- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

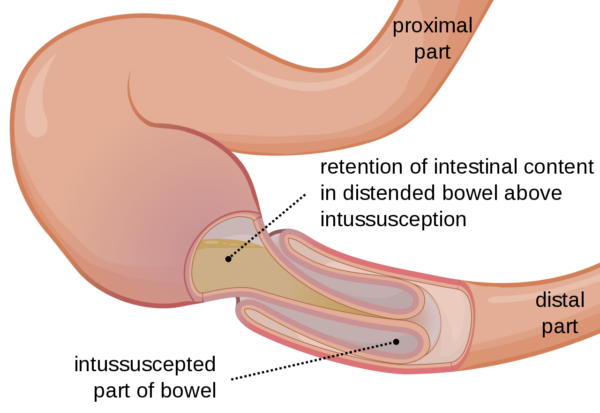

Intussusception is a paediatric surgical emergency that occurs when a section of the bowel telescopes into its neighbouring distal section, causing bowel obstruction. The most common site is the ileocaecal valve (ileocolic intussusception).1,2

If left untreated, intussusception can result in serious complications including bowel necrosis, perforation and peritonitis.

Aetiology

In most cases of intussusception, there is no clear cause. It can be associated with a preceding viral infection and may occur due to an enlarged Peyer’s patch acting as a ‘lead point’, facilitating the telescoping of the ileum through the ileocaecal valve.3

Around 10% of cases occur due to the presence of a pathological lead point. This is an abnormal area in the bowel which is caught and pulled by peristalsis, thus leading the intussusception.2

Intussusception due to a pathological lead point is more likely in patients presenting outside the typical age range or where intussusception occurs away from the ileocaecal valve.

Examples of pathological lead points and other secondary causes of intussusception include:4

- Meckel’s diverticula (and other congenital bowel defects)

- Intestinal polys

- Lymphomas and leukaemias

- Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP)

Risk factors

Intussusception most frequently occurs in children aged four to eighteen months and is slightly more common in boys.1

Clinical features

History

The typical triad of symptoms of intussusception include:2

- Intermittent, severe abdominal pain: may present as screaming episodes during which the child is inconsolable and draws their knees up to their chest. The child may appear well between episodes but will become more lethargic over time as dehydration worsens.

- Vomiting: becomes bilious in later stages when bowel obstruction occurs

- Redcurrant jelly stool: a late feature that occurs when ischaemic mucosal tissue is sloughed off and is excreted in the stool, mixed with blood and mucus (it is a rare presenting feature).

In clinical practice, only one-third of patients present with all three of these symptoms. Other symptoms may include lethargy or episodes of pain with odd posturing which may be mistaken for seizure activity.4,5

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Birth and developmental history: including antenatal scans and neonatal problems

- Systemic enquiry: to identify cases where there is an underlying secondary cause, such as HSP

Clinical examination

An ABCDE approach should be adopted in order to quickly identify the unwell, dehydrated child who requires early resuscitation. This type of systematic examination is also important to identify signs of an underlying cause of intussusception.

Observation is an important part of the initial clinical assessment. Typical findings on observing the child may include:

- Signs of dehydration, such as sunken eyes and dry lips

- Episodes of screaming +/- drawing knees up to their chest

- Lethargy or excessive sleepiness

- Rashes or other features of secondary causes

The hallmark sign of intussusception is a sausage-shaped mass palpable in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.2

Other signs on abdominal examination may include tenderness, reduced/absent bowel sounds, distension (secondary to bowel obstruction) and, in the late stages, peritonitis (secondary to perforation).2

Differential diagnoses

Due to the non-specific presentation of intussusception, there are multiple differential diagnoses to consider:1

- Constipation

- Gastroenteritis

- Malrotation volvulus

- Incarcerated hernia

- Adhesional bowel obstruction

- Testicular torsion

- Appendicitis

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Basic observations (vital signs): especially heart rate and blood pressure, which may be abnormal if the child is dehydrated and unwell

- Capillary blood gas: significant acid-base disturbances can be present in severely unwell children with intussusception

- Urinalysis: to look for evidence of a urinary tract infection, which is a cause of abdominal pain in children

- Stool sample for microscopy, culture and sensitivities: to look for evidence of gastroenteritis

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:

- Full blood count: neutrophilia may be present in later stages

- Urea & electrolytes: dehydration and vomiting may cause electrolyte disturbances

- Liver function tests: to exclude a hepatobiliary cause

- CRP: may be elevated in later stages

Imaging investigations

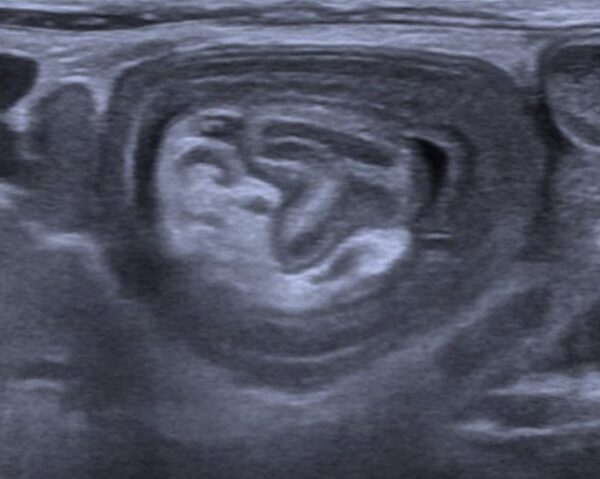

The gold-standard investigation for suspected intussusception is an abdominal ultrasound.6

This classically shows a ‘target sign’ and has a sensitivity and specificity of close to 100% (Figure 2). Ultrasound may also give important information about the likely success of subsequent reduction.3,7

An abdominal X-ray can also be performed. However, this is less sensitive and specific than ultrasound and is not commonly requested.8 Abdominal X-ray may show a typical picture of bowel obstruction, with distended proximal loops of bowel and paucity of distal bowel gas.

Management

Initial management

Prompt and adequate fluid resuscitation is vital for the management of intussusception and failure to instigate this early is one of the main causes of mortality in intussusception.6

Additional initial management should include:3

- Analgesia: this might be in the form of intravenous paracetamol or opioids

- Inserting a nasogastric tube to decompress the stomach

- Making the child nil-by-mouth

Definitive management

Non-surgical

For most cases, the first-line method to reduce intussusception is an air enema or water enema.

Enemas are successful in over 80% of cases and have around a 10% recurrence rate.9 The procedure is carried out under fluoroscopic guidance. Air is introduced to the gut via a foley catheter in the rectum under pressure to reduce the intussusception.

This approach is less likely to be successful in children who have a pathological lead-point and is contraindicated if there is evidence of shock, perforation or peritonitis.3,9

Surgical

Where non-surgical reduction is unsuccessful, or there is evidence of perforation or peritonitis, surgery is required to manually reduce the intussusception.6 This can be performed laparoscopically but is often converted to an open procedure. If this is unsuccessful, bowel resection may be required.

Complications

The main causes of mortality are late presentation, sepsis and a failure to instigate appropriate fluid resuscitation early.6

Serious complications are uncommon when intussusception is identified and treated promptly. Where there is a delay to definitive management, bowel necrosis, perforation, peritonitis and sepsis may occur.6

Key points

- Intussusception is a condition where a segment of the bowel telescopes into its distal neighbouring segment

- The cause is often unknown, however, it may follow a recent viral infection or be due to a pathological lead point

- Clinical features include severe episodic abdominal pain, vomiting, a right upper quadrant mass, dehydration and redcurrant jelly stools

- Diagnosis is readily made by the presence of a target sign on abdominal ultrasound

- Early fluid resuscitation is a key management priority

- First-line definitive management is usually with an air or water enema. Surgical reduction or bowel resection may be required if this is unsuccessful or if there are complicating features such as peritonitis or a pathological lead point.

Reviewer

Dr Cameron Kuronen-Stewart

Core Surgical Trainee

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Jain S, Haydel MJ. Child Intussusception. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available from: [LINK]

- Marsicovetere P, Ivatury SJ, White B, Holubar SD. Intestinal Intussusception: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017 Feb;30(1):30-39. Available from: [LINK]

- ID, Sugarman., VA, Lane. (2014) Intussusception. In: Max Pachl et. al. Key Clinical Topics in Paediatric Surgery. 1st JP Medical LTD.2013. Chapter 54 (p181-184).

- Patient.info. Intussusception in Children. Updated 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Park IK, Cho MJ. Clinical Characteristics According to Age and Duration of Symptoms to Be Considered for Rapid Diagnosis of Paediatric Intussusception. Front Pediatr. 2021; 9:651297. Available from: [LINK]

- Mendiratta P, Yadav A, Borse N. Paediatric small-bowel intussusception on ultrasound – a case report with differentiating features from the ileocolic subtype. J Ultrason. 2021; 21(84): 70-73. Available from: [LINK]

- Henderson AA, Anupindi SA, Servaes S, Markowitz RI, Aronson PL, McLoughlin RJ et al. Comparison of 2-view abdominal radiographs with ultrasound in children with suspected intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013; 29(2):145-50. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Intussusception. Available from: [LINK]

- Daneman A, Navarro O. Intussusception Part 2: An update on the evolution of management. Paediatr Radiol. 2004. 34;97-108. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

- Figure 1. Orem. Drawing of intussusception. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 2. Benutzer:Kalumet. Sonographic image of an intestine-invagination. License: [CC BY-SA]