- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a species of Lentivirus, a subgroup of the retrovirus family, that preferentially infects CD4+ T helper lymphocytes, resulting in the progressive destruction of the immune system and the onset of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Despite the decline in HIV diagnoses seen in the UK during the past several years, HIV and AIDS remain a huge economic and health burden worldwide.1

This article has been written to provide medical students with the information needed to achieve the goals set out by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): identify those at risk of HIV, recognise HIV-related health issues and facilitate prompt testing and management of patients with HIV.2

Epidemiology

There are two main types of HIV, known as HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the predominant type found in the UK, whereas HIV-2 is mainly found in West Africa. For this article, references to HIV will focus on HIV-1 unless specified otherwise.

In recent years, there has been a global decline in new HIV diagnoses of 37% and a decline in HIV-related deaths of 45%. This change has also been seen in the UK, with the annual incidence falling from 6,185 in 2014 to 4,363 in 2018.3

Furthermore, the UK has successfully reached the target of diagnosing 90% of HIV positive people, providing antiretroviral therapy for 90% of those diagnosed, and achieving viral suppression in 90% of those on treatment. This global ‘90-90-90‘ target was set by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) in 2014.1

The demographic groups most affected by the virus vary. However, in the UK, HIV is most prevalent among men who have sex with men (MSM) and black-African heterosexual men and women.2

Aetiology

The life cycle of HIV, its progression to AIDS, and the mechanisms by which it causes disease are well-characterised. Knowledge of this is useful for understanding its clinical presentation and treatment.

Pathophysiology

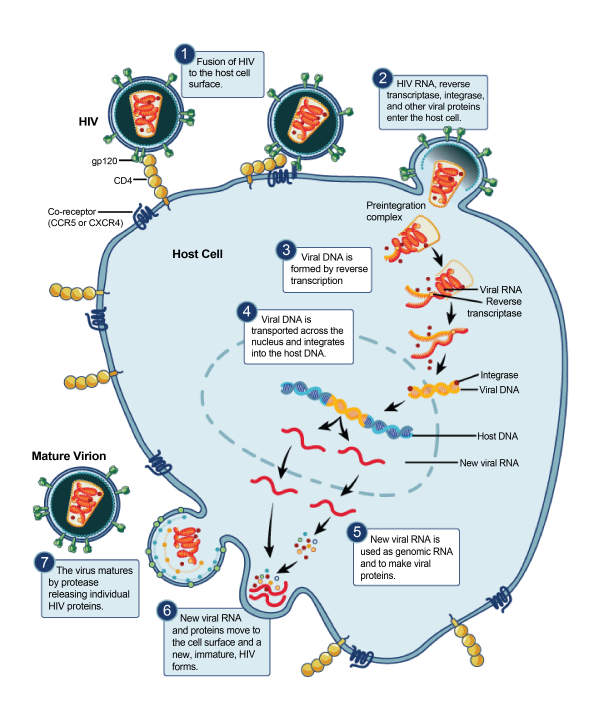

The HIV life cycle provides several different targets for pharmaceutical intervention, as described below and in figure 1.4

- Binding: viral protein gp120 on the surface of HIV binds host glycoprotein CD4+ and host co-receptor CCR5 or CXCR4. This is blocked by CCR5 antagonists.

- Fusion: viral protein gp41 penetrates the cell membrane, allowing the fusion of the virus and cell. This is blocked by cell fusion inhibitors.

- Reverse transcription: viral reverse transcriptase converts HIV single-stranded RNA to double-stranded DNA. This is blocked by non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs).

- Integration: viral integrase enzymes allows HIV DNA to insert into the host DNA. This is blocked by integrase inhibitors.

- Replication: host machinery transcribes and translates new HIV RNA and polyproteins.

- Assembly: the new HIV proteins and HIV RNA move to the cell membrane and assemble the immature, non-infectious virion.

- Budding: the new HIV virion exits the cell and viral protease cleaves the long HIV protein chains to form the mature, infectious virion. This is blocked by protease inhibitors.

Natural history

Stage 1: Primary HIV infection (seroconversion)

HIV binds to a CD4+ receptor found on the surface of T helper lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells (collectively named CD4+ cells).2

Within one day of its life cycle, the infected CD4+ cell dies and releases large numbers of new virions, which disseminate through the blood to infect more CD4+ cells, primarily in lymphoid tissue. This period develops within 2-4 weeks after exposure, during which time there is a high level of viral replication, making the individual highly infectious.5

The immune response to primary HIV infection (PHI) can cause mild-to-moderate non-specific symptoms, called seroconversion illness. These symptoms are often described as being similar to flu or infectious mononucleosis and commonly include muscle aches, headache and fatigue.5

Stage 2: Chronic HIV infection (asymptomatic infection/clinical latency)

During the second stage, also named asymptomatic HIV infection or clinical latency, the immune response controls the virus, limiting the symptoms despite a persistent low level of viral replication.

Though the individual is not displaying symptoms, they are infectious. Although the timeline may vary between individuals, this asymptomatic stage can continue for 10-15 years, with symptoms only presenting when the host’s ability to replenish CD4+ cells wanes. 5

Stage 3: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

When the persistent HIV infection compromises the ability of the immune system to replenish CD4+ cells, the CD4+ cell count drops below 200 cells/µL, which is sufficient for a diagnosis of AIDS.2

At this advanced stage, the ability of the immune system to combat infection is severely compromised and the infected individual will become susceptible to opportunistic infection and malignancy. Such AIDS-defining illnesses and AIDS-related complications can be found below.

If left untreated, AIDS will cause death within around 20 months.5

Transmission

As with all infectious diseases, understanding the transmission mechanisms is crucial to breaking the chain and curtailing the spread of HIV.

HIV spreads from HIV-positive individuals through infected bodily fluids, most commonly through anal or vaginal intercourse. An estimated 75% of cases worldwide are transmitted through sexual activity (vaginal, anal and oral), which highlights the importance of promoting safe sexual practice in preventing the spread of HIV.2

Other mechanisms include vertical transmission (from an infected mother to child during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding), and inoculation (via contaminated needles, blood/blood products and occupational exposure).2

It should be noted that HIV cannot be spread through social interactions such as shaking hands and kissing or by a vector (such as insects). In addition, oral transmission is rare and typically associated with concurrent oral pathology.2

Risk factors

A thorough clinical history should be taken of the patient’s presenting symptoms alongside their risk factors for HIV infection.

Demographic groups that are considered high risk for HIV infection include:2

- Men who have sex with men (MSM)

- Female sexual contacts of MSM

- Those originating from areas with a high prevalence of HIV

- Those in current or former serodiscordant relationships (in which a HIV-negative individual is partnered with a HIV-positive individual)

Lifestyle and social risk factors include:

- Intravenous drug use

- Occupational exposure (such as accidental needlestick injury)

- Sexual risk factors such as unprotected anal or vaginal sex with one or multiple partners, and having another sexually transmitted infection such as hepatitis B or hepatitis C.2

Furthermore, a thorough medical history should also be taken to identify the possibility that the patient may have received an unsafe blood transfusion or transplant.

Clinical features

This section provides information on what should be considered when suspecting HIV infection, including what information should be gathered from the clinical history and what signs and symptoms may present in the context of both primary and long-standing HIV infection.

Clinical features of primary HIV infection (seroconversion)

Seroconversion illness develops in over 60% of patients in the primary stage of HIV infection.

As the common symptoms are non-specific, UK national guidelines for HIV testing recommend HIV testing should be administered to patients presenting with glandular fever-like symptoms, fever of unknown origin, lymphadenopathy and unexplained weight loss, unexplained neutropenia, anaemia and thrombocytopenia.3

Typical symptoms of primary HIV infection (seroconversion) include:

- Fever (80%)

- Malaise (68%)

- Arthralgia (54%)

- Loss of appetite (54%)

- Maculopapular rash (51%)

- Myalgia (49%)

- Pharyngitis (44%)

- Oral ulcer (37%)

- Weight loss >2.5kg (32%)

Clinical features of longstanding HIV infection

HIV should be considered in patients who have experienced one or more of the following symptoms in the past 3 years, or if a single symptom is severe or resistant to treatment.

Table 1. An overview of the clinical features of longstanding HIV infection.

| System | Symptom/ sign |

| Constitutional | Fever/sweats |

| Weight loss | |

| Lymphadenopathy (especially if >3 months, occurring in 2 or more extra-inguinal sites) | |

| Haematology | Unexplained neutropenia |

| Unexplained anaemia | |

| Unexplained thrombocytopenia | |

| Respiratory | Cough |

| Breathlessness | |

| Infection with pneumocystis jirovecii, tuberculosis, bacterial pneumonia | |

| Neurological | Confusion |

| Personality change | |

| Seizures | |

| Focal neurological symptoms | |

| Oral Conditions | Candidiasis (figure 2) |

| Aphthous ulcers | |

| Hairy leukoplakia (figure 3) | |

| Gingivitis | |

| Dental abscess | |

| Gastrointestinal | Oesophageal candidiasis |

| Diarrhoea | |

| Dermatological | Dark purple/brown skin lesions (Kaposi’s sarcoma) (figure 4) |

| Fungal skin and nail infection | |

| Pityriasis versicolor | |

| Shingles | |

| Warts | |

| Genito-urinary | Candidiasis |

| Herpes simplex | |

| Warts | |

| Malignancy | Dark purple/brown intradermal skin lesions |

Clinical features of AIDS

AIDS can be defined as the development of one or more AIDS-defining illnesses in the presence of HIV infection or by a CD4+ count <200 cells/µL. 2

A non-exhaustive list of AIDS-defining illnesses include:

- Pneumocystis pneumonia (pneumocystis jirovecii)

- Kaposi’s sarcoma

- Cryptococcal meningitis

- Cerebral toxoplasmosis

- Cerebral lymphoma

- Cytomegalovirus retinitis

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Oesophageal candidiasis

- Tuberculosis

- Primary central nervous system lymphoma

Investigations

NICE recommends testing patients who belong to at-risk groups, those presenting with another sexually transmitted infection, new patients at a GP practice in an area of high prevalence as part of routine antenatal care, and for those who request it.

Clinical judgement and patient discussion should dictate when and where HIV testing is performed. Those suffering from symptoms indicative of a serious HIV-related condition should be admitted for urgent specialist assessment, with HIV testing being a priority.

In other cases, testing may be done in primary care, sexual health clinics, or appropriate HIV charities, depending on appropriate need and patient preference. Generally, results are available within 72 hours in primary care, on the same day in genitourinary medicine clinics, and under one-hour in specialist charities.2

There are two main methods for HIV testing:

- Laboratory-based tests on patient venipuncture samples (largely 4th generation tests)

- Point of care tests (largely 3rd generation tests).

The most used assay is the 4th generation HIV test, which detects the presence of HIV IgM and IgG antibodies and the viral p24 antigen. A positive result necessitates a second sample for confirmation and a negative test result 4 weeks after exposure may be reassuring, but still requires a repeat test at 12 weeks post-exposure to definitively exclude HIV infection.

The 3rd generation test is employed in point-of-care tests and self-testing, in which samples are taken from a finger prick or mouth swab. These tests detect HIV IgM and IgG antibodies with increased sensitivity during early seroconversion and results can be ready in under an hour.

This test is more likely to have false positives, so a positive result should be confirmed with laboratory tests (quantitative PCR to measure viral load). A negative result should be considered in the context of a 90-day window period; for exposures within this period, a second test is required to exclude HIV infection.2

Pre-test and post-test counselling

According to UK HIV testing guidelines, lengthy pre-test counselling is not required unless requested. However, the patient should always be made aware of what is being tested, the benefits of testing, details of how the results will be given, and their implications.3

Pre-test counselling should aim to determine the level of risk (travel history, sexual history, intravenous drug use etc.) and explore the benefits and difficulties of the test. Benefits of the test will include anxiety reduction and the ability to begin future planning, including how to avoid transmitting to others.

Difficulties may include dealing with a positive diagnosis, the potential effect on employment and difficulties associated with disclosure and social stigma. 3

Post-test counselling should preferably be face-to-face, especially if the patient has mental health issues, is at risk of suicide and is younger than 16. Counselling should aim to review the test result and promote risk-minimising behaviours.

Patients should always be informed if their test is negative, and they should be made aware of the detection window period and the potential need for repeated testing. For positive test results, patients should be reassured that effective treatment can prevent illness and further transmission. 3

Management

There is currently no cure for HIV, and management focuses on early initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), which aims to suppress viral replication to the point where it is undetectable and cannot be transmitted.

In addition, opportunistic infections should be treated appropriately and acute symptoms of AIDS (as previously discussed) necessitate hospital admission.

Antiretroviral therapy

HIV is highly mutagenic and can quickly develop drug resistance, so ART comprises a minimum of 3 different drugs to target different parts of the HIV life cycle.

The regimen of choice contains a backbone of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (classically tenofovir disoproxil and emtricitabine) combined with either an integrase inhibitor, a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor or a boosted protease inhibitor.9

Table 2. An overview of antiretroviral therapy for HIV.

| Drug Class | Drug Name |

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor | Emtricitabine |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | |

| Abacavir | |

| Lamivudine | |

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor | Efavirenz |

| Nevirapine | |

| Rilpivirine | |

| Protease inhibitor | Atazanavir |

| Darunavir | |

| Ritonavir | |

| Integrase inhibitor | Dolutegravir |

| Elvitegravir | |

| Raltegravir | |

| CCR5 antagonist | Maraviroc |

| Fusion inhibitor | Enfuvirtide |

If a patient continues to deteriorate (clinically or as represented by a raised viral load or decreased CD4+ count), their regimen may be changed according to previous response to treatment, tolerability, and drug interactions.

Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy can be serious or life-threatening, but medication should not be stopped without specialist advice.

Potential adverse effects include hypersensitivity, mood/behaviour/sleep changes, hyperlipidaemia, lipodystrophy, renal impairment, hepatic toxicity, peripheral neuropathy, bone marrow suppression and pancreatitis.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis

Adults at high risk of HIV may benefit from pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which is a combination of emtricitabine with tenofovir disoproxil that is taken daily before exposure to the virus to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition. Tenofovir disproxil may be used alone for HIV-negative individuals when emtricitabine is contraindicated.9

At-risk groups who should be offered PrEP include men or transgender individuals who have sex with men and HIV-negative sexual partners of HIV-positive individuals with a detectable or unknown viral load.

Post-exposure prophylaxis

Occupational and sexual exposure to HIV is a medical emergency that requires prompt treatment with a course of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP).

PEP is a course of emtricitabine, tenofovir disoproxil and raltegravir which should be initiated as soon as possible (no later than 72 hours following exposure) and continued for 28 days.10

PEP is not recommended for human bites or community needlestick injuries unless the donor is known to be highly viral or high risk.2

Patient support and HIV monitoring

Patients diagnosed with HIV will require advice and support, as well as close monitoring of their CD4+ levels to follow disease progression.

Advice should be given regarding appropriate HIV specialist services, HIV charities and local services for safer intravenous drug use, if appropriate. In addition, patients should be supported to minimise the risk of transmission through the discussion of safer sexual practices and medication adherence.

Pregnant women should be assured that medication adherence drastically reduces the risk of transmission to their children, and patients should be made aware of the British HIV Association’s endorsement of the ‘Undetectable=Untransmittable (U=U)’ consensus: a HIV-positive individual with sustained undetectable levels of HIV in their blood cannot transmit the virus to their sexual partners.10

For HIV-positive individuals, their progress should be monitored every 3-6 months for early disease and every 2-3 months in late disease. This should include assessment for opportunistic infection, viral load (PCR test for HIV RNA) and CD4+ count.

An increased viral load indicates increased viral replication, possibly caused by non-adherence to medication or viral drug resistance. CD4+ count is particularly useful to determine the degree of immunocompromise and risk of opportunistic disease; a CD4+ count >500 cells/µL represents little risk, whereas a count of <200 cells/µL is sufficient for a diagnosis of AIDS and associated risk of HIV-related cancer and illness.2

Prognosis

Life expectancy for those living with HIV is lower than the general population but has lengthened over time as the effectiveness and tolerability of ART has improved.

Early initiation and strict adherence to ART is key. Poor adherence can result in drug resistance and failure to control the virus, resulting in a steady decline in CD4+ cells and the onset of constitutional symptoms, malignancy, and opportunistic infection. The virus is suppressed within 3-6 months of ART initiation.2

Complications

As a result of HIV infection and AIDS, the host immune system is severely compromised, increasing the risk of developing a wide range of opportunistic infections, which can cause severe health complications and death.

Table 3. An overview of the complications of HIV infection and AIDS.

| System | Illness | Description |

| Respiratory | Pneumonia |

Pneumocystis carinii Most common life-threatening opportunistic infection in AIDS |

| Tuberculosis | ||

| Gastrointestinal | Oral/oesophageal candidiasis | Candida infection |

| Hepatomegaly | Viral hepatitis or drug cause | |

| Chronic diarrhoea | Variety of bacteria | |

| Perianal disease | HSV ulceration | |

| Neurological | Meningoencephalitis | Transient, associated with acute HIV |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | |

| Eye | CMV retinitis | |

| Dermatology | Kaposi’s sarcoma |

Key points

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infects the immune system and results in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

- Despite declining HIV diagnoses in the UK and worldwide, it remains a large economic and health burden.

- High-risk groups include: men who have sex with men (MSM), female sexual contacts of MSM, black-African heterosexual men and women, HIV-negative individuals in serodiscordant relationships, and those with occupational exposure.

- Primary HIV infection can present with seroconversion illness within 2-4 weeks of exposure, symptoms can include fever, fatigue, maculopapular rash and lymphadenopathy.

- Long-standing HIV infection can present with a diverse range of symptoms resulting from an impaired immune system, opportunistic infection and malignancy.

- AIDS is diagnosed by a CD4+ count <200 cells/µL, or the presence of one or more AIDS-defining illnesses.

- HIV testing uses combinations of serological testing, antigen detection and viral load measurement.

- HIV has no cure, and treatment centres upon a combination of antiretrovirals to suppress viral replication.

- Adherence is key to effective treatment and should be emphasised along with lifestyle and risk factor modification.

- HIV-positive patients should be monitored every 3-6 months in early disease and 2-3 months in late disease, to assess for opportunistic infection, changes in viral load and CD4+ count.

- Life-expectancy is lower for HIV-positive individuals but is significantly improved with early initiation and strict adherence to antiretroviral therapy.

- Complications are caused by the destruction of the immune system resulting in opportunistic infection, malignancy and death.

Reviewer

Dr Steven Laird

Consultant Physician in Infectious Diseases

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Avert (2019) HIV and AIDS in the United Kingdom. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) HIV infection and AIDS. Available from [LINK]

- British HIV Association (2020) BHIVA/BASHH/BIA Adult HIV Testing Guidelines 2020. Available from [LINK]

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (2010) HIV Replication Cycle. License: [CC-BY]. Available from [LINK]

- AIDSinfo (2019) The Stages of HIV Infection. Available from: [LINK]

- CDC, Sol Silverman, Jr.(1999) Candidiasis in HIV infection. License: [Public domain]. Available from [LINK]

- CDC, J.S. Greenspan, Sol Silverman, Jr.(1987) Oral hairy leukoplakia in HIV infection. License: [Public domain]. Available from: [LINK]

- CDC (1986) Kaposi’s Sarcoma. License: [Public domain]. Available from: [LINK]

- Joint Formulary Committee (2020) British National Formulary- HIV Infection. Available from: [LINK]

- British HIV Association (2018) BHIVA Encourages Universal Promotion of Undetectable=Untransmittable (U=U). Available from: [LINK]