- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

As a clinician, you will be expected to make a diagnosis many times a day, so you must understand the diagnostic process and the factors limiting your ability to establish the correct diagnosis.

Over the past decade, several studies have shown uncertainty over the diagnosis in about half of all emergency medicine and primary care consultations.

An incorrect diagnosis is made in around 1 in 15 consultations. This leads to serious harm to patients in 0.1% of consultations in primary care and 0.3% of consultations in the emergency department.

As a result, the World Health Organisation has highlighted the need for medical students to learn about the causes of incorrect diagnoses and what clinicians can do to mitigate the risk of patient harm from these events.

This article will help you to understand how a diagnosis is made and what can cause a diagnosis to be uncertain or incorrect.

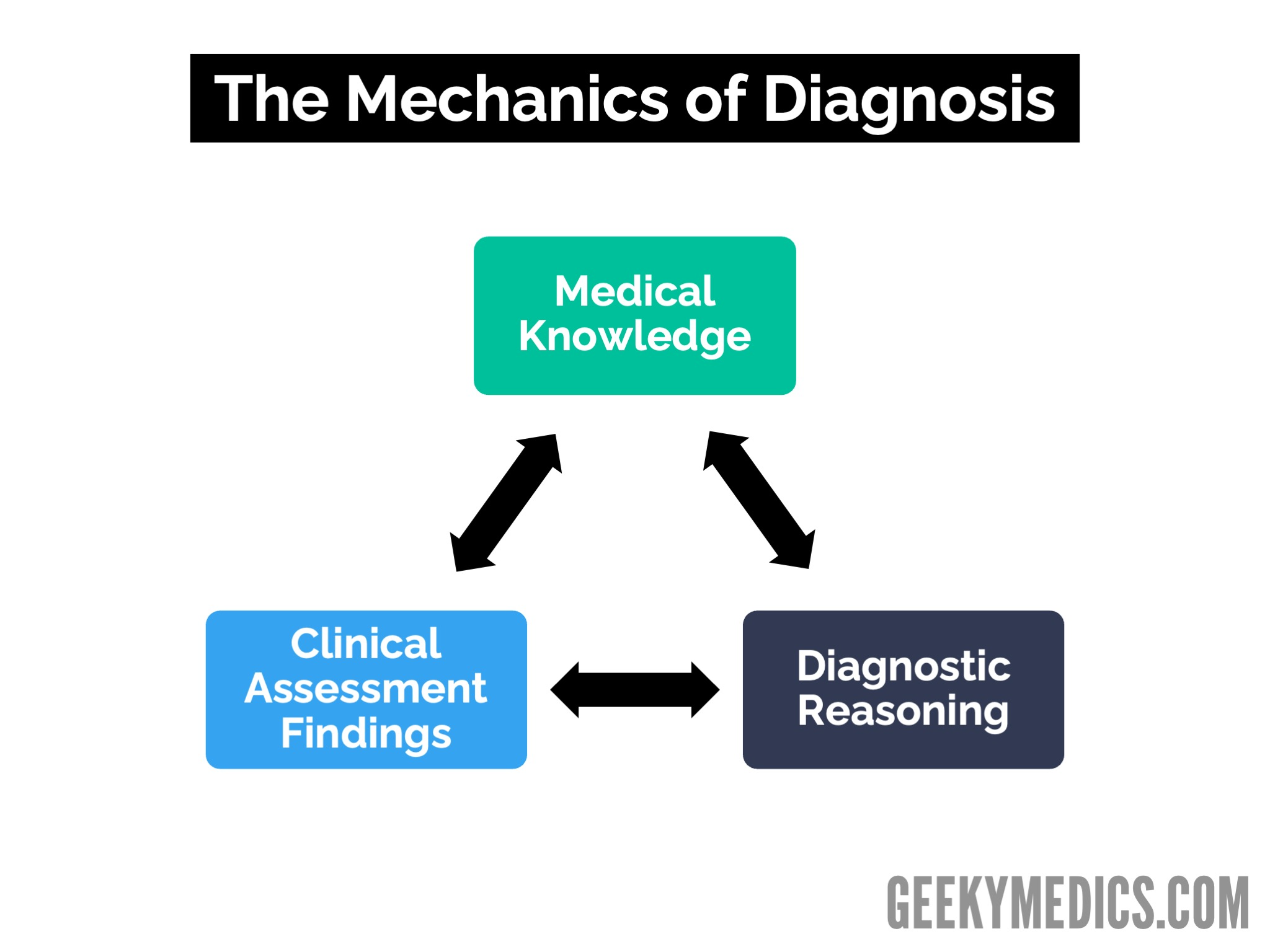

The mechanics of making a diagnosis

Making a diagnosis involves comparing what you know about the causes of a symptom and the diagnostic criteria for each cause to what you find during your clinical assessment of the patient through the application of diagnostic reasoning.

This is known as the mechanics of diagnosis (Figure 1). Diagnostic uncertainty and incorrect diagnoses are often the results of limitations and imperfections in the diagnostic process, so understanding this process is fundamental to understanding why adverse diagnostic events (ADEs) occur during consultations.

Medical knowledge

You cannot diagnose what you do not know!

Making a diagnosis involves comparing what you know to what you find, emphasising the importance of knowing the causes of a symptom and how you diagnose each cause.

An incorrect diagnosis can result from not having learned the cause of a particular symptom and how it is diagnosed, not retaining this knowledge, or not recalling the information during the consultation.

This highlights the importance of coming to the consultation with the medical knowledge required to establish the correct diagnosis and not practicing outside your area of knowledge. It also exposes limitations and imperfections in the diagnostic process because medical knowledge is vast. Some causes of a particular symptom may be uncommon and only encountered once in a medical career.

In addition, consultations are complex and consultation times are short. As a result, there will always be the potential for an incorrect diagnosis because we have not learned or retained a key piece of medical knowledge.

Clinical assessment

If you don’t find it, you won’t diagnose it!

A clinical assessment aims to gather the information you need to establish the correct diagnosis.

There is a link between medical knowledge, diagnostic reasoning and clinical assessment – unless you know what to check for, you won’t check for it.

Example

If you did not know that there are gynaecological or vascular causes of abdominal pain, you would not check for these when assessing a patient and not perform a gynaecological or vascular assessment.

As a result, an ectopic pregnancy or a dissecting abdominal aortic aneurysm might be misdiagnosed.

This also emphasises the importance of learning how to perform the psychomotor skills of clinical assessment correctly because an incorrectly performed clinical assessment may result in a key piece of information not being gathered or a false negative or false positive result being fed into the diagnostic process, with the potential for this to result in an incorrect diagnosis being made.

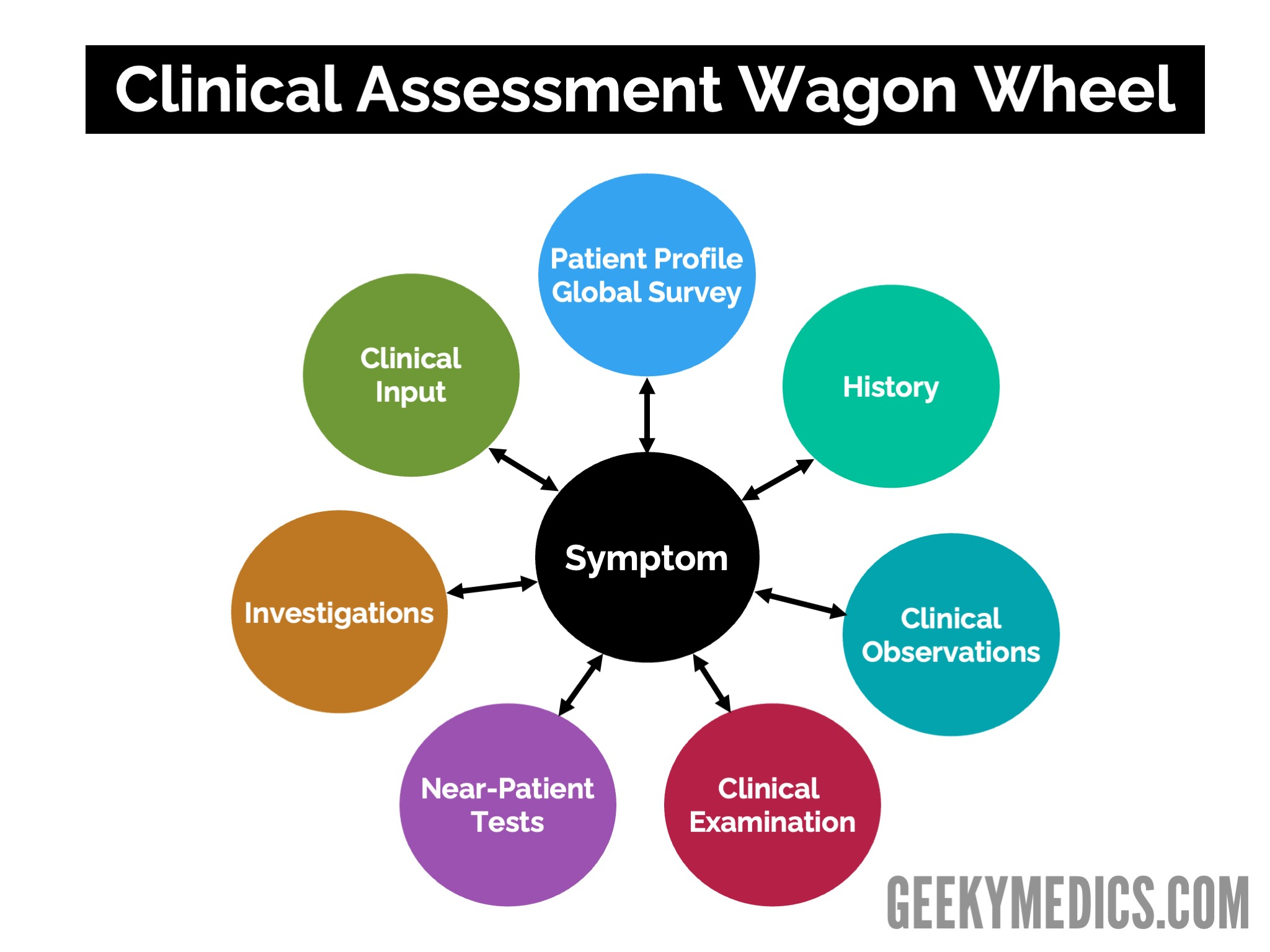

This is why developing a systematic approach to clinical assessment is essential. Figure 2 shows a model of assessment that can remind you of the components of clinical assessment and the need to adopt a systematic approach when assessing patients.

Interpretation of clinical findings

Clinical assessment is not just about the gathering of information. It is also about interpreting that information within the context of the patient, their symptoms, all of the clinical assessment findings and the sensitivity, specificity and reliability of the information gathered.

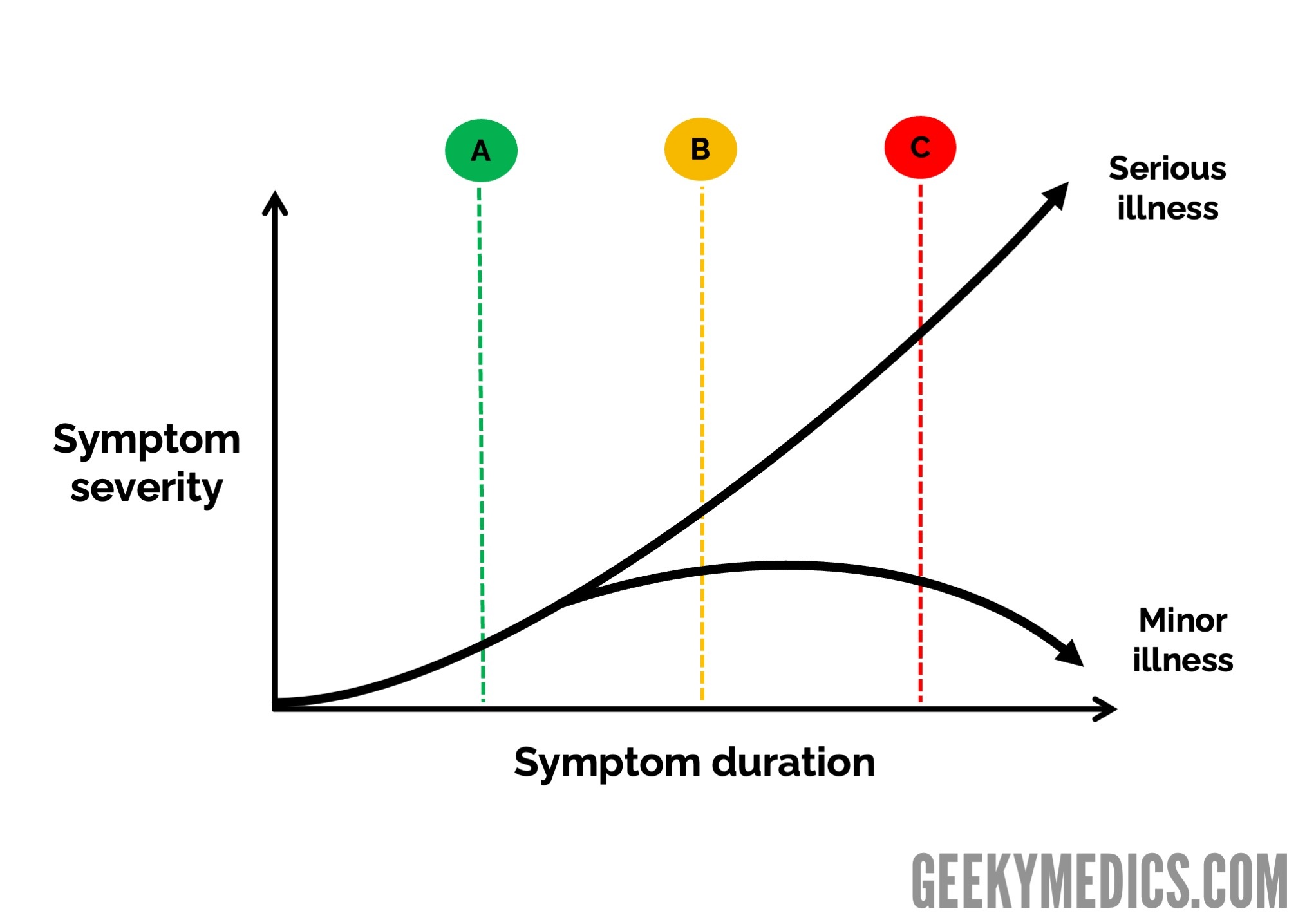

Incorrectly interpreting a finding can lead to an incorrect diagnosis being made. It is also important to appreciate that your diagnosis is based on what you find during your assessment. Since illness is a dynamic process, where illness develops over time, this would mean that the clinical assessment findings would change over time, as a result of which the diagnosis could change over time.

Therefore, if a patient presented in the early stages of a serious illness before the diagnostic findings for that illness had developed, they might be diagnosed as having a minor illness.

This is shown in Figure 3, where you can see that it is impossible to distinguish a serious illness from a minor illness at point A in time. At point B, some findings indicate that a serious illness or complication is developing, but the classic findings will only be present at point C. This creates the potential for diagnostic uncertainty and incorrect diagnoses during consultations.

Diagnostic reasoning

Your diagnosis depends on your ability to reason correctly!

Reasoning is a complex process, and it is worth learning about applied diagnostic reasoning to help you understand how you reason and what can interfere with the reasoning process and lead to an incorrect diagnosis.

Dual-process reasoning involves either:

- A rapid, intuitive form of reasoning based on pattern recognition and our previous experience of presentations of illness

- A slower, more analytical form of reasoning based on weighing up the evidence

Both processes have advantages and disadvantages; it is important to balance them when diagnosing. Faulty heuristics (shortcuts) and cognitive biases can affect how we reason. Human factors, such as tiredness, stress, illness and mood disorders and distractions in the workplace, can also affect how we reason within a consultation.

Improving your diagnostic skills

As you progress through your medical studies, there is much that you can do to help you to improve your diagnostic accuracy and reduce diagnostic risk in your consultations. Developing a patient safety-focused approach to consulting now will help prepare you for safer practice later.

Medical knowledge

During each attachment, make sure that you learn about the symptoms patients present with and the causes of those symptoms.

You can use the mnemonic SAFER to bring a patient safety focus to this.

SAFER mnemonic

- Serious (must-not-miss) causes

- Alternative (must-always-consider) causes

- Findings that do not fit with a minor illness or do fit with a serious illness

- Early & atypical presentations

- Red & amber flag findings

Ask clinicians about the causes that you “must-not-miss” and “must-always-consider” in someone presenting with that symptom. In hospital settings, such as clinics and wards, you will encounter patients later in their illness who are likely to have what is known as a “classical” or “typical” presentation of that condition.

In contrast, in the emergency department or in primary care, patients are more likely to present with early or atypical patterns. Try and learn not just about the typical presentations but also the early and atypical presentations, especially if you are considering a career in emergency medicine or primary care. Remember, you can’t diagnose what you don’t know!

Clinical assessment

Make sure that you develop a systematic approach to how you gather information from and about the patient.

Use an information-gathering system, such as the wagon wheel, as well as mnemonics and checklists. This will help remind you of the key information that needs to be gathered and how to gather it.

Practice your psychomotor skills as much as possible and learn to distinguish normal findings from abnormal findings by examining as many patients as possible. Learn about the sensitivity, specificity and reliability of each component of clinical assessment and how to interpret the findings correctly.

Diagnostic reasoning

Ensure you understand what diagnostic reasoning is, how to perform reasoning correctly and the factors that can cause you to reason incorrectly. Reflect on how you reason in other areas of your life and how this might impact your reasoning in medicine. Do you jump to conclusions or overthink things?

When you feel unwell or stressed, consider how this might affect you when diagnosing. Doing this will help you become self-aware of when you need to consider employing protective measures to protect you and your patients from incorrect diagnoses, such as checking your diagnoses with a colleague or reviewing complex cases when you feel better.

Developing good patient safety attitudes and behaviours is important in medicine. There are strategies and interventions you can learn now that will stand you in good stead when you are a clinician, such as giving safety-netting advice to patients and creating diagnostic plans.

Summary

In this article, we have discussed that a diagnosis is made by comparing what we find during our patient assessment to what we know about the causes of a symptom and how each cause is diagnosed through the application of diagnostic reasoning.

This establishes the fundamental principle that our ability to establish the correct diagnosis is a function of us coming to the consultation with the correct medical knowledge and recalling that knowledge correctly during the consultation, gathering the correct information from and about the patient and processing that information; and performing diagnostic reasoning correctly.

However, each of the components of diagnosis is subject to limitations and imperfections, which can lead to a diagnosis being uncertain or incorrect. Above all else, it is important to understand that in many cases, an uncertain or inaccurate diagnosis is not related to the clinicians’ competence but to limitations and imperfections in the diagnostic process.

Understanding these limitations and imperfections and adopting patient safety attitudes, behaviours, strategies and interventions can help us to become safer clinicians.

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Silverston, P. Teaching Safe Consulting. Student BMJ 2012. 20: e7791

- Silverston, P. Diagnosis: Uncertain. Student BMJ 2014. 22: g1674

- Silverston P. Using a model of illness to aid symptom-based learning in primary care. Educ Prim Care. 2012 Nov;23(6):443-5.

- Royce CS, Hayes MM, Schwartzstein RM. Teaching Critical Thinking: A Case for Instruction in Cognitive Biases to Reduce Diagnostic Errors and Improve Patient Safety. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):187-194.

- Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J, Ilgen JS, Schmidt HG, Mamede S. The Causes of Errors in Clinical Reasoning: Cognitive Biases, Knowledge Deficits, and Dual Process Thinking. Acad Med. 2017 Jan;92(1):23-30.

- Singh H, Schiff GD, Graber ML, et al. The global burden of diagnostic errors in primary care. BMJ Quality & Safety 2017;26:484-494.

- Walton M, Woodward H, Van Staalduinen S, et al. The WHO patient safety curriculum guide for medical schools. BMJ Quality & Safety 2010;19:542-546.