- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Laryngomalacia is a congenital abnormality of the larynx cartilage which causes intermittent airway obstruction (laryngo: relating to the larynx, malacia: abnormal softening of a tissue).

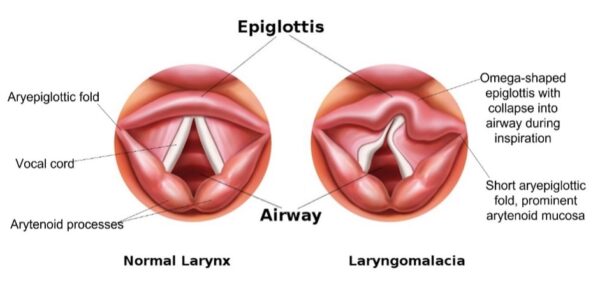

Patients usually present with inspiratory stridor. In laryngomalacia, stridor is caused by the collapse of the supraglottic structures (e.g. epiglottis, arytenoid processes) into the airway.

Laryngomalacia is the most common laryngeal anomaly and congenital cause of stridor in infants.1

Patients usually present in infancy, with inspiratory stridor commencing within the first two weeks of life. Symptoms tend to be at their worst at six to eight months of age before gradual improvement. Most children are free of symptoms by 18-24 months of age.1

Aetiology

The aetiology of laryngomalacia is not fully understood, but there are several proposed theories.

The anatomical theory suggests that laryngomalacia is due to laryngeal anatomical abnormality, particularly short aryepiglottic folds, prominent arytenoid mucosa, and a curled ‘omega-shaped’ (Ω) epiglottis. It has also been suggested that flaccidity in the laryngeal cartilage may contribute.

Alternatively, neuromuscular incoordination may contribute to suboptimal laryngeal tone. Additionally, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is implicated in up to 80% of cases.2

Poiseullie’s law

Poiseullie’s law is a useful concept for understanding the pathophysiology of paediatric airway obstruction. The law states that the resistance of a tube is inversely proportional to the fourth power of its radius.

In clinical terms (i.e. air being inspired through the larynx), any change in airway radius significantly influences airway resistance.5

The radius of the infantile larynx is already very small, so any further narrowing may precipitate life-threatening airway compromise due to massively increased airway resistance. Conversely, as the infant grows, the airway radius increases and resistance significantly decreases. This is one of the mechanisms by which children outgrow laryngomalacia.

Risk factors

Risk factors for laryngomalacia include:1

- Laryngeal anatomical abnormality

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD): reported in 50-100% of patients with laryngomalacia

- Neurological abnormality: in up to 20% of patients

- Male sex: 2:1 male:female incidence ratio

- Genetic syndromic disorder: more common in Down’s syndrome and patients with congenital cardiac disease

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of laryngomalacia include:1

- Stridor worsened by crying, exertion, lying supine, and feeding

- Onset of stridor within 2 weeks of birth

- A natural progression of symptom severity, peaking at 6-8 months and with the resolution of symptoms by 2 years of age (70% resolution by 12 months)

- Feeding difficulties (increased respiratory effort, choking episodes) leading to poor weight gain in more severe cases

A collateral history from the parent or guardian is essential. Reviewing the personal child health record (known as the “red book” in the UK) is a useful way to objectively assess weight gain and development.

Clinical examination

Examination of all unwell patients should follow the ABCDE approach. For patients with laryngomalacia, particular attention should be paid to signs of increased work of breathing and respiratory distress.

Typical clinical findings in laryngomalacia include:

- Stridor

- Nasal flaring

- Tracheal tug

- Intercostal and subcostal recession

- Abdominal respiration

- Patients with laryngomalacia usually have a normal cry

Differential diagnoses

The absence of typical features of laryngomalacia would favour an alternative diagnosis. Differential diagnoses to consider include:1,3

- Vocal fold palsy

- Subglottic stenosis

- Laryngeal web

- Laryngeal cleft

- Laryngeal cyst

- Subglottic haemangioma

- Tracheomalacia

- Vascular ring

- Foreign body aspiration

Investigations

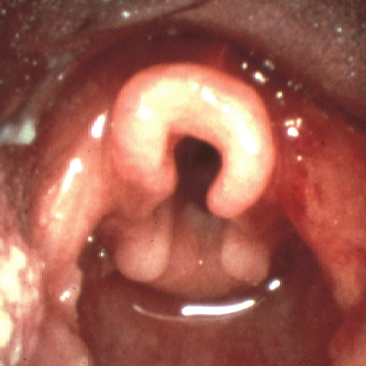

Flexible nasendoscopy (FNE) is the key diagnostic investigation. It is used to assess for typical laryngeal anatomical features and other risk factors (e.g. mucosal inflammation associated with GORD). FNE is performed by ENT doctors with the patient awake and breathing spontaneously. If the history is atypical, the infant may require additional assessment under a general anaesthetic.

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:

- Basic observations (including paediatric early warning score): oxygen saturations and respiratory rate are particularly relevant

Laboratory investigations

There are no laboratory tests which can diagnose laryngomalacia. However, haematological tests (e.g. blood gas, full blood count, C-reactive protein) or microbiological sampling of sputum may be taken if there is suspicion of underlying or exacerbating infection.

Imaging

A chest X-ray may provide evidence of other airway pathology, concurrent lower respiratory tract infection, or foreign body aspiration.

Other investigations

In some cases, laryngomalacia may be coexistent with other abnormalities of the airway, and further investigations are required.

Other relevant investigations may include:

- Microlaryngobronchosopy (MLB): a diagnostic procedure performed under general anaesthetic, whereby a rigid endoscope is passed through the mouth to visualise the trachea, main bronchi and the structures of the larynx.

- Polysomnography (sleep study): used to characterise associated obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA). Oximetry and other data are recorded during sleep. This is useful for making decisions about complex patients with multiple medical problems. It can be a difficult test to interpret in infants.

Diagnosis

Laryngomalacia is a clinical diagnosis, based primarily on flexible nasendoscopy (FNE) findings.

Positive diagnostic findings on FNE include short aryepiglottic folds, prominent arytenoid mucosa, and a curled, omega-shaped epiglottis. This results in the dynamic collapse of the supraglottic tissues on inspiration, causing intermittent airway obstruction.

Management

Mild laryngomalacia is often managed by paediatricians, with ENT specialist involvement required only in more severe cases.

Conservative management

In milder cases, patients thrive despite audible stridor and endoscopic features of laryngomalacia. Parents can be reassured of the high likelihood that this will spontaneously resolve with no long-term issues. For these children, observation with close monitoring of growth and development is the best strategy.

Medical management

Medical management is indicated in moderate to severe disease, characterised by increased work of breathing, and feeding difficulties leading to weight loss or inadequate weight gain.

Options for medical management include: 1

- Feed thickener (e.g. Carobel) is often helpful in reducing aspiration and regurgitation of milk

- Anti-reflux medication, like proton-pump inhibitors (e.g. omeprazole) or H2-receptor antagonists (e.g. famotidine), are commonly used to reduce inflammation of the supraglottis which can contribute to irritation around the airway

- Steroids (e.g. dexamethasone) are used in patients with acute respiratory distress to reduce laryngeal swelling and increase airway patency. Steroids will work in many cases of airway distress and not just in laryngomalacia.

Surgical management

Surgical techniques can correct anatomical abnormalities in patients with severe disease (10-15% of patients with laryngomalacia).1

These patients present with significant airway compromise or failure to thrive, caused by severe obstructive breathing patterns and feeding difficulties. The signs of increased effort of breathing are the most clinically relevant. Dysphagia, apnoea, hypoxia, and hypercapnia are other factors which indicate severe disease.

Options for surgical management include:

- Supraglottoplasty modifies the supraglottis by dividing or excising the aryepiglottic folds. This is the first-line surgical therapy. Tissue from the lateral portion of the arytenoids can also be removed if arytenoid prolapse is seen and the condition is severe.

- Tracheostomy is a secondary surgical option reserved for patients with other comorbidities which would limit the effectiveness of supraglottoplasty.

In very severe cases of GORD, Nissen fundoplication may be considered. This is a surgical procedure to reinforce the gastro-oesophageal sphincter and reduce acid reflux.

Complications

Complications of laryngomalacia include:

- Life-threatening airway obstruction (occurs very rarely and mostly in cases with other co-morbidities, like infection or congenital abnormality)

- Failure to thrive

- Failure to gain weight, dropping centiles on the growth chart

- Developmental delay

- Worsening of GORD (laryngomalacia both exacerbates and is exacerbated by acid reflux)

Complications of surgery for laryngomalacia include:6

- Granuloma formation

- Worsened aspiration

- Supraglottic stenosis

- The tracheostomy-related mortality rate is about 2%

Key points

- Laryngomalacia is a congenital abnormality of the larynx cartilage which causes intermittent airway obstruction

- The majority of the patients with laryngomalacia outgrow the condition without the need for surgical intervention

- Diagnosis is based on awake flexible nasendoscopy (FNE)

- Severe laryngomalacia is characterised by respiratory distress, apnoea, and failure to thrive

- Supraglottoplasty is the surgical intervention of choice for severe cases

- Laryngomalacia may present as part of a wider group of congenital abnormalities which require thorough workup and multidisciplinary input; these cases are more complex to manage

Reviewer

Miss Tash Kunanandam

Consultant Paediatric Otolaryngologist

Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- BMJ Best Practice. Published in 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Thompson DM. Abnormal sensorimotor integrative function of the larynx in congenital laryngomalacia: a new theory of etiology. The Laryngoscope. 2007;117(S114):1-33.

- Klinginsmith M, Goldman J / StatPearls. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Laryngomalacia. License: [CC BY]

- Doctormichael. Laryngomalacia. License: [Public domain]

- Bruce IA, Rothera MP. Upper airway obstruction in children. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2009;19:88-99.

- Cochrane LA, Bailey CM. Surgical aspects of tracheostomy in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2006 Sep;7(3):169-74.