- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

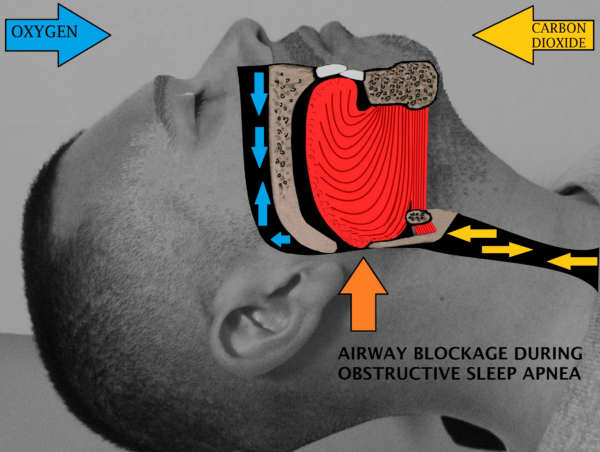

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a sleep disorder that is characterised by recurrent episodes of upper airway obstruction during sleep, which results in apnoea (temporary cessation of breathing) or hypopnoea (temporary decreases in breathing).1

OSA has a prevalence of 1.5 million in the United Kingdom, but it is believed that many more patients remain undiagnosed.2

Aetiology

A narrow upper airway is more likely to collapse than a wide upper airway.

OSA patients have narrow upper airways, which can be due to fat deposition in the pharyngeal wall/tongue, or abnormal skeletal features (such as posterior positioning of the mandible).3

During sleep, all muscles relax, including the pharyngeal dilator muscles. This increases the risk of upper airway collapse.4

Furthermore, some OSA patients have inadequate genioglossus muscle responsiveness to airway collapse during sleep.5

The collapse of the upper airway can cause hypoxaemia and hypercapnia. This is detected by peripheral chemoreceptors, which stimulate the respiratory control centre in the brainstem and the sympathetic nervous system. This leads to arousal from sleep and activation of the pharyngeal dilator muscles, resulting in airway patency.6

If sleep resumes after this brief arousal, then the upper airway can collapse again. This cycle can repeat several hundred times in a night.

Risk factors

Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnoea include:

- Obesity

- Craniofacial abnormalities (such as posterior positioning of the mandible)

- Increased soft tissue volume (such as adenotonsillar hypertrophy)

- Male sex

- Down’s syndrome

Clinical features

History

Typical symptoms of OSA include:

- Excessive daytime somnolence: this can be quantified using the Epworth sleepiness scale. Patients often wake up feeling unrefreshed.

- Chronic morning headache: this could be due to hypercapnia-induced cerebral vasodilation8

- Arousal during sleep with choking/gasping: this may be observed by the patient’s bed partner

- Habitual snoring

- Restless sleep

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Surgical history: difficult intubations and tooth extractions may lead to craniofacial abnormalities9

- Family history of OSA

- Occupational history: patients with excessive sleepiness for >3 months must inform the DVLA.10 This may be pertinent if the patient’s occupation involves a lot of driving

Clinical examination

A full respiratory examination should be performed in suspected cases of OSA.

Typical clinical findings in OSA include:

- Obesity: leads to large neck circumference

- Craniofacial abnormalities (such as posterior positioning of the mandible)

- Increased soft tissue volume (such as adenotonsillar hypertrophy)

Differential diagnoses

The presenting complaints of OSA have important differential diagnoses. Table 1 outlines these differential diagnoses, and the features which differentiate them from OSA.

Table 1. Differential diagnoses of OSA

| Differential diagnosis | Features differentiating from OSA |

|

Central sleep apnoea |

|

|

Periodic limb movement disorder (previously known as restless leg syndrome) |

|

|

Laryngospasm secondary to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease |

|

|

Poor sleep hygiene |

|

Investigations

Relevant investigations for OSA include:

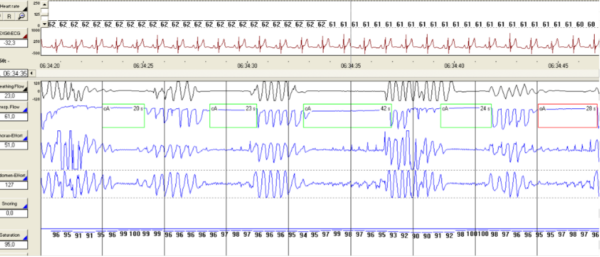

- Polysomnography (Figures 2 and 3): the gold-standard diagnostic test for OSA. This usually involves a patient being monitored in a sleep laboratory overnight. Polysomnography evaluates many body functions, including brain activity (electroencephalogram), muscle activity (electromyogram) and respiratory activity (pulse oximetry and airway capnography).11 OSA is diagnosed if the apnoea-hypopnoea index (number of apnoeic/hypnoeic events per hour) is ≥15 per hour, or ≥5 per hour if there are OSA symptoms/cardiovascular comorbidities.1

- Respiratory polygraphy: this is similar to polysomnography, but does not usually contain an electroencephalogram or electromyogram. Respiratory polygraphy can be performed at the patient’s home. It is interpreted by a sleep specialist.4

- Overnight pulse oximetry: this can also be performed at home and can demonstrate apnoeic episodes overnight.

Management

Conservative management

Conservative management of OSA includes:

- Weight-loss regimens

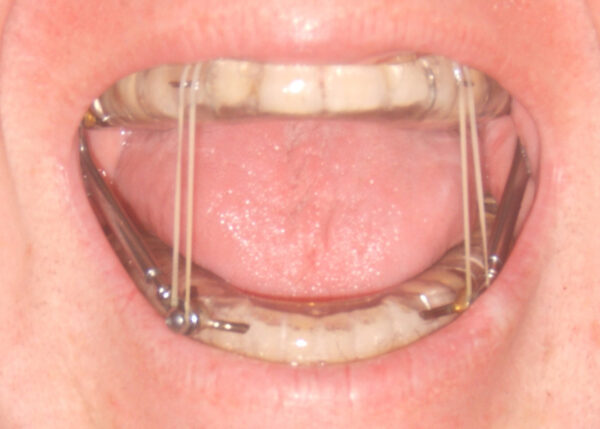

- Oral appliances (such as mandibular advancement devices and tongue retaining devices) (Figure 4): these devices reduce upper airway collapsibility by widening the upper airway14

- Sleeping in the lateral position: the upper airway becomes more circular when lying in the lateral position, which reduces the risk of upper airway collapse15

Ventilatory management

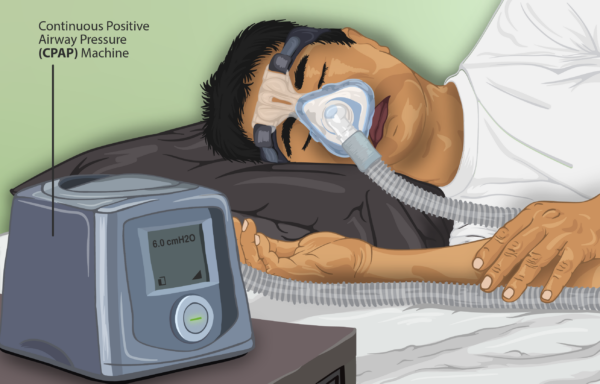

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) (Figure 5) is used to hold the upper airway open during sleep. This is the gold-standard treatment for severe OSA (apnoea-hypopnoea index ≥30 per hour).

Medical management

Dopamine reuptake inhibitors (such as modafinil and solriamfetol) can reduce somnolence, however, these are rarely used in OSA.

Surgical management

Surgical management of OSA includes:

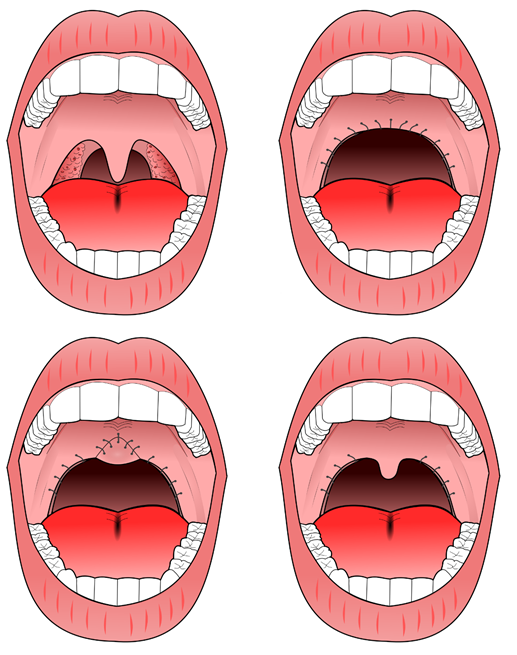

- Upper airway surgery: may be indicated if CPAP or oral appliances fail. Options include uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (resecting tissue in the throat to increase the upper airway size, Figure 6) and tonsillectomy (particularly in patients with adenotonsillar hypertrophy)

- Bariatric surgery

Complications

Disease-related complications

Disease-related complications may include:

- Cardiovascular disease (such as hypertension and myocardial infarction): mechanisms include increased levels of oxidative stress and sympathetic nervous system activation19

- Diabetes: increased sympathetic nervous system activation inhibits the release of hormones that are involved in glucose metabolism20

- Motor vehicle accidents: due to daytime somnolence

Treatment-related complications

Treatment-related complications may include:

- Due to CPAP: dry mouth, nasal congestion, skin irritation

- Due to upper airway surgery: nasopharyngeal regurgitation, voice change, post-operative bleeding

Key points

- Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a sleep disorder that is characterised by recurrent apnoeic/hyponeic episodes at night, due to upper airway collapse

- Common risk factors include obesity and craniofacial abnormalities

- The main clinical features are daytime somnolence (quantified using the Epworth sleepiness scale), morning headache and snoring

- A diagnosis of OSA is based on polysomnography

- Management includes weight loss regimens, upper airway appliances and CPAP

- The major complications are cardiovascular disease and diabetes

Feedback

Please click here to fill out the feedback form, which should take less than 1 minute of your time. Feedback is vital as it allows authors to improve their articles, leading to even better content on Geeky Medics!

Reviewer

Dr Neeraj Shah

Respiratory Medicine Registrar

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Semelka M et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea in Adults. American Family Physician. Published in 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- British Lung Foundation. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: toolkit for commissioning and planning local NHS services in the UK. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Gottlieb D and Punjabi N. Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: A Review. Journal of the American Medical Association. Published in 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Levy P et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome. Nature Reviews. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Eckert D et al. Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnoea. Identification of novel therapeutic targets. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. Published in 2013. Available from: [LINK]

- Andrade D et al. Ventilatory and Autonomic Regulation in Sleep Apnoea Syndrome: A Potential Protective Role for Erythropoietin. Frontiers in Physiology. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Drcamachoent. OSA Mechanism. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Spalka J et al. Morning Headache as an Obstructive Sleep Apnoea-Related Symptom among Sleep Clinic Patients – A Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Sciences. Published in 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- BMJ Best Practice. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea in Adults. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Gov.uk. Excessive sleepiness and driving. Published in 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Boulos M et al. Normal polysomnography parameters in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Eumetaxas. Polysomnography Reading. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Somnomed C. Polysomnography. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Marklund M et al. Update on oral appliance therapy. European Respiratory Review. Published in 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Jokic R et al. Positional treatment vs continuous positive airway pressure in patients with positional obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Chest. Published in 1999. Available from: [LINK]

- DMY. Mandibular Advancement Device. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Myupchar. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Drcamachoent. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. License: [CC BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]

- Tietjens J et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea in Cardiovascular Disease: A Review of the Literature and Proposed Multidisciplinary Clinical Management Strategy. Journal of the American Heart Association. Published in 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Reutrakul S and Mokhlesi B. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and Diabetes. Chest. Published in 2017. Available from: [LINK]