- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

The femoral neck is the weakest part of the femur, the largest bone in the skeleton. Neck of femur (NOF) fractures typically occur in the elderly, with a predominance for women (4:1). However, they can occur in young patients as a result of high-energy trauma.

In 2011, approximately 80,000 hip fractures were treated in the United Kingdom. This number is expected to increase to over 100,000 by 2020.1,2

Neck of femur fracture carries significant mortality with a tenth of patients dying in the first month and a third within the first year following the injury.3

Aetiology

Anatomy4

The hip joint is stabilised by a capsule, which is formed of three ligaments: the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral and pubofemoral ligaments.

The femoral head receives blood supply from three arterial sources:

- Nutrient arteries inside the bone

- Ligamentum teres

- The femoral circumflex arteries: encircle the femoral neck on top of the capsule

Causes of neck of femur fractures

The majority of neck of femur fractures occur in older patients because of low-energy trauma (e.g. a fall from standing height).

Other causes of neck of femur fractures include:5, 6

- High energy trauma: may cause neck of femur fractures in younger patients

- Pathological fractures: a fracture in a diseased bone (due to a tumour or infection)

- Reduced bone mineral density: osteopenia and osteoporosis. May be seen in younger patients due to long-term corticosteroid use, alcohol consumption or malnutrition.

- Stress fractures: less common

Classification

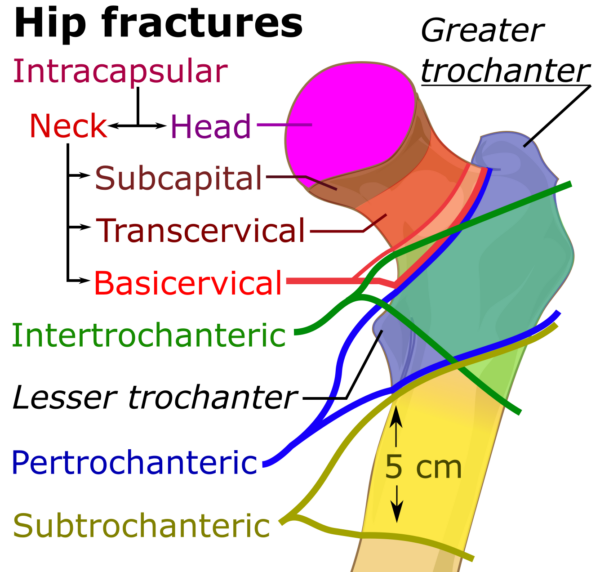

The classification of neck of femur fractures is used to guide management. Fractures can be classified by anatomical location or by the degree of displacement or angulation.

Anatomical location

A neck of femur fracture occurring proximal to the intertrochanteric line is intracapsular and involves damage to the joint capsule. As a result, the blood supply from the femoral circumflex arteries and nutrient arteries inside the bone are disrupted. The only intact artery supplying the femoral head in this situation is the artery within the ligamentum teres which is not enough to keep the femoral head viable. This can ultimately lead to avascular necrosis.

As a result, intracapsular fractures have a high risk of avascular necrosis of the femoral head and non-union of the fracture.

Extracapsular fractures are below the intertrochanteric line. These typically include intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures, where the joint capsule is not damaged and the blood supply to the fracture site is sufficient, leading to better fracture healing and an improved prognosis.

Pathological fractures tend to be in the subtrochanteric region, which is subject to the most stress.7

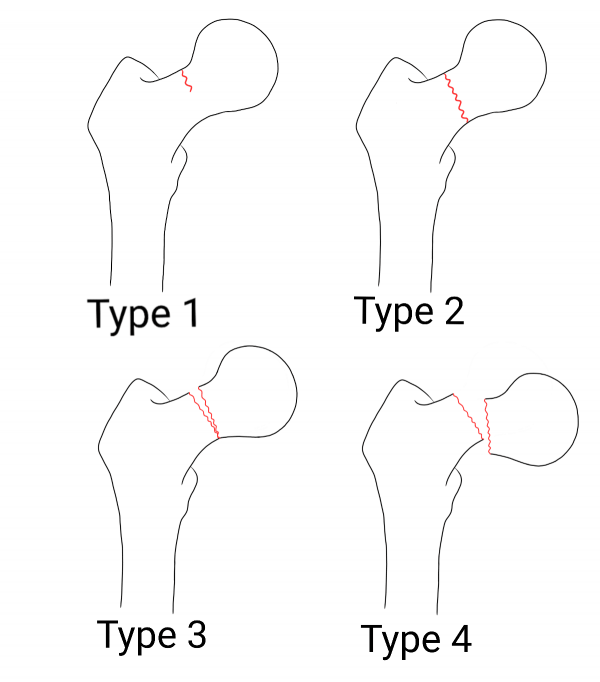

Garden classification

The Garden classification (figure 2) classifies fractures according to the degree of displacement as seen on an AP radiograph:

- Stage I: incomplete fracture line or impacted fracture

- Stage II: complete fracture line, non-displaced

- Stage III: complete fracture line, partial displacement

- Stage IV: complete fracture line, complete displacement

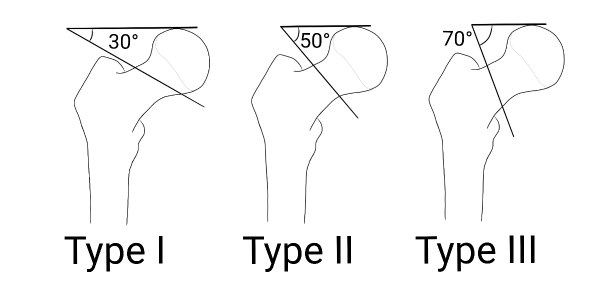

Pauwels classification

The Pauwels classification (figure 3) classifies fractures according to the angle of the fracture line from horizontal:

- Type I: between 0 and 30 degrees

- Type II: between 30 and 50 degrees

- Type III: more than 50 degrees

Risk factors

Risk factors for neck of femur fracture include:

- Age (≥65 years in women and ≥75 years in men)

- History and risk factors of osteoporosis including menopause, amenorrhoea, smoking, excessive alcohol or caffeine intake, physical inactivity, long-term or high-dose corticosteroid use

- Previous fragility fracture

- History of falls

- Poor nutrition

- Low body mass index (<18.5kg/m2)

- Dementia

- Visual impairment: which increases the risk of falls and subsequently fractures

- History of tumours (primary or secondary bone tumours, breast, bowel, prostate, kidney, lung, thyroid tumours)

Clinical features

History

Elderly or confused patients may be unable to give a history of trauma (e.g. a recent fall). This can lead to a delay in diagnosing and managing fractures resulting in a worse prognosis.11,12,13,14,15,16

The mechanism of injury should be explored when taking a history:

- Low-energy trauma: commonly a fall from standing height or less in patients over 50 years. In the case of pathological fractures and stress fractures, there may be no history of trauma.

- High-energy trauma in a young patient: the patient may have other life-threatening injuries. A (C)ABCDE approach to assess injuries and stabilise the patient with volume resuscitation may be required.7

Typical symptoms of neck of femur fractures include:

- Pain: in the hip, groin or knee

- Unable to weight-bear

- Decreased or painful mobility of the affected hip

Other important areas to cover in the history include:14,17,18

- Past medical history: previous history of cancer, bone tumours, fragility fractures, cognitive impairment, and other co-morbidities

- Drug history: medications may cause osteoporosis (e.g. corticosteroids) or have contributed to the fall (e.g. sedatives/hypnotics, antidepressants, diuretics, beta-blockers)

- Social history: lifestyle habits, home situation, living environment, activities of daily living

- Frailty scoring: using the Clinical Frailty Scale, according to the patient’s pre-morbid function

Clinical examination

Where a neck of femur fracture is suspected, an examination of the hip is necessary. However, excessive movement of the hip should be avoided as this can further displace the fracture.

Typical clinical findings in neck of femur fracture include:19,20,21

- The affected leg is shortened, externally rotated and abducted

- Palpation of the hip produces pain

- The patient is unable to perform a straight leg raise (useful for discerning occult hip fractures)

- Pain on gentle internal and external rotation of the affected leg (log roll test)

- Soft tissue symptoms: bruising and swelling in and around the hip area

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Alternative fractures such as pubic ramus fractures, acetabular fractures, femoral head and femoral shaft fractures

- Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (intermittent pain for months, pain worsens on activity)

- Dislocated hip

- Femoral head avascular necrosis

- Tendonitis of any of the muscles of the hip

- Hip bursitis

- Osteomyelitis (fever, chills, and swelling or redness in the area)

Investigations

Investigations are performed to confirm a fracture, investigate the underlying cause, and assess for complications.14,21,22

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- ECG: look for arrhythmias and coronary events that may have precipitated a fall.

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Baseline blood tests: FBC, U&E, coagulation screen

- Creatinine kinase: to look for rhabdomyolysis (if the patient had been on the floor for a long time)

- Urinalysis: to assess for urinary tract infection or hyperglycaemia

- Group and save: blood loss from a neck of femur can be significant and a blood transfusion may be required

Imaging

Imaging is used to confirm the presence of a neck of femur fracture.

Relevant imaging investigations include:

- X-rays: AP pelvis and lateral hip are the first-line imaging investigation. In patients with a history of malignancy, it’s recommended to obtain a full-length femoral X-ray looking for metastases and pathological fractures.

- MRI: the gold standard investigation to exclude a hip fracture. MRI is especially useful for detecting fractures not seen on plain X-ray.23

- CT: If MRI is not available, a CT hip can be performed. CT is recommended in patients with greater trochanteric fractures (as 20% of greater trochanteric fractures extend into the femoral neck).

Other investigations

In the case of a suspected pathological fracture caused by bony metastases, the femoral head is surgically removed during surgery and sent to pathology to ascertain the histological origins and to help identify the primary tumour.

Management

All patients with a hip fracture should be admitted to an acute orthopaedic ward and elderly patients should be assessed by an orthogeriatrician within 72 hours.24

Initial management

Initial management of a neck of femur fracture includes:25

- Analgesia: paracetamol, opioids and iliofascial/femoral nerve blocks. NSAIDs should not be used.

- Intravenous access: for fluid resuscitation, blood transfusion and the administration of medications.

- Assess and manage complications to prevent delays in surgical management (e.g. correct anaemia, anticoagulation, volume depletion and infection).

Elderly patients must also be under joint care with an orthogeriatrician.26

Surgical management

The principles of surgical management are urgent reduction and internal fixation followed by early mobilisation.

Patients should have surgery within 36 hours of admission. Benefits of early surgery include higher rates of independent living, lower rates of non-union, shorter hospital admission, reduced pain scores, lower rates of complications and reduced 30-day and 1-year mortality rates.3,14,22,24,27,28

Early mobilisation helps to prevent post-operative complications including venous thromboembolism, pressure ulcers, bronchopneumonia and other problems arising from prolonged immobility.

Intracapsular fractures

In younger (<65-years-old), or physiologically fit patients, the femoral head should be rescued. Cannulated screws (figure 4) or a dynamic hip screw (DHS) (figure 5) can be inserted.

Cannulated screws involve a set of screws being driven into the femoral head across the fracture which stabilises the fracture. A DHS is a dynamic plate screwed across the fracture line into the femoral head.

A DHS permits organised collapse of the fracture when the patient weight-bears. This improves fracture healing and union.29

In older patients, a total or hemi hip arthroplasty is recommended (figures 6 and 7). This involves the removal of the femoral head and insertion of a prosthetic replacement. The acetabulum can also be reinforced with a socket in the context of significant osteoarthritic disease.

Extracapsular fractures

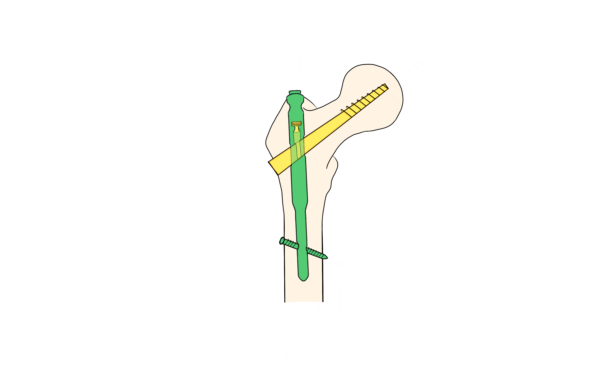

For extracapsular fractures, internal fixation is favourable with DHS or trochanteric femoral intramedullary nailing (figure 8) with screws entering the femoral head. Multi-fragmentary fractures require more complex fixation due to instability.34

Non-operative management

Although surgical management is the first-line management option, some patients may not be suitable for surgical intervention.

Indications for non-operative management include:

- Patients that are too unwell to undergo surgery

- Short life expectancy

- Delayed presentation or diagnosis of fracture with signs of healing

- Immobile patients

- Patients who decline surgery

These patients can be managed conservatively through casts, splints and traction. Periodic X-rays of the affected hip are necessary to guide management.

Non-operative management often has poor outcomes with a significant mortality rate.36

Post-operative management

The aims of post-operative management are to enhance recovery, promote early mobilisation and prevent future fractures and complications.

Table 1. Post-operative management of patients with a neck of femur fracture.

| Action | Significance |

|

Analgesia |

Poor pain control negatively impacts patient outcomes.37 Recognising pain in a patient with cognitive impairments can be challenging and requires familiarity with the patient, input from carers and awareness of behavioural and physiological cues that indicate the presence of pain (e.g. groaning, tachycardia, hypertension).14 |

|

Rehabilitation |

Patients require a multidisciplinary approach to rehabilitation.38 Rehabilitation promotes independence and reduces healthcare costs by reducing the length of hospital stay.39 |

|

Falls risk assessment |

Half of patients presenting with a first fall will have another fall within the next 12 months. Recurring falls are linked to increased risk of fractures, increased mortality, and higher rates of hospitalisation. Loss of confidence, fear of falling and diminished quality of life can further aggravate the situation.40,41 |

|

Dietetic assessment |

Protein-caloric malnutrition is a complication of surgical management and can adversely affect a patient’s health and recovery from the injury. |

|

Early mobilisation |

Patients should be encouraged to sit up in bed or chair and to mobilise on crutches early. Early physiotherapy input is important. |

|

Axial bone densitometry |

Assess for osteoporosis and offer anti-resorptive therapy to reduce risk of future fragility fractures.42,43 |

|

Antibiotic prophylaxis |

To prevent surgical site infections a significant cause of mortality.44 |

|

Thromboembolism prophylaxis |

To prevent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. |

In the United Kingdom, if a hip replacement has been performed the details must be registered with the National Joint Registry. In addition, patients should be referred for assessment and management of osteoporosis if they have suffered a fragility fracture from low-energy trauma.

Complications

Non-operative management

Complications of non-operative conservative management include:

- Fracture displacement

- Non-union or mal union

- Avascular necrosis of femoral head

- Venous thromboembolism

- Pressure sores

- Infection: pneumonia and urinary tract infections

- Death

Surgical management

Complications of surgical management can be divided into medical complications, functional complications and specific complications related to the surgical procedure.45

Medical complications of surgical management include:

- Surgical site infection

- Protein-caloric malnutrition (20-70%)

- Anaemia (24%-44%)

- Venous thromboembolism (27%/1-7%)

- Post-operative delirium (13% to 33%)

- Bleeding

- Fat embolism

Functional complications of surgical management include:

- Nerve and vessel injury

- Muscle and ligament damage

- Leg-length discrepancies

Complications related to dynamic hip screws and cannulated screws include:

- Non-union and femoral head avascular necrosis

- Soft tissue irritation caused by a lag screw pressing into soft tissue

- Screw cut out (due to the brittleness of osteoporotic bone)

Complications related to total/hemiarthroplasty include:

- Peri-prosthetic fracture, prosthetic loosening or dislocation of the prosthesis

- Acetabular wear

- Bone cement implantation syndrome

- Femoral shaft fracture

Patients with total hip arthroplasties, complex nailings and fixed intracapsular hip fractures should be followed up in orthopaedic clinics.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the health status of the patient and the type of fracture.

Healthy, young, and physiologically fit individuals with uncomplicated fractures will have a good prognosis, whereas frail elderly patients are unlikely to fully recover from a neck of femur fracture.46, 47

Even with the best care provided, around one-third of patients die within 12 months and one in ten patients die within 30 days of sustaining a hip fracture.3

Impact on patients

Neck of femur fractures have a significant impact on the quality of life and functional status of patients. Only around half of patients will return to their baseline functional status. 10 – 20% of patients will move to a residential or nursing home following a neck of femur fracture.48

Key points

- Neck of femur fractures typically occur in older patients following low-energy trauma such as a fall from standing height.

- Neck of femur fractures can be intracapsular (proximal to the intertrochanteric line) or extracapsular (below the intertrochanteric line). Intracapsular fractures have a high risk of avascular necrosis of the femoral head and non-union of the fracture.

- Common symptoms include pain in the hip, groin or knee, inability to weight-bear and decreased or painful mobility of the affected hip.

- Common clinical findings include pain on palpation, inability to perform straight leg raise, and the affected leg is visibly shortened, externally rotated and abducted.

- X-ray is the first-line imaging investigation. CT can show the fracture in better detail and MRI is the gold standard for diagnosing fractures although this imaging modality is not always available.

- Surgical options include fixation of the femoral head with cannulated screws or DHS, total and hemi hip arthroplasty and trochanteric femoral nail.

- Non-operative conservative management is available where surgical intervention is not appropriate. However, this carries a poor prognosis.

- Important complications include femoral head avascular necrosis, non-union and problems with the prosthesis.

Reviewer

Ms Deepa Bose

Trauma & Orthopaedics Consultant

University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust

Ms Gemma M Smith

ST7 in Trauma & Orthopaedics

University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Holt G et al. Changes in population demographics and the future incidence of hip fracture. Published in 2009. Available from: [LINK]

- Baker et al. Evolution of the hip fracture population: time to consider the future? A retrospective observational analysis. Published in 2014. Available from: [LINK]

- Lewis PM, Waddell JP. When is the ideal time to operate on a patient with a fracture of the hip? A review of the available literature. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Marieb and Hoehn. Human Anatomy and Physiology. 7th ed. Published in 2011.

- Solomon, Warwick and Nayagam. Apley and Solomon’s Concise System of Orthopaedics and Trauma. 4th ed. Published in 2014.

- Duckworth and Blundell. Lecture Notes: Orthopaedics and Fractures. 4th ed. Published in 2010.

- Jackson C, Tanios M, Ebraheim N. Management of subtrochanteric proximal femur fractures: A review of recent literature. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Mikael Häggström. English: Classification of hip fractures. License: [Public domain]. Available from: [LINK]

- Leyla Noury. Garden classification of NOFF

- Leyla Noury. Pauwels classification of NOFF

- Sri-On J et al. Is there such a thing as a mechanical fall? Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Jorgensen TSH et al. Falls and comorbidity: The pathway to fractures. Published in 2014. Available from: [LINK]

- Anderson KE. Falls in the elderly. Published in 2007. Available from: [LINK]

- British Geriatrics Society. The care of patients with fragility fracture. Published in 2007. Available from: [LINK]

- NHS England and NHS Improvement. 2017/18 and 2018/19 National Tariff Payment System Annex F: Guidance on best practice tariffs. Published in 2016. Updated in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- National Hip Fracture Database. Best Practice Tariff (BPT) for Fragility Hip Fracture Care User Guide. Published in 2010. Available from: [LINK]

- Carda S et al. Osteoporosis after stroke: A review of the causes and potential treatments. Published in 2009. Available from: [LINK]

- Park-Wyllie LY, Hawker GA, Laupacis A. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women: Reply. Published in 2011. Available from: [LINK]

- Maury et al. Occult fracture of the hip: a clinical and radiological correlation, orthopaedic proceedings. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Byrd JWT. Evaluation of the hip: history and physical examination. Published in 2007. Available from: [LINK]

- Green CM, Shah N. A protocol for the management of the inpatient fracture neck of femur is required. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Hip fracture management. Clinical guideline [CG124]. Published in 2011. Updated in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. The Management of Hip Fracture in Adults. Published in 2011. Available from: [LINK]

- National Hip Fracture Database. 2019 Annual Report. Published in 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Watson P et al. Improving analgesia in fractured neck of femur with a standardised fascia iliaca block protocol. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- British Orthopaedic Association. The care of the older or frail orthopaedic trauma patient. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Aqil A et al. Achieving hip fracture surgery within 36 hours: an investigation of risk factors to surgical delay and recommendations for practice. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y. Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Published in 2008. Available from: [LINK]

- Azar, Beaty and Canale. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 13th ed. Published in 2017.

- Leyla Noury. Cannulated screws of the hip.

- Booyabazooka. X-ray image of my own hip, with orthopedic implant on femur; approximately a year and a half after surgery. License: [CC-BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Mikael Häggström. X-ray of the hip of a 51 year old nurse with idiopathic avascular necrosis of the left femoral head. After hip replacement. Anteroposterior image of pelvis. License: [Public domain]. Available from: [LINK]

- Carl Jones et al. English: X-ray of the hips, with a right-sided hip replacement of the hemiarthroplasty type. License: [CC-BY]. Available from: [LINK]

- AO Surgery Reference. Proximal femur. Accessed in June 2020. Available from: [LINK].

- Leyla Noury. Trochanteric femoral intramedullary nail

- Chlebec et al. Nonoperative Geriatric Hip Fracture Treatment Is Associated with Increased Mortality: A Matched Cohort Study. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Gan TJ. Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- British Orthopaedic Association. Rehabilitation and communication with trauma patients. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Hip fracture in adults. Quality standard [QS16]. Published in 2012. Updated in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- British Orthopaedic Association. Patients sustaining a fragility fracture. Published in 2012. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Falls in older people: assessing risk and prevention. Clinical guideline [CG161]. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Banu J. Causes, consequences, and treatment of osteoporosis in men. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fracture. Clinical guideline [CG146]. Published in 2012. Updated in 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Edwards C et al. Early infection after hip fracture surgery. Published in 2008. Available from: [LINK]

- Carpintero P et al. Complications of hip fractures: A review. Published in 2014. Available from: [LINK]

- Fried LP et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. Published in 2001. Available from: [LINK]

- Tom S. E et al. Frailty and Fracture, Disability and Falls: A Multiple Country Study from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Salkeld G et al. Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: A time trade off study. Published in 2000. Available from: [LINK]