- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Neck lump examination frequently appears in OSCEs and you’ll be expected to pick up the relevant clinical signs using your examination skills. This neck lump examination OSCE guide provides a clear step-by-step approach to assessing a neck lump, with an included video demonstration.

Lumps in the neck are relatively common and although the majority are benign in nature, they can sometimes be the first signs of more sinister pathology (e.g. malignancy). It is therefore essential that you are able to competently perform neck lump examination.

Red flags

The following clinical features are red flags that should raise your suspicion of malignancy in the context of a neck lump:

- A hard and fixed mass.

- The patient with the neck lump is over 35-years-old.

- The presence of a mucosal lesion in the head or neck.

- A history of persistent hoarseness or dysphagia.

- The presence of trismus.

- The presence of unilateral ear pain (referred from tongue base).

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language.

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Ask the patient to sit on a chair for the assessment.

Adequately expose the patient’s neck to the clavicles.

Ask the patient if they have any pain before proceeding with the clinical examination.

General inspection

Inspect the patient, looking for clinical signs suggestive of underlying pathology:

- Scars: may indicate previous neck surgery (e.g. thyroidectomy, lymph node biopsy/excision, radiotherapy related scarring).

- Cachexia: ongoing muscle loss that is not entirely reversed with nutritional supplementation. Cachexia is commonly associated with underlying malignancy.

- Hoarse voice: caused by compression of the larynx due to thyroid gland enlargement (e.g. thyroid malignancy).

- Dyspnoea or stridor: may indicate compression of the upper respiratory tract by a neck mass.

- Behaviour: anxiety and hyperactivity are associated with hyperthyroidism (due to sympathetic overactivity). Hypothyroidism is more likely to be associated with low mood.

- Clothing: may be inappropriate for the current temperature. Patients with hyperthyroidism suffer from heat intolerance whilst patients with hypothyroidism experience cold intolerance.

- Exophthalmos: bulging of the eye anteriorly out of the orbit associated with Graves’ disease.

Neck lump inspection

Ask the patient to point out the neck lump’s location if relevant.

Inspect the neck lump from the front and side, noting its location (e.g. anterior triangle, posterior triangle, midline).

Midline neck lump

If a midline mass is identified during the initial inspection, perform some further assessments to try and further narrow the differential diagnosis.

Swallowing

Ask the patient to swallow some water and observe the movement of the mass:

- Thyroid gland masses (e.g. a goitre) and thyroglossal cysts typically move upwards with swallowing.

- Lymph nodes will typically move very little with swallowing.

- An invasive thyroid malignancy may not move with swallowing if tethered to surrounding tissue.

Tongue protrusion

Ask the patient to protrude their tongue:

- Thyroglossal cysts will move upwards noticeably during tongue protrusion.

- Thyroid gland masses and lymph nodes will not move during tongue protrusion.

Further assessment

If you identify a midline neck lump or systemic signs indicative of thyroid disease, ask the examiner if a full thyroid status examination should be performed.

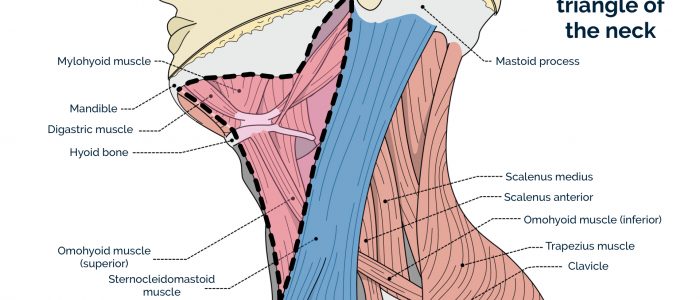

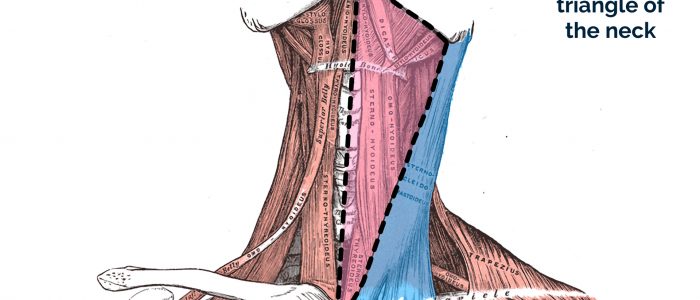

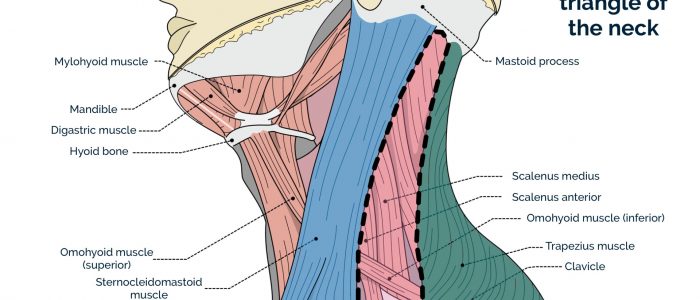

Anterior and posterior triangles of the neck

The boundaries of the anterior triangle of the neck are:

- Superior: the inferior border of the mandible.

- Medial: the midline of the neck.

- Lateral: the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid.

The boundaries of the posterior triangle of the neck are:

- Anterior: the posterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

- Posterior: the anterior margin of the trapezius muscle.

- Inferior: the middle one-third of the clavicle.

Assessing a neck lump

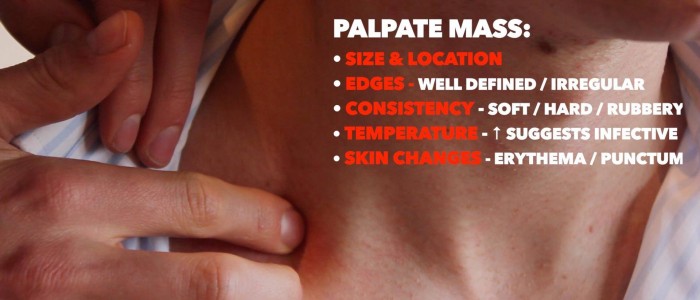

Palpate the neck lump assessing the following:

- Site: assess the lump’s location in relation to other anatomical structures (e.g. anterior triangle, posterior triangle, midline).

- Size: assess the size of the lump.

- Shape: assess the lump’s borders to determine if they feel regular or irregular.

- Consistency: determine if the lump feels soft (e.g. cyst), hard (e.g. malignancy) or rubbery (e.g. lymph node).

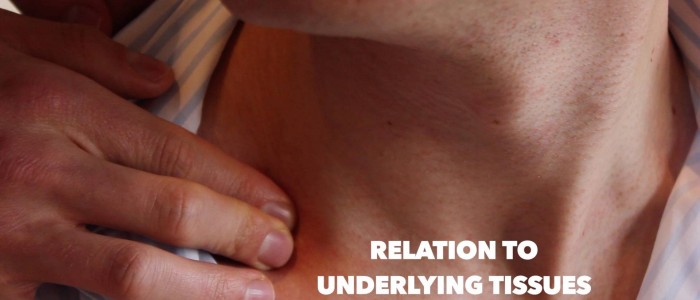

- Mobility: assess if the lump feels mobile or is tethered to other local structures. Asking the patient to turn their head as you palpate the mass can reveal if it is tethered to the underlying muscle (e.g. malignant tumour).

- Fluctuance: hold the lump by its sides and then apply pressure to the centre of the mass with another finger. If the mass is fluid-filled (e.g. cyst) then you should feel the sides bulging outwards.

- Temperature: increased warmth may suggest an inflammatory or infective cause (e.g. infected epidermoid cyst).

- Overlying skin changes: note any overlying skin changes such as erythema (e.g. inflammatory/infective aetiology) or a punctum (a pore in the epidermis indicative of an underlying epidermoid cyst).

- Pulsatility: suggests vascular origin (e.g. carotid body tumour, aneurysm).

- Tenderness: may indicate infective and/or inflammatory aetiology (e.g. ruptured epidermoid cyst, infected cyst).

Other characteristics of the lump may include:

- Transillumination: apply a light source to the lump, if it is illuminated it suggests the lump is fluid-filled (e.g. cystic hygroma).

- Vascular bruit: auscultate the lump to listen for a bruit suggestive of vascular aetiology (e.g. carotid artery aneurysm).

Branchial cyst vs cystic hygroma

A branchial cyst arises from embryological remnants of the second branchial cleft in the neck. It typically presents in young adults when an upper respiratory tract infection causes it to increase in size. The solitary smooth cyst is most often located in the anterior triangle. It is usually painless but may be painful during acute infection. A conservative approach to management may be taken if the cyst is small or alternatively surgical excision can be performed.

A cystic hygroma is a congenital lymphatic lesion which is typically identified prenatally or at birth. A cystic hygroma can arise anywhere but typically develops in the left posterior triangle of the neck. Cystic hygromas are benign but can be disfiguring and typically require surgical treatment including drainage and use of sclerosing agents to prevent reaccumulation of lymphatic fluid.

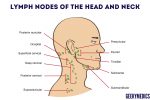

Assessing lymph nodes

Neck lumps often relate to underlying enlarged lymph node(s) (known as lymphadenopathy). Lymphadenopathy is a clinical feature of several different types of pathology including infections, lymphomas, leukaemias and local metastatic malignancy. Performing a thorough clinical assessment of all relevant lymph node groups is therefore essential.

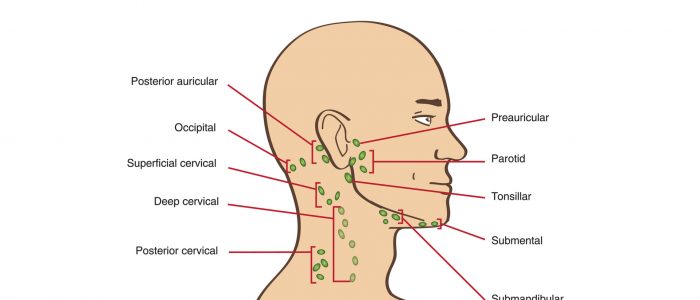

It is important to examine for lymphadenopathy in a systematic manner. There are several chains that can be easily palpated on clinical examination.

For any palpable lymph node, it’s important to assess the following characteristics to help narrow the differential diagnosis:

- Site: assess the lymph node’s location in relation to other anatomical structures.

- Size: assess the size of the lymph node.

- Shape: assess the lymph node’s borders to determine if they feel regular or irregular.

- Consistency: determine if the lymph node feels soft, hard or rubbery.

- Tenderness: note if the lymph node is tender on palpation.

- Mobility: assess if the lymph node feels mobile or is tethered to other local structures.

- Overlying skin changes: note any overlying skin changes such as erythema.

Interpretation of lymph node findings

Benign lymph nodes: typically less than 1cm, smooth, rounded, non-tender and mobile.

Reactive lymph nodes: typically smooth, rounded, tender, mobile and associated with infective symptoms (e.g. fever).

Lymphadenopathy associated with haematological malignancy: widespread enlarged rubbery lymph nodes.

Lymphadenopathy associated with metastatic cancer: regional lymphadenopathy in lymph node groups draining the affected organ. Lymph nodes typically feel hard, firm, irregular and are often tethered to local structures.

Palpation of cervical lymph nodes

1. Position the patient sitting upright and examine from behind if possible. Ask the patient to tilt their chin slightly downwards to relax the muscles of the neck and aid palpation of lymph nodes. You should also ask them to relax their hands in their lap.

2. Inspect for any evidence of lymphadenopathy or irregularity of the neck.

3. Stand behind the patient and use both hands to start palpating the neck.

4. Use the pads of the second, third and fourth fingers to press and roll the lymph nodes over the surrounding tissue to assess the various characteristics of the lymph nodes. By using both hands (one for each side) you can note any asymmetry in size, consistency and mobility of lymph nodes.

5. Start in the submental area and progress through the various lymph node chains. Any order of examination can be used, but a systematic approach will ensure no areas are missed:

- Submental

- Submandibular

- Tonsillar

- Parotid

- Pre-auricular

- Post-auricular

- Superficial cervical

- Deep cervical

- Posterior cervical

- Occipital

- Supraclavicular

Take caution when examining the anterior cervical chain that you do not compromise cerebral blood flow (due to carotid artery compression). It may be best to examine one side at a time here.

A common mistake is a “piano-playing” or “spider’s legs” technique with the fingertips over the skin rather than correctly using the pads of the second, third and fourth fingers to press and roll the lymph nodes over the surrounding tissue.

Example of a logical systematic examination of the lymph nodes

1. Start under the chin (submental lymph nodes), then move posteriorly palpating beneath the mandible (submandibular), turn upwards at the angle of the mandible (tonsillar and parotid lymph nodes) and feel anterior (preauricular lymph nodes) and posterior to the ears (posterior auricular lymph nodes).

2. Follow the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (anterior cervical chain) down to the clavicle, then palpate up behind the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (posterior cervical chain) to the mastoid process.

3. Palpate over the occipital protuberance (occipital lymph nodes).

4. Ask the patient to tilt their head (bring their ear towards their shoulder) each side in turn, and palpate behind the posterior border of the clavicle in the supraclavicular fossa (supraclavicular and infraclavicular lymph nodes).

Assessing the thyroid gland

Assessment of the thyroid gland may not be expected in an OSCE with a neck lump that is not related to the thyroid. However, to perform a thorough examination of the neck, this should be included as part of the assessment.

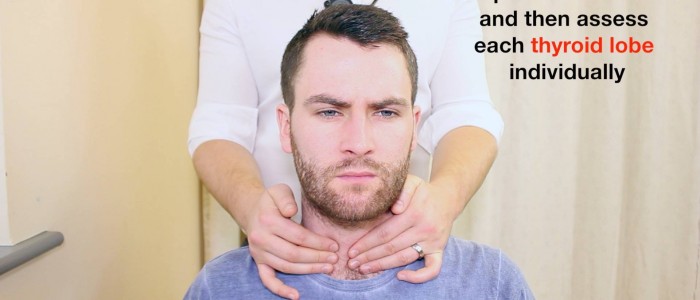

Palpation of the thyroid gland

Palpate each of the thyroid’s lobes and the isthmus:

1. Stand behind the patient and ask them to tilt their chin slightly downwards to relax the muscles of the neck to aid palpation of the thyroid gland.

2. Place the three middle fingers of each hand along the midline of the neck below the chin.

3. Locate the upper edge of the thyroid cartilage (“Adam’s apple”) with your fingers.

4. Move your fingers inferiorly until you reach the cricoid cartilage. The first two rings of the trachea are located below the cricoid cartilage and the thyroid isthmus overlies this area.

5. Palpate the thyroid isthmus using the pads of your fingers.

6. Palpate each lobe of the thyroid in turn by moving your fingers out laterally from the isthmus.

7. Ask the patient to swallow some water, whilst you feel for the symmetrical elevation of the thyroid lobes (asymmetrical elevation may suggest a unilateral thyroid mass).

8. Ask the patient to protrude their tongue (if a mass represents a thyroglossal cyst, you will feel it rise during tongue protrusion).

Characteristics of the thyroid gland

When palpating the thyroid gland, assess the following characteristics:

- Size: note if the thyroid gland feels enlarged.

- Symmetry: assess for any evidence of asymmetry between the thyroid lobes (unilateral enlargement may be caused by a thyroid nodule or malignancy).

- Consistency: assess the consistency of the thyroid gland tissue, noting any irregularities (e.g. a widespread irregular consistency would be suggestive of a multinodular goitre).

- Masses: note if there are any distinct palpable masses within the thyroid gland’s tissue (e.g. solitary thyroid nodule or thyroid malignancy).

- Palpable thrill: assess for evidence of a palpable thrill caused by increased vascularity of the thyroid gland due to hyperthyroidism (suggestive of Graves’ disease).

Thyroglossal cyst

Thyroglossal cysts are the most common congenital abnormality of the neck and arise as a result of the persistence of the thyroglossal duct. The thyroglossal duct is the tract by which the thyroid gland descends during embryological development to its final position in the front of the neck. The tongue is attached to the thyroglossal duct, which is why thyroglossal cysts rise during tongue protrusion.

Assessing the submandibular gland

Assessment of the submandibular gland may be expected if the neck lump is located in the submandibular region.

Palpating the submandibular gland

Each submandibular gland can be palpated inferior and posterior to the body of the mandible. Move inwards from the inferior border of the mandible near its angle with the patient’s head tilted forward. To assess the gland thoroughly, you should perform bimanual palpation with one gloved finger palpating the floor of the mouth whilst the other palpates externally underneath the mandible.

Submandibular gland swellings are usually singular, whereas lymphadenopathy typically involves multiple nodes). Salivary duct calculi are relatively common and may be felt as a firm mass within the gland.

See our guide to oral cavity examination for more details.

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

Example summary

“Today I examined Mr Smith, a 32-year-old male. On general inspection, the patient appeared comfortable at rest. There were no objects or medical equipment around the bed of relevance.”

“Inspection of the neck was unremarkable, but palpation revealed a 1 x 2 cm mass in the left posterior triangle. The mass was mildly tender on palpation with overlying erythema and a visible punctum. The mass was smooth and round in shape. There was no evidence of tethering to the underlying tissue, however, the lesion did appear to be tethered to the epidermis. There was also no palpable lymphadenopathy in the cervical region.”

“In summary, these findings are consistent with a ruptured and/or infected epidermoid cyst.”

“For completeness, I would like to perform the following further assessments and investigations.”

Further assessments and investigations

- Thyroid status examination and thyroid function tests (TSH, T3, T4): if a midline lump is present.

- Examination of the lymphoreticular system: if lymphoma or leukaemia is suspected.

- Examination of oral cavity, oropharynx and nasal cavity: to exclude a mucosal lesion.

- Routine blood tests such as FBC, U&Es, CRP: useful if considering infection or malignancy.

- Ultrasound scan and other imaging (e.g. CT/MRI): to determine aetiology.

- Fine needle aspiration: to allow histological diagnosis.

- Early referral to ENT: if there is suspicion of malignancy.

Differential diagnosis of a neck lump

The location of the lump within the neck can sometimes be useful in narrowing the differential diagnosis, particularly when combined with other clinical findings and investigation results.

Causes of a midline neck lump

- Lymph node: often multiple and associated with underlying infection or malignancy.

- Lipoma: a solitary painless, rubbery, smooth mass.

- Dermoid cyst: formed along the lines of embryological fusion. Dermoid cysts present as painless swellings that do not move with tongue protrusion (more common in children and young adults).

- Epidermoid cyst: a solitary painless mass (can be painful with overlying erythema if ruptured/infected) that has an associated punctum in the epidermis overlying the lesion. They are tethered to the epidermis and contain keratin.

- Enlarged thyroid gland: typically located below the thyroid cartilage (see our thyroid examination guide for more details).

- Thyroid nodule: may be single or multiple and represent adenomas, cysts or malignancy.

- Thyroglossal cysts: a painless, smooth fluctuant mass that rises on tongue protrusion.

- Laryngocele: a reducible tense mass that can increase in size during sneezing or nose blowing.

Causes of a neck lump located in the anterior triangle

The anterior triangle refers to the area of the neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle:

- Lymph node: often multiple and associated with underlying infection or malignancy.

- Lipoma: a solitary painless, rubbery, smooth mass.

- Epidermoid cyst: a solitary painless mass (can be painful with overlying erythema if ruptured/infected) that has an associated punctum in the epidermis overlying the lesion. They are tethered to the epidermis and contain keratin.

- Submandibular gland swelling: typically located medial to the angle of the mandible and may be caused by a salivary gland stone (sialolithiasis) and/or infection of the gland (sialoadenitis).

- Branchial cyst: present from birth and typically noticed in early adulthood when it becomes swollen due to infection.

- Carotid artery aneurysm: a pulsatile mass with an audible bruit on auscultation.

- Carotid body tumour: pulsatile and can be moved side to side but not up and down (due to the carotid sheath).

- Laryngocele: a reducible tense mass which increases in size during sneezing or nose blowing.

Causes of a neck lump located in the posterior triangle

The posterior triangle refers to the area of the neck posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle:

- Lymph node: often multiple and associated with underlying infection or malignancy.

- Lipoma: a solitary painless, rubbery, smooth mass.

- Epidermoid cyst: a solitary painless mass (can be painful with overlying erythema if ruptured/infected) that has an associated punctum in the epidermis overlying the lesion. They are tethered to the epidermis and contain keratin.

- Subclavian artery aneurysm: a pulsatile mass with an audible bruit on auscultation.

- Pharyngeal pouch: a reducible mass.

- Cystic hygroma: a fluctuant mass which transilluminates typically located on the left side of the neck.

- Branchial cyst: present from birth and typically noticed in early adulthood when it becomes swollen due to infection.

- Mass in the tail of the parotid gland: typically associated with pleomorphic adenoma or primary parotid malignancy.

Reviewers

Mr Ben Cosway

Senior ENT Registrar

Mr Krishan Ramdoo

Senior ENT Registrar

References

- Steven Fruitsmaak. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Epidermoid cyst. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Vardhan Kothapalli. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Cystic hygroma. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- BigBill58. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Branchial cyst. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Bp20151130. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Thyroglossal cyst. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Drahreg01. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Goitre. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- Olek Remesz. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Licence: CC BY.

- Coronation Dental Specialty Group. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Lymphadenopathy. Licence: CC BY-SA.

- James Heilman, MD. Adapted by Geeky Medics. Submandibular gland. Licence: CC BY-SA.