a fluid level, known as a hyphaema. This may lead to uncontrolled elevation of intraocular pressure causing ischaemic optic neuropathy and visual loss. Therefore, prompt evaluation by an ophthalmologist is critical.

Any patient presenting with hyphaema should have a thorough evaluation for other ocular trauma as outlined above, particularly to rule out globe rupture. This is evident with poor visual acuity on presentation and may demonstrate obvious prolapse of internal ocular structures such as the iris and lens.

Non-traumatic causes of spontaneous hyphaema include neovascular diabetes mellitus, sickle cell disease, ocular neoplasms and uveitis.

Globe rupture

Severe blunt force injury to the globe may result in a globe rupture.

Management

The patient should be advised to keep upright with their head elevated as this allows blood to settle with gravity. Patients should be given a rigid eye shield, but the eye should not be patched. They should be advised to avoid any strenuous physical activity until resolution. Conservative treatment is aimed at providing comfort with oral analgesics, oral antiemetics and topical cycloplegics.

Specialist treatment of hyphema is aimed at controlling inflammation and intraocular pressure. Most hyphaemas resolve spontaneously however surgical management (anterior chamber washout) may be required in rare cases.

Chemical injury

Chemical injury to the eye is an ocular emergency requiring prompt management. These may be accidental or secondary to assault. Alkali burns tend to be more severe as it penetrates more deeply into the ocular tissues, whereas acids coagulate proteins, forming a protective barrier. Injuries involving ammonia and sodium hydroxide tend to be severe.

A thorough history should establish the exact time of the injury, the type and quantity of chemical involved and the immediate management undertaken by the patient.

Emergency treatment

Chemical injury to the eye should be managed with copious irrigation without further delay, even before conducting any further examination:

- The initial pH should be measured using a litmus strip and documented

- Topical anaesthetic is used before irrigation to ease patient distress and increases cooperation

- Crystalloid fluid (e.g. 0.9% sodium chloride or Hartmann’s solution) is preferred, but tap water can also be used to avoid delay

- The upper eyelid should be everted, or even double-everted if eyelid retractors are available, to ensure any remaining chemical or debris is washed out. A cotton bud can be used to assist in the removal of any debris.

- The eye should be irrigated for 15-30 minutes or until the eye pH neutralises to 7

Examination following irrigation

Visual acuity should be documented, and a careful examination of the periocular structures should be conducted for any associated injury.

Using high magnification under white light, the following may be observed:

- Conjunctival hyperaemia: this may be focal and point to the area affected or diffuse.

- Corneal haze: marked haze with an impaired view of the underlying iris and pupil implies severe injury. A clear cornea with an unimpaired view indicates milder injury and a better prognosis.

- Blanched blood vessels: areas of blanched blood vessels along the corneoscleral junction indicates limbal ischaemia.

After instilling fluorescein 2%, under blue light, areas of corneal or conjunctival epithelial defect will glow green.

Immediate irrigation

A chemical eye injury should be managed with immediate copious irrigation until pH neutralises, even before any other examination.

Further management

Prompt recognition and irrigation to remove any remaining chemicals are vital. Supportive measures should be aimed at controlling pain and nausea via oral analgesics and antiemetics.

Chemical injuries with corneal epithelial injury, haze or blanched blood vessels should then be referred for specialist management. This involves topical and oral therapy aimed at reducing inflammation, preventing infection and promoting re-epithelialisation. Hospital admission and surgery may be required in severe cases.

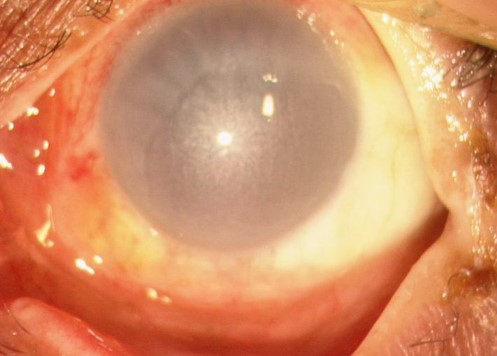

Penetrating eye injury and intraocular foreign body

A penetrating eye injury is defined as a full-thickness laceration of the globe. There may be an associated retained intraocular foreign body.

Younger males between ages 15-34 are at the highest risk of this injury compared to other demographics. The history should explore the size, shape and velocity of the object and if any protective eyewear was used. Common culprits include metal-on-metal grinding or hammering without goggles.

The clinical presentation is often severe pain, blurred or double vision and light sensitivity. Subtle cases can present with a mild blurring of vision and a foreign body sensation. Therefore it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion in all cases.

High-velocity injuries

Any high-velocity injury to the globe is a penetrating eye injury until proven otherwise.

Examination

In cases with severe periocular swelling, the eyelids should be carefully opened without applying pressure to the globe due to the risk of prolapse of intraocular structures.

A systematic examination of the eye should be undertaken. The following features on examination are potential signs of an open globe injury and should prompt cessation of any further examination to prevent further injury:

- A shallow anterior chamber and a peaked or misshapen pupil may be seen in anterior globe injuries.

- An embedded foreign body may be present at the entry site.

- Red reflex testing at arm’s length may show diminished reflex secondary to traumatic cataract, vitreous haemorrhage or retinal detachment.

Investigations

CT scan of the orbit may reveal retained foreign bodies. MRI should not be used if a metal foreign body is suspected.

Management

Any associated life-threatening injuries must be treated first. Initial treatment by a non-specialist involves placing a rigid eye shield without an eye pad to prevent further injury.

The clinician or patient should not perform any manoeuvres that may further increase intraocular pressure. Pain and nausea should be managed using appropriate oral or intravenous analgesics and anti-emetics. Systemic prophylactic antibiotics should be given due to the high risk of intraocular infection. The patient’s tetanus status should be assessed and managed appropriately.

Suspected or confirmed penetrating eye injuries should have an immediate evaluation by an ophthalmologist, as most require surgical repair. Extremely severe injuries with no visual potential are treated with evisceration or enucleation (removal of the eye).

Retrobulbar haemorrhage and orbital compartment syndrome

The orbit is a confined bony space that has very limited compliance if blood were to accumulate. A retrobulbar haemorrhage may occur following eyelid surgery or ocular trauma. This can rapidly increase the pressure within the orbit, causing compressive ischaemia to the optic nerve. This is termed orbital compartment syndrome (OCS) and is a true ophthalmic emergency.

Clinical features

Patients frequently present with proptosis and significant resistance to retropulsion. The eyelids may be very tense and difficult to open. There may be a restriction in extraocular muscle movement.

On clinical examination, signs of OCS include diminished visual acuity, relative afferent pupillary defect and reduced colour vision.

Investigations

A CT orbit will demonstrate retrobulbar haemorrhage and associated injuries, but this should be deferred if there are any signs of OCS.

Management

OCS requires immediate decompression via a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis. This is a clinical diagnosis, and any delay whilst waiting for further imaging (such as CT orbit) may cause irreversible sight loss.

Patients whose visual function is not currently threatened should have frequent monitoring of visual acuity, pupils and intraocular pressure for the first 6-8 hours. Discharged patients should be advised to carefully monitor their vision and return if there is any deterioration.

Key points

- Patients presenting with head and periocular trauma should have a thorough history and careful examination to exclude sight-threatening injuries

- Blunt force injuries to the eye may cause a blowout fracture, hyphaema or globe rupture

- A history of high-velocity impact (such as power tools) with no eye protection should prompt evaluation for a full-thickness laceration and retained intraocular foreign body

- Superficial foreign bodies can be safely removed using a sterile cotton bud and/or hypodermic needle, followed by a course of antibiotic ointment for prophylaxis

- Chemical injuries to the eye require prompt irrigation to remove any remaining chemicals and neutralise the pH

- When an open globe injury is suspected, no further examination should be carried out, and a rigid eye shield should be placed to protect the eye awaiting specialist review

- Orbital compartment syndrome is a clinical diagnosis that requires prompt decompression to prevent irreversible sight loss

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Reference texts

- Salmon, J. F. (2019). Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach (9th ed.). Elsevier.

- Bagheri, N., Wajda, B., Calvo, C., & Durrani, A. (Eds.). (2016). The wills eye manual (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Image references

- Figure 1. Community Eye Health Journal. Eyelid haematoma and subconjunctival haemorrhage following blunt force injury to the eye. License: [CC BY-NC 2.0]

- Figure 2. Community Eye Health Journal. A full-thickness, margin-involving, lower eyelid laceration of the right eye. License: [CC BY-NC 2.0]

- Figure 3. Duane Storey. Coronal CT scan demonstrating a left blowout fracture. License: [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

- Figure 4. Community Eye Health Journal. A corneal abrasion glows green when stained with fluorescein and examined under a blue light. License: [CC BY-NC 2.0]

- Figure 5. Community Eye Health Journal. A metal foreign body that has been present for a few days has developed a surrounding rust ring. License: [CC BY-NC 2.0]

- Figure 6. Rakesh Ahuja, MD. Hyphaema occupying half of the anterior chamber of the eye. License: [CC BY-SA 2.5]

- Figure 7. Community Eye Health Journal. A chemical injury demonstrating corneal haze and perilimbal blanching (ischaemia). License: [CC BY-NC 2.0]

- Figure 8. Community Eye Health Journal. A full-thickness corneal laceration with iris plugging of the wound, misshapen pupil and traumatic cataract. License: [CC BY-NC 2.0]