- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Infective endocarditis is when the heart’s inner lining (the endocardium) becomes inflamed secondary to an infection.

Infective endocarditis occurs worldwide and has, on average, around a 40% mortality rate. However, it remains a rare disease, especially in the West, with an incidence of approximately 1.7 – 6.2 cases per 100,000 patient years.1

Men are more commonly affected than women (ratio of >2:1), with higher rates seen in multimorbid patients, the elderly, those with internal cardiac devices and intravenous drug users.1,2

Aetiology

Anatomy

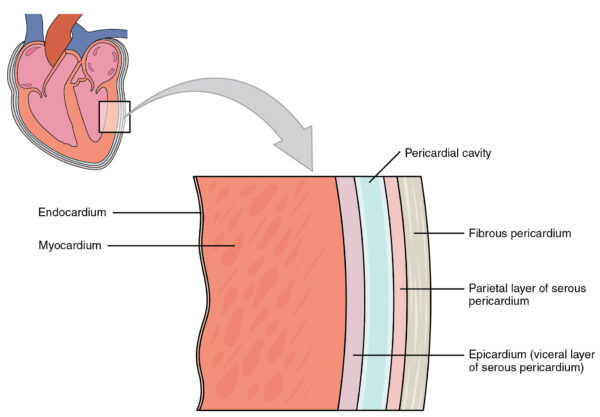

The wall of the heart is divided into three main layers:

- An outer epicardium (connective tissue and fat)

- A middle muscular myocardium

- An inner endocardium

The endocardium is the heart’s thin, smooth interior lining covering the heart valves. It comprises a specialised endothelium (similar to that in blood vessels) and connective tissue.3

Classification of endocarditis

Depending on the valve affected, endocarditis may be classified as left-sided (mitral/aortic valve) or right-sided (tricuspid/pulmonary valve). Most cases involve the left side; only 5-10% are right-sided.5

This may be further subdivided into native valve endocarditis (where the patient’s own heart valves are affected) or prosthetic valve endocarditis (affecting bioprosthetic or mechanical valve replacements).

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) makes up 20% of all endocarditis cases.6 This is the most severe form of endocarditis, and the prognosis is often poor.

Early PVE is seen within 12 months of surgery due to intraoperative contamination or spread to the valve via the blood within days or weeks of the operation. Staphylococcus aureus is most commonly associated with early PVE.

Late PVE, on the other hand, is a community-acquired infection that occurs more than 12 months post-op and is caused by similar microorganisms to those found in native valve endocarditis (streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus).

Pathophysiology

Infective endocarditis arises from three key factors occurring simultaneously:

- Transient bacteraemia

- Damage to valvular tissue

- Formation of vegetations

Pathogens must first enter the bloodstream. This can occur from many sources, including dental infections, intra-operative contamination or intravenous drug use.

Endocarditis is typically seen in patients with damaged or prosthetic heart valves, although it may occasionally occur in healthy valves.

When the valve is damaged (e.g. by trauma or the infecting organism itself), the endothelium is exposed, leading to an aggregation of platelets and fibrin at the affected site.

The circulating pathogen binds to this platelet-fibrin matrix and continues to proliferate. The pathogen is “buried” by continued deposition of platelets, fibrin and other serum molecules, thus forming what is known as a vegetation.7

This explains why removing the organism is difficult for the host immune system. In addition, the endocardium is poorly vascularised and difficult for antibiotics to penetrate, and prolonged courses of strong antibiotics are therefore required to clear the infection.7,8

These vegetations have the potential to embolise and cause further complications. Emboli resulting from left-sided endocarditis may cause cerebral infarcts (strokes) or cerebral abscesses, whereas those from right-sided endocarditis may lead to mycotic aneurysms, pulmonary infarcts or pulmonary abscesses.

Deposition of circulating immune complexes in organs such as the skin, kidneys and eyes (an example of a type 3 hypersensitivity reaction) is also seen.

Microbiology

Bacteria cause most cases of endocarditis, with Staphylococci now overtaking Streptococci as the leading pathogen.2

Staphylococcus aureus is particularly linked to endocarditis in patients with prosthetic valves, acute endocarditis and intravenous drug use.9

Table 1. Causative pathogens of infective endocarditis.

| Class of pathogen | Causative organisms |

| Gram-positive bacteria |

|

| Gram-negative bacteria |

*Haemophilus spp., Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium spp., Eikenella corrodens, Kingella kingae |

| Fungi |

|

Blood culture-negative infective endocarditis

In a significant proportion of cases (up to 31%), no causative microorganism is identified from standard blood culture methods – so-called blood culture-negative infective endocarditis (BCNIE).9

This is often due to the patient receiving antibiotic therapy before blood cultures are taken. Still, there are several important bacteria to remember, as further investigations may be required to identify them (e.g. serology).

Culture-negative bacteria may include:

- HACEK organisms

- Coxiella burnetti (Q fever)

- Chlamydia spp

- Bartonella spp (trench fever and cat-scratch disease)

- Legionella

Risk factors

Endocarditis risk factors may be divided into those related to the heart (intrinsic) and those external to the heart (extrinsic).9,10,11

Intrinsic risk factors include:

- Valvular stenosis or regurgitation: congenital or acquired

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Structural heart disease with turbulent flow (e.g. VSD, PDA): but NOT isolated ASD or fully repaired VSD or PDA

- Prosthetic heart valves: these will require replacement if infected

- Previous infection (infective endocarditis/rheumatic fever) causing structural damage

Extrinsic risk factors include:

- Intravenous drug use (right-sided endocarditis)

- Invasive vascular procedures (e.g. central lines)

- Poor oral hygiene/dental infections

Clinical features

Patients with infective endocarditis may present acutely (otherwise known as fulminant endocarditis) or subacutely over weeks to months.9,10

History

Presentation is variable, but patients may complain of systemic features of infection (such as fever, malaise, night sweats, weight loss, anorexia) and symptoms of anaemia (such as fatigue and breathlessness).

Clinical examination

All patients with suspected infective endocarditis require a thorough cardiovascular examination.

Typical clinical findings in infective endocarditis include:

- Fever

- Tachycardia

- New or changing heart murmur

- Splinter haemorrhages: nailbed petechial haemorrhages

- Osler’s nodes (tender subcutaneous nodules in the fingers) and Janeway lesions (painless erythematous macules on the palms): see Table 2

- Roth spots (boat-shaped retinal haemorrhages, pale in the centre)

- Clubbing: typically a late sign

- Mild splenomegaly

- Bi-basal lung crepitations: heart failure in severe cases

Patients may also present with clinical features from emboli (e.g. weakness from a stroke).

Table 2. Comparison between Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions.12

| Osler’s nodes | Janeway lesions |

| Painful (Osler’s Ow!) | Painless |

| Typically affects fingers/toes | Typically affects palms/soles |

| Nodules | Macules/papules |

| Purple-pink with a pale centre | Erythematous/haemorrhagic |

| Localised immune-mediated response | Septic emboli |

| Subacute endocarditis | Acute endocarditis |

| Last hours to days | Last days to weeks |

The “classical” stigmata should not be used to make the diagnosis alone as these are unreliable. Instead, diagnosis is based on the Duke criteria (see diagnosis section).

Differential diagnoses

Important differential diagnoses can be divided into autoimmune/rheumatological, infective and neoplastic.9

Autoimmune/rheumatological differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus: may present with non-infective (Libman-Sacks) endocarditis

- Antiphospholipid syndrome: thromboemboli, cardiac valve disease

- Vasculitis

- Polymyalgia rheumatica: myalgia, raised inflammatory markers

- Reactive arthritis

Infective differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Lyme disease: fever, myocarditis (rarely)

- Meningitis: fever, rash

- Tuberculosis: fever, night sweats, weight loss

Neoplastic differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Atrial myxoma: fever, new murmur (“tumour plop”, mid-diastolic rumble)

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Basic observations (vital signs): signs of infection (fever, tachycardia).

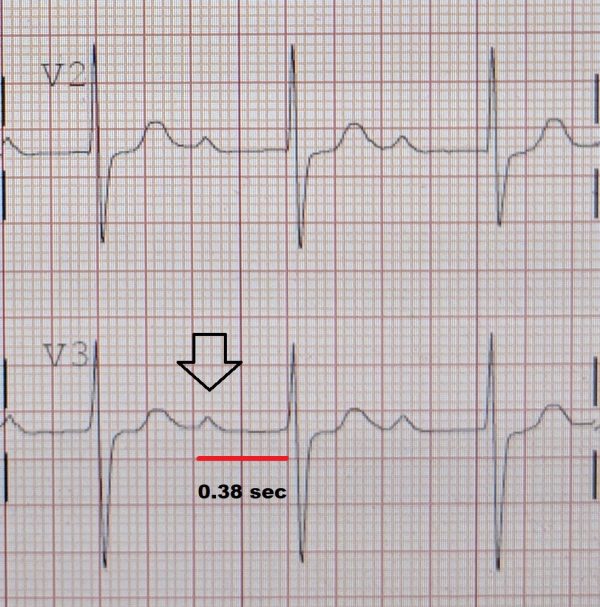

- 12-lead ECG: to exclude first degree AV block (Figure 1). This may be seen in aortic root abscesses, which are a rare complication of infective endocarditis.11

- Urine dipstick: microscopic haematuria.10

Laboratory investigations

Blood cultures

Blood cultures are a key part of the workup for endocarditis and should ideally be obtained before starting antibiotic therapy. This will reduce the number of negative cultures and help to guide appropriate treatment.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends that three sets of blood cultures (i.e. six bottles in total) be taken, at least 30 mins apart, from three separate peripheral sites. A minimum of 10 ml of blood per bottle should be collected.5

Other laboratory investigations

Other relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: to exclude anaemia (↓Hb) and check white cell count (WCC) to track the progress of the infection and response to treatment.

- CRP/ESR: inflammatory markers, used together with WCC (CRP more so). CRP may lag slightly behind WCC.

- Urea & electrolytes: baseline renal function and creatinine clearance is required if starting on nephrotoxic antibiotics such as gentamicin.

Imaging investigations

Transthoracic echocardiogram is the first-line imaging investigation in endocarditis and should be performed as soon the diagnosis of endocarditis is suspected. Note that not all vegetations are picked up on echocardiogram.10

Other relevant imaging investigations include:

- Transoesophageal echocardiogram: more invasive but provides more detail than TTE. It can aid in diagnosis where endocarditis is clinically suspected but initial TTE is negative. It may also be used to rule out local complications in patients with a positive initial TTE.5

- Chest X-ray: may be requested as part of the initial infection screen where the diagnosis is unclear. It may also be requested when heart failure (a serious complication of endocarditis) is suspected.

- CT chest: this can be helpful if a root abscess is present and if the patient is considered for surgery. When planning a re-do-sternotomy for prosthetic endocarditis, a pre-operative CT will be required as the heart structures may be stuck to the sternum.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of endocarditis is based on the Duke criteria, rather than clinical features alone.

Suspected cases may be classified into definite, possible or rejected endocarditis.5,10,18

Major criteria

Positive blood cultures

These must meet ONE of the following criteria:

- Positive for typical microorganisms on two or more separate occasions including Strep viridans, Strep bovis, HACEK group, Staph aureus, Community-acquired enterococci (in the absence of a primary focus)

- Persistently positive cultures for microorganisms consistent with IE: ≥2 positive blood cultures of blood samples drawn >12 h apart or all of 3 or a majority of ≥4 separate cultures of blood (with first and last samples drawn ≥1 h apart)

- A single positive culture for Coxiella burnetti or high antibody titre (>1:800)

Evidence of endocardial involvement

Evidence on echocardiogram of:

- Intra-cardiac vegetation (oscillating intracardiac mass)

- Abscess

- New valvular regurgitation (change in pre-existing murmurs is not included)

- New partial dehiscence of prosthetic valve

Minor criteria

Minor Duke criteria include:

- Risk factors for infective endocarditis (see risk factors section)

- Fever > 38oC

- Vascular phenomena: septic emboli, Janeway lesions, conjunctival haemorrhage, intracranial haemorrhage

- Immunological phenomena: glomerulonephritis, Osler’s nodes, Roth spots, positive rheumatoid factor

- Microbiological evidence: positive blood cultures which do not meet the major criteria

Definite endocarditis

To make a definite (i.e. confirmed) diagnosis of endocarditis, ONE of the following is required:

- Direct evidence of infective endocarditis by histology or culture of organisms (e.g. from a vegetation)

- TWO major criteria

- ONE major + THREE minor criteria

- FIVE minor criteria

Possible endocarditis

Endocarditis is possible when there are:

- ONE major and ONE minor criterion

- THREE minor criteria

In other words, there is some evidence of endocarditis but not enough to make a definite diagnosis.

Rejected endocarditis

A diagnosis of endocarditis is rejected when there is:

- A firm alternative diagnosis or

- Sustained symptom resolution after <4 days of antibiotics

Management

Medical management

The mainstay of treatment of infective endocarditis is prolonged courses of antibiotics (or antifungals if the infection is of fungal aetiology).

Antibiotics are initially given intravenously for at least two weeks before switching to oral preparations.10

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) advises that treatment should last for at least six weeks in patients with prosthetic valves and two to six weeks for native valve endocarditis.

The start of the antibiotic course is taken from the first day a negative set of blood cultures is obtained (even though antibiotics will have been given before this).5

The choice of antibiotic regimen depends on multiple factors including previous antibiotic use, the type of valve affected (native vs prosthetic), the microorganism involved and the antibiotic sensitivity of the particular organism.5

Local antimicrobial guidelines should always be followed. Close liaison with microbiology/infectious diseases, cardiology and cardiothoracics (if surgery is a possibility) is required with a discussion at the infective endocarditis multidisciplinary team meeting.

The ESC emphasises the high importance of having an established endocarditis team at each heart centre to specifically manage endocarditis.5

Surgical management

Occasionally, antibiotics alone may not be enough to treat the infection and surgery to repair or replace the valve may be required.

Every patient with prosthetic valve endocarditis should have an urgent surgical review.

Indications for surgery include:5

- Heart failure (i.e severe valve disease, pulmonary oedema or cardiogenic shock)

- Uncontrolled infection

- Prevention of embolism (large vegetations)

Prophylaxis

Patients at risk of endocarditis may have other unrelated medical conditions requiring intervention.

Currently, in the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) does not recommend using prophylactic antibiotics against endocarditis for patients underging dental procedures, or procedures affecting the gastrointestinal, genitourinary or respiratory tracts. This is also true of chlorhexidine mouthwash for dental procedures.19

However, if these patients undergo a gastrointestinal or genitourinary procedure and subsequently require antibiotics for a suspected infection, the antibiotics selected should also provide effective cover against endocarditis.

Clinicians should provide patients at risk of endocarditis with clear and consistent information about prevention, including:

- The benefits and risks of antibiotic prophylaxis and an explanation of why antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer routinely recommended

- The importance of maintaining good oral health

- Symptoms that may indicate infective endocarditis and when to seek expert advice

- The risks of undergoing invasive procedures including non-medical procedures such as body piercing or tattooing

Complications

Infective endocarditis can cause localised and systemic complications.9,18

Localised complications include:

- Valve destruction

- Heart failure (secondary to valve regurgitation)

- Arrhythmias and conduction disorders (e.g. AV block)

- Myocardial infarction

- Pericarditis

- Aortic root abscess

Systemic complications include:

- Emboli (e.g. stroke, splenic infarction)

- Immune complex deposition (e.g. glomerulonephritis)

- Septicaemia

- Death

Prognosis

While progress has been made in managing patients with endocarditis, annual mortality still remains high at around 30-40%.1,2 Recurrence may be seen between two and six percent of survivors.5

Patients who are elderly, who have multiple comorbidities and those who have prosthetic valves generally have worse outcomes, as do those with severe complications from endocarditis such as heart failure or stroke.9

Certain micro-organisms are associated with more aggressive forms of the disease and can lead to higher mortality rates (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus, non-HACEK Gram-negative bacilli, fungi).

Similarly, echocardiograms may demonstrate pathology associated with a poor prognosis, such as large vegetations, severe left-sided valve regurgitation and low left ventricular ejection fraction.

Key points

- Infective endocarditis is inflammation of the endocardium secondary to an infection

- Although rare in the West, the worldwide mortality rate is around 40%

- Consider endocarditis in anyone with pyrexia of unknown origin +/- new murmur

- First-line investigations are blood cultures (3 sets taken 30 minutes apart from 3 separate sites) and transthoracic echocardiogram

- Diagnosis is made using the Duke criteria. For a definite diagnosis, there must be direct evidence of endocarditis on histology or culture or fulfilment of TWO major criteria, or ONE major and THREE minor criteria, or FIVE minor criteria.

- Treatment is with prolonged courses of antibiotics +/- surgery

- Complications include heart failure, conduction disorders and embolic events

Reviewer

Miss Charlotte Holmes

Cardiothoracic Surgery Registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- BMJ (Beynon RP, Bahl VK, Prendergast BD). Clinical Review Infective Endocarditis. Published in 2006. Available from: [LINK]

- The Lancet (Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD). Infective Endocarditis. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- OpenStax. Heart anatomy. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- OpenStax College. Heart Wall. Licence: [CC BY 3.0]

- European Heart Journal (Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al.). ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- StatPearls [Internet] (Khalil H, Soufi S). Prosthetic valve endocarditis. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Nature (Holland TL, Baddour LM, Bayer AS, et al.) Infective endocarditis. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- The Journal of Infectious Diseases (McCormick JK, Tripp TJ, Dunny GM et al.). Formation of vegetations during infective endocarditis excludes binding of bacterial-specific host antibodies to Enterococcus faecalis. Published in 2002. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK (Tidy, C and Knott, L). Infective Endocarditis. Last edited in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Essentials of Kumar and Clark’s Clinical Medicine (Anne Ballinger), 5th edition. Infective endocarditis. Published in 2011.

- Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine (Collier, JAB), 9th edition. Published in 2014.

- StatPearls [Internet] (Parashar K, Daveluy S). Osler Nodes and Janeway Lesions. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Desherinka. Fingers with clubbing (Dedos con acropaqia). Licence: [CC BY-SA 4.0]

- Roberto J. Galindo. Osler’s Nodes (Hand). Licence: [CC BY-SA 4.0]

- Warfieldian. Janeway Lesions (Hand). Licence: [CC BY-SA 4.0]

- James Heilman. 1st Degree Heart Block. Licence: [CC BY-SA 4.0]

- BMC Nephrology (Koya D, Shibuya K, Kikkawa R, et al.). Vegetation on tricuspid valve by echocardiography. Licence: [CC BY 2.0]

- Oxford Handbook for the Foundation Programme (Raine T, Collins G, Hall C, et al.), 5th edition. Infective endocarditis. Published in 2018.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis in adults and children undergoing interventional procedures. Last updated in 2016. Available from: [LINK]