- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Taking a detailed history is important, but it is equally important to be able to communicate the information you gather effectively and efficiently.

Presenting a history in a structured and clear way is a valuable skill for OSCEs and clinical practice.

Depending on the situation, presentations can last anywhere from a few minutes (much like an SBAR) to more than 10 minutes for complex patients with new presentations. However, the approach to these presentations is similar – they aim to convey full, pertinent information to a listener unfamiliar with the patient.

This guide provides a step-by-step approach to presenting a history, including an example patient presentation.

Tips for presenting a history

Confidence

Confidence is key when presenting a history, especially in an OSCE setting. The person receiving the information wants to trust that you are sure of the information you have gathered.

Speak clearly and loudly enough to be understood by colleagues.

Using notes

If you took notes during your consultation, feel free to refer to them, but try not to read them straight off the page, concise notes don’t always translate to an effective presentation.

It can be tempting to say all the information you have gathered when reading from notes, but remember that you should have a reason for each sentence within the presentation.

Time management

Be aware of how much time you have to ensure you communicate all the relevant information.

This is especially important in an OSCE setting, where the time may be limited (e.g. 1 – 2 minutes). In this situation, it is important to prioritise the most relevant information which has led you to your differential/working diagnosis and management plan.

Be honest

Never guess or report false positives/negatives in the patient presentation.

If you are unsure, say so and why, rather than implying something without being certain or giving the implication of normality, especially if you omitted part of an examination.

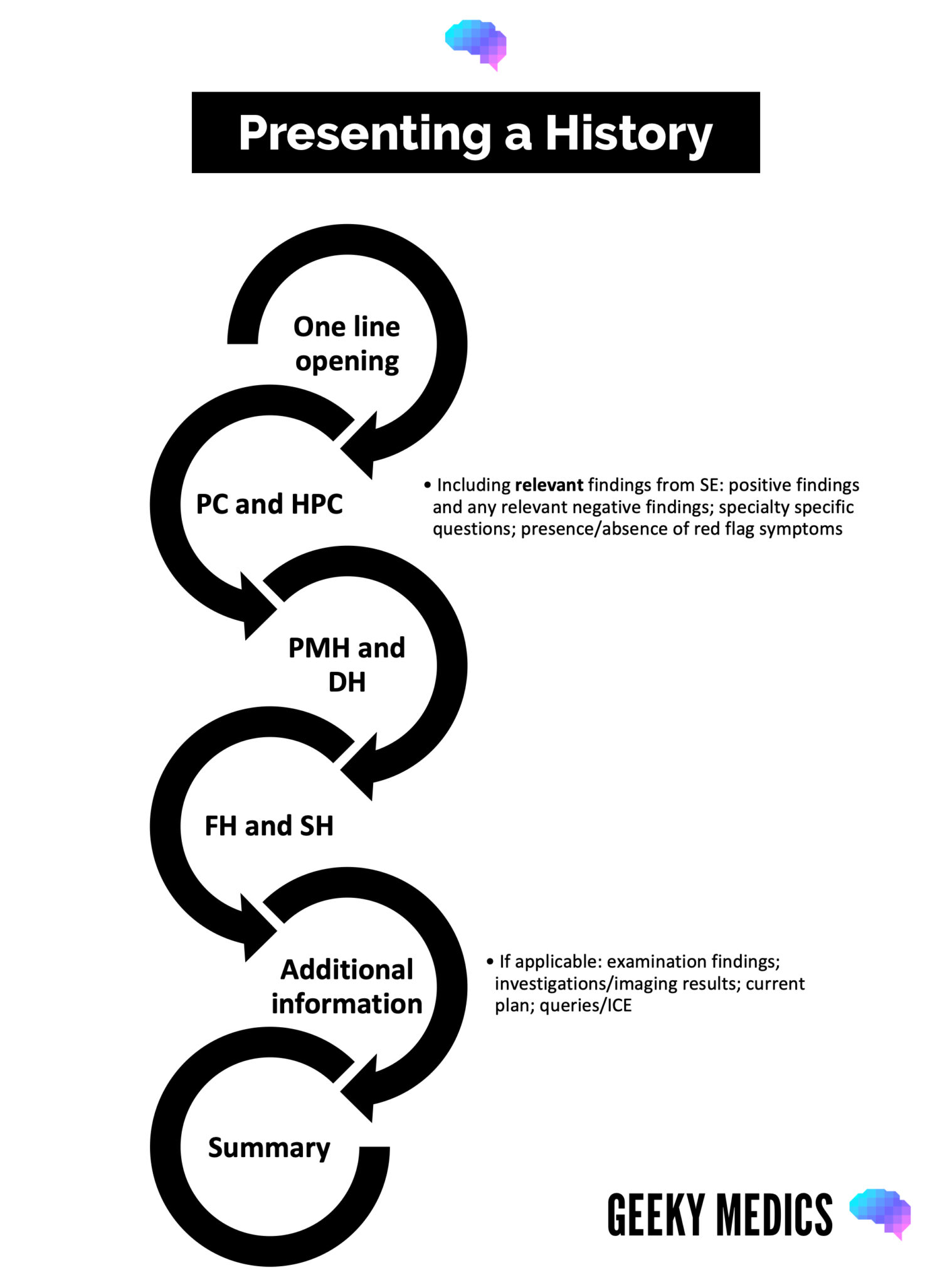

Structuring the presentation

Opening

This should be a brief one-line summary containing the patient’s name, age, presenting complaint and key past medical history.

The presenting complaint is often why the patient sought medical attention initially and should form the basis for further details you report in the presentation: “Mrs Smith is a 66-year-old woman presenting with right-sided hip pain on a background of osteoarthritis”.

If the patient is presenting as a follow-up visit to outpatients and does not have a presenting complaint, you can include other relevant details (e.g. reason for attendance or referral): “Mrs Smith is a 58-year-old woman presenting to clinic for follow-up of ongoing loose stool and bloating without obvious cause.”

History of presenting complaint

For any patients presenting with pain, briefly recap SOCRATES. For example:

- S: Right hip pain

- O: Started 18 months ago, has been getting worse

- C: Dull ache

- R: Radiates to groin and lateral aspect of the thigh

- A: Can get knee pain occasionally but not recently

- T: Occurs when standing for long periods

- E: Painkillers not helping, sitting sometimes helps, strenuous activity makes it worse

- S: Pain is 4/10 in clinic today, can get to 9/10 at worst

“The dull ache in her right hip has worsened over the past 18 months, radiating to her groin and lateral thigh. There are no significant associated features, the pain is worse on movement and standing, easing at rest. Severity ranges from 4-9/10.”

For any patient presenting with system-specific symptoms, group their symptoms together: “Diarrhoea started 3 weeks ago with no obvious trigger. No pain, blood or mucous. Passing stool 3 times per day at 6 on Bristol stool chart. Bloating occurs 1 hour after meals and is uncomfortable but not painful. No recent changes to diet.”

Other important positive and negative findings

At this stage, it is important to highlight any positive or negative findings which can rule out a likely pathology, a more sinister cause, or an emergency.

Avoid listing all negative findings, but any positive findings should be reported. These include red flag symptoms, specialty-specific pathologies, relevant systemic enquiry findings and other symptoms which may influence management.

Commenting on how the patient feels generally is appropriate here. Although systemic enquiry normally occurs at the end when taking a history, any relevant symptoms can be presented here: “Mrs Smith did not describe any unintentional weight loss, fevers, night sweats, or recent trauma. She is otherwise systemically well.”

Past medical history

To aid memory, the past medical history can be divided into:

- Conditions relevant to the presenting complaint

- Chronic conditions and how well they are being managed

- Surgical history

- Past hospitalisations

Not all procedures will be relevant to the presenting complaint (in this example, Mrs Smith’s appendicectomy in 1986), but it is important to report any complications, especially if the patient is being considered for a surgical pathway: “She was diagnosed with left hip osteoarthritis in 2016, largely asymptomatic since a left hip replacement in 2018; a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in 2019, managed by diet; nothing else of significance.”

Drug history

Listing all current medications may not be appropriate, especially for more complex patients. If this list is long, highlight important medications (e.g. takes X for Y condition). Important medications that patients are not taking should also be included.

For example, if a patient is being considered for surgery, it is important to know if they are on anticoagulants, as these will need to be stopped before surgery. Or, if a patient is presenting with infective symptoms, their condition may be exacerbated if they are on long-term steroids (e.g. rheumatological conditions) or immunosuppressants (e.g. transplant patients).

Additionally, medications with a high prevalence of interactions, such as anti-psychotics, would be relevant if symptoms may be due to a medication interaction or the patient may require a new medication to be prescribed.

Always remember to mention allergies and symptoms experienced when they encounter allergens.

For example, “She takes naproxen 500mg once daily, omeprazole 20mg once daily, and an over-the-counter multivitamin. Not on steroids, blood thinners or bisphosphates. No known allergies.”

Family history

Patients may have an extensive family history of various conditions. It is important to report any conditions relevant to the presenting complaint. For example, in a hip fracture, a family history of Perthe’s disease would be relevant, but a family history of diabetes in a patient with known diabetes would be less relevant: “Family history significant for one brother with Perthe’s disease and her father had bilateral hip replacement by age 65. Nothing else of note.”

Family history may be more important in certain situations. For example, if a genetic condition is suspected in a paediatric patient.

Social history

An overview of how the patient normally performs activities of daily living (AoDL) is helpful, rather than a complete report on their daily activities. This allows care plans to aim for the patient to resume normal or improved function after discharge. It is important to mention if the patient is dependent or independent at home, especially following an inpatient stay.

Other relevant details include occupation, alcohol intake, smoking history and specialty-specific information (e.g. a travel history in patients with infective symptoms or religion if providing medications with animal products or blood transfusions).

For example, “Before this episode of pain, she mobilised independently but is currently finding it difficult to navigate stairs at home. She lives with her husband and works as a school secretary; her work is unaffected by the pain. She has never smoked and only drinks alcohol socially.”

Examination findings

If incorporating examination findings into a presentation, positive and relevant negative findings should be provided rather than recounting the whole examination.

Providing the NEWS score and stating which observations are abnormal is good practice. This is especially important for sick patients.

Provide an overview of the stages of the examination:

- General inspection: do they appear well? Any notable findings?

- Close inspection: any positive features of disease?

- Avoid reporting findings as ‘normal’, instead report the findings (e.g. abdomen soft and non-tender, adequate range of active and passive movement)

- Report relevant positive and negative findings relevant to the presenting complaint (e.g. no added crackles or wheeze on auscultation, anterior drawer test positive)

For example, “Mrs Smith appears in pain at rest, NEWS score 0. No obvious abnormalities on close inspection, pain on active movement and globally reduced range of movement in the right hip. No pain or restriction in the left hip. No concerning features on examination of knees and spine. Straight leg raises negative bilaterally.”

Investigations

If the patient has any recent, relevant investigation findings, providing a brief statement to summarise these can add to the overall picture of the patient and prevent the repetition of unnecessary investigations. Also, if the patient has had these investigations completed previously, it is helpful to state how long the time between results is and any changes that have occurred.

For inpatient presentations, it may be appropriate to mention investigations which have been requested but not yet undertaken (e.g. imaging).

For example, “Routine bloods show a microcytic anaemia. The most recent X-ray shows left hip replacement and narrowing of joint space in the right hip, which has not progressed significantly since the previous X-ray 6 months ago”.

Summary

Recap the opening line of the presentation to close. If required, state your overall impression of the patient and any differential diagnoses you have at this stage, with relevant supporting information.

State your plan. Are there any further examinations, investigations, or information you want to gather? This can include contacting other departments for input and contacting relatives/care homes for a collateral history.

If you have any questions for your senior at this stage, you can ask what their recommendations are or if there is anything they wish to clarify.

“In summary, this is a 58-year-old lady presenting with an 18-month history of worsening right-sided hip pain on a background of osteoarthritis and type 2 diabetes, with no red flag symptoms or concerning features. Primary differential diagnosis of pain related to progressing osteoarthritis, no current concerns about hip fracture or infection, although important to rule out muscle strain and sciatica.”

Example patient presentation

The following example patient presentation takes approximately 2 minutes but covers all the salient points and provides an overview of the patient.

“Mrs Smith is a 66-year-old lady presenting with right-sided hip pain on a background of osteoarthritis.

The dull ache in her right hip has worsened over the past 18 months, radiating to her groin and lateral thigh. There are no significant associated features. The pain is worse on movement and standing, easing at rest. Severity ranges from 4-9/10.

Mrs Smith did not describe any unintentional weight loss, fevers, night sweats, or recent trauma. She is otherwise systemically well.

She was diagnosed with left hip osteoarthritis in 2016, largely asymptomatic since a left hip replacement in 2018; diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in 2019, managed by diet; nothing else of significance.

She takes naproxen 500mg once daily, omeprazole 20mg once daily, and an over-the-counter multivitamin. Not on steroids, blood thinners or bisphosphates. No known allergies.

Family history significant for one brother with Perthe’s disease and her father had bilateral hip replacement by age 65. Nothing else of note.

Before this episode of pain, she mobilised independently but is currently finding it difficult to navigate stairs at home. She lives with her husband and works as a school secretary; her work is unaffected by the pain. She has never smoked and only drinks alcohol socially.

Mrs Smith appears in pain at rest, NEWS score 0. No obvious abnormalities on close inspection, pain on active movement and globally reduced range of movement in the right hip. No pain or restriction in the left hip. No concerning features on examination of knees and spine. Straight leg raise negative bilaterally.

Routine bloods reveal a microcytic anaemia. The most recent x-ray shows left hip replacement and narrowing of joint space in the right hip, which has not progressed significantly since previous x-ray 6 months ago.

In summary, this is a 58-year-old lady presenting with an 18-month history of worsening right-sided hip pain on a background of osteoarthritis and type 2 diabetes, with no red flag symptoms or concerning features. Primary differential diagnosis of progressing osteoarthritis, no current concerns about hip fracture or infection, although important to rule out muscle strain and sciatica.”

Important points by specialty

Some points in a patient presentation may be more relevant depending on their presenting complaint and the medical specialty involved in their care or the referral.

These can be based on common conditions which are easily excluded, red flags which must not be missed, and other features which influence patient management. Most features listed can be described with a simple ‘present/absent’ description.

This is not an exhaustive list but is designed to illustrate the differences in presenting a history depending on the clinical context.

Table 1. Key patient presentation points by specialty.

| Specialty | Points to cover | Reasoning |

|

Any |

Fever, night sweats, weight loss, blood in sputum/vomit /urine/stool |

Common symptoms of malignancy and/or sepsis |

|

Cardiology |

Hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, chronic kidney disease Breathlessness, ankle swelling |

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease Suggestive of heart failure |

|

Respiratory |

Smoking, travel history, allergies, atopy, pets, occupation |

All can cause different respiratory diseases with similar presentations |

|

Gastrointestinal |

Changes in bowel habit, travel history, recent medication changes (e.g. aspirin, opioids), red flags (dysphagia/weight loss), alcohol use |

Eliminating any infectious causes and approximating the location of the problem within the GI tract is always useful |

|

Paediatrics |

Coryzal symptoms, work of breathing, milestones, social services involvement, behaviour changes, prenatal/birth/neonatal complications |

Describing an overview of any potential safeguarding issues at the outset of the presentation. Eliminating any common or congenital cause for presentation. |

|

Dermatology |

Travel history, significant sun exposure, pacemaker, atopy, immunosuppression, occupation |

Assessing patient’s risk factors for developing skin lesions. Also, to assess suitability for procedures to remove any lesions. |

|

Orthopaedics |

Hand dominance, weight-bearing, occupation, gait, anaesthetic history, blood thinners |

How impactful is the injury on their day-to-day life? Any history of surgical complications or current medications at risk of causing significant intra-operative bleeding. |

|

Ophthalmology |

Autoimmune conditions, atopy, diabetes, hypertension, driving, use of glasses/contact lenses |

Establishing if there are any underlying conditions which need treatment to resolve the eye symptoms. Safety regarding day-to-day activities. |

|

Neurology |

Visual disturbance, reduced /loss of consciousness, trauma, driving, occupation |

Assessing if the patient is acutely unwell or safe to discharge. |

Reviewers

1. Consultant in Intensive Care Medicine

2. Dr Jess Speller | Junior doctor

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

- Gleadle, J. (2011). History and Clinical Examination at a Glance. John Wiley & Sons.

- Fortin, A. H., Dwamena, F. C., Frankel, R. M., & Smith, R. C. (2012). Smith’s patient-centered interviewing: an evidence-based method. McGraw Hill Professional.