- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Leukaemia is a cancer of immature white blood cells and is the most common type of cancer in children, accounting for 31% of all childhood cancer cases.1

Aetiology

Leukaemia involves abnormal proliferation and differentiation of leucocytes or their precursor cells.

Most cases of leukaemia are caused by de novo mutations (new mutations which are not inherited). However, there are also genetic syndromes which predispose children to leukaemia.1

Certain chromosomal and genetic abnormalities can significantly affect prognosis and their presence or absence is now used to guide treatment.

Haematopoiesis and development of leukaemia

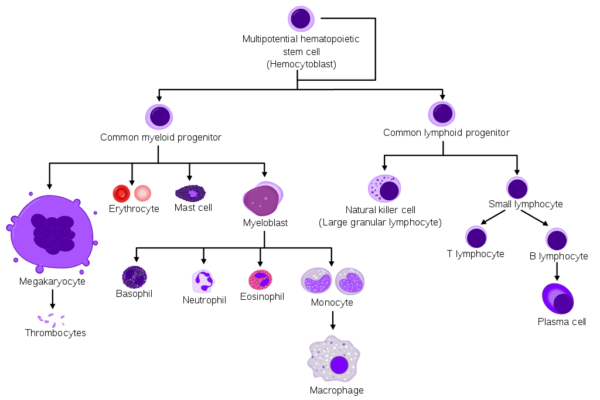

A multipotent haematopoietic stem cell can differentiate to give rise to either common lymphoid or myeloid progenitor cells (see figure 1). These progenitor cells differentiate further to produce their respective lymphoid or myeloid cell populations.

Acute leukaemias result from failure of lymphoid or myeloid progenitor cells to differentiate, with resultant uncontrolled proliferation of these immature blast cells.

Chronic leukaemias result from the uncontrolled proliferation of cells at a later stage of differentiation.

Leukaemia is categorised based up whether cells originate from lymphoid precursors (lymphocytic) or myeloid precursors (myelogenous), and by the degree of cell differentiation.

Acute leukaemias involve more immature cells (lymphoid or myeloid progenitor cells). Chronic leukaemias involve cells at a later stage of differentiation.

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)2

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is the most common type of leukaemia in children making up approximately 75% of childhood leukaemia diagnoses. It is most common in children aged 1 – 4 years.

ALL develops as a result of abnormal proliferation and failed differentiation of B or T lymphoid progenitor cells. The uncontrolled proliferation of these immature lymphocytes (lymphoblasts) within bone marrow prevents normal haematopoiesis, and the abnormal blasts can spread to infiltrate other organs.

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)3

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) makes up around 25% of diagnoses of childhood leukaemia.

AML results from uncontrolled proliferation and failed differentiation of immature blast cells of myeloid lineage. These blasts disrupt normal haematopoiesis in the bone marrow and can infiltrate extramedullary organs.

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)4

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) is less common in children (median age of diagnosis is 60-65 years). CML develops from blood cells of the myeloid lineage, which are more mature than those seen in AML. Use of cytogenetics has identified the Philadelphia chromosome as the cause of CML in more than 90% of cases, which results from a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22, t(9;22).

Patients can progress from the chronic phase to an accelerated phase, with an increase in immature blast cells. This is followed by further progression to a blast crisis phase, where there is ≥30% presence of blast cells in the bone marrow or peripheral blood (or extramedullary infiltration by blast cells).

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

In contrast to adults, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is extremely rare in children.

Risk factors

Genetic syndromes which predispose individuals leukaemia include:5,6,8,9

- Down’s syndrome: patients are 30 times more likely to develop ALL, and 150 times more likely to develop AML. The characteristic leukaemia seen in Down’s syndrome is M7 acute megakaryoblastic AML.

- Fanconi anaemia

- Li Fraumeni syndrome

- Ataxia telangiectasia

- Nijmegen breakage syndrome

Other risk factors include:1,6

- Exposure to ionising radiation

- Pesticides

- Viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Clinical features

Symptoms of leukaemia are often vague and non-specific and vary according to the age of the child.

Symptoms of generalised fatigue/malaise may progress to more specific symptoms of bone marrow failure.

History

Typical symptoms of leukaemia include:2-8,11

- Fatigue and malaise

- Bone and joint pain: particularly affecting the legs

- Dyspnoea: caused by anaemia, mediastinal mass or infection

- Dizziness and palpitations

- Recurrent and/or severe infections

- Fevers

- Thrombocytopenia: bleeding tendency (epistaxis, bleeding gums), easy bruising, rashes

Clinical examination

Typical clinical findings in leukaemia include:2-8,11

- Weight loss

- Skin: pallor, petechial rash, bruising

- Cardiovascular: tachycardia, flow murmur

- Abdomen: distension, hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly

- Lymphadenopathy

Uncommon clinical presentations

Uncommon clinical presentations of leukaemia include:2-8,11

- Central nervous system (CNS), due to infiltration of cerebrospinal fluid by blast cells: headache, irritability, papilloedema, nausea/vomiting, cranial nerve palsies.

- Testicular enlargement (1-2% males with new ALL diagnosis)11

- Leukaemia cutis (rare infiltration of the skin by leukaemia cells)

Red flag clinical features of suspected haematological malignancy in children (NICE)

The following red flag clinical features are suggestive of haematological malignancy in children.12,13

An urgent specialist assessment is required if any of the following red flag features are present:

- Unexplained petechiae

- Unexplained hepatosplenomegaly

An urgent full blood count is required if any of the following red flag features are present:

- Pallor

- Persistent fatigue

- Unexplained fever

- Unexplained persistent infection

- Generalised lymphadenopathy

- Unexplained bruising or bleeding

- Persistent/unexplained bone pain

Differential diagnoses

Table 1. The differential diagnoses of leukaemia.

|

Infective |

Malignant |

Autoimmune |

Haematological |

|

Infectious mononucleosis Parvovirus B19 Other viruses (flu, HIV, cytomegalovirus) Osteomyelitis

|

Lymphoma Rhabdomyosarcoma Other solid tumours

|

Systemic lupus erythematosus Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

|

Aplastic anaemia Fanconi anaemia Myelodysplasia Myelofibrosis Megaloblastic anaemia Lymphoproliferative disorders |

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:5,6

- Observations: fever can indicate malignancy or infection, and tachycardia can occur in infection or anaemia.

- Urine dip: infection is an important differential diagnosis.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): may show tachycardia, and a baseline is useful before cardiotoxic chemotherapy.

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:2-6,11

- Full blood count: blast cell proliferation causes raised white blood cell count, and pancytopenia will occur with bone marrow suppression (anaemia and thrombocytopenia are common, while white blood cell count may be variable).

- Blood film: shows the presence of blast cells (there may be a false negative if blasts are confined to bone marrow). Blast cells should normally not be seen in peripheral blood, so this is highly suspicious for leukaemia if seen on microscopy.10

- Coagulation profile: may be deranged or show disseminated intravascular coagulation.

- Baseline kidney and liver function: these are needed prior to starting chemotherapy. Liver tests may indicate liver infiltration, and electrolytes can show complications of very high cell turnover such as tumour lysis syndrome (although this is usually seen post-chemotherapy).

- Raised lactate dehydrogenase and uric acid: occur with increased cell turnover.

- Blood cultures: if presenting with fever/signs of infection.

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD): G6PD deficiency should be identified before commencing rasburicase as it can result in a haemolytic crisis.

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:2-6,11

- Chest X-ray: it is extremely important to identify early if a mediastinal mass is present before the child receives any anaesthetic. A mediastinal mass may be present in T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, which overlaps with T-cell ALL, and can cause airway compromise, cardiovascular collapse, and death. An X-ray may also show infection, enlarged nodes, and lytic bone lesions.

- Echocardiogram: prior to starting cardiotoxic chemotherapies.

Other investigations2-5,8,11

Bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy are used for both diagnosis and monitoring. A biopsy may be used for:

- Diagnosis (presence of ≥20% blasts)

- Minimal residual disease analysis after treatment (see below)

- Cytogenetics: detects chromosomal aberrations

- Immunophenotyping: uses flow cytometry analysis to characterise the leukaemia blasts

The use of cytogenetics and immunophenotyping is important for disease classification, and therefore risk stratification to guide treatment.

Cytogenetics detects chromosomal abnormalities and is used for risk stratification, by categorising children into three risk groups (low, intermediate and high). These are used to indicate prognosis and guide treatment. 5,8,9

A lumbar puncture may also be performed looking for the presence of leukaemic cells in cerebrospinal fluid.

Minimal residual disease

At the end of induction chemotherapy, the blast cell count should be ≤5% for patients to be classed as being in remission.

Presence of residual disease (i.e. persistent leukaemic cells) indicates the need for more intensive chemotherapy.

Classification of ALL and AML

The two most widely known classification systems for leukaemia are the French-American-British (FAB) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) classifications.

However, there is less emphasis on the use of classification systems in clinical practice, and they are not relied upon for risk stratification.

- French-American-British (FAB) classification is based on morphology (the appearance of cells under a microscope) and cytochemical staining of leukaemic cells.

- World Health Organisation (WHO) classification system uses cytogenetics (chromosomal analysis) and immunophenotyping (use of antibodies to detect white blood cell antigens).

Management

Chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment in leukaemia.

Acute lymphocytic leukaemia2,5,6,8,9

The stages of chemotherapy for ALL include:

- Induction: intensive phase lasting 4-6 weeks that aims to destroy all leukaemic blast cells. To reduce the risk of tumour lysis syndrome, pre-phase treatment with hydration and allopurinol/rasburicase is given prior to chemotherapy.

- Consolidation and CNS treatment: the aim is to maintain remission. Lumbar puncture with intrathecal methotrexate aims to prevent spread to the CNS.

- Delayed intensification: the aim is to remove as many remaining blasts as possible prior to the maintenance phase.

- Maintenance: treatment continues for 2 years in girls, and 3 years in boys. This can involve oral or intravenous chemotherapy, steroids, and intrathecal treatments.

Chemotherapy agents commonly used include corticosteroids, vincristine, anthracyclines, asparaginase, cyclophosphamide and cytarabine.

Acute myeloid leukaemia3,6

The stages of chemotherapy for AML include:

- Induction: intensive phase which aims to destroy all leukaemic cells.

- Post-remission treatment: usually involves two further courses of chemotherapy, aiming to destroy residual cells and prevent a recurrence.

Bone marrow tests are repeated following induction, to assess whether remission has been achieved.

Other treatments 2-6,8,9

Other treatments for leukaemia include:

- Bone marrow transplant: this is only used in patients with a high risk of disease recurrence, or with recurrence following standard chemotherapy.

- Testicular radiotherapy: used for patients with testicular infiltration.

- CNS treatments: chemotherapy drugs may be injected intrathecally (via lumbar puncture), and occasionally radiotherapy is used for infiltration following relapse.

Supportive measures 2-6,8,9

Other supportive measures for leukaemia include:

- Education for families: it is vital that children present quickly when they are unwell, particularly when febrile.

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics urgently for children presenting with suspected neutropenic sepsis.

- Prophylactic antimicrobials: particularly co-trimoxazole (to prevent pneumocystis jirovecii) in ALL, and antifungals in AML.

- Blood transfusions.

- Allopurinol (prevention of tumour lysis syndrome).

- Insertion of a central venous catheter for chemotherapy and blood sampling.

- Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF): to support cell counts (e.g. prolonged neutropenia).

- Psychosocial support, educational support, advice about financial support for families.

Complications

Early complications of leukaemia include: 5,6,11

- Neutropenic sepsis

- Thrombocytopenia: bleeding, stroke, haemorrhage (lung or gastrointestinal)

- Blast cell lysis

- Leucostasis: stroke, pulmonary oedema, heart failure

- CNS infiltration: seizures, stroke

Therapy-related complications of leukaemia include: 5,6

- Corticosteroid side effects: behavioural issues, weight gain

- Neutropenic sepsis

- Tumour lysis syndrome

- Mucositis, gastrointestinal inflammation

- Renal and hepatic toxicity

- Neurotoxicity

- Venous thromboembolism

- Alopecia

Long-term complications of leukaemia include:5,6

- Secondary cancers

- Avascular necrosis (a complication of high-dose steroids)

- Cardiotoxicity (e.g. secondary to anthracycline treatment)

- Reduced growth hormone: short stature and obesity

- Fertility issues

Tumour lysis syndrome11,14

Tumour lysis syndrome is an oncological emergency caused by lysis of tumour cells, either due to chemotherapy treatment or sometimes spontaneously in highly proliferative tumours.

It results in electrolyte imbalances including hyperphosphataemia, hyperkalaemia, hypocalcaemia, hyperuricaemia.

Clinical manifestations include:

- Acute kidney injury

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Nausea and vomiting

- Seizures.

Prophylactic hydration and allopurinol are important prior to chemotherapy. Rasburicase may be used if white cell count is >50, as this will actively break down the uric acid, while allopurinol prevents uric acid production.

Treatment involves aggressive hydration, rasburicase or allopurinol, and haemofiltration or dialysis.

G6PD deficiency should be excluded before giving rasburicase as it increases the risk of haemolytic crisis.

Prognosis

The prognosis in leukaemia has significantly improved over the past 40 years, with an increase in overall 5-year survival rate from 33% in 1971 to 79% in 2000.6

Improvements in survival, particularly in ALL, have resulted from effective optimisation of risk-directed therapy, and extensive involvement of clinical trials in treatment.

The overall cure rate in ALL is now 85-90%.15

In patients with disease recurrence, this usually happens within the first 3 years.2

The best prognosis is in children aged between 1 and 10 years.6

Key points

- Leukaemia is the most common malignancy in children, predominantly ALL and AML.

- Symptoms can be non-specific initially. A full blood count is a useful early investigation.

- Bone marrow biopsy is usually required for diagnosis and disease classification.

- Chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment.

- Bone marrow transplant is only used in patients with a high risk of disease recurrence, or with recurrence following standard chemotherapy.

- Prognosis is generally excellent in children.

- Neutropenic sepsis is a life-threatening complication during therapy; parents should know the importance of early presentation, and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started as soon as possible.

Reviewer

Dr Simon Bomken

MRC Clinician Scientist and Honorary Consultant Paediatric Oncologist

Wolfson Childhood Cancer Research Centre

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Types of childhood cancer. Available from: [LINK]

- Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). Available from: [LINK]

- Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK, authored by C.Tidy. Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML). Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK, authored by C. Tidy. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. May 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK, authored by C.Tidy. Childhood leukaemias. Sep 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Cancer Research UK. Acute myeloid leukaemia: types. Aug 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Terwilliger and M Abdul-Hay. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a comprehensive review and 2017 update. June 2017. Available from: [LINK]

- Pui et al. Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: Progress Through Collaboration. Sep 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Leukaemia Care. The link between Down’s syndrome and leukaemia. Available from: [LINK]

- Kar and N. Hijaya. Diagnosis and Initial Management of Paediatric Acute Leukaemia in the Emergency Department Setting. June 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). Haematological cancers: improving outcomes. NICE guideline NG47. Published May 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). Haematological cancers – recognition and referral. Nov 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Science Direct. Tumour lysis syndrome. Available from: [LINK]

- Vora et al. Treatment reduction for children and young adults with low-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia defined by minimal residual disease (UKALL 2003): a randomised controlled trial. Published Feb 2013. Available from: [LINK]

Figure 1. A. Rad & M. Häggström. Simplified Hematopoiesis. License: [CC-BY-SA]. Available from: [LINK]