- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

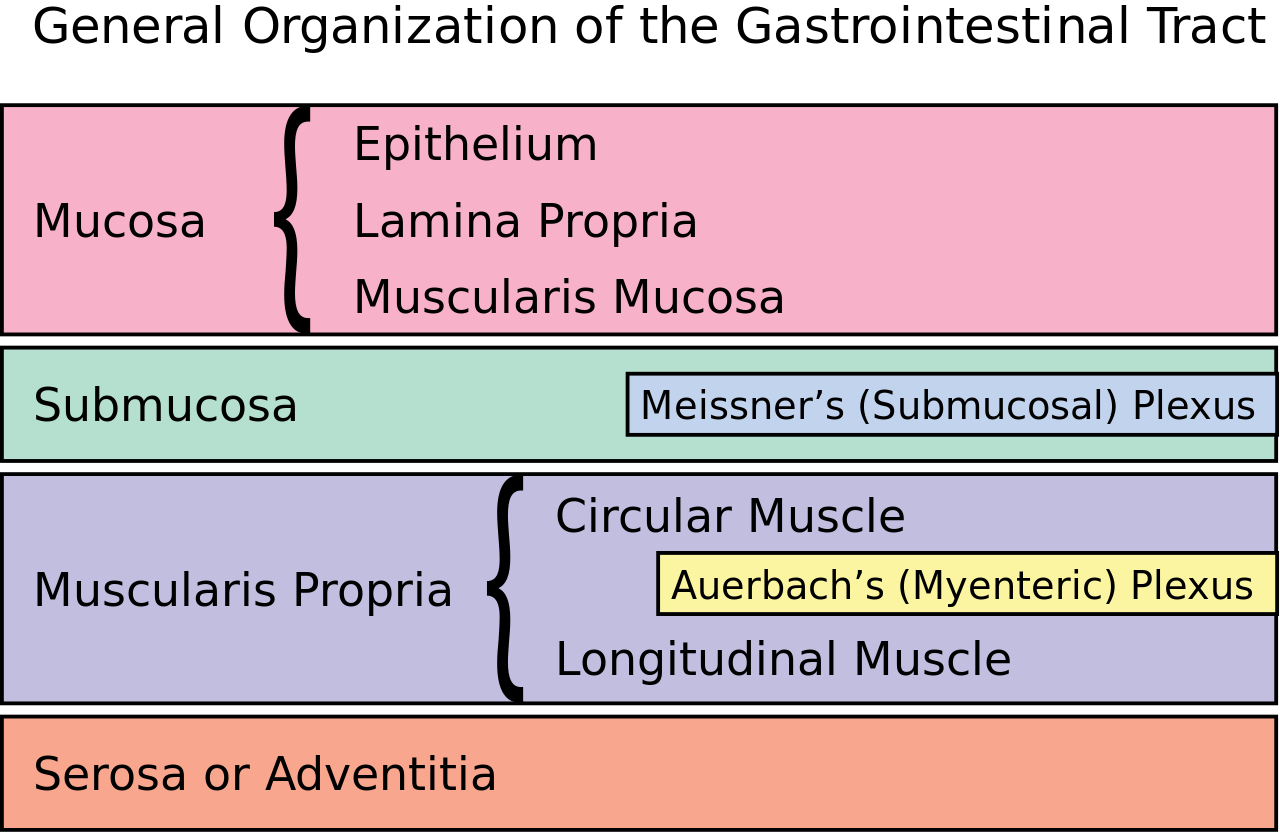

There are four highly-specialised layers in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. The layers differ over the length of the gastrointestinal tract, each having a different role.

To understand the function of the layers, it is important to remember the key functions of the gastrointestinal tract:

- Digestion and absorption of nutrients

- Excretion of digestion waste products

Layers of the gastrointestinal tract

The four layers of the gastrointestinal tract, from the lumen of the tract outwards are:1,2

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscularis propria

- Serosa or adventitia

Mucosa

The mucosa forms the innermost layer of the tract. It encases the lumen and comes into direct contact with chyme (digested food).1,2

There are three layers to the mucosa:1,2,3

- Epithelium: the innermost layer, forming a thin membrane where the majority of digestion, absorption and secretion occurs

- Lamina propria: a layer of connective tissue that lies within the mucosa, providing vascularisation and lymphoid drainage to the epithelium. The nutrients absorbed pass into the capillaries in this layer.1,2

- Muscularis mucosae: a very thin double-layer of smooth muscle that allows for local peristalsis and catastalsis of the tract

Submucosa

The submucosa is a layer of loose connective tissue, containing larger blood vessels, nerves, mucous-secreting glands and nerves.3

The submucosal and enteric nervous plexi are located in this layer, bordering the surface of the inner muscularis layer.3

Muscularis propria

The muscularis propria consists of two muscle layers – the inner layer and the outer layer.1,2

The muscle within the inner layer is arranged in a circular fashion, whilst the outer layer is arranged in a lengthwise or longitudinal fashion. In the stomach, there is a third obliquely arranged layer.4

Between the inner layer and the outer layer, the myenteric plexus is present. The myenteric plexus, in conjunction with the two layers of muscle, allows for peristalsis to occur.1,2,3

The muscular layer differs in thickness along the tract:4

- It is thicker in the large intestines as increased force is required to propel faecal matter

- It is thicker in the pylorus of the stomach to form the pyloric sphincter, which allows for the controlled release of chyme into the small intestine

- It is thinner in the small intestine as chyme is more liquid and requires less peristaltic force

Serosa or adventitia

The outermost layer of the gastrointestinal tract is either serosa or adventitia and consists of several layers of connective tissue.1,2

Serosa covers intraperitoneal structures and is continuous with the parietal peritoneum. It is thin and consists of a double wall of simple squamous epithelium.1,2

Adventitia covers retroperitoneal structures. It is made of fibrous connective tissue and fixes structures in place.1,2

Serosa and adventitia both contain blood vessels, nerves and lymphatics.

Histology of the gastrointestinal tract

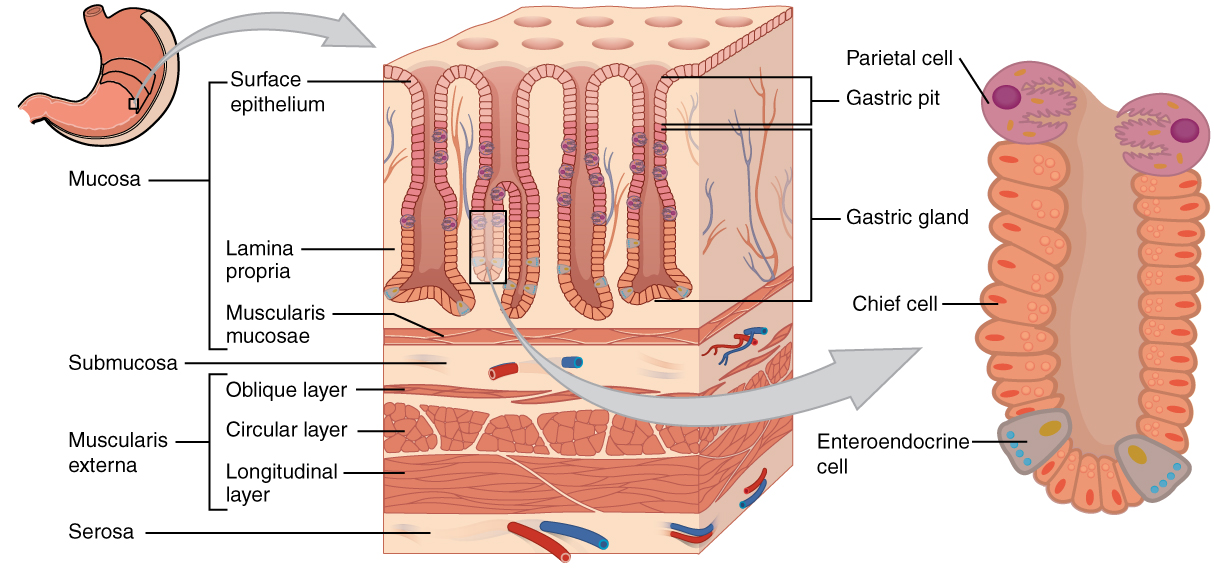

Stomach

Mucosa

The stomach mucosa consists of simple columnar epithelium with deep gastric pits that connect to the glands of the stomach lining. The glands of the stomach secrete mucous and digestive enzymes. Due to the harsh acidic conditions of the stomach, the mucosa is always covered by a thick layer of mucous, secreted by the columnar epithelium and glands.1,2,3

Submucosa

The submucosa of the stomach is thick to ensure that it is flexible and durable.2,4

Muscularis propria

The muscular layer in the stomach is uniquely three-layered (longitudinal, circular and oblique). The function of these layers is to mix and break-down food into chyme.1,2

Serosa

The majority of the stomach is intraperitoneal and needs to be able to move freely, and thus has a serosa consisting of simple squamous epithelium (mesothelium) and a thin layer of connective tissue. The pylorus of the stomach is retroperitoneal and therefore has a fibrous adventitia fixing it in place.1,2,3,4

Small intestine

Mucosa

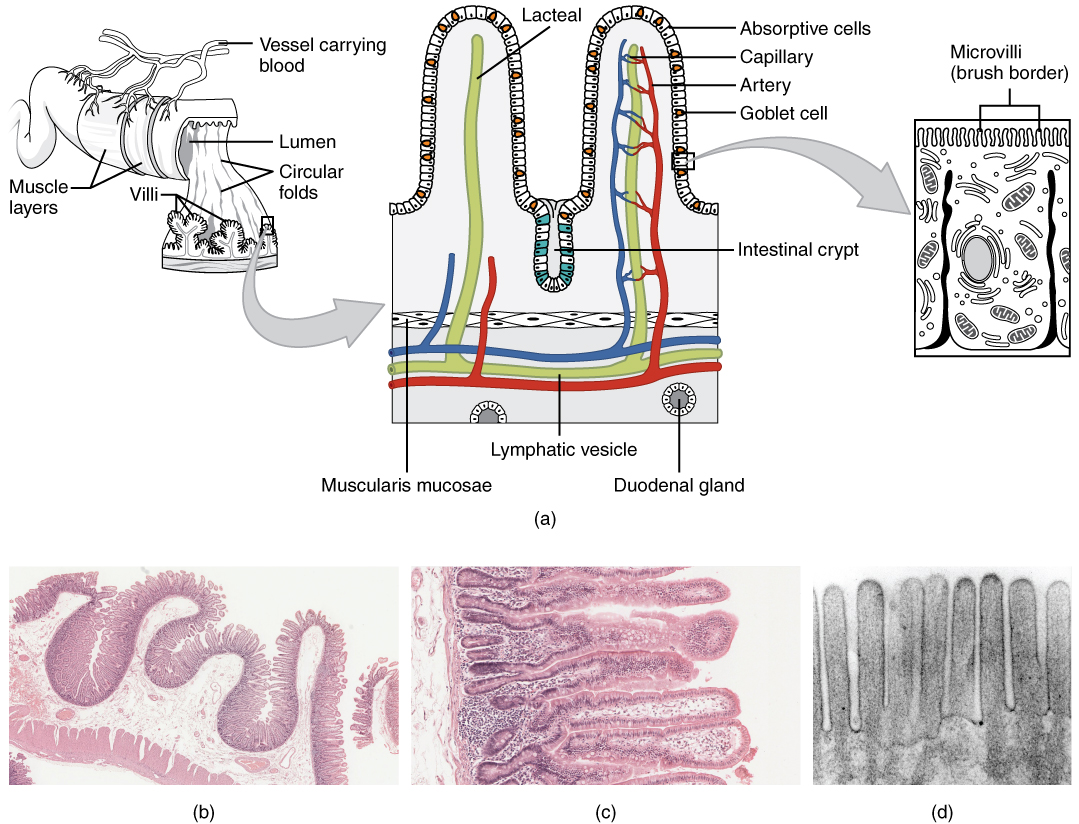

The epithelium consists of simple columnar cells with absorptive functions. The mucosa is highly folded, with numerous tiny projections known as villi. Villi are covered in absorptive cells with micro-projections from their cellular membrane known as microvilli. The villi and microvilli form the brush border, dramatically increasing the surface area and the absorptive function of the small intestines.1,2,3,4

Goblet cells (which secrete mucin), neuroendocrine Paneth Cells and crypts of Lieberkühn are also present in the mucosa.1,3

In the lamina propria of the ileum, lymphoid follicles known as Peyer’s patches are present.3,4

Submucosa

The submucosa is thinner in the small intestine and contains the neurovascular and lymphatic supply. In the duodenum, Brunner’s glands are present, which secrete alkaline-rich fluid to neutralise the acidic chyme from the stomach.1,2,3,4

Muscularis propria

There are two layers in the small intestines (longitudinal and circular) which act to maintain peristalsis.1,2

Serosa

Like the stomach, the majority of the small intestine is intraperitoneal, meaning it has a thin layer of serosa which secretes a serous fluid. This fluid reduces the friction from the movement of the muscularis propria layer. The first section of the duodenum is retroperitoneal and has adventitia.1,2,3

Large intestine

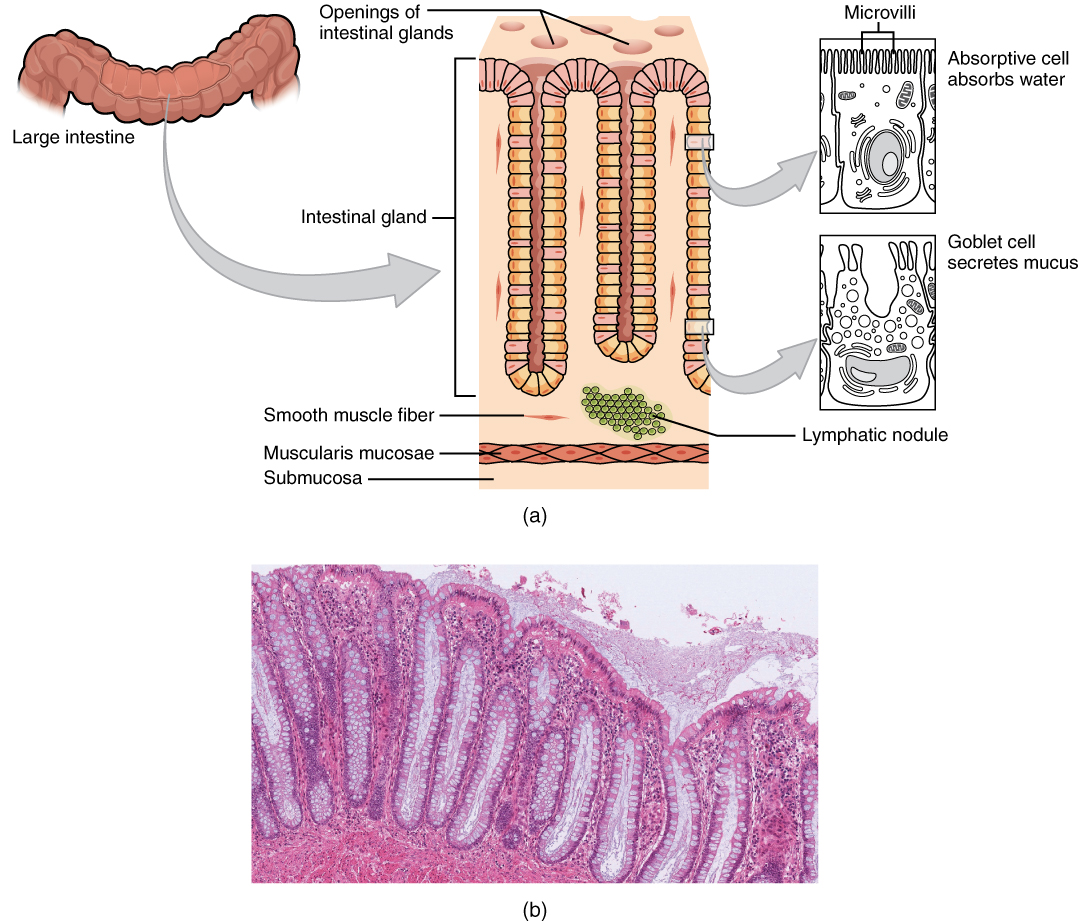

Mucosa

The colonic mucosa is lined with simple columnar epithelium, which has long microvilli. These villi have a layer of mucous that aids in the movement of faeces through the colon. Compared to the small intestine, there are no villi, but large numbers of crypts of Lieberkuhn and goblet cells. The lamina propia has large amounts of immune cells such as macrophages.1,2,3,4

Submucosa

The submucosa is thicker than the small intestines, which have large quantities of blood vessels, lymphatics and fat tissue.1

Muscularis propria

The large intestine has a larger diameter than the small intestine. The longitudinal layer is found in the three strap-like bands called taeniae coli. The inner circular layer surrounds the submucosa as with the small intestine.1,2,3

Serosa

Parts of the colon have serosa, and parts have adventitia, depending on if they are intra or retroperitoneal. The caecum, appendix, transverse colon, sigmoid colon and rectum have serosa, which consists of simple squamous epithelium that secretes fluid to reduce friction.

In contrast, the ascending and descending colons and anal canals have adventitia, which is more fibrous than serosa and fixes these organs in place.1,2

Clinical relevance: Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is confined to the large bowel and affects only the mucosal layer. Key symptoms include unexplained abdominal pain and haematochezia (diarrhoea mixed with blood) and systemic features such as anaemia, weight loss and fevers.

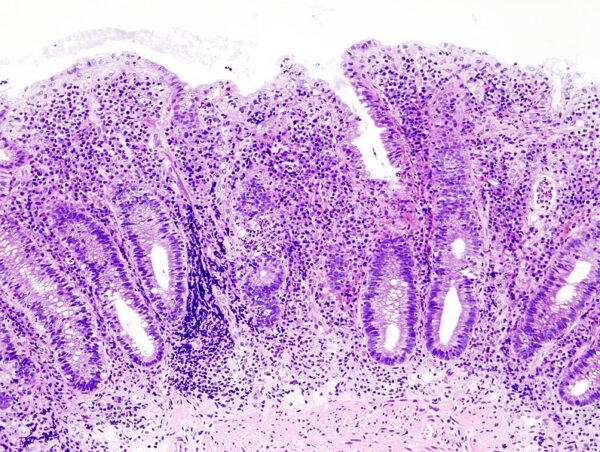

The diagnosis of UC requires a colonoscopy and biopsy. Histological findings of UC include crypt architecture loss, crypt abscesses and lymphocytic invasion of the mucosa.

In contrast, Crohn’s disease can occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract, from mouth to anus. Crohn’s disease causes transmural inflammation. Key symptoms include abdominal pain and distension, fever, weight loss, and diarrhoea (which may be bloody if the colon is affected).

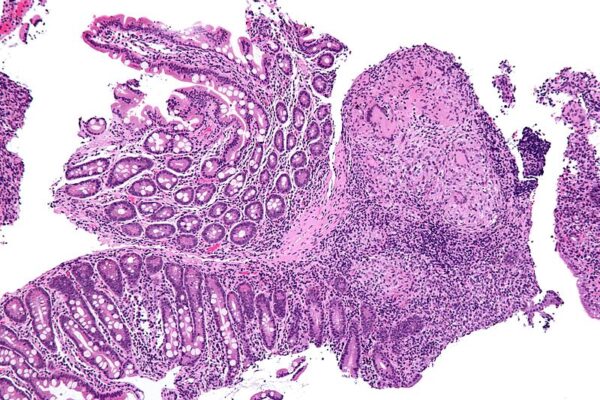

The diagnosis of Crohn’s disease is via endoscopic investigation and biopsy. Findings may include a patchy cobblestone appearance to the bowel, with areas of healthy tissue between lesions (“skip lesions“). Histological features include non-caseating granulomas, neutrophilic invasion of crypts, chronic architectural changes from inflammation and plasma cell infiltration through the lamina propria.

Key points

- There are four layers to the gastrointestinal tract: the mucosa, the submucosa, the muscularis propria and either serosa or adventitia

- Organs that are intraperitoneal and move freely have serosa, whereas fixed structures that are retroperitoneal have adventitia

- The four layers have different characteristics throughout the tract in-line with the function of each section

References

Text references

- Kumar, V., Abbas, A.K., Fausto, N. and Aster, J.C., 2021. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, professional edition e-book. Elsevier health sciences.

- Mescher, A.L., 2013. Junqueira’s Basic Histology. New York City. Junqueira’s basic histology, pp.289-322.

- Young, B., Woodford, P. and O’Dowd, G., 2013. Wheater’s functional histology E-Book: a text and colour atlas. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Mulroney, S. and Myers, A., 2015. Netter’s Essential Histology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Image references

- Figure 1. Rehua. GI Organization. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 2. OpenStax College. Histology of the stomach. License: [CC BY]

- Figure 3. OpenStax College. Histology of the small intestine. License: [CC BY]

- Figure 4. OpenStax College. Histology of the large intestine. License: [CC BY]

- Figure 5: KGH. Histopathological image of the active stage of ulcerative colitis. Endoscopic biopsy. Hematoxylin & eosin stain. License: [CC BY-SA]

- Figure 6: Nephron. Intermediate magnification micrograph of Crohn’s disease. Biopsy of duodenum. H&E stain. License: [CC BY-SA]