- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Regional anaesthesia (RA) is a subspecialty in anaesthetics focusing on the local anaesthetic blockade of peripheral nerves and central neuraxis. Regional anaesthesia is widely used for perioperative and postoperative analgesia in modern anaesthetic practice and is a core skill set in anaesthetic training.

Regional techniques allow the patient to remain conscious during surgery and provide prolonged postoperative pain control.

Other advantages of regional anaesthesia include:

- Avoidance of adverse effects of general anaesthesia (e.g. nausea & vomiting, respiratory depression, risk of aspiration)

- Improved postoperative pain relief

- Decreased or no opioid use

- Faster recovery

- Reduces stress response to surgery

- Reduced blood loss

- Decreased incidence of postoperative pneumonia and venous thromboembolism

The minimum monitoring required during regional anaesthesia includes ECG, blood pressure and SpO2, which should begin before the procedure and continue for at least 30 minutes after the completion of the procedure.1

Types of regional anaesthesia include:2

- Central neuraxial blocks (CNB): placement of local anaesthetics around the nerves of the central nervous system and include spinal anaesthesia, epidural anaesthesia and caudal anaesthesia

- Peripheral nerve blocks (PNB): placement of local anaesthetic agents onto or near peripheral nerves

- Intravenous regional anaesthesia (IVRA): injection of local anaesthetic intravenously into an exsanguinated limb distal to an occluding tourniquet

- Topical and infiltration anaesthesia

This article will cover central neuraxial blocks (spinal, epidural and cauda) and peripheral nerve blocks.

Central neuraxial blocks (CNB)

The administration of central neuraxial anaesthesia should only be performed under strict aseptic conditions by trained staff with appropriate patient monitoring.

Patients are positioned sitting or in the lateral position for the CNB, and the choice between the positions depends on the provider, the patient, and the procedure.

Spinal and epidural needles are categorised by the design of their tips. Spinal needles may have a bevelled, cutting tip or a pencil-point, noncutting tip. Epidural needles are larger than spinal needles and have a curved tip to help guide the catheter in the epidural space.

A CNB can be performed either through a midline or a paramedian approach.

Spinal anaesthesia

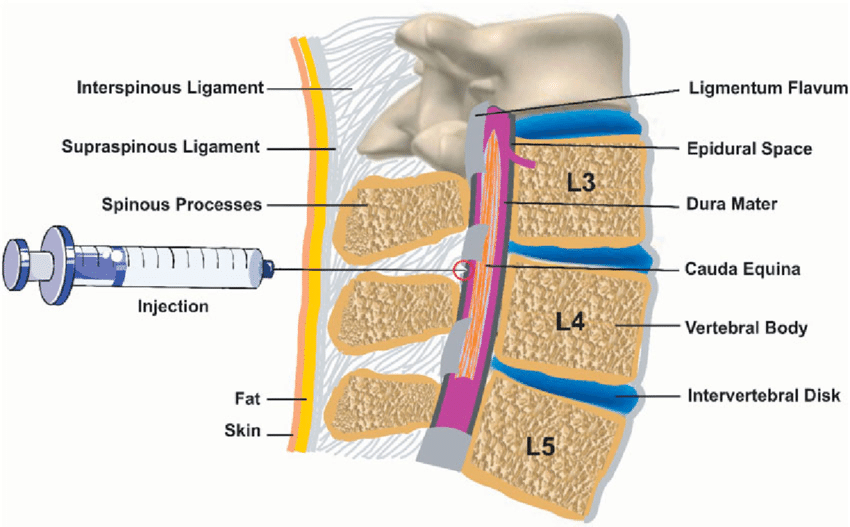

In spinal anaesthesia, a thin 9 cm needle is placed through the skin, soft tissue, spinal ligaments, and dura until it reaches the subarachnoid space and a small amount of local anaesthetic (specifically designed for subarachnoid space) is administered. The subarachnoid injection of a small dose of local anaesthetic can rapidly produce dense surgical anaesthesia.

Spinal anaesthesia is preferably performed in the lumbar region, below the termination of the spinal cord.

Spread and duration

The density and dose of the local anaesthetic medication determine the spread and duration of subarachnoid anaesthesia.

Local anaesthetics used for spinal anaesthesia are made hyperbaric (denser than CSF) by mixing them with dextrose. In contrast, plain local anaesthetic solutions are isobaric or slightly hypobaric. Hyperbaric solutions have greater spread in the direction of gravity and are more predictable with minimal inter-patient variability.

Intrathecal injection of local anaesthetics produces an extensive sympathetic block, leading to a drop in systemic vascular resistance and blood pressure. Heart rate may increase, decrease, or remain unchanged depending on the level of the block.

Spinal anaesthesia provides excellent operating conditions for lower abdominal, pelvic, and lower extremity surgery. Single-injection spinal anaesthesia only lasts up to two to three hours, making it unsuitable for prolonged surgeries.

Epidural anaesthesia

In epidural anaesthesia, a longer and larger needle is used to reach the epidural space, and a catheter is placed through that needle into the epidural space.

Epidural anaesthesia requires a larger volume of local anaesthetic and takes more time to establish. However, when a catheter is in the epidural space, a local anaesthetic can be injected repeatedly, and anaesthesia can be prolonged to match the duration of the surgery.

Spread and duration

The drug dose, injection site and patient variables are the main determinants of the spread of epidural block. The extent of the epidural block is proportional to the dose of local anaesthetic injected. The epidural injection can provide a segmental block.

Hypotension and bradycardia can occur during epidural anaesthesia, and the major risk factors for hypotension are the extent and onset of sensory block. Faster onset and more extensive block usually increase the probability of hypotension.3

Epidural can be safely performed in the lumbar, thoracic, and even cervical regions. A thoracic epidural is a useful adjunct to general anaesthesia for upper abdominal and thoracic surgery and provides intraoperative and postoperative pain management.

Metraminol, ephedrine and phenylephrine are the most commonly used vasopressors for managing hypotension associated with neuraxial anaesthesia.

Caudal anaesthesia

The caudal space is an extension of the epidural space. Caudal anaesthesia and analgesia are more useful in paediatric patients.

Complications

Complications of central neuraxial blocks include:

- Technical: failure of the technique

- Direct trauma to nerves and adjacent structures

- Haemodynamic instability and high block

- Post-dural puncture headache (PDPH)

- Meningitis

- Epidural haematoma/abscess

- Back pain

- Urinary retention

Peripheral nerve blocks

Peripheral nerves can be blocked at several points along their paths to provide site-specific, long-lasting, and effective anaesthesia and analgesia.

Local anaesthetic solution is injected as close to a nerve or network of nerves associated with the sensation of an area. A single injection or catheter can be used, depending on the indication of the peripheral nerve block.

Peripheral nerve blocks can be performed using a variety of guidance techniques. However, ultrasound guidance for regional anaesthesia has many advantages over other techniques as it allows direct imaging of peripheral nerves, the block needle tip, and injection distribution.

Peripheral nerve blocks can be used alone as the sole anaesthetic, as a supplement with general anaesthesia, or for providing prolonged postoperative analgesia.

Upper extremities

The nerve supply to the upper extremity is derived from the brachial plexus. Brachial plexus blocks above the clavicle target the ventral rami, trunks, and divisions. Brachial plexus blocks below the clavicle target the cords and terminal nerves.

An interscalene block is used for shoulder surgeries.

A supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary block are used for elbow, forearm, and hand operations.

Trunk blocks

Truncal fascial plane blocks involve the injection of a large volume of local anaesthetics into musculofascial planes that contain nerves rather than around specific nerves.4 An advantage of these blocks is that the injection is distant from critical structures such as the spinal cord, major vessels or pleura.

The erector spinae plane block, pectoral nerve block, and serratus anterior plane block are interfascial blocks used to provide surgical and postoperative analgesia to the chest wall.

The transversus abdominis plane block, rectus sheath block, ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks are interfascial plane blocks used to provide postoperative analgesia following abdominal surgeries.

The intercostal nerve block is mostly performed to provide analgesia following rib fractures and thoracic surgery.

Lower extremities

The nerve supply to the lower extremity is derived from the lumbar and sacral plexuses.

The femoral nerve block, fascia iliaca block, obturator nerve block, sciatic nerve block, popliteal nerve block and saphenous nerve block are the most common nerve blocks performed to provide surgical anaesthesia and postoperative analgesia.

Complications

Complications of peripheral nerve blocks include:

- Technical: failure of the technique

- Direct trauma to nerves and adjacent structures

- Drug-related: local anaesthetic systemic toxicity due to intravascular injection or systemic absorption, allergic reaction and methemoglobinemia (prilocaine)

- Infection

- Supraclavicular upper limb blocks: pneumothorax, ipsilateral phrenic nerve, and recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy

- Intercostal block: pneumothorax

- Femoral nerve block: vascular injury leading to haematoma and arterial pseudoaneurysm

Pharmacology of local anaesthetic drugs

Local anaesthetic drugs reversibly block sodium channels on the neuronal membrane and block the conduction of impulses, thus producing reversible loss of motor power and sensory sensation.

Local anaesthetics vary widely in their potency, duration of action, stability, solubility, and toxicity. Common local anaesthetics include lidocaine, bupivacaine, ropivacaine, levobupivacaine, and prilocaine.

Levobupivacaine, an isomer of bupivacaine, has anaesthetic and analgesic properties similar to bupivacaine but has fewer adverse effects.

Adrenaline is added to the local anaesthetic solutions to reduce the local blood flow, decrease drug uptake, and prolong the action.5 However, this should be avoided for blocks of the digits or penis due to the risk of tissue ischemia.

Table 1. Common local anaesthetics and their dosing.

| Structural classification | Onset of action | Maximum dose (without vasoconstrictor) | Maximum dose (with vasoconstrictor) | |

| Lidocaine | Amide | Fast | 3 mg/kg | 7 mg/kg |

| Bupivacaine | Amide | Moderate | 2 mg/kg | 2.5 mg/kg |

| Ropivacaine | Amide | Moderate | 3 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg |

| Levobupivacaine | Amide | Moderate | 2 mg/kg | 2.5 mg/kg |

Dosing for extreme body weight is calculated based on ideal body weight.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications to regional anaesthesia include:

- Patient refusal

- Localised infection

- Allergy to medications used

Relative contraindications to regional anaesthesia include:

- Abnormal anatomy

- Coagulation disorders

- Antiplatelets and anticoagulants

- Neurological disease

- Haemodynamic instability

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Text references

- Klein, A.A., Meek, T., Allcock, E., Cook, T.M., Mincher, N., Morris, C., Nimmo, A.F., Pandit, J.J., Pawa, A., Rodney, G. and Sheraton, T., 2021. Recommendations for standards of monitoring during anaesthesia and recovery 2021: Guideline from the Association of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia, 76(9), pp.1212-1223.

- New York School of Regional Anesthesia.Intravenous Regional Block for Upper and Lower Extremity Surgery. Available from: [LINK]

- Curatolo, M., Scaramozzino, P., Venuti, F.S., Orlando, A. and Zbinden, A.M., 1996. Factors associated with hypotension and bradycardia after epidural blockade. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 83(5), pp.1033-1040.

- Chin, K.J., Versyck, B. and Pawa, A., 2021. Ultrasound‐guided fascial plane blocks of the chest wall: a state‐of‐the‐art review. Anaesthesia, 76, pp.110-126.

- BNF. Treatment summary – local anaesthesia. Available from: [LINK]

Image references

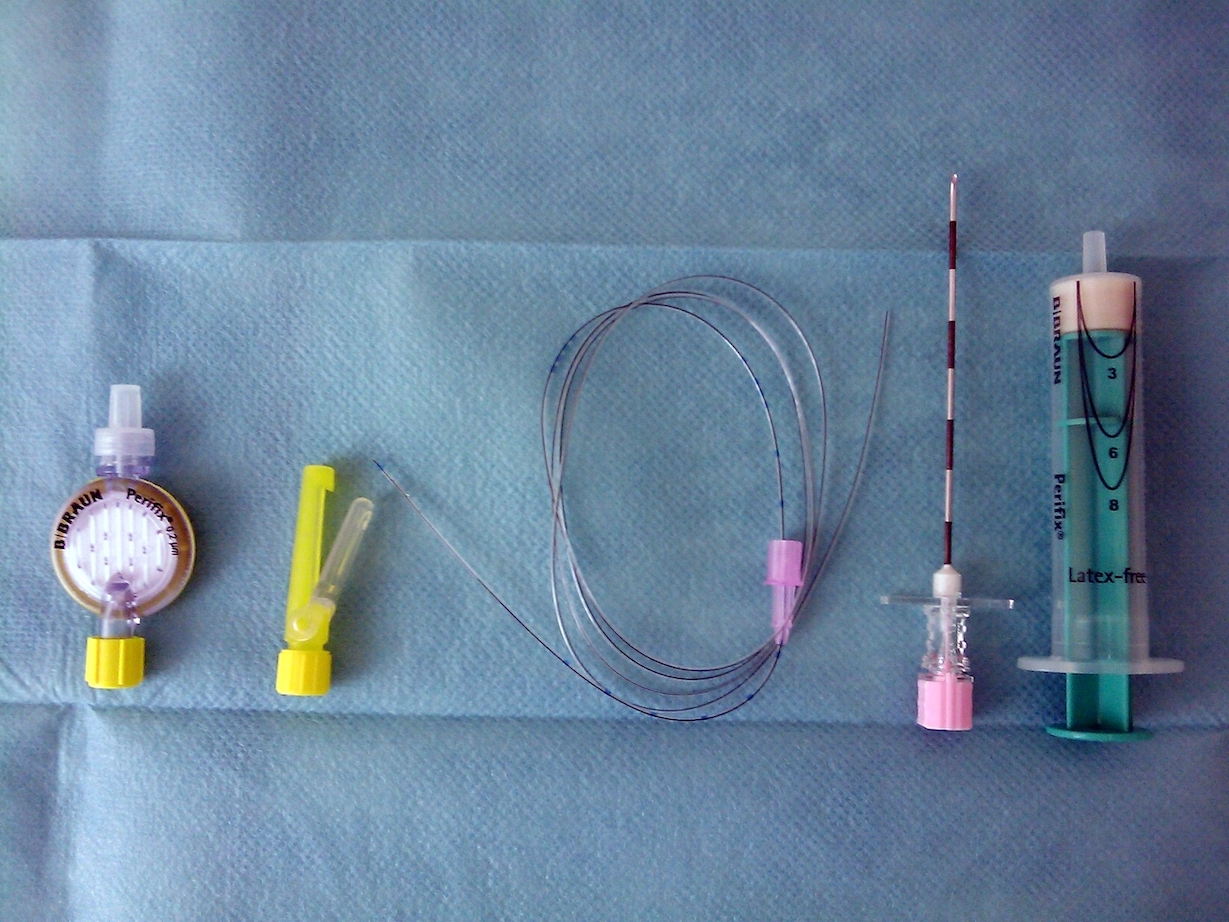

- Figure 1. Jojo. Spinal needles. License: [Public domain]

- Figure 2. Privatarchiv Foto von MrArifnajafov. Set for epidural catheterization: philter, catheter, Tuohy needle and syringe. License: [CC BY]

- Figure 3. Leila Kafshdooz et al. Epidural anesthesia. License: [CC BY]