- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Hyperparathyroidism occurs when there is an excess of parathyroid hormone (PTH) being secreted from the parathyroid glands in the neck.

It is a prevalent condition seen in both primary and secondary care as primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcaemia, followed by malignancy.1

Aetiology

Normal physiology

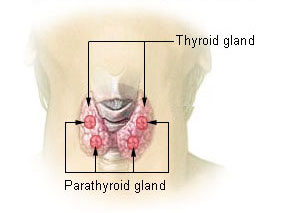

The parathyroid glands sit in the neck, on the posterior surface of the lateral lobes of the thyroid. Most adults have four, which are commonly described in two pairs (the superior and inferior parathyroid glands), although their positions in the neck can be highly variable.2

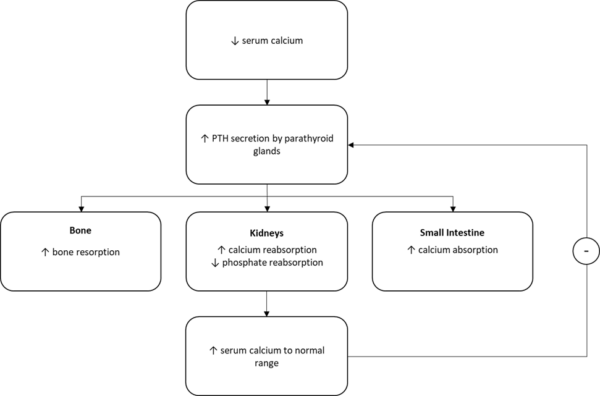

Normally, the role of the parathyroid glands is to regulate serum calcium and phosphate levels via the secretion of PTH.

The chief cells of the parathyroid glands are responsible for the synthesis and secretion of PTH, as well as the sensing of changes in serum calcium levels via the calcium-sensing receptor.

In response to hypocalcaemia, secretion of PTH is increased. PTH then raises serum calcium levels by acting on various organs throughout the body:

- Bone: promotes bone resorption and thus release of calcium into the blood

- Kidneys: stimulates calcium reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule. It also inhibits phosphate reabsorption, decreasing serum phosphate

- Small intestine: indirectly increases absorption of calcium by stimulating 1α-hydroxylase, the enzyme that activates vitamin D in the kidneys

The subsequent rise in serum calcium then reduces PTH secretion, an example of a negative feedback loop.4

Classification of hyperparathyroidism

In hyperparathyroidism, the above homeostatic mechanism becomes decompensated, and the secretion of PTH is inappropriately high.

There are several causes for this, leading to three different sub-types of hyperparathyroidism.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common of the three types and is driven by a pathology of the glands. Here, one or more of the parathyroid glands is over-secreting PTH despite normal serum calcium, which over time leads to hypercalcaemia.

The aetiology can be adenoma (85%), hyperplasia (14%, may be associated with other conditions such as multiple endocrine neoplasias), or carcinoma (<1%).

Secondary hyperparathyroidism

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is due to a disorder in calcium-phosphate-bone metabolism.

In response to low serum calcium levels as a result of another condition, commonly chronic kidney disease or vitamin D deficiency, the parathyroid glands secrete PTH. This may or may not normalise serum calcium levels, depending on the underlying condition.

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism may occur following a prolonged period of secondary hyperparathyroidism. In response to chronic PTH secretion, the glands may become hyperplastic and begin to secrete PTH autonomously. This can lead to hypercalcaemia as in primary hyperparathyroidism, especially if the underlying condition impairing calcium metabolism is treated.1,5

Table 1. A summary of the differences between the types of hyperparathyroidism

| Type | History | Blood test results |

| Primary hyperparathyroidism | Often asymptomatic, may have a family history if associated with a genetic condition like MEN | ↑PTH ↑Ca2+ |

| Secondary hyperparathyroidism | Conditions affecting calcium metabolism such as vitamin D deficiency, CKD or nutritional calcium deficiency | ↑PTH ↓Ca2+ |

| Tertiary hyperparathyroidism | As for secondary, often with evidence of recent treatment of the condition such as vitamin D replacement in deficiency | ↑PTH ↑Ca2+ |

Risk factors

Most primary hyperparathyroidism is sporadic. Risk factors include being a post-menopausal woman, having previous radiation exposure to the neck, and taking lithium. The condition may also be associated with inherited disorders such as MEN.6

Secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism are associated with conditions affecting calcium metabolism (e.g. chronic kidney disease).

Clinical presentation

History

Primary hyperparathyroidism is commonly asymptomatic and picked up incidentally on blood tests.7

However, as the serum calcium increases, so does the probability of having symptoms. When present, the symptoms are often non-specific and the same as the symptoms of hypercalcaemia regardless of the underlying cause.

Typical symptoms of hypercalcaemia include:8

- Fatigue

- Polyuria and polydipsia

- Constipation

- Abdominal pain

- Vomiting

- Confusion

- Depression

- Bone pain

- Renal stones

Mnemonic

The features of hypercalcaemia may be remembered by the mnemonic “stones (renal stones), bones (bone pain), moans (abdominal pain and constipation) and groans (psychiatric – lethargy, depression)”.9

It is important to remember, however, that in most cases the symptoms of hypercalcaemia are mild and non-specific. Renal stones and bone pain suggest chronic hypercalcaemia.

Clinical examination

On examination, it is uncommon to find clinical signs of hypercalcaemia. On palpation, there may be evidence of abdominal or bony tenderness.

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnoses for primary hyperparathyroidism are the other causes of hypercalcaemia.

The most important differential to exclude is malignancy, which is the second most common cause of hypercalcaemia. The serum PTH is a useful test for this, if it is high or inappropriately normal (remember PTH should be suppressed when serum calcium is high) then the diagnosis is likely to be primary hyperparathyroidism, if it is low then malignancy is more likely.

Using the serum PTH is also useful in classifying the other causes of hypercalcaemia into PTH-dependent and PTH-independent.

Table 2. The differentials for hypercalcaemia are classified by serum PTH result (note secondary hyperparathyroidism is not included as it does not result in hypercalcaemia).10

| PTH-dependent (↑ or high-normal PTH) | PTH-independent (↓ or low-normal PTH) |

| Primary hyperparathyroidism | Malignancy (most commonly breast, lung or myeloma) |

| Tertiary hyperparathyroidism | Medications (including thiazide-type diuretics and vitamin D) |

| Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia (an uncommon genetic condition causing benign hypercalcaemia) | Granulomatous diseases – including sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, GPA |

|

|

Other endocrine disorders including hyperthyroidism and acromegaly |

| Rhabdomyolysis |

Investigations

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Corrected calcium: should be measured in patients with suspected primary hyperparathyroidism (such as those with symptoms of hypercalcaemia, osteoporosis or fragility fracture, or a renal stone)

- Serum PTH: measure serum PTH with a paired corrected calcium. This is helpful in suggesting a cause for hypercalcaemia. Primary hyperparathyroidism will show raised or inappropriately normal PTH. A low PTH suggests a PTH-independent cause of hypercalcaemia such as malignancy.

- Vitamin D: if low, offer supplements

- Urea & electrolytes: advanced chronic kidney disease is a common cause of secondary hyperparathyroidism

Corrected calcium

Corrected calcium is also referred to as albumin-adjusted serum calcium.

This is used because only 50% of serum calcium is in the free ionised form, which is biologically active. 40% is bound to proteins such as albumin while 10% is bound to anions.4 Thus, serum calcium without correction can be spuriously abnormal in those with albumin abnormalities.

NICE recommend that direct ionised calcium testing should not be used to diagnose hyperparathyroidism.11

Other relevant specialist laboratory investigations may include a 24-hour urinary calcium excretion test or calcium: creatinine clearance ratio to exclude familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia (FHH).1,11

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:11

- DEXA scan: to assess for reduced bone mineral density (osteoporosis)

- Ultrasound of renal tract: looking for renal stones

- Ultrasound of the neck: pre-operative planning and to identify adenomas (first line)

- Nuclear imaging (e.g. sestamibi scan): for pre-operative planning and to identify adenomas (second line)

Management

Acute, severe hypercalcaemia of any cause requires urgent management in secondary care including the administration of intravenous fluids. An intravenous bisphosphonate such as pamidronate may also be indicated.8

Mild primary hyperparathyroidism may not require any management other than monitoring symptoms and complications. This includes annual tests for corrected calcium and creatinine or eGFR, as well as assessing cardiovascular and fracture risk.

Medical management

Medical management includes:1,11

- Bisphosphonates: do not affect serum calcium but do preserve bone density and therefore reduce fracture risk

- Cinacalcet (a calcium-sensing receptor agonist): reduces PTH secretion and therefore serum calcium. It is used in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism in whom surgery would not be appropriate, has been declined or has been unsuccessful

Secondary hyperparathyroidism should be managed by treating the underlying cause. Cinacalcet may be used for patients in whom this fails or who are on dialysis. Phosphate binders and calcium/vitamin D supplements may also be used, for example in chronic kidney disease.

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism may also be treated with surgical intervention (partial parathyroidectomy). Sometimes residual parathyroid tissue is reimplanted elsewhere in the body (e.g the forearm), where it is more accessible if future problems arise.

Surgical management

Curative therapy requires surgery (e.g. parathyroidectomy) and a referral can be considered for patients with confirmed primary hyperparathyroidism. NICE guidelines recommend referring for surgical management if:11

- Symptoms of hypercalcaemia such as thirst, polyuria, or constipation

- End-organ disease (renal stones, fragility fractures or osteoporosis)

- Corrected calcium level of 2.85 mmol/litre or greater

Complications of surgery include hypocalcaemia, hoarseness and cough due to damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, bleeding, infection, or failure of surgery.5

Complications

Complications of primary hyperparathyroidism include osteoporosis, renal impairment and calculi, pseudogout, pancreatitis and cardiovascular disease.1

Key points

- Hyperparathyroidism occurs when there is an excess of parathyroid hormone (PTH) being secreted from the parathyroid glands in the neck.

- Primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcaemia.

- Hyperparathyroidism often presents with mild, non-specific symptoms and may be detected incidentally.

- It is important to exclude other causes of hypercalcaemia, such as malignancy. In the first instance, a serum PTH with paired corrected calcium is the investigation of choice.

- Primary hyperparathyroidism may be treated conservatively, with surgical management or with medications such as cinacalcet

- Secondary hyperparathyroidism occurs because of conditions causing low serum calcium, often vitamin D deficiency or CKD, and is best treated with correction of the underlying cause where possible

- Tertiary hyperparathyroidism occurs when the parathyroid glands become hyperplastic following a period of secondary hyperparathyroidism and may require surgery

Reviewer

Dr Michelle Emery

Consultant in Endocrinology and Diabetes

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Wass J, Owen K. Calcium and bone metabolism. In: Oxford Handbook of Endocrinology and Diabetes. Oxford University Press 2014.

- Drake R, Vogl W, Mitchell A. Neck. In: Gray’s Anatomy for Students. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier 2014.

- Wikimedia Commons, Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands, License: [Public domain]

- Costanzo L. Endocrine physiology. In: Physiology. Elsevier 2017.

- Patient.info. Hyperparathyroidismt. Available from: [LINK]

- Mayo Clinic. Hyperparathyroidism – Symptoms and causes. Available from: [LINK]

- Khan AA, Hanley DA, Rizzoli R, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism: review and recommendations on evaluation, diagnosis, and management. A Canadian and international consensus. Osteoporos Int 2017;28. doi:10.1007/S00198-016-3716-2

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. Hypercalcaemia. Available from: [LINK]

- Saint S, Chopra V. Hypercalcemia. In: The Saint-Chopra Guide to Inpatient Medicine. Oxford University Press 2018.

- Mansoor AM. Hypercalcemia. In: Frameworks for Internal Medicine. Wolters Kluwer 2018.

- NICE. Hyperparathyroidism (primary): diagnosis, assessment and initial management. Available from: [LINK]