- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Lymphoma is a group of malignancies which arise within the lymphatic system, which includes lymph nodes, the spleen, the thymus and the bone marrow.1

The two main types of lymphoma are Hodgkin’s lymphoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Lymphoma is the third most common cancer in childhood and accounts for 10% of new cancer cases in children.1,2

Lymphoma is more common in teenagers and young adults (15 – 24 years).2,3

Aetiology

Lymphoma results from genetic alterations which trigger the abnormal proliferation of lymphocytes.

Although the underlying cause of lymphoma is not known, chromosomal abnormalities have been identified which are associated with subtypes of lymphoma and can indicate prognosis.

One of the key features which distinguish most lymphomas from leukaemia is that the malignant cells are mature lymphocytes, and they arise within sites outside of the bone marrow (e.g. lymph nodes). In contrast, leukaemia develops from immature blasts and arises within the bone marrow.

The exceptions to this general rule are the less common lymphoblastic lymphomas (B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, and T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma), which develop from immature precursor lymphoblasts similarly to leukaemia.

The way in which lymphoblastic lymphomas are distinguished from lymphoblastic leukaemia is the degree of bone marrow infiltration by blasts; <25% bone marrow involvement is lymphoma, while >25% is leukaemia. However, these are treated the same as acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL).4

Classification

Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL)

Each year, approximately 70 children aged 0 – 14, 120 teenagers aged 15 – 19, and 180 young adults aged 20 – 24 are diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma.3

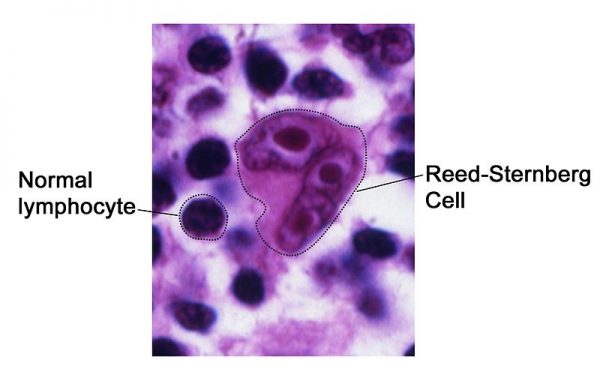

Hodgkin’s lymphoma is characterised histologically by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells (giant multinucleated cells), with associated smaller mononuclear cells, which arise from B lymphocytes.5-8

Table 1: Types of Hodgkin’s lymphoma.5-7

|

|

Type |

Features |

|

Classical HL (85% cases) |

Nodular sclerosis (70%) |

Lymph nodes contain scar tissue (sclerosis) Good prognosis |

|

Mixed cellularity (20-25%) |

Increased frequency in HIV/immunocompromised, EBV association |

|

|

Lymphocyte-rich (5%) |

Good prognosis Early presentation with peripheral adenopathy |

|

|

Lymphocyte-depleted (<1%) |

Aggressive HIV/immunocompromised, EBV association |

|

|

Non-classical HL |

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL (NLPHL) |

Reed-Sternberg cells are not present Slow growing but has a risk of transforming to high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL)

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma affects around 80 children per year and is more common in boys.9

The majority of cases are high-grade lymphomas, often of B-cell origin.10-11

B-cell NHL usually affects lymph nodes in the abdomen/gastrointestinal tract but can also develop in the head and neck, while T-cell NHL usually affects lymph nodes in the chest.10,12

Extranodal NHL develops in sites outside of the lymph nodes.

Table 1. Types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma categorised by cell type and grade. Lymphomas seen more commonly in paediatric patients are highlighted in bold (Burkitt’s, large B-cell, lymphoblastic, anaplastic), with their respective frequency.10,13

|

|

B-cell |

T-cell |

|

Mature cell: High-grade |

Burkitt’s lymphoma (50-60%) Large B-cell lymphomas* (10-15%) Primary CNS lymphomas |

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (10-12%) Peripheral T-cell lymphoma

|

|

Mature cell: Low-grade |

Follicular lymphoma Marginal zone lymphoma |

Mycosis fungoides and cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (very rarely seen) |

|

Precursor cell/lymphoblastic |

Precursor B-lymphoblastic lymphoma (5%) |

Precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (15%) |

*Large B-cell lymphomas include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma.

Risk factors

Risk factors for lymphoma include:

- Immunodeficiency: post-solid organ transplant (post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders), ataxia telangiectasia, Nijmegan-Breakage syndrome, HIV, and immunosuppressant drugs.3,5,7,10,12,13

- Epstein-Barr virus infection3,5,6-8

Clinical features

History

Patients commonly present with painless, progressive lymphadenopathy (develops over weeks-months).2,3,5-9,12-14

Infection is the most common cause of lymphadenopathy in children, so make sure to take a careful history which includes infective symptoms.

Other symptoms of lymphoma include: 2,3,5-9,12-14

- B symptoms: fatigue, drenching night sweats, fever >38oC, weight loss (>10% in 6 months).

- Pruritus

- Mediastinal involvement (thymus or mediastinal lymph nodes): dyspnoea, cough, chest pain.

The following symptoms indicate extranodal involvement, which is more common in NHL:13

- Bone marrow: symptoms of anaemia, infections, easy bruising/bleeding.

- Abdomen: bloating, early satiety, pain, unable to pass stools and vomiting if obstructed.

- Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy: urinary retention.

- Skin: new skin lesions (such as mycosis fungoides), or jaundice.

- Testicular swelling

- Central nervous system: behavioural change, headache, confusion, nausea and vomiting, seizures, weakness, sensory changes.

Clinical examination

Typical clinical findings in lymphoma include:

- Non-tender, firm, matted lymph nodes (more likely to be malignant)

- Hodgkin’s: often cervical, supraclavicular, axillary

- Non-Hodgkin’s: more rapidly growing bulky lymphadenopathy

- Mediastinal mass: may cause severe effects such as SVC obstruction, effusions, or airway obstruction

- Abdomen: splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, abdominal mass

- Skin: T cell lymphomas including mycosis fungoides, jaundice

- Testicular mass

- Neurological: weakness, sensory abnormalities, features of raised intracranial pressure

Differential diagnosis

Table 2. Differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy. 14

|

Infective (viral) |

Infective (bacterial) |

Other |

|

Common upper respiratory tract infections Infectious mononucleosis Rubella, measles Cytomegalovirus HIV HHV-6 Adenovirus

|

Tuberculosis Typhoid Syphilis Lyme disease Brucellosis

Protozoal Toxoplasmosis Leishmaniasis Trypanosomiasis |

Malignant Leukaemia Neuroblastoma

Autoimmune Juvenile idiopathic arthritis Systemic lupus erythematosus Drug reactions |

Infection is the most common cause of lymphadenopathy in children

Investigations

Bedside investigations

Relevant bedside investigations include:5,13

- Observations: fever can be caused by malignancy or infection, respiratory rate and SpO2 are important to assess for patients presenting with mediastinal disease.

- Swabs: identify any infective causes of lymphadenopathy

- Urine dip: exclude infection if febrile

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): chest disease may cause effects such as pericardial effusions and obtaining a baseline ECG is useful to have prior to starting cardiotoxic chemotherapies.

Laboratory investigations

Relevant laboratory investigations include:5,13

- Full blood count (FBC): may show pancytopenia or leukaemic presentation – leukaemia (important differential diagnosis) will cause anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and usually a raised WBC.

- Urea and electrolytes (U&E): baseline kidney function is important prior to starting chemotherapy, and electrolytes can show tumour lysis syndrome if rapid cell turnover occurs (but this is more common following chemotherapy).

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and urate: these indicate a high cell turnover when raised.

- Liver function tests (LFT): baseline liver function is important prior to starting chemotherapy, while derangement may indicate hepatic involvement. Low albumin is associated with a worse prognosis.

- Monospot test: exclude Epstein-Barr virus infection

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): if raised this is associated with worse prognosis

- Hepatitis B/HIV tests: risk of hepatitis reactivation with rituximab treatment

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD): G6PD deficiency should be identified before commencing rasburicase as it can cause a haemolytic crisis.

Imaging

Relevant imaging investigations include:5,13

- Chest X-ray: can show a mediastinal mass arising from the lymph nodes or thymus, intrathoracic lymph nodes, or effusions.

- CT/MRI/PET scans: for staging purposes

- Ultrasound of the liver and spleen

Biopsies3,5-9,12-14

Biopsy of the enlarged lymph node is used for diagnosis, usually under a general anaesthetic. Excision biopsy or a partial biopsy are used, as fine needle aspiration is insufficient. In Burkitt’s lymphoma, analysis of bone marrow or effusions can be an alternative method of diagnosis for very unwell children, reducing the need for general anaesthetic and biopsy.

Bone marrow biopsy can be used for staging purposes to detect infiltration and lumbar puncture is used to stage the cerebrospinal fluid.

Staging

An overview of the staging system for lymphoma is shown (simplified) in table 3, although the details of staging differ between Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s.

The Ann Arbor classification is often used for Hodgkin’s, while St Jude classification is used for non-Hodgkin’s, which has more extranodal involvement.3,5,7-10,12-13

Table 3. Simplified staging for lymphoma.

|

Stage |

Features |

|

I |

1 group of lymph nodes is affected on 1 side of the diaphragm |

|

II |

≥2 groups of lymph nodes are affected on 1 side of the diaphragm |

|

III |

Lymphoma is present in nodes on both sides of the diaphragm |

|

IV Hodgkin’s |

Involvement of extranodal sites beyond those designated by ‘E’ (below) |

|

IV Non-Hodgkin’s |

Disseminated/multifocal involvement of ≥1 extralymphatic site OR isolated extralymphatic organ involvement with distant node involvement |

|

Letters are used to denote other details in staging: A: no systemic symptoms B: systemic symptoms present: weight loss/fever/night sweats E: involvement of single, contiguous, or proximal extranodal site (Hodgkin’s) |

|

Management

Hodgkin’s lymphoma3,5,7,8

Chemotherapy is the main treatment used for Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Other management options for Hodkin’s lymphoma include:

- Radiotherapy is used in <50% children. A PET scan is used to assess response after 2 cycles of chemotherapy, and patients with ongoing PET avidity will receive adjuvant radiotherapy.

- Lymphocyte-predominant HL has less intensive treatment (due to a slower growth rate); usually surgery or low-dose chemotherapy is sufficient.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma9-13

Chemotherapy is the main treatment used for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The specific regimen will be based on the type of disease and staging, but generally, B-cell NHL will have 4-6 courses of intensive chemotherapy, while T-cell NHL will have less intensive chemotherapy that lasts 2-3 years. Intrathecal chemotherapy is used as prophylaxis/treatment of CNS lymphoma.

Other management options for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma include:

- Biologics: Rituximab (anti CD20 antibody) is the standard of care in high-risk mature B-cell NHL.

- Radiotherapy is used rarely in addition to chemotherapy.

- Bone marrow transplant (BMT): high dose chemotherapy with BMT can be used for relapsed patients.

- Lymphoblastic lymphoma is treated according to chemotherapy protocols for ALL.

Complications

Table 4. Long-term and short-term complications of lymphoma and treatments.5,7,8,12-13

|

|

Condition-related |

Treatment-related |

|

Short-term |

Superior vena cava obstruction Bowel obstruction/perforation Cytopenias Pericardial or pleural effusions Pain from tumour invasion Tumour lysis syndrome |

Mucositis, diarrhoea Anorexia and weight loss Alopecia Nausea and vomiting Fatigue Tumour lysis syndrome |

|

Long-term |

|

Secondary cancers Cardiotoxicity Pulmonary toxicity Renal impairment Growth impairment Infertility |

Tumour lysis syndrome10,13

Tumour lysis syndrome is an oncological emergency caused by lysis of tumour cells, either due to chemotherapy treatment or sometimes spontaneously in highly proliferative tumours.

It results in electrolyte imbalances including hyperphosphataemia, hyperkalaemia, hypocalcaemia, hyperuricaemia.

Clinical manifestations include:

- Acute kidney injury

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Nausea and vomiting

- Seizures.

Prophylactic hydration and allopurinol are important prior to chemotherapy. Rasburicase may be used if white cell count is >50, as this will actively break down the uric acid, while allopurinol prevents uric acid production.

Treatment involves aggressive hydration, rasburicase or allopurinol, and haemofiltration or dialysis.

G6PD deficiency should be excluded before giving rasburicase as it increases the risk of haemolytic crisis.

Prognosis

Approximately 90% of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and >90% of children with Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma achieve remission.3,9

However, excellent survival rates mean that the long-term effects of treatment can be significant. Children require long-term follow-up, assessing for recurrence and the onset of any late side effects.

Key points

- The two main types of lymphoma are Hodgkin’s lymphoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which each have their own subtypes.

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma is characterised by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells and is derived from B lymphocytes.

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are classified by whether T or B lymphocytes are involved, whether the disease is high or low grade, and includes the lymphoblastic lymphomas that are similar to ALL.

- Progressive, painless lymphadenopathy is the most common clinical presentation.

- Chemotherapy is the main treatment used, sometimes with radiotherapy, biological therapy, and bone marrow transplant for relapse.

- Prognosis is good but treatment is very intensive and long-term side effects of therapy can be significant.

Reviewer

Dr Simon Bomken

MRC Clinician Scientist and Honorary Consultant Paediatric Oncologist

Wolfson Childhood Cancer Research Centre

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Lymphoma. Available from: [LINK]

- Lymphoma Action. Lymphoma in Children. November 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Hodgkin Lymphoma. August 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Boston Children’s Hospital. Lymphoblastic lymphoma. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK. Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. May 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Wang et al. Diagnosis of Hodgkin Lymphoma in the Modern Era. January 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Shanbhag and Ambinder. Hodgkin Lymphoma: a review and update on recent progress. March 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Children with Cancer UK. Hodgkin Lymphoma. Available from: [LINK]

- Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. December 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Minard-Colin et al. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in Children and Adolescents: Progress Through Effective Collaboration, Current Knowledge, and Challenges Ahead. September 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Sandlund and Martin. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma across the paediatric and adolescent and young adult age spectrum. December 2016. Available from: [LINK]

- Children with Cancer UK. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. December 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK. Generalised Lymphadenopathy. March 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Radiopaedia. Mediastinal Lymphoma. Available from: [LINK]

- Science Direct. Tumour lysis syndrome. Available from: [LINK]

Figure 1. National Cancer Institute. Reed-Sternberg Cell. License: [Public domain]. Available from: [LINK]