- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

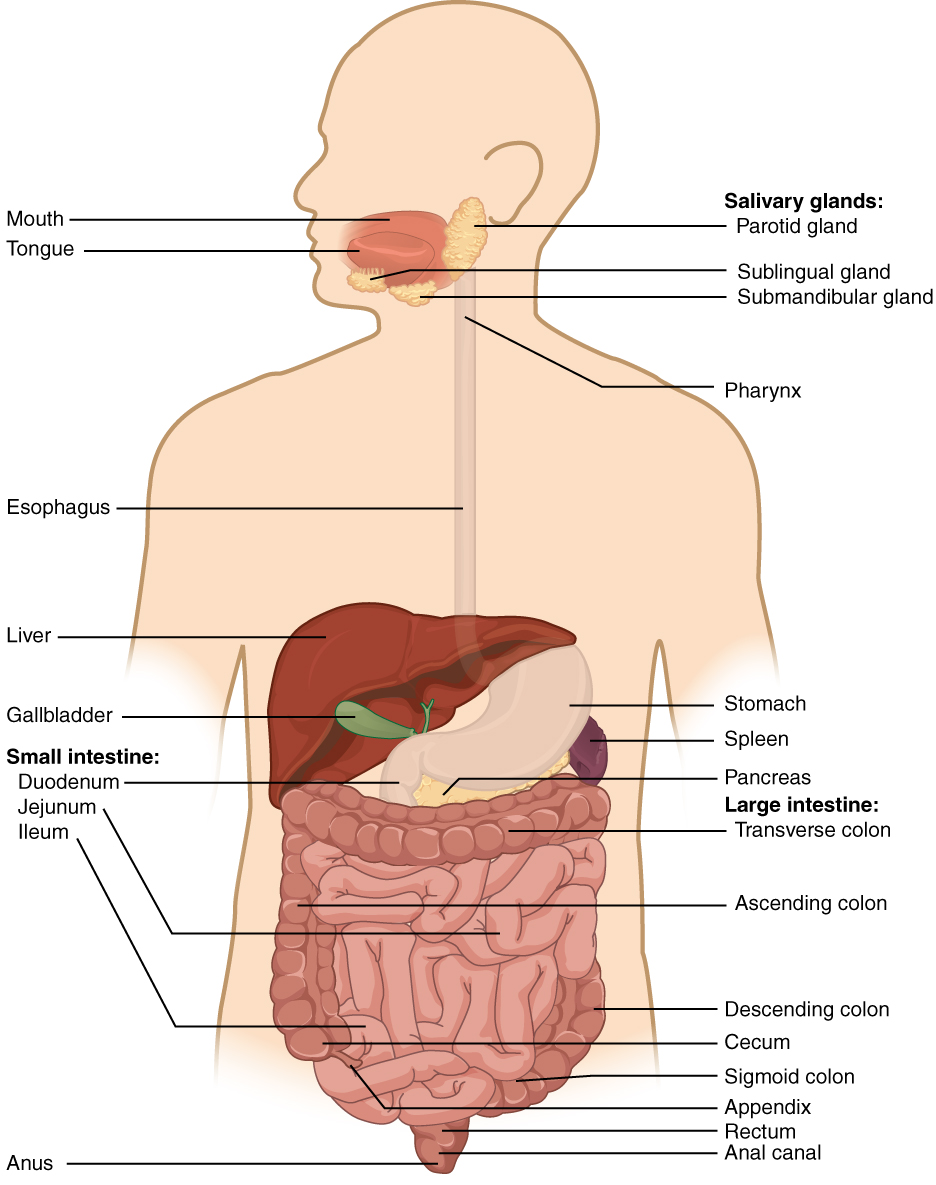

The digestive system, also known as the gastrointestinal system, regulates food intake, enables the digestion and absorption of nutrients and enables waste elimination.1

This digestive system is responsible for transforming the variety of foods consumed into usable energy and building blocks for bodily functions, growth and repair.1,2

The primary digestive tract is the pathway that allows for food to be moved along the tract, digested, absorbed and waste excreted.2

The accessory digestive tract refers to the group of organs that synthesise, and secrete enzymes that allow for the chemical breakdown of food products.2

Organs of the digestive system

Mouth

Digestion begins in the mouth with mastication (chewing). Food is broken down in a bolus.1,2

Pharynx

The pharynx pushes the food bolus from the mouth to the oesophagus, whilst protecting the airway.1,2

Oesophagus

The oesophagus is a muscular tube connecting the pharynx and the stomach, allowing for the conduction of the food bolus.1,2

It has two sphincters, the upper and the lower oesophageal sphincters. The upper sphincter allows food to enter the oesophagus, whereas the lower sphincter controls the entry of the food bolus into the stomach.

Stomach

The stomach is a reservoir for food that is consumed before digestion begins. Food is mechanically churned and mixed with gastric acid forming chyme. The pyloric sphincter connects to the duodenum enabling the controlled release of chyme into the duodenum for further digestion and absorption.1,2

Small intestine

The small intestine is divided into three structural sections:1,2

- Duodenum: approximately 25cm in length and surrounds the head of the pancreas. Chyme enters the duodenum, as do digestive enzymes produced by the pancreas and bile from the liver. Glands in the duodenum secrete bicarbonate, which neutralises the acidic stomach.

- Jejunum: approximately 2.5 metres long, containing large amounts of villi that increase its surface area. The majority of absorption of nutrients occurs in the jejunum.

- Ileum: the last section of the small intestine and is approximately 3 metres long. Vitamin B12, bile acids and any remaining nutrients are absorbed here.

Large intestine

The large intestine is the final part of the digestive system. The main function is to remove water from waste material and form faeces for excretion.1,2

The large intestine is made up of:

- Caecum: the first part of the large intestine that connects with the ileum. The appendix is located in the caecum.

- Colon: divided into ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid sections. In the colon, water, electrolytes and vitamins are absorbed, compacting the faecal matter.

- Rectum: provides a storage area for faeces before defecation. The physical stretch of the rectal walls leads to the urge to defecate.

- Anus: the canal that faeces exits the body through. There are two sphincters, the internal and external anal sphincters. When the urge to defecate occurs, the internal anal sphincter relaxes, allowing faeces through. Being under somatic control, the external sphincter will relax when defecation is appropriate!

Accessory organs

Salivary glands

Located in the oral cavity, salivary glands secrete saliva. Saliva contains some proteins and enzymes that lubricate the mouth and begin the chemical digestion of food.1,2

Liver

The liver produces bile, which further enables chemical digestion by allowing for fat emulsification. Via the biliary system, bile enters the small intestine in the duodenum.1,2

Pancreas

The pancreas produces digestive enzymes, bicarbonate and electrolytes that enter the duodenum via the pancreatic duct. These act to help neutralise stomach acid and break down proteins, fats and carbohydrates.1,2

Gallbladder

When bile is produced but not immediately needed, it flows to the gallbladder, where is concentrated for storage. It is then released as required for digestion.1,2

Clinical relevance: Cholecystectomy

Gallstones are common, and some patients require the removal of their gallbladder (a cholecystectomy). Following a cholecystectomy, the patient is no longer able to store and concentrate bile. As the liver can only produce a certain about of bile at a given time, bile becomes a finite resource, and with no stores to draw upon in the event of a fatty meal, fat digestion can be affected, particularly in the first few months after the procedure.

Symptoms of fat malabsorption after cholecystectomy include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, malodourous diarrhoea (steatorrhea) and increased flatulence.

Fats should not be avoided but slowly reintroduced into a patient’s diet post-procedure to ascertain tolerance levels. Complete avoidance of fats will likely lead to vitamin deficiency and low caloric intake.1

Neurovascular supply

Arterial supply

Arterial supply of the digestive system is via branches of the abdominal aorta:2

- Coeliac trunk: supplies liver, stomach, spleen, pancreas and proximal third of duodenum

- Superior mesenteric artery: supplies distal two-thirds of duodenum, jejunum, ileum, caecum, appendix, ascending colon and proximal third of the transverse colon

- Inferior mesenteric artery: supplies the distal half of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum and anus

The arterial supply of the digestive system is divided embryologically. The foregut is supplied by the coeliac trunk, the midgut by the superior mesenteric artery and the hindgut by the inferior mesenteric artery.

Venous drainage

The digestive system is drained by the portal venous system and the systemic venous system.1,2

Nutrient-rich blood is drained from the intestines by the hepatic portal vein to the liver, where it is filtered.

After processing by the liver, the blood is carried to the systemic system by hepatic veins, which then drain into the inferior vena cava.

Innervation

Swallowing and the anal sphincter are under somatic control. However, the rest of the tract is under autonomic control:2

- Sympathetic innervation is via the abdominopelvic splanchnic nerves and acts to inhibit peristalsis, contract anal sphincters, constrict blood vessels and redirect blood flow to skeletal muscles when needed.

- Parasympathetic innervation occurs via the vagus nerve and pelvic splanchnic nerves. This innervation acts to increase peristalsis, increase digestion, and relax the internal anal sphincter.

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Text references

- Moore, K.L., Dalley, A.F. and Agur, A.M., 2018. Clinically oriented anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.Vancouver

- Boron, W.F. and Boulpaep, E.L., 2016. Medical physiology E-book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Image references

- Figure 1. OpenStax College. Components of the Digestive System. License: [CC BY]