- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

An aneurysm is defined as a focal dilatation of an artery, with the largest diameter measuring more than 50% of the normal vessel diameter. The normal diameter of the popliteal artery varies from 0.7 to 1.1 cm.1

Popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) is the most common peripheral aneurysm (70-80%) and rarely occurs in isolation.2,3

The exact incidence of PAA is unknown, however, they are significantly more common in men, and incidence is likely to increase with age.3,4

PAAs are bilateral in around 50% of cases and have a strong association with the presence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). Around 40% of patients with a popliteal artery aneurysm have a AAA though only 10-15% of patients with a AAA also have a PAA.1,5

Aetiology

Anatomy

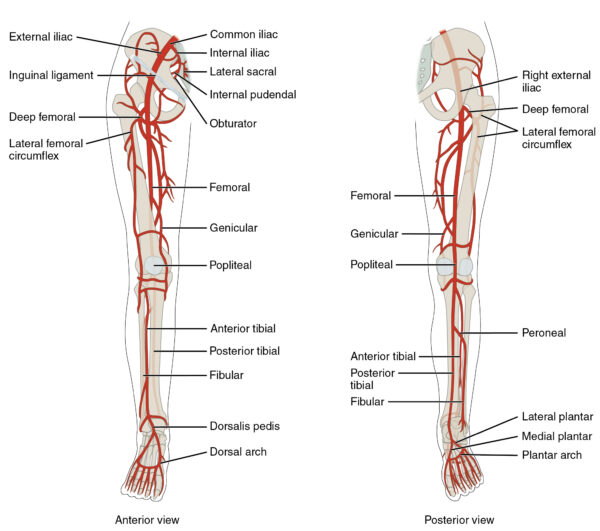

The main artery of the lower limb is the femoral artery, which is a continuation of the external iliac artery. The external iliac becomes the common femoral artery (CFA) when it crosses under the inguinal ligament and enters the femoral triangle.6,19

In the femoral triangle, the profunda femoris artery arises. This gives off three main branches, which supply muscles in the medial, posterior, and lateral thigh, as well as the neck and head of the femur.19

After giving off the profunda femoris branch the CFA continues as the superficial femoral artery (SFA) through the thigh. During its descent, it supplies the anterior thigh muscles.19

The SFA enters the adductor canal exiting at the adductor hiatus where it becomes the popliteal artery.1,6

The popliteal artery passes through the popliteal fossa terminating in the anterior tibial artery and tibioperoneal trunk. In turn, the tibioperoneal trunk divides into the posterior tibial and fibular (or peroneal) arteries:1,6,19

- Anterior tibial artery: passes anteriorly between the tibia and fibula. Runs down the length of the leg and into the foot, where it becomes the dorsalis pedis artery.

- Posterior tibial artery: continues inferiorly in the deep posterior compartment of the leg. Enters the foot via the tarsal tunnel.

- Fibular artery: descends posterior to the fibula, within the posterior compartment. Supplies muscles in the lateral compartment of the leg.

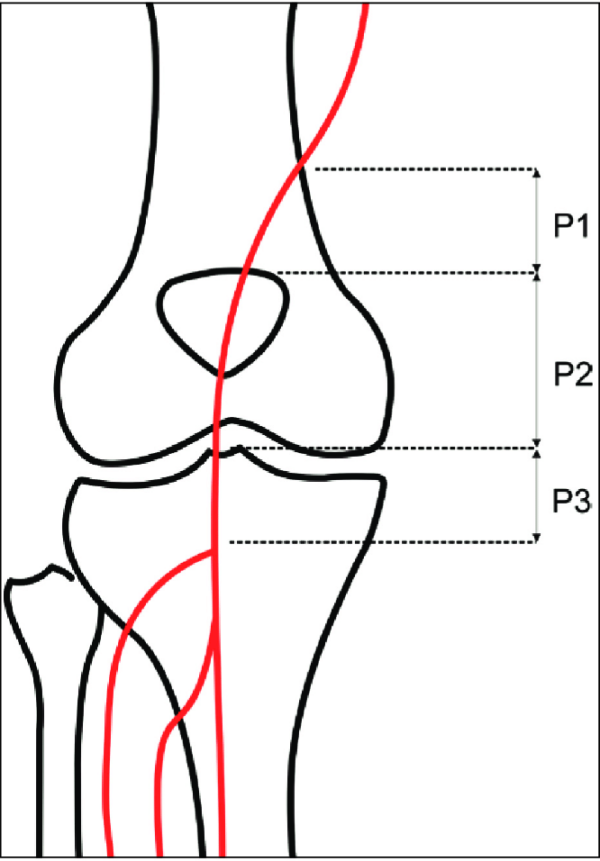

Surgically, the popliteal artery is divided into three segments (Figure 1):

- P1: adductor hiatus to the upper border of the patella

- P2: upper border of patella to the joint line

- P3: joint line to the emergence of anterior tibial artery

Popliteal fossa

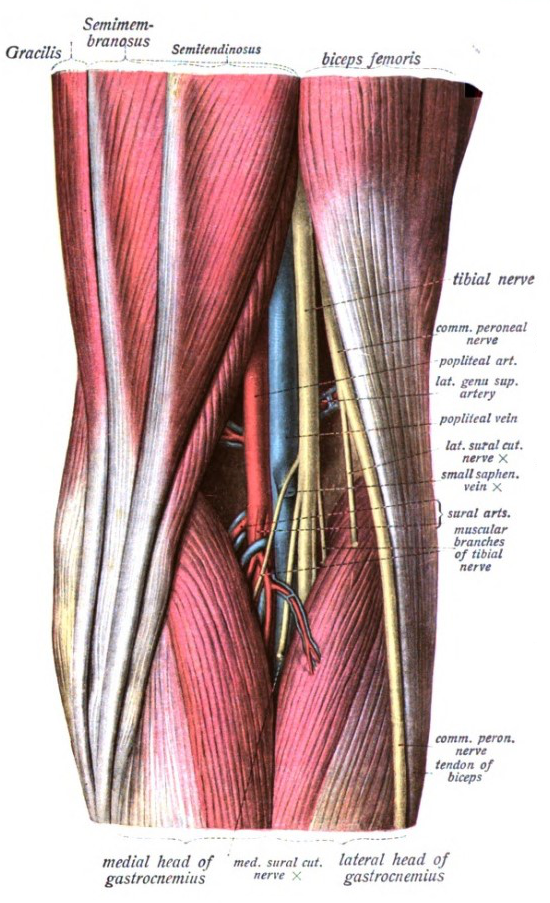

The popliteal fossa is a diamond-shaped area located on the posterior aspect of the knee.9,19

The borders of the popliteal fossa are as follows:19

- Superomedial border: semimembranosus

- Superolateral border: biceps femoris

- Inferomedial border: medial head of the gastrocnemius

- Inferolateral border: lateral head of the gastrocnemius and plantaris

The floor of the popliteal fossa is formed by the posterior femur and posterior surface of the knee joint capsule and popliteus. The roof is made up of the popliteal fascia and skin.19

The popliteal fossa is the main conduit for neurovascular structures entering and leaving the lower leg. Its contents include:19

- Popliteal artery

- Popliteal vein

- Tibial nerve

- Common fibular nerve

- Lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels

The deepest structure within the popliteal fossa is the popliteal artery.19

Risk factors

Like AAAs, the majority of PAAs develop secondary to atherosclerosis with the major risk factors including:1,2

- Smoking

- Hypertension

- Hyperlipidaemia

Additional risk factors for PAA include:1,2,3,5

- Increasing age

- Male gender: PAA affects men in 95% of cases

- Connective tissue disease: such as Marfan’s disease

- Family history

Clinical features

History

PAA may present symptomatically but is usually detected incidentally. Rupture of popliteal artery aneurysms is rare.2,5

Due to altered blood flow dynamics within the vessel, PAA predisposes patients to the formation of thrombus within the aneurysm. This can lead to acute limb ischaemia (ALI) secondary to complete aneurysm thrombosis and/or distal embolisation.1,5

A concerning presentation is a more gradual onset of intermittent claudication or chronic limb-threatening ischaemia (CLTI). These presentations occur due to gradual and progressive embolisation of thrombus from within the aneurysm which slowly accumulates within the tibial vessels and can be challenging to manage surgically.1

Less commonly, patients present with symptoms related to compression of surrounding structures in the popliteal fossa:2,9,11

- Tibial nerve: leg pain, weakness or absent plantarflexion, paraesthesia of the foot and posterolateral leg

- Popliteal vein: calf swelling

Definitions

Intermittent claudication: diminished circulation leads to pain in the lower limb on walking or exercise that is relieved by rest.12

Chronic limb-threatening ischaemia: defined by ischaemic rest pain, with or without tissue loss (for example ulcers, gangrene, or infection). Characterised by chronic inadequate tissue perfusion at rest.12

Clinical examination

Popliteal artery aneurysms can often be detected on clinical examination, with a palpable pulsatile mass at the level of the knee joint.1

Both popliteal fossae should be examined bilaterally with the knees in a semi-flexed position. For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to peripheral vascular examination.

Acute limb ischaemia

ALI is defined as “any sudden decrease in limb perfusion causing a potential threat to limb viability”. Signs and symptoms develop over less than 2 weeks. ALI is a surgical emergency associated with a significant risk of mortality and limb loss.13,14

Classical signs and symptoms of ALI are summarised as the six P’s:12

- Pain

- Pallor

- Pulselessness

- Perishingly cold (poikilothermia)

- Paraesthesia

- Paralysis

Patients usually describe an acute onset of pain, loss of function/inability to stand, and then develop foot numbness.

Classical signs of ALI may not be present in patients with pre-existing peripheral vascular disease due to the presence of collateral vessels.13

The Rutherford classification can be used to classify patients with acute limb ischaemia.15 This classification describes the viability of a limb, which is important to guide surgical management decisions.

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to acute limb ischaemia.

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses for a popliteal swelling include:1,5

- Popliteal cyst (commonly known as Baker’s cyst)

- Lymphadenopathy

- Cystic adventitial disease of the popliteal artery

It is important to consider PAA in all cases of acute limb ischaemia.

Investigations

The selection of appropriate investigations is dependent on the mode of presentation, either elective or emergency.

Elective presentation

The diagnostic investigation of choice for a suspected popliteal aneurysm is an ultrasound duplex scan. This allows for:2

- differentiation between other causes of popliteal fossa swelling

- accurate assessment of aneurysm size

- recognition of signs of aneurysm thrombosis or embolisation

Additional cross-sectional imaging (CT or MR angiogram) is mandatory if surgical intervention is planned.2

Emergency presentation

See the Geeky Medics guide to acute limb ischaemia for more information on the initial investigations for patients presenting with an acutely ischaemic limb.

Patients presenting as an emergency require urgent cross-sectional imaging, either CT angiogram or MR angiogram.2,5

Imaging is necessary for the following reasons:

- Confirm the diagnosis

- Establish the aneurysm size

- Assess the vessels proximal and distal to the aneurysm: important in planning a surgical approach

- Assess for the presence of thrombus: thrombus within the aneurysm sac is an independent indication for surgical repair

As well as CTA or MRA, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) may be used intra-operatively to guide therapeutic interventions:16

- DSA is an invasive investigation which produces clear images of blood vessels in a variety of organ systems

- Iodinated contrast medium is injected whilst a series of x-ray images are taken, which are processed to produce the final images by a subtraction technique

Management

Management of popliteal aneurysms can be divided into symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

Non-surgical (conservative) management can be considered in all cases, irrespective of aneurysm size and presentation. Shared decision making between the patient and clinician is paramount to safe and effective management.

Asymptomatic patients

Intervention in asymptomatic patients may be recommended to reduce the risk of thromboembolic complications and associated risk of limb loss.3

Intervention is usually recommended in asymptomatic patients with a popliteal aneurysm ≥ 20mm. However, repair should be considered at any size if there is thrombus within the aneurysm sac or evidence of emboli in the vessels distal to the aneurysm.2,3

Patients with an aneurysm <20mm and without thrombus can be enrolled in a programme of surveillance, usually with an annual clinical assessment and duplex ultrasound scan to monitor aneurysm size, thrombus formation, or embolisation.3

Patients should also be advised on appropriate lifestyle measures to reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease. Alongside this, medications such as an antiplatelet and statin should be considered, as well as diagnosis and appropriate management of diabetes.18

Aneurysm repair

Open surgical or endovascular options are available if repair is considered.2

Open repair involves surgical exclusion of the popliteal aneurysm. If the aneurysm is anatomically suitable it can be repaired from a posterior approach ‘inlaying’ a graft into the popliteal artery. More commonly, a bypass graft is sewn onto the popliteal artery above and below the aneurysm, which is subsequently ligated:2,3,11

- Bypass grafts are either the patient’s own vein (most commonly great saphenous vein) or a prosthetic graft (such as PTFE)

- In patients who are fit enough an open repair is typically first-line

It is possible to repair a PAA endovascularly. A covered stent can be inserted across the aneurysm to exclude the aneurysm from circulation:1,2,3,11

- For this procedure to be appropriate, there must be normal calibre, healthy artery above and below the aneurysm for the stent to seal in

- Endovascular repair is more commonly recommended for high-risk surgical candidates, as this intervention can be performed under local anaesthesia

Following either open or endovascular aneurysm repair, patients require follow up with clinical examination and duplex ultrasound scan.3

Symptomatic patients

Due to the risk of limb loss, all patients with symptoms of thrombosis or distal embolisation should be considered for intervention, regardless of aneurysm size.2

The specific intervention that is recommended depends on the patient’s clinical presentation and the degree of arterial occlusion that has occurred.1 Patients with symptoms related to compression of surrounding structures should also be considered for intervention.

Acute limb ischaemia

Patients presenting with acute limb ischaemia (ALI) can be categorised using the Rutherford classification.15

ALI is a surgical emergency and requires urgent attention. Initial management for all patients presenting with ALI should include resuscitation, opiate analgesia and anticoagulation with intravenous heparin.13,14

Patients presenting with features of ALI must be referred to vascular surgery as an emergency. Assessment by a vascular specialist should consider the following questions:

- Is the limb salvageable? Is the ischaemia that has occurred reversible, and would revascularisation preserve the limb.

- How much time is available? Muscles typically survive 3-6 hours of ischaemia, after which permanent functional impairment or tissue loss develops rapidly.14

- Is the patient likely to survive revascularisation? Many patients are too physiologically unstable or frail to withstand the metabolic insult associated with revascularisation, in which case primary amputation is the safest option.

Considering the results of the investigations that have been performed, and ensuring the patient is counselled and consented as appropriate, a decision will be made regarding surgical revascularisation.

If surgical revascularisation is planned, the aim of surgical intervention is to restore blood supply to the ischaemic limb and exclude the aneurysm from the circulation. A range of open and endovascular techniques are available, and hybrid operations (both open surgery and endovascular intervention) are common.

Patients with patent distal (run-off) vessels can be managed with an open surgical bypass. However, if the run-off vessels are occluded by an embolus, this may need retrieval to increase the likelihood of successful surgical intervention. Options to improve distal circulation include:3

- Open balloon embolectomy: Fogarty catheter

- Endovascular techniques: catheter suction thrombectomy or mechanical devices to aspirate thrombus

- Catheter-directed thrombolysis

In patients with irreversible ischaemia (Rutherford Grade III) palliative care or primary amputation can be considered.3

Fasciotomy

Four quadrant lower limb fasciotomy may be necessary for all patients with ALI who undergo revascularisation due to the risk of compartment syndrome.3

Complications

The primary complication associated with popliteal artery aneurysm is distal thromboembolisation and the associated risk of limb loss.3

Other complications include pressure effects on surrounding structures, namely the popliteal vein and tibial nerve, or aneurysm rupture (though this is rare).5

Key points

- A popliteal artery aneurysm is defined as a focal dilatation in the artery, with the largest diameter measuring more than 50% of the normal vessel diameter.

- PAA is the most common peripheral aneurysm and is more common in males, and patients with an AAA.

- The popliteal artery is the deepest structure within the popliteal fossa and is closely related to the popliteal vein and tibial nerve.

- PAA may be detected asymptomatically, or present acutely with acute limb ischaemia related to thrombosis and/or distal embolisation.

- Investigations include a duplex ultrasound scan and/or CT angiogram.

- Elective aneurysm repair may be either open (more common) or endovascular.

- Patients presenting with acute limb ischaemia require urgent referral to vascular surgery.

- Patients presenting with acute limb ischaemia may be managed with thrombolysis and/or thrombectomy, urgent definitive aneurysm repair alongside thrombolytic therapy, or primary amputation, depending on their clinical presentation.

- The primary complication associated with PAA is distal thromboembolisation and the associated risk of limb loss.

Reviewer

Mr Craig Nesbitt

Consultant Vascular Surgeon

Northern Vascular Centre, Freeman Hospital

Newcastle Upon Tyne

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Kassem M, Gonzalez L. Popliteal Artery Aneurysm. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- MSD Manual. Peripheral Arterial Anuerysms. 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Farber A, Angle N, Avgerinos E, Dubois L, Eslami M, Geraghty P, Haurani M, Jim J, Ketteler E, Pulli R, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines on popliteal artery aneurysms. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2021.

- Radiopaedia. Popliteal artery aneurysm. 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- Souza D, Ashraf A. Popliteal artery aneurysm. 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- OpenStax. Circulatory Pathways. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Osawa Rodrigues T, Metzger P, Rossi F, Moreira S, Saleh M, Izukawa N, Almeida B, Kambara A. Outcomes of the Use of a Superflexible Nitinol Stent in the Popliteal Artery. Revista Brasileira de Cardiologia Invasiva (English Version). 2014;18.

- OpenStax College. Lower Limb Arteries Anterior Posterior. License: [CC BY]

- OpenStax. Appendicular Muscles of the Pelvic Girdle and Lower Limbs. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Dr Sobotta J. An anatomical illustration from Sobotta’s Human Anatomy 1908. License: [Public domain]

- Joshi D, Gupta Y, Ganai B, Mortensen C. Endovascular versus open repair of asymptomatic popliteal artery aneurysm. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2019;12:CD010149-CD010149.

- NICE CKS. Peripheral arterial disease. 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Darwood R. Acute Limb Ischaemia. 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- GeekyMedics. Acute Limb Ischaemia. 2020. Available from: [LINK]

- Hardman R, Jazaeri O, Yi J, Smith M, Gupta R. Overview of Classification Systems in Peripheral Artery Disease. Seminars in Interventional Radiology. 2014;31:378-388.

- Glick Y, El-Feky M. Digital subtraction angiography. 2022. Available from: [LINK]

- Wikimedia Commons. Cerebral Angiogram obtained using an iodine based contrast medium. 2007. License: [Public domain]

- NICE. Peripheral arterial disease. 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- Moore KL, Dalley II AF, Agur AMR. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Wolter Kluwer; 2018.