- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Introduction

Sleep disorders are common and can present in the context of multiple medical specialities. Having an awareness of sleep disorders is useful across specialities including respiratory medicine, general practice and neurology.

This article will outline the presentation, investigations and management of four conditions affecting sleep, followed by a clinical case-based quiz to test your knowledge.

Sleep studies and diagnostic scores

The diagnosis of sleep disorders often relies on sleep studies, details of which are included in the table below.

Table 1. An overview of sleep studies.1

| Type of sleep study | Description |

| Pulse oximetry | The simplest sleep study. The patient wears an oximeter to record peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) and pulse rate overnight, usually at home. |

| Respiratory polygraphy (rPG) | Following a fitting appointment, the patient wears a pulse oximeter to measure SpO2 and pulse, straps to measure chest and abdomen movements, and a flow sensor in the nostrils overnight, usually at home. |

| Polysomnography (PSG) | A more comprehensive study that records overnight electroencephalogram (EEG), electrooculogram (EOG) and chin electromyogram (EMG) to allow staging of sleep and wake, alongside respiratory polygraphy, leg EMG and video/audio. Usually carried out in a sleep lab. |

| Multiple sleep latency testing (MSLT) | Similar to (and usually follows some) PSG studies, but without polygraphy. The patient is given multiple nap opportunities over a day in a sleep lab. |

The Epworth sleepiness scale (abridged version below) is a questionnaire developed to quantify daytime sleepiness propensity.2

It is not specific but aids the assessment and management of patients presenting with suspected sleep disorders including obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and narcolepsy.

Epworth sleepiness scale

How likely are you to doze off or fall asleep in the following situations, in comparison to feeling just tired?

0 = would never doze, 1 = slight chance of dozing, 2 = moderate chance of dozing, 3 = high chance of dozing

- Sitting and reading

- Watching television

- Sitting still in a public place (e.g. a theatre)

- As a passenger in a car for an hour without a break

- Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances allow

- Sitting and talking to someone

- Sitting quietly after lunch without having drunk alcohol

- In a car or bus while stopped for a few minutes in traffic

Interpretation of total score:

- 0-5: lower normal daytime sleepiness

- 6-10: normal daytime sleepiness

- 11-12: mild excessive daytime sleepiness

- 13-15: moderate excessive daytime sleepiness

- 16-24: severe excessive daytime sleepiness

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA)

Obstructive sleep apnoea is a condition where the upper airway frequently becomes obstructed during sleep, resulting in short periods of apnoea (not breathing).

Aetiology

Contraction of muscles in the tongue and palate hold the throat open against negative pressures during inspiration when awake. These muscles become hypotonic during sleep, particularly rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which can result in partial or complete occlusion of the airway in patients with OSA.

A complete occlusion results in a period of apnoea and usually secondary hypoxia, terminating with the patient momentarily arousing from sleep. These apnoeas can occur hundreds of times each night, resulting in highly disrupted sleep. However, the episodes are so short that the patient is usually not aware of them.

Risk factors

Risk factors for OSA include:

- Obesity

- Male sex

- Increased collar size

- Craniofacial abnormalities

- Nasal congestion

- Smoking

- Hypothyroidism

- Acromegaly

- Respiratory depressant drugs (including alcohol)

Untreated OSA is associated with diabetes mellitus and is a risk factor for hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases in later life.

Clinical features3

Typical symptoms of OSA include:

- Unrefreshing sleep

- Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS): consider assessing with the Epworth sleepiness scale and exclude other causes of EDS such as poor sleep hygiene.

- Morning headaches

- Poor memory and attention

- A feeling of choking at night

- Reduced libido

Anyone who has seen the patient sleep may report loud snoring or episodes of not breathing (witnessed apnoeas).

Typical signs to look for on examination include:

- Large body habitus, including increased neck circumference

- Narrow pharynx or nasal passages, for example, due to enlarged tonsils

- Signs of complications (e.g. pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale)

Investigations

Common investigations for OSA include:

- Pulse oximetry

- Respiratory polygraphy

Oxygen saturations from overnight pulse oximetry can be used to calculate the oxygen desaturation index (ODI, the number of oxygen desaturations during sleep per hour). This score can be used diagnostically:

- ODI < 5: normal

- 5 ≤ ODI < 15: mild OSA

- 15 ≤ ODI < 30: moderate OSA

- ODI ≥ 30: severe OSA

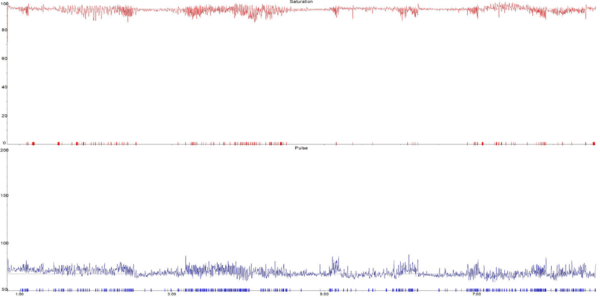

Figure 1 is an oximetry sleep study showing frequent oxygen desaturations (ODI 24/hour) in keeping with moderate obstructive sleep apnoea. The top (red) trace is oxygen saturation (SpO2%) and the bottom (blue) trace is the pulse rate. Note the close association of pulse rate variability with SpO2 dips.

Some sleep centres use respiratory polygraphy to instead calculate the apnoea-hypopnoea index (AHI). This is more sensitive and specific but can be used in a similar way to the ODI.

In some cases, if these sleep studies are inconclusive, a more complex sleep study, called a polysomnogram, may be required.

Management

Management of OSA depends on the severity and patient choice but may include:4

- Conservative/lifestyle measures: weight loss, reduce alcohol consumption, smoking cessation.

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP): positive pressure to keep the airway open, given continuously via a mask overnight.

- Mandibular advancement device: an intraoral splint worn during the night to increase airway size and reduce collapsibility.

- Adenotonsillectomy: can help children with OSA secondary to enlarged tonsils.

Insomnia

Insomnia describes being unable to sleep at night.

Aetiology

Common causes of insomnia include:6

- Primary physical conditions: for example, uncontrolled pain or frequent nocturia.

- Primary sleep disorders: narcolepsy or restless legs syndrome.

- Psychiatric causes: depression, anxiety, mania, delirium and dementia.

- Drugs: including both stimulants such as caffeine, and withdrawal from drugs of dependence such as benzodiazepines and alcohol. Several prescription drugs can disturb sleep, including steroids and dopamine agonists.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome may mimic insomnia. This syndrome occurs when the circadian rhythm is shifted back so patients cannot get to sleep until early the next day but sleep a normal amount once they are asleep.

Some patients may be diagnosed with primary insomnia when no underlying cause can be found.

Clinical features

The nature and extent of insomnia should first be established, including:

- How much sleep the patient thinks they are getting

- Whether they cannot get to sleep, cannot maintain sleep, or wake up early

It is important to take a thorough medical, drug, social and family history, in order to identify factors underlying or contributing to insomnia.

Typical symptoms of insomnia include:

- Daytime sleepiness and physical fatigue

- Poor concentration and low mood

- Other symptoms of depression, anxiety and other psychiatric conditions

- Physical pain and nocturia

Investigations

Investigations are guided by history. The patient can be asked to complete a sleep diary to track their sleep habits.

Management

Management options for insomnia include:

- Addressing the underlying cause where possible

- Good sleep hygiene, including lifestyle changes such as avoidance of caffeine and alcohol

- Cognitive behavioural therapy or counselling for psychological disorders

- Hypnotic drugs may be prescribed as a short-term solution only, and include short-acting benzodiazepines, or non-benzodiazepine hypnotics such as zopiclone and zolpidem.

- Modified release melatonin may have some benefit in older patients (over 55) with persistent insomnia.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is a rare condition in which the brain loses its normal ability to regulate the sleep-wake cycle. There are two widely recognised subtypes: type 1 and type 2.

Patients with type 1 narcolepsy experience cataplexy (conscious collapse), and have low levels of orexin in their cerebral spinal fluid (CSF).

Aetiology

Orexin (hypocretin) is a neurotransmitter involved in the regulation of sleep, wakefulness and appetite. Loss of orexin-secreting neurons in the hypothalamus results in narcolepsy. Most cases are thought to be due to autoimmunity.

There is a strong genetic associated with certain HLA-subtypes, but environmental factors may also play a role. For example, there is epidemiological evidence that influenza A infection or specific vaccinations may trigger narcolepsy.5

Clinical features

Typical symptoms of narcolepsy include:

- Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS): exclude other causes.

- Disrupted nighttime sleep and/or vivid dreams.

- Cataplexy: “conscious collapse” caused by muscle atonia, often in response to sudden emotion such as laughter or surprise; rarely seen by the clinician so diagnosis often based on the characteristic description.

- Hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations: dream-like hallucinations at the point of emerging from/entering REM sleep.

- Sleep paralysis: paralysis while awake and conscious, again at the transition between REM sleep and wakefulness.

Investigations

Common investigations for narcolepsy include:

- Polysomnography (PSG)

- Multiple sleep latency testing (MSLT)

The time it takes to fall asleep is known as sleep latency. Usually, REM sleep first occurs over an hour after falling asleep, but if REM sleep occurs within 15 minutes of sleep onset, it is known as SOREM (sleep-onset REM).

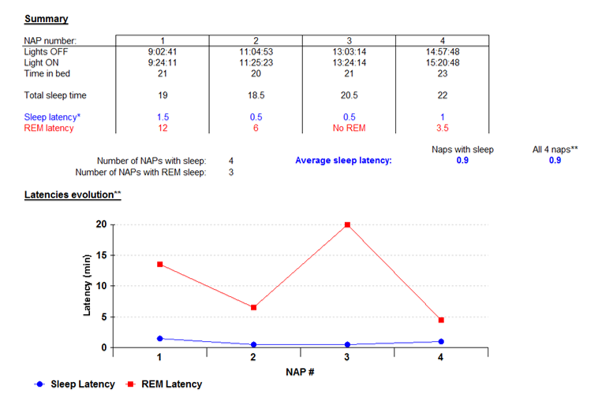

Figure 2 shows the results from MSLT in a patient with narcolepsy demonstrating a mean sleep latency of 0.9 minutes and 3 episodes of SOREM.

Other investigations that may be of use include:

- CSF orexin levels: if low/undetectable and associated with EDS suggests type 1 narcolepsy, even in the absence of cataplexy.

HLA-testing is of limited use as the allele seen in most cases of narcolepsy with cataplexy is also common in the general population.

Management

Management options for narcolepsy include:

- Good sleep hygiene: always important but rarely effective alone.

- Scheduled naps: can be helpful (brief e.g. 20 minutes).

- Central nervous system stimulants (for excessive sleepiness): modafinil first-line, dexamphetamine, methylphenidate, and pitolisant.

- Anti-depressants (for cataplexy): clomipramine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine.

- Sodium oxybate: potent sedative: improves nocturnal sleep quality, EDS, and cataplexy.

- Support: with school or work (e.g. deadline flexibility, exam extension/rest breaks, nap facilities, etc.).

Restless legs syndrome (RLS or Willis-Ekbom disease)

Restless legs syndrome is a disorder of sensorimotor processing in the brain resulting in the urge to move the legs. It is associated with abnormal sensations and often worse at night or when resting.

Aetiology

The pathophysiology is not fully understood but may involve brain iron deficiency and abnormal dopaminergic neurotransmission.7 The condition may be hereditary and tends to worsen with age.

Clinical features

Typical symptoms of restless legs syndrome include:

- Urge to move the legs, worse when sitting or lying still in the evenings

- Involuntary jerks if the legs are kept still

- Abnormal sensations in the legs (e.g. pins and needles, burning, crawling, pulling, itching or aching)

- Symptoms can be relieved by movement or sometimes if the legs are kept cool or massaged

- Secondary insomnia and fatigue

- History from bed partner may describe periodic limb movements in sleep

- Co-existent OSA (can exacerbate)

Signs to look for on examination include:

- Conjunctival pallor, angular cheilosis, koilonychia, atrophic glossitis: RLS may be a sign of iron deficiency.

- Signs of peripheral neuropathy (including from diabetes mellitus): RLS can be a complication.

- Resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia: RLS can occur with Parkinson’s disease.

Investigations

History is key but investigations that may aid the diagnosis of RLS include:

- Actigraphy: a type of sleep study monitoring limb movements.

- Polysomnography.

Management

Management options for restless legs syndrome include:

- Lifestyle changes, including sleep hygiene and reduction/avoidance of caffeine/alcohol

- Treatment of underlying cause if relevant

- Medical management may include dopamine agonists. Other medications sometimes used include L-dopa, gabapentin, pregabalin, benzodiazepines and opioids.

Other conditions affecting sleep

Idiopathic central nervous system hypersomnia is a poorly understood condition characterised by excessive day and night time sleepiness. It should be considered when no primary cause for excessive day time sleepiness can be found.

Parasomnias are a group of disorders characterised by unusual activity or experiences arising from sleep or sleep-wake transitions. This includes non-rapid eye movement (NREM) parasomnias such as sleepwalking and talking, night terrors, confusional arousal (partial awakening with confusion) and REM sleep behaviour disorder (acting out dreams), isolated sleep paralysis and hypnogogic/hypnopompic hallucinations.

Nocturnal epilepsy is caused by a frontal lobe seizure at night, typically involving screaming, frantic movements and a sensation of fear.

Further information on the classification of sleep disorders can be found in the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD).8

Case studies

Case one

A 27-year-old woman presents to her GP with difficulty falling asleep over the past month. It has been getting gradually worse, and she now estimates only around 4 hours of sleep each night. She reports feeling increasingly tired during the day and is struggling to concentrate at work. She has been told by partners in the past that she snores at night but does not report any morning headaches. On further questioning, she reveals she has been feeling low in mood since she split up with her partner around a month ago, which she feels was her fault.

She drinks two cups of coffee a day but no alcohol. She has no past medical history of note and takes no regular medications. She scores 10 on the Epworth sleepiness scale and her body mass index is 36. Physical examination is unremarkable.

She is given an oximeter for a simple overnight sleep study at home. The results give a 4% oxygen desaturation index (ODI) of 4/hour.

The most likely diagnosis is insomnia secondary to mild depression. The history includes four of the ten ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression – depressed mood, reduced energy, ideas of guilt and reduced concentration – for over 2 weeks. This is sufficient for a diagnosis of depression. Although obstructive sleep apnoea is a possibility given her large body habitus and snoring history, the ODI of less than 5 makes this diagnosis unlikely.

Management of insomnia should include addressing the underlying cause. In this case, mild depression may be treated with cognitive behavioural therapy and lifestyle changes. Many of the lifestyle changes recommended for mild depression may also help insomnia in their own right, including regular exercise, good sleep hygiene and reduction of caffeine intake.

Case two

A 14-year-old boy is referred to a neurologist after an episode of conscious collapse, diagnosed by the GP as an atonic seizure. The episode occurred while he was out with friends. He collapsed to the floor without loss of consciousness and recovered almost immediately, with no lasting confusion or weakness.

On further questioning, he reports feeling very tired during the day and frequent naps during lessons at school. However, he often has trouble getting to sleep at night. In the past, he has had two episodes of waking up and being unable to move. He has no past medical history of note and takes no regular medications.

He scores 15 on the Epworth sleepiness scale and neurological examination is unremarkable. The neurologist refers the patient for polysomnography and multiple sleep latency testing. PSG shows rapid sleep onset overnight, minor non-specific sleep fragmentation and nothing else. MSLT shows sleep being attained on all 4 nap tests. Mean sleep latency was 3.5 minutes and REM sleep was seen on 2 of the naps.

Atonic seizure is an unlikely diagnosis, given the patient did not have a post-ictal phase of delayed recovery. Narcolepsy is more likely based on the history, which includes features of excessive daytime sleepiness (confirmed by the Epworth sleepiness scale score), disrupted nighttime sleep and past episodes of sleep paralysis. The recent ‘conscious collapse’ is likely to be an episode of cataplexy.

Although this is his first episode of cataplexy, the patient suffers from excessive daytime sleepiness that may require CNS stimulants such as modafinil. If stimulants and antidepressants do not improve the symptoms of cataplexy, sodium oxybate may be considered.

Case three

A 47-year-old man is referred to the sleep clinic after his wife noticed him frequently stop breathing when asleep overnight. He has always been a loud snorer but this has been getting worse. He has been otherwise well over the past few years, although sometimes wakes with a headache that subsides over 1 or 2 hours, and has experienced progressively severe daytime sleepiness over the past few months.

He drinks 10-15 units of alcohol a week and has a 30 pack-year smoking history. He has a past medical history of type 2 diabetes, for which he takes metformin, and asthma, for which he takes an inhaled corticosteroid and salbutamol.

He scores 14 on the Epworth sleepiness scale, and his body mass index is 37. Physical examination otherwise reveals a thick neck and crowded oropharynx. He is given a home oximeter for a simple sleep study, which results in an ODI of 32/hour.

This patient gives a classical history of obstructive sleep apnoea. Risk factors include age, male gender, body habitus, alcohol intake and smoking history. The ODI confirms severe OSA.

Untreated OSA is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease. This patient already has multiple other risk factors, including alcohol intake, smoking history, obesity and diabetes.

This patient qualifies for a trial of CPAP therapy to control the OSA, thereby improving daytime sleepiness. Beneficial effects on cardiovascular risks are possible but remain unproven (beyond refractory hypertension). Lifestyle factors should also be addressed.

Key points

- Sleep disorders can present to many different specialities, so it is useful to have an awareness of problems with sleep whatever career path you choose.

- The Epworth sleepiness scale is a useful tool to quantify daytime sleepiness and differentiate it from other symptoms such as physical fatigue.

- Obstructive Sleep Apnoea (OSA) is a common presentation and should be considered in anyone presenting with daytime sleepiness, morning headaches or excessive snoring.

- Insomnia has a diverse range of causes, including both somatic (e.g. chronic pain) and psychiatric (e.g. depression) problems. Sleep hygiene should always be assessed.

- Narcolepsy is rare but must be considered in anyone describing disruption to their sleep-wake cycle, episodes of collapse without losing consciousness, sleep paralysis or dream-like hallucinations.

- Referral for a sleep study, including overnight pulse oximetry, polysomnography or multiple sleep latency testing, is often the first step in investigating problems with sleep.

Reviewer

Dr Tim Quinnell

Consultant respiratory and sleep disorders physician

Editor

Dr Chris Jefferies

References

Reference images

Figure 1 and 2 provided by the Respiratory Support and Sleep Centre at the Royal Papworth Hospital.

Reference texts

- Royal Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Sleep investigations at Royal Papworth Hospital. Available from: [LINK]

- British Lung Foundation, Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Diagnosis, Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Available from: [LINK]

- Kumar and Clark’s Clinical Medicine, 9th Edition, Respiratory Disease, p. 1085-1086.

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence CKS. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea, Scenario: Management of Sleep Apnoea. Published in 2015. Available from: [LINK]

- Dauvilliers, Y. & Barateau, L. Narcolepsy and Other Central Hypersomnias. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learning in Neurology 23, 989–1004 (2017).

- Kumar and Clark’s Clinical Medicine, 9th Edition, Psychological Medicine, p. 905

- Venkateshiah, S. B. & Ioachimescu, O. C. Restless Legs Syndrome. Critical Care Clinics 31, 459–472 (2015).

- Sateia, Michael J, International Classification of Sleep Disorders-Third Edition, CHEST, Volume 146, Issue 5, 1387 – 1394.