- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

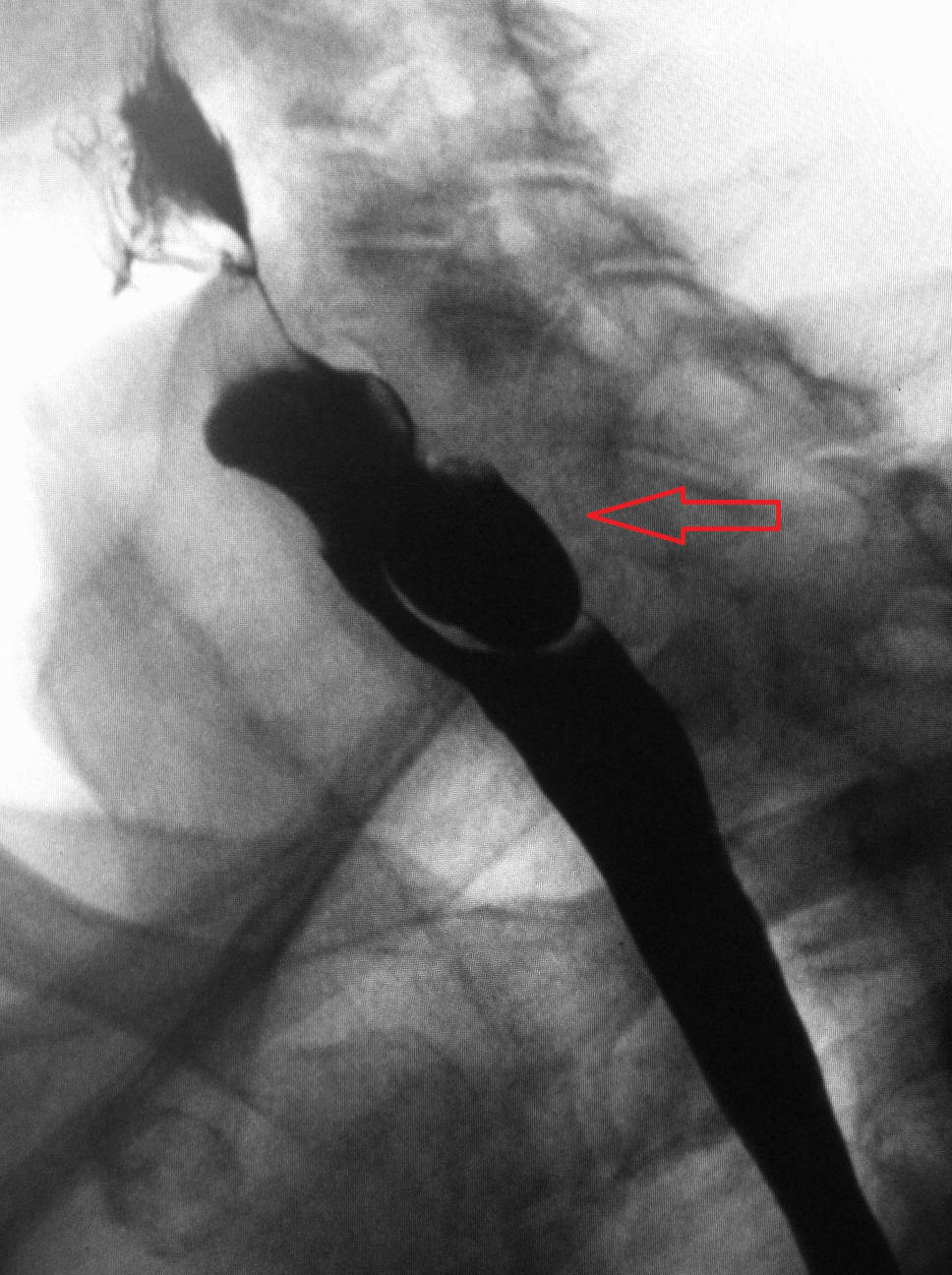

A pharyngeal pouch is a herniation of the posterior pharyngeal wall through its muscular walls. It commonly presents in elderly patients with symptoms of difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) and regurgitation, leading to aspiration, chronic cough and weight loss.

In the UK, the annual incidence is estimated to be 2 in 100,000.1

Aetiology

Anatomy

Also known as Zenker’s diverticulum, a pharyngeal pouch describes herniation of the pharynx through an area of weakness known as Killian’s dehiscence in the posterior pharyngeal wall.

This triangular area of weakness is bounded superiorly by the oblique fibres of the thyropharyngeus (inferior constrictor muscles), and inferiorly by the transverse fibres of the cricopharyngeus muscle.1

Pathophysiology

There are several theories as to why pharyngeal pouches occur. Some theories suggest it may be due to reduced elasticity of the cricopharyngeus, resulting in a higher pressure exerted on Killian’s triangle during swallowing. This repeated pressure then leads to the formation of a diverticulum.

Other theories suggest the ageing process leads to generally reduced elasticity of the pharyngeal muscles, or that patients develop increased upper oesophageal tone.2

Risk factors

Risk factors for a pharyngeal pouch include:3

- Male sex (2:1 ratio)

- Increasing age

Clinical features

Patients with symptomatic and untreated pharyngeal pouch suffer the consequences of dysphagia and repeated aspiration, as well as those of retained medication.

Risks also include fistulation into the trachea, vocal cord paralysis due to pressure of the sac and squamous cell carcinoma of the diverticulum itself.4

History

Typical symptoms of a pharyngeal pouch include:

- Dysphagia and choking, described as food getting ‘stuck’

- A gurgling feeling on swallowing

- Regurgitation

- Halitosis

- Neck lump

Patients with established dysphagia may also present with weight loss. It is important to ask the patient if they have had recurrent chest infections, as this may indicate repeated aspiration from the pouch into the airways.

Clinical examination

If a pharyngeal pouch is suspected, patients should undergo a thorough neck examination.

Large pharyngeal pouches may be palpated as a gurgling mass on the neck, though this is a rare finding. In the ENT clinic setting, a flexible nasendoscopy should be performed to exclude laryngeal malignancy as a potential cause of dysphagia.

Differential diagnoses

Other causes of dysphagia should be considered, such as achalasia, strictures of the upper aerodigestive tract, and malignancy.

Other causes of a neck lump include (but are not limited) to lymphadenopathy (reactive, infective or malignant), cutaneous cysts and branchial cysts. These would be investigated via ultrasound +/- fine needle aspiration in the first instance to classify them.

Investigations

Imaging is key to the definitive diagnosis of a pharyngeal pouch. Laboratory investigations may show electrolyte abnormalities secondary to malnutrition.

The gold imaging standard is fluoroscopy, and pharyngeal pouches are best visualised with a barium swallow. They appear as an outpouching of the posterior wall at the junction of the pharynx and oesophagus.

Ultrasound scanning is a suitable alternative for those with swallowing difficulties or if barium is not tolerated.5

Management

Conservative management

Patients with asymptomatic pouches measuring <1cm can be managed conservatively.

Surgical management

A surgical approach is required in symptomatic patients, and these involve trans-oral (endoscopic) or open percutaneous surgery.

A trans-oral approach is made more difficult by the following factors:

- Patient factors: short neck, small chin, large body habitus, poor mouth opening

- Pharyngeal pouch factors: large pouch (>2cm), poor support of the pharyngeal pouch against the posterior wall

The trans-oral approach is less invasive than open surgery and tends to carry shorter operation times. Patients resume oral intake faster, leave hospital quicker and have fewer complications. However, the risk of recurrence is increased.6

The trans-oral approach involves rigid endoscopy with a Weerda diverticuloscope under general anaesthetic. The septum between the oesophagus and the pouch is divided with electrocautery, laser or staples.7

The open surgical approach is commonly a cricopharyngeal myotomy (whereby the cricopharyngeus muscle is divided) with resection of the pharyngeal pouch.7

Complications

Complications of the pharyngeal pouch itself include:1

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Ulceration of the pouch

- Fistulation between the pouch and trachea

- Vocal cord palsy due to pressure of pouch contents

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the pouch

Complications of surgical repair include:1

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve damage

- Perforation of the pouch or oesophagus

- Mediastinitis

- Pharyngeal fistula

- Pharyngeal or oesophageal stricture

- Recurrence

Key points

- Pharyngeal pouches are a herniation of the posterior pharyngeal wall through Killian’s dehiscence

- This triangle is bounded by thyropharyngeus superiorly and cricopharyngeus inferiorly

- Patients tend to be elderly and present with halitosis, dysphagia and regurgitation

- The key investigation is a barium swallow

- Definitive management is surgical in symptomatic or large pouches, and this can be either trans-oral or open surgery

- Risks of leaving a pharyngeal pouch untreated include aspiration pneumonia, ulceration of the pouch, fistulation between nearby structures and vocal cord palsy

Reviewer

Mr Mustafa Jaafar

ENT Registrar (North London Deanery)

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Text references

- Siddiq, M. A., S. Sood, and D. Strachan. ‘Pharyngeal Pouch (Zenker’s Diverticulum)’. Postgraduate Medical Journal 77, no. 910 (1 August 2001): 506–11.

- Cook, Ian J., Mary Gabb, Voula Panagopoulos, Glyn G. Jamieson, Wylie J. Dodds, John Dent, and David J. Shearman. ‘Pharyngeal (Zenker’s) Diverticulum Is a Disorder of Upper Esophageal Sphincter Opening’. Gastroenterology 103, no. 4 (October 1992): 1229–35

- Lixin, Jiang, Hu Bing, Wang Zhigang, and Zhao Binghui. ‘Sonographic Diagnosis Features of Zenker Diverticulum’. European Journal of Radiology 80, no. 2 (November 2011): e13-19

- Kensing, K. P., J. G. White, F. Korompai, and W. P. Dyck. ‘Massive Bleeding from a Zenker’s Diverticulum: Case Report and Review of the Literature’. Southern Medical Journal 87, no. 10 (October 1994): 1003–4.

- Albers, Débora V., André Kondo, Wanderley M. Bernardo, Paulo Sakai, Renata Nobre Moura, Gustavo Luis Rodela Silva, Edson Ide, Toshiro Tomishige, and Eduardo G. H. de Moura. ‘Endoscopic versus Surgical Approach in the Treatment of Zenker’s Diverticulum: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’. Endoscopy International Open 4, no. 6 (June 2016): E678-686.

- Overbeek, J. J. van, P. E. Hoeksema, and E. T. Edens. ‘Microendoscopic Surgery of the Hypopharyngeal Diverticulum Using Electrocoagulation or Carbon Dioxide Laser’. The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 93, no. 1 Pt 1 (February 1984): 34–36.

- Gagic, N. M. ‘Cricopharyngeal Myotomy’. Canadian Journal of Surgery. Journal Canadien De Chirurgie 26, no. 1 (January 1983): 47–49.

Image references

- Figure 1. James Heilman, MD. Lateral X-ray of a Zenker’s diverticula. License: [CC BY-SA]