- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

The nerve supply to the upper limb is an important and complex topic which will inevitably appear in anatomy questions, clinical case scenarios and OSCEs. It is also very relevant to clinical practice.

This article will focus on the five terminal nerve branches of the brachial plexus which supply the upper limb. These are the musculocutaneous nerve, the axillary nerve, the radial nerve, the median nerve and the ulnar nerve. We will cover their anatomy and function, as well as the clinical features you would expect to find with a nerve injury.

For more information on the muscles of the upper limb, see the Geeky Medics section on upper limb anatomy.

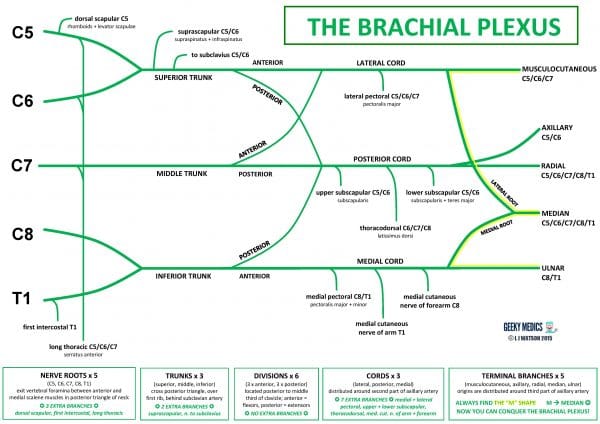

Structure of the brachial plexus

The nerve supply to the upper limb is almost entirely supplied by the brachial plexus, a complex intercommunicating network of nerves formed in the neck by spinal nerve roots C5, C6, C7, C8 and T1. The brachial plexus itself in more detail in a separate article here.

Figure 1 summarises the structure and branches of the brachial plexus.

The three cords branch to form the five terminal nerve branches which supply the upper limb:

- The lateral cord gives the musculocutaneous nerve and the lateral root of the median nerve

- The posterior cord gives the axillary nerve and the radial nerve

- The medial cord gives the medial root of the median nerve and the ulnar nerve

The origins of these five nerves are distributed around the third part of the axillary artery.

The musculocutaneous, median and ulnar nerves lie anteriorly and form a characteristic “M” shape around the axillary artery, which is an easy landmark to find on a prosection. When given a diagram or prosection of the brachial plexus to label in exams, look for the “M” shape!

Musculocutaneous nerve (C5/C6/C7)

Origin

The lateral cord of brachial plexus, formed from anterior divisions of superior and middle trunks.

Course

The musculocutaneous leaves the axilla by piercing coracobrachialis muscle. It then passes down the arm beneath biceps muscle and ends as the lateral cutaneous nerve of forearm.

Sensory supply

It supplies skin of lateral forearm.

Motor supply

The musculocutaneous nerve innervates the anterior compartment of arm (BBC):

- Biceps: flexes elbow, supinates forearm

- Brachialis: flexes elbow

- Coracobrachialis: flexes and adducts the arm at the glenohumeral joint

Common injures

Musculocutaneous nerve injuries are rare, as the nerve is protected beneath the bulk of the biceps muscle. It may be damaged by stab wounds to the upper arm

Clinical features: Musculocutaneous nerve palsy

Clinical features of musculocutaneous nerve palsy include:

- Sensory loss: numbness over lateral forearm

- Motor deficit: paralysis of anterior compartment of arm with very weak elbow flexion and weak forearm supination. Absent biceps reflex.

- Deformity: wasting of the anterior compartment of the arm. The elbow usually held in extension with forearm pronated.

Axillary nerve (C5/C6)

Origin

The posterior cord of brachial plexus formed from posterior division of upper trunk.

Course

The axillary nerve passes beneath the shoulder joint through the quadrangular space with the posterior circumflex humeral artery. It then wraps around the surgical neck of the humerus.

Sensory supply

The axillary nerve supplies the “sergeant’s patch” of skin over the lower part of deltoid muscle.

Motor supply

The axillary nerve innervates the following shoulder muscles:

- Deltoid: abducts, flexes and extends shoulder

- Teres minor: externally rotates shoulder, forms part of rotator cuff which stabilises shoulder joint

Common injuries

Common injuries affecting the axillary nerve include:

- Fracture of surgical neck of humerus

- Stab wounds to posterior shoulder

- Anterior shoulder dislocation

- Pressure of crutches on armpits (“crutch palsy”)

Clinical features: Axillary nerve palsy

Clinical features of axillary nerve palsy include:

- Sensory loss: numbness over “sergeant’s patch”

- Motor deficit: paralysis of deltoid leading to very weak shoulder abduction from 15-90°; weak shoulder flexion and extension. Paralysis of teres minor leading to weak shoulder external rotation.

- Deformity: wasting of deltoid muscle, making the bones of the shoulder joint very prominent and obvious. The shoulder may appear adducted and internally rotated.

Radial nerve (C5/C6/C7/C8/T1)

Origin

The radial nerve originates from the posterior cord formed from posterior divisions of all three trunks.

Course

The radial nerve passes behind the axillary artery and through the triangular interval to enter the posterior compartment of the arm. It then winds around the spiral groove of the humerus with the profunda brachii artery, between the heads of triceps muscle.

It enters the antecubital fossa in front of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, between the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles

The radial nerve then branches in the proximal forearm into two terminal branches:

- Superficial branch (mainly sensory): descends under brachioradialis muscle to end in the dorsum of the hand

- Deep branch (mainly motor): pierces supinator muscle and descends along the posterior interosseous membrane with the posterior interosseous artery

Sensory supply

The radial nerve is responsible for the sensory supply to:

- Posterior arm and forearm

- Lateral ⅔ of dorsum of hand

- Proximal dorsal aspect of lateral 3½ fingers (thumb, index, middle and half of ring finger)

Motor supply

The radial nerve supplies the triceps in the posterior compartment of the arm. The triceps extends and adducts shoulder and extends elbow.

The radial nerve innervates the following muscles in the posterior compartment of the forearm:

- Brachioradialis: flexes elbow

- Anconeus: extends elbow, stabilises elbow joint

- Supinator: supinates forearm

- Extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis: extend and abduct wrist

- Extensor carpi ulnaris: extends and adducts wrist

- Extensor digitorum, extensor pollicis longus and brevis, extensor indicis and extensor digiti minimi: extend thumb and fingers at MCPJs and IPJs

- Abductor pollicis longus: abducts thumb

Common injuries

Common injuries affecting the radial nerve include:

- Fractures of proximal humerus, shaft of humerus or radius

- Stab wounds to antecubital fossa, forearm or wrist (this includes blood tests and cannulation)

- Pressure of crutches on armpits (“crutch palsy”)

- The patient falling asleep with arm hanging over the back of a chair, classically whilst drunk (“Saturday night palsy”)

- Somebody else falling asleep with their head lying on the patient’s arm (“honeymoon palsy”)

- Excessively tight plaster casts, wristbands or handcuffs

- Prolonged tourniquet use on the arm arm, for example during orthopaedic or plastics procedures

Clinical features: Radial nerve palsy

Clinical features of radial nerve palsy include:

- Sensory loss: numbness of skin over posterior arm, posterior forearm and radial distribution of dorsum of hand

- Motor deficit:

- paralysis of posterior compartment of arm: weak elbow extension

- paralysis of posterior compartment of forearm: weak wrist extension, weak thumb extension and finger MCPJ extension

- Finger IPJ extension is still possible due to intact nerve supply to the lumbrical muscles of the hand

- Absent triceps and supinator reflexes

- Deformity: “Wrist drop” deformity at rest and on attempted wrist extension (Figure 2). The patient cannot extend their wrist/fingers, resulting in unopposed wrist flexion. In the classical description of a radial nerve injury, the forearm is also pronated, the fingers are flexed, and the thumb adducted. There may also be wasting of triceps and posterior compartment of forearm.

Median nerve (C5/C6/C7/C8/T1)

Origin

The lateral and medial cords of the brachial plexus. The lateral root arises from anterior divisions of superior and middle trunks. The medial root arises from anterior division of inferior trunk.

Course

The median nerve runs down the arm with the brachial artery. It initially lies lateral to the artery, then crosses over to lie medial to it about halfway down the arm.

The nerve then passes through the medial part of the antecubital fossa between the two heads of pronator teres muscle.

It travels through the anterior forearm between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus muscles and gives three main branches:

- Anterior interosseous nerve: descends along the anterior interosseous membrane with anterior interosseous artery

- Deep branch: enters hand through the carpal tunnel beneath the flexor retinaculum of the wrist, between flexor carpi radialis and flexor digitorum superficialis tendons

- Superficial/palmar cutaneous branch: arises just before the wrist and pierces the palmar carpal ligament to enter the palm over the top of the carpal tunnel – this nerve is therefore not affected by carpal tunnel syndrome

Sensory supply

The median nerve does not supply any sensory innervation to the axilla or upper arm.

In the hand, the median nerve supplies:

- Skin over thenar eminence

- Lateral ⅔ palm of hand

- Palmar aspect of lateral 3½ fingers

- Dorsal fingertips of lateral 3½ fingers (thumb, index, middle and half of ring finger)

Motor supply

The median nerve does not supply any motor innervation to the axilla or upper arm

The median nerve supplies all muscles of anterior compartment of forearm except flexor carpi ulnaris and the medial two parts of flexor digitorum profundus:

- Pronator teres and pronator quadratus: pronate forearm

- Flexor carpi radialis: flexes and abducts wrist

- Palmaris longus: flexes wrist and tenses palmar aponeurosis

- Flexor digitorum superficialis: flexes fingers at PIPJs

- Lateral two parts of flexor digitorum profundus: flex index and middle fingers at DIPJs

- Flexor pollicis longus: flexes thumb at IPJ

The median nerve also supplies the intrinsic muscles of hand (LOAF muscles):

- Lateral two lumbricals: flex MCPJs and extend IPJs of index and middle finger

- Opponens pollicis: opposes thumb

- Abductor pollicis brevis: abducts thumb

- Flexor pollicis brevis: flexes thumb at MCPJ

Common injuries

Common injuries affecting the median nerve include:

- Supracondylar fractures of humerus

- Stab wounds to antecubital fossa, forearm of wrist (this includes blood tests and cannulation!)

- Deep wrist lacerations inflicted during deliberate self-harm

- Compression by carpal tunnel syndrome

Clinical features: Median nerve palsy

Clinical features of median nerve palsy include:

- Sensory loss: numbness of skin over thenar eminence and median distribution of hand. However, in carpal tunnel syndrome, sensation to the palm is usually preserved due to an intact palmar cutaneous branch.

- Motor deficit:

- Paralysis of most of anterior compartment of forearm: weak forearm pronation, wrist flexion and abduction, and weak finger flexion with preservation of DIPJ flexion at ring and little fingers.

- Paralysis of thenar eminence: weak pincer grip and overall grip strength, weak thumb opposition.

- Deformity: “Hand of benediction” deformity on attempted finger flexion, the patient cannot flex their index or middle fingers, resulting in unopposed extension of those two fingers (Figure 3). They cannot make a fist with all of their fingers. Wasting of anterior compartment of forearm and thenar eminence

Ulnar nerve (C8/T1)

Origin

The medial cord of brachial plexus, formed from anterior division of inferior trunk

Course

The ulnar nerve runs down the arm on the medial side of the brachial artery. It passes behind the medial epicondyle of the humerus and enters the forearm between the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris.

The nerve travels through the anterior compartment of the forearm beneath flexor carpi ulnaris with the ulnar artery. It then enters the palm of the hand through Guyon’s canal

Sensory supply

The ulnar nerve does not supply any sensory innervation to the axilla or upper arm.

In the hand, the ulnar nerve supplies:

- Skin over hypothenar eminence

- Medial ⅓ palm of hand

- Palmar aspect of the medial 1½ fingers

- Medial ⅓ dorsum of hand

- Dorsal aspect of medial 1½ fingers (little finger and half of ring finger)

Motor supply

The ulnar nerve innervates two muscles in the anterior compartment of the forearm:

- Flexor carpi ulnaris: flexes and adducts wrist

- Medial two parts of flexor digitorum profundus: flex ring and little fingers at DIPJs

The ulnar nerve innervates most of the intrinsic muscles of the hand (HILA muscles):

- Hypothenar eminence: opponens digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi brevis and abductor digiti minimi: oppose, flex and abduct little finger

- Interossei: palmar interossei adduct, dorsal interossei abduct

- Medial two lumbricals: flex MCPJs and extend IPJs of ring and little finger

- Adductor pollicis: adducts thumb. adductor pollicis is not part of the thenar eminence and actually lies deep beneath it as a separate structure.

In addition, the superficial branch of the ulnar nerve innervates palmaris brevis.

Common injuries

Common injuries affecting the ulnar nerve include:

- Supracondylar fractures of humerus

- Fractures or soft tissue injuries to medial epicondyle of humerus

- Stab wounds to forearm or wrist (this include blood tests and cannulation!)

- Compression either at the cubital tunnel in the elbow or at Guyon’s canal in the wrist

Clinical features: Ulnar nerve palsy

Clinical features of ulnar nerve palsy include:

- Sensory loss: numbness over hypothenar eminence and ulnar distribution of hand

- Motor deficit:

- Paralysis of flexor carpi ulnaris: weak wrist flexion and adduction

- Paralysis of medial two parts of flexor digitorum profundus: weak flexion of ring and little finger DIPJs

- Paralysis of most of the intrinsic muscles of the hand: weak MCPJ flexion and IPJ extension of ring and little fingers, loss of finger abduction and adduction, loss of opposition of little finger

- Deformity: “Claw hand” deformity at rest and on attempted finger extension: the patient cannot extend the IPJs of their ring or little fingers, resulting in fixed flexion of the IPJs and hyperextension of the MCPJs of these two fingers (Figure 4).

The clawed appearance is most pronounced when the nerve is injured at the wrist, for example by compression in Guyon’s canal, as the function of flexor digitorum profundus will be preserved. A claw hand affecting all four fingers is much less common and is usually due to a lesion of the lower part of brachial plexus, such as Klumpke’s palsy. wasting of hypothenar eminence and intrinsic muscles of hand

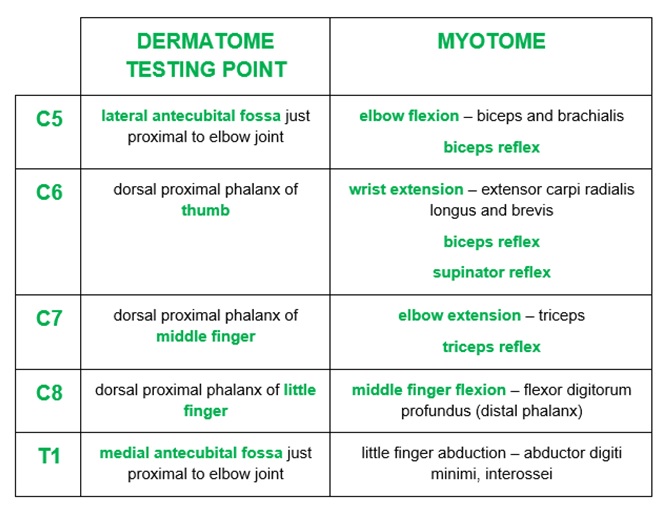

Clinical anatomy

The sensory supply to the upper limb can be broken down into dermatomes (the area supplied by each spinal nerve root) and peripheral nerve territories. The motor supply to the upper limb can also be broken down into myotomes (the movements which test individual spinal nerve roots) as well as peripheral nerve functions (Figure 5).

For more information on examining the upper limb, see the Geeky Medics OSCE guide to neurological examination of the upper limb.

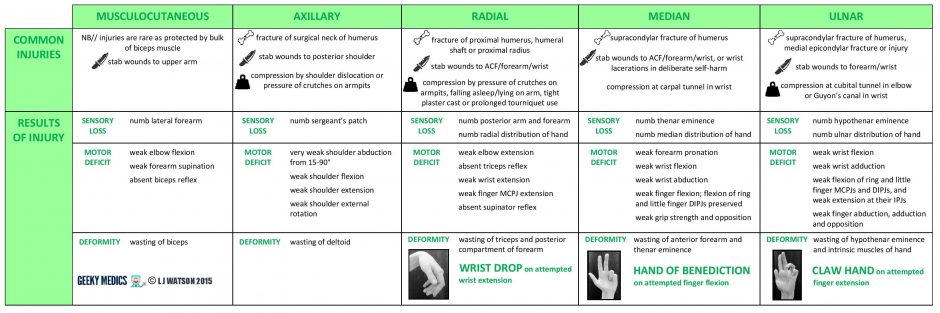

Peripheral nerve injuries

The nerve supply to the upper limb is commonly damaged by fractures, penetrating trauma and external compression. Patients with neurological signs following upper limb injuries may appear in OSCE stations.

There are several types of nerve injuries:

- Neurapraxia: the nerve is stretched and damaged but not torn

- Rupture: the nerve is torn at a point along its length

- Axonotmesis: the nerve fibre is partially severed: the axon and myelin sheath are torn but the surrounding epineurium, perineurium and connective tissues are preserved. Natural recovery is possible through axonal regeneration, so these injuries can often be managed conservatively with support and physiotherapy.

- Neurotmesis: the nerve fibre is completely severed. There is no prospect of natural recovery, so this type of injury requires surgery to restore function.

- Avulsion: the nerve root is torn off the spinal cord at its origin. This can happen in brachial plexus injuries but would not usually cause injury to individual upper limb nerves.

- Post-traumatic neuroma: a growth of scar tissue at the site of a previous nerve injury, which leads to compression

For more information on brachial plexus injuries, see the Geeky Medics guide to the brachial plexus.

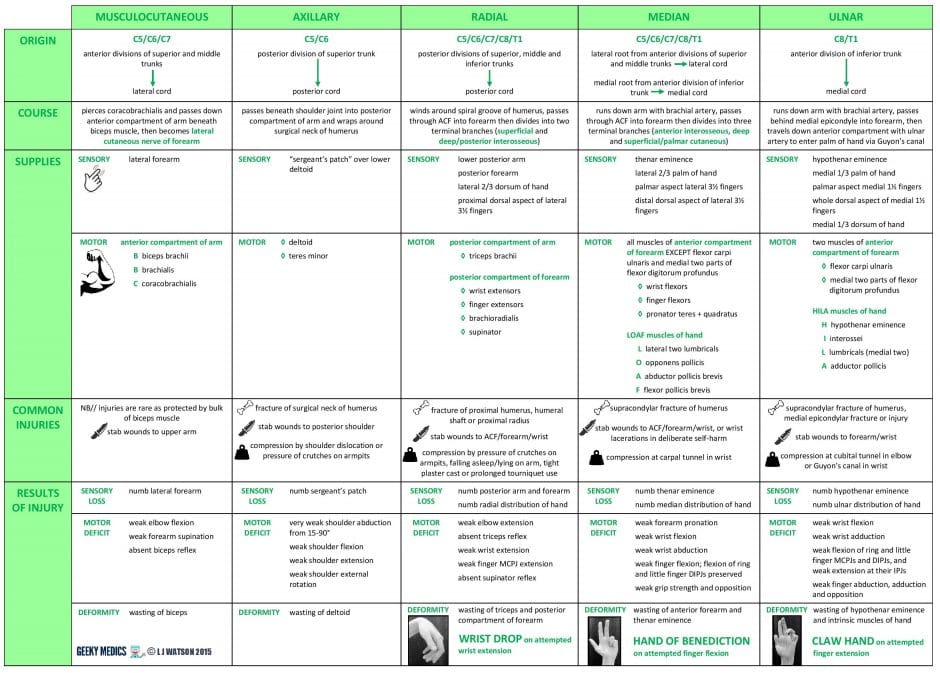

Summary table

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- International Standards for Classification of Spinal Cord Injury 2011 Revised Edition, available from [LINK]

- Netter FH. Atlas of Human Anatomy, 5th Edition. Published in 2010

- Sinnatamby CS. Last’s Anatomy, 12th Edition. Published in 2011

- Snell RS. Clinical Anatomy by Regions, 9th Edition. Published in 2011