- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Prostate cancer causes significant morbidity around the world. In the UK, there are approximately 48, 500 new prostate cancer cases diagnosed annually.1 This represents 25% of all new male cancer cases, making prostate cancer the most common malignancy among men.1 Despite its’ prevalence, patients with prostate cancer have a demonstrated five-year survival rate of 98%.2

Anatomy

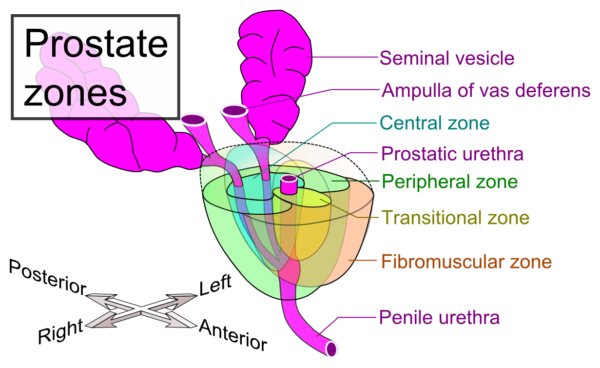

The prostate gland is a walnut-sized gland located between the bladder neck and the external urethral sphincter. The prostatic urethra runs directly through the prostate, emerging as the membranous and penile urethra. There are four main zones in the prostate gland- the peripheral zone (posteriorly), the fibromuscular zone (anteriorly), the central zone (centrally) and the transitional zone (surrounding the urethra) (Figure 1). The inferior portion of the prostate gland is termed the apex. Close relations to the prostate gland include the pubic symphysis (anteriorly), the rectum (posteriorly), the external urethral sphincter (inferiorly) and levator ani (laterally)- these are important to consider in the context of cancer metastases.3

The prostate gland is supplied by the inferior vesical (primary), middle rectal and internal pudendal arteries. The prostatic plexus directs venous drainage to the internal iliac veins. Lymphatic fluid is drained by the internal iliac and sacral lymph nodes. Finally, the prostate gland is innervated sympathetically by the hypogastric nerve and parasympathetically via the pelvic nerve.3

Risk factors

Key risk factors for the development of prostate cancer include: 5,6

- Age >50

- Black ethnicity

- Family history of prostate cancer

- Family history of other heritable cancers e.g. breast or colorectal cancer

- High levels of dietary fat

Clinical features

History

Symptoms

The majority of prostate cancer cases are diagnosed when still in the asymptomatic stage, and are often picked up through an elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test.2

The most common presenting symptoms of prostate cancer include:

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) including frequency, urgency, nocturia, hesitancy, dysuria and post-void dribbling.

Other symptoms can include:

- Haematuria

- Haematospermia

- Systemic symptoms: weight loss, weakness, fatigue

- Bone pain (associated with metastatic prostate cancer)

Other important areas to cover in the history include:

- Past medical history: previous hospitalisations, surgical procedures and history of pelvic radiation.

- Medication history

- Family history: prostate cancer in a first-degree relative less than 65 years old5 and breast cancer (BRCA2 gene is associated with prostate cancer).

- Social history: alcohol intake, smoking history (affects prostate cancer prognosis) and recreational drug use.

Clinical examination

In the context of suspected prostate cancer, a digital rectal examination (DRE) is necessary.*

Typical clinical findings on examination include:

- Asymmetrical prostate

- Nodular prostate

- Indurated prostate

*DRE may only detect tumours that are present in the posterior and lateral aspects of the prostate gland as these are often the only palpable regions; therefore DRE should always be accompanied by a PSA test (more below).2 Conversely, there will be patients with prostate cancer who have normal PSA levels and an abnormal DRE. It is, therefore, crucial that both are performed in suspected cases.

Differential diagnoses

LUTS are common in older men, therefore it can be challenging to differentiate between benign and malignant conditions of the urinary tract. For the purposes of this article, we present differentials for an elevated PSA test, including key distinguishing features (Table 1).6,2

Table 1. Differential diagnoses of an elevated PSA in older men

| Differential | Differentiating features |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) |

|

| Chronic prostatitis |

|

| Urethral instrumentation |

|

*A trick for distinguishing between benign and malignant-feeling conditions: soft, firm and hard consistencies equate to skin on the lips, the tip of the nose, and the forehead, respectively.

Investigations

Patients with suspected prostate cancer should undergo a series of laboratory and imaging tests to investigate further.6,2

Laboratory

Serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

Normal PSA levels are age-specific. In the UK, Public Health England recommends 2-week referral for men aged 50-69 years old with a PSA ≥3ng/ml and for men aged 70+ with a PSA >5ng/ml.7

Note: PSA can be raised by prostatitis, BPH or UTI, leading to a higher baseline. Therefore, it may be important to repeat the PSA to confirm trending elevation.

U&Es

Cancer may be obstructing ureters, leading to hydronephrosis and kidney dysfunction.

FBC

Anaemia

Other laboratory tests

The following are lab tests to be performed specifically in patients whereby androgen deprivation may be a future treatment option (more below):

- Testosterone levels

- LFTs: due to the risk of hepatitis with treatment

Imaging

Depending on PSA and lab results, multiparametric MRI may be warranted. MRI results are reported on a 5-point Likert scale. Biopsy is recommended for patients with a score of 3+.* There are a variety of different types of prostate biopsies, including:8

- Template transperineal biopsy, under general anaesthetic

- Transperineal biopsy, under local anaesthetic

- Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided needle biopsy

- MRI-TRUS fusion-guided needle biopsy

- TRUS cognitive-targeted

- Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) PET scan is most sensitive for detecting recurrent disease9

To investigate potential metastases, the following imaging may be indicated:

- DEXA bone scan- for bone metastases

- CT chest, abdomen, pelvis for visceral metastases

- PSMA PET scan is good for detecting metastases, in patients with low PSA levels

*Biopsy is important to ascertain the grade of prostate cancer. The Gleason grading system is a widely-adopted tool used to classify the histological differentiation of cancer and correlates strongly with prognosis.10 The Gleason score is calculated by adding the two most prevalent differentiation patterns together (i.e. 3 grade most common + 4 grade second most common).

The International Society of Urologic Pathologists (ISUP) has translated the Gleason score into five stages of graded correlates (Table 2).

Table 2. ISUP grading system for prostate cancer, incorporating the Gleason score10

| Gleason score | Tumour grade | Clinical significance |

| ≤6 | 1 | Low-grade tumour, sometimes “clinically insignificant” |

| 7 (3+4) | 2 | Intermediate-grade tumour. More favourable outcome than 4+3 |

| 7 (4+3) | 3 | Intermediate-grade tumour. Less favourable outcome than 3+4 |

| 8 | 4 | High-grade tumour |

| 9-10 | 5 | Highest grade tumour |

In addition to tumour grade, it is valuable to stage prostate cancer using the TNM staging system.

Prostate cancer screening

Prostate cancer screening is controversial for several reasons. Those in favour of PSA screening often cite research that denotes modest reductions in mortality; while critics argue that the relative indolent nature of disease coupled with overdiagnosis and unnecessary investigations create harm for patients.11 At present, there is no formal screening program for prostate cancer in the UK. However, men >50 years old are eligible to request a PSA test, following discussions with their GP about the pros and cons.12

Management

The approach to managing prostate cancer is heavily dependent on the patient’s risk group, projected survival and personal wishes. Patient’s may be stratified into risk groups (e.g. low, intermediate, high risk) and 10-year survival may be predicted based on G8 and Mini-COG instruments.6 Depending on the risk group, a variety of management strategies may be followed:13

Low risk

Low risk = PSA <10ng/ml + Gleason score ≤6 + clinical stage T1-2a

Watchful waiting (non-intentional for curative treatment)

In a joint discussion between patient and provider, men may opt to undergo watchful waiting. This means that they will undergo no treatment; however, will generally have regular DRE examinations and PSA tests. Should there be a significant change in symptoms or PSA levels, palliative care may be initiated, depending on the patient’s wishes. Used if Gleason score 2-4 at any age OR score 5-6 in the elderly/unfit with life expectancy less than 10 years.

Active surveillance (intent for curative treatment, but delayed)

In men who undergo active surveillance, regular DRE, PSA tests and often prostate biopsies (no more than annually), are performed. Should there be a significant change in any of the above findings, active treatment (hormonal, radiotherapy, surgery) may be initiated, depending on the patient’s wishes.

Intermediate risk

Intermediate risk = PSA 10-20ng/ml OR Gleason score 7 OR T2b stage

Active surveillance

For men with intermediate risk, or those who refuse active treatment.

Surgery

Radical prostatectomy: total removal of the prostate through open, laparoscopic or robotic-assisted approaches. Used for T1-T3 tumours in patients with a life expectancy of greater than 10 years.

Radiotherapy

External-beam radiotherapy (EBRT): beams of radiation are targeted to cancer cells in the prostate. Therapy is typically given for 7-8 weeks. Used for T1-3 tumours.

Brachytherapy: an innovative form of radiotherapy for prostate cancer, brachytherapy involves the permanent implantation of small balls of radioactive material into the prostate gland. Radiation is constantly provided in order to shrink tumour cells. Used for localised T1-2 tumours with a Gleason score of 7, PSA <20ng/ml and life expectancy greater than 5 years.

High risk

High risk = PSA >20ng/ml OR Gleason score 8-10 OR ≥ T2c stage

Active surveillance

For men who refuse active treatment.

Surgery

Radical prostatectomy: total removal of the prostate through open, laparoscopic or robotic-assisted approaches. Used for T1-T3 tumours and in patients with a life expectancy of greater than 10 years.

Radiotherapy

External-beam radiotherapy (EBRT): beams of radiation are targeted to cancer cells in the prostate. Used for T1-3 tumours.

Parallel hormone therapy may be considered as an adjuvant to radiotherapy, or on its’ own for metastatic disease Strategies include:

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) therapy: GnRH antagonists competitively bind GnRH receptors in the anterior pituitary, resulting in a decrease in testosterone. GnRH agonists active GnRH receptors over a prolonged period of time, leading to desensitization and decreased androgen secretion. Starving the prostate of androgens will result in shrinkage of the gland and the associated malignancy.

- Androgen receptor antagonists (e.g. bicalutamide, flutamide): this class of medication blocks cancerous androgen receptors, leading to decreased androgen-driven malignant growth.

- Androgen blockers targeting the adrenal glands: androgens are also formed in the adrenal glands and can be blocked from release using medications such as abiraterone and ketoconazole.

- Bilateral orchiectomy: removal of the testicles starves the prostate gland of testosterone.

- Oestrogen therapy: not frequently used anymore. Oestrogen therapy inhibits GnRH via negative feedback, decreasing testosterone levels. Side effects include breast enlargement and venous thromboembolism.

Side effects of hormone therapy include hot flushes, decreased bone density, fractures, low libido, erectile dysfunction, altered lipids and more. These are important to discuss with patients, in consideration of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer.

Complications

Treatment complications of radical treatment for prostate cancer include:6

- Dysuria

- Urinary frequency

- Urinary incontinence

- Rectal bleeding/proctitis (mainly associated with radiotherapy)

- Erectile dysfunction (may be caused by surgery or androgen deprivation therapy)

Prognosis

Prostate cancer is a highly curable cancer, with a five-year survival rate of ~98%.2 However, patients may incur significant morbidity due to treatment regimens, including persistent dysuria, urinary frequency, erectile dysfunction, rectal bleeding and incontinence.

References

- Cancer Research UK. Prostate cancer statistics. Published in 2017. [LINK]

- Taplin, Mary-Ellen; Philip W Kantoff; Smith J. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of prostate cancer. Published in 2019.[LINK]

- Singh, Omesh; Bolla Rao S. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Prostate. Published in 2020. [LINK]

- Haggstrom M. Prostate Zones. Published in 2019. [LINK]

- Sartor AO. Risk factors for prostate cancer. Published in 2020. [LINK]

- Wallace, Timothy; Anscher M. Prostate cancer. Published in 2020. [LINK]

- Prostate cancer risk management programme (PCRMP): benefits and risks of PSA testing. Published in 2016. [LINK]

- Frydenberg M, Stricker PD, Kaye KW. Prostate cancer diagnosis and management. Published in 2019. [LINK]

- Hoffman MJ. Current Developments in the Management of Prostate Cancer The Timing of Molecular Imaging in Prostate Cancer. Published in 2018. [LINK]

- Yang X. Interpretation of prostate biopsy. Published in 2019. [LINK]

- Tikkinen KAO, Dahm P, Lytvyn L, et al. Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: A clinical practice guideline. Published in 2018. [LINK]

- NHS. PSA testing. [LINK]

- Bhatt, Nikita; Manecksha, Rustom; Flynn R. Urology Handbook for Medical Students. Published in 2017. [LINK]

Reviewer

Nikita Bhatt

Urology SpR